Christopher Rush

Father James V. Schall, one of the last great philosopher-theologians of our day, reminds us in his classic work On the Unseriousness of Human Affairs the universe is a work of art. God did not create the universe out of need. God never acts out of need. He only acts out of desire. As Love itself, God’s acts are always acts of love. The universe, man, and all else God has made were made by love. “The act of creation,” says Michelangelo in The Agony and the Ecstasy, “is an act of love.” As an act of love, a creation of desire — the universe filled no need whatever; it exists solely to be itself, to be beautiful, to reflect its maker. The universe and everything in it are works of art. “God is the only serious thing,” says Father Schall. We can relax about the rest. Now that we are calm, we can begin.

Dorothy Sayers, in The Mind of the Maker, emphasizes the Bible displays God more frequently as a craftsman than a philosopher or thinker. At the start, God is making things: speaking the universe into existence, fashioning man from dirt, reshaping the rib of man into a woman. Ideas are substantiated by the linguistic power of Jehovah Elohim. The things God makes reflect His glory, as Psalms 8 and 19 make clear. John’s gospel highlights the incarnation of the Messiah as the incarnation of thought, of reason, of language: the Word made flesh. When Paul in Ephesians calls man God’s “workmanship,” he uses the Greek word poiema: humanity is the poem of God, created to make more good poems. If everything God has made are works of art, and those works of art glorify and reflect Him, the arts are indeed the imprint of God.

We, then, are God’s poem (some of us are epic poems, some of us are limericks, but still, all poems), and poems created in the image of the Great Poet. Art is not of secondary importance. Our purpose here is not to belittle our colleagues, but let us take a moment of contemporary appraisal: how many stories do we hear of orchestras, bands, choirs, art departments shutting down or sacrificed because of tight budgets? budgets that somehow are able to fund athletic teams or purchase the latest technological “necessity” for the classroom or pursue the latest international/competitive fad STEM? True, we sometimes do hear of schools that can’t fund their sports teams, but those stories are far outnumbered by tales of the Humanities being sacrificed as ancillary or, worse, extraneous to a “real” education. Now before the engineering majors among you walk out in disgust, I am not opposed to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics or even sports. I am, though, wholly opposed to the diabolical belief they are superior to or more worthwhile or even more necessary than the Arts.

As poems created in the image of the Great Poet, we not only have a calling to support, delight, enjoy, and further the arts, we have an ontological imperative to do so. We should all be scientifically astute; we should all be mathematically savvy. We can all glorify God through the sciences, but science at its best can only tell us how. The Humanities, the Arts, tell us why: poetry, prose, drama, painting, sculpture, music, dance, acting, architecture — these are the ways humanity understands why we are the way we are, what we can do about it, what works, what fails, how we should live, not just how mechanical effects happen from mechanical causes.

But art, you say, is messy. Art is subjective. Science is objective. We are not here, remember, to posit the sciences against the arts. This is not a competition. The objection, though, of art’s messiness is still valid. Mark Twain threatens us with bodily harm if we attempt to find a meaning or moral in Huck Finn. Terry Gilliam’s film 12 Monkeys tells us even if we invented time travel, man’s pessimistic fate is inescapable. Schoenberg’s twelve-tone row is a musical pattern of constant variation without resolution, atonality rejecting outmoded notions such as melody. If this is art, how can I call this a human necessity?

Art is necessary for man as we are created in the image of the Creator — art was not necessary for God since He was complete in Himself, but man by his very created nature must imitate his creator: the poem must beget more stanzas. So art for man is necessary — it is not ancillary to politics or economics or even world peace; it is more necessary than those endeavors, as important as they may be. To be human is to be a work of art — art is a necessary component of the truly full human life. Perhaps it is time, then, to define “art.”

Art is usually considered a subjective thing. If we take the position art is subjective, no attempt at definition will get us anywhere. Even if you don’t approve of my forthcoming definition, we must establish from the beginning one essential idea: not everything can be Art. If “art” is a limitless category, no definitions will satisfy and “art” as a concept will be meaningless. Art has boundaries, boundaries I admit that imbricate, and I hereby enumerate those boundaries with the following analytical definition: art is the confluence in sensory form of aesthetics, beauty, and truth. When this ovation has died down, I shall continue.

By “sensory form” we quickly encompass the plastic arts, the visual arts, the fine arts (classic and contemporary), performance arts — all of ’em. That is the easy part. The more difficult part is now, as we say while “art” covers all these things, not every single painting, poem, movie, movement, song, or building is truly a work of art. As Dr. Schaeffer explain in his classic work we read in 12th grade Bible How Should We Then Live?, some are more akin to “anti-art.” Some poems, movies, songs (or, rather, collections of sounds or noises) are as he says “bare philosophical statements.” Not everything can be Art. A stick banging on a garbage can may be rhythmically intriguing, but it is not a song. It is not music. Art, as with everything else God is and does, has absolute, eternal unchanging standards that must be embraced and pursued. That does not mean all songs must be happy or all movies overt thematically. Ecclesiastes and Lamentations, Psalm 137 and many others belie the notion art must always be positive or sentimentally sweet. The output of Robert Mapplethorpe is not art, though. The songs of John Cage are not art. Art, real art, pursues beauty and truth through genuine aesthetic standards.

Aesthetics have fallen out of favor in Christian circles. How many great Christian American poets can you name since T.S. Eliot? How many truly good Christian movies can you name from the last 50 years? Before you say Facing the Giants or Fireproof at me, may I suggest you get a copy of The Agony and the Ecstasy starring Charlton Heston and Rex Harrison and a copy of Beckett starring Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton and see which are better movies as movies. Aesthetics deal with how successfully form and function unite and how well a thing succeeds at being what it attempts to be (such as how well a poem functions as a poem, not a bad group of sentences sloppily chopped up into little lines pretending to be a poem, for example). Aesthetics remind us a patronizingly obvious Biblical moral stuffed into a shoddily-acted, shoddily-written motion picture does not a good movie make – and it’s certainly not good art. Christians have abandoned, largely, aesthetic standards in favor of comfortable, sickly-sweet sentimental moralizing in art, music, film and just about everything else, including its sermonizing. (I am indebted to Frank Gaebelein’s The Christian, the Arts, and Truth for much of this.)

A picture of a fair-skinned Jesus smiling at a lamb is not automatically a good painting simply because of its theme. A song does not automatically become good music simply because it crams as many attributes of God as it can into three minutes of repetitive chorus. We need to be far more critical of our aesthetical responsibilities. A Christian publishing label is not enough. I don’t begrudge you your positive, encouraging music. I do reject, however, the assumption a certain label or a certain band or a litany of Bible words somehow automatically means “good music” or “good art.” They don’t. Similarly, I don’t begrudge you enjoying a Janette Oke or Francine Rivers book, but you need to know far better authors are out there. Don’t ever try to excuse your children reading bad books just because it seems Christiany — “at least they are reading” is one of the clearest signs of bad parenting. You would never excuse your children eating cotton candy for every meal with “at least they are eating,” would you? You and your children need a healthy intellectual diet as well as bodily diet. Stop settling for overly-comfortable, enervating moralistic sentimentalizing. I certainly don’t dislike sentimentality — I believe it is a much underrated component of the human experience, but good music — true artistic music — does not just evoke a chirpy smile and a momentary sense of relief.

Good music, like all good art, evokes thought, interaction, reflection; it challenges as well as enlivens; it demands we test it, it invites scrutiny. It lives up to aesthetic standards of quality. Enjoy good movies not only because they have a nice moral but also because they are good movies: engaging dialogue, believable and sincere characters, truthful events, the creation of “the illusion of an experience vivid enough to seem real.” Enjoy good songs not only because they say true facts about Jesus but also because they are good songs: trenchant lyrics, beautiful melodies and harmonies, complementary rhythmic cadences. Enjoy good books because they speak timeless truth about the human condition with vivid descriptions and well-drawn characters, regardless of culture of origin or year of publication. Christians must regain an appreciation for and adherence to aesthetics in art, or the mediocre will overtake our hearts and debilitate our minds, and those are unacceptable for image bearers of Jehovah Elohim.

From aesthetics we move slightly to beauty. In one of the best poems of all time, “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” John Keats, one of the best poets of all time, equates beauty and truth. But as Frank Gaebelein points out, they aren’t exactly the same — related but not identical.

Beauty’s connection to the arts should be obvious, but the last century has seen a drastic rejection of something so basic, beginning in the painting world then continuing in the poetic world, even in the nascent field of motion pictures. The Modernist period, with a capital “m,” from roughly 1905-1935 depending on who you talk to saw a concerted effort in the artistic world to reject the traditional standards of art and expression, substituting such outmoded bourgeois concepts as unity, objectivity, beauty, meaning, theism, and rationality for fragmentation, subjectivity, relativism, uncertainty, and non-reason. The cubist paintings of Braque and Picasso, while aesthetically skillful to be sure, fail in their presentation of beauty. They similarly fail in their presentation of truth, which will be addressed shortly. As they, and so many of their contemporaries with them, fail to create or reflect beauty, their art is secondary at best, non-art at worst.

Roger Kimball, in his thought-provoking and stomach-churning essay “The Trivialization of Outrage,” describes the present day state of affairs in art, or what passes for art in such cultured places as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. The nicest thing most of us would say about the pieces Kimball describes in his essay is “grotesque,” but the world around us clamors to call it “art,” and anyone who cannot see it as art is an uncultured backwater imbecile. In defiance of the inheritors of those who reject traditional aesthetic standards, Kimball concludes art must have “an allegiance to beauty.” If it doesn’t, the most horrific, nauseous object could have a claim to art. Reject such a thought.

If art is not subjective, are we saying beauty is likewise not subjective? We are. Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder. Beauty is an objective quality defined as all objective standards are in the person of the Great Poet, God Himself. All great strands of human experience — truth, justice, love, marriage, art, beauty, purpose, meaning — all of these and more are objectively, absolutely, eternally defined by God’s very being. Surely this is not a point of dispute for us. But, you say, what does that really mean? What is beauty? Putting it simply, beauty is the sensory and/or spiritually pleasing unity among form, function, and truth. While that may sound very similar to our understanding of aesthetics, we did mention earlier these categories imbricate. Aesthetics deals with the unity of form and function and nature: beauty adds the pleasing responses to the audience’s senses and spirit. Keats was mostly correct: beauty and truth are connected, though they are not precisely the same. Beauty appeals to the senses as well as the spirit — and if perverted, it appeals to the appetite. Truth appeals to reason and the correspondence to reality itself. Aesthetics appeal to the will and sense of order. Together, they appeal to the imago dei in humanity. When man participates in the arts — whether by creating art or appreciating art — the imprint of God is translated into the signature of man.

We proceed to the third component of art: truth. Truth’s connection to art is likewise multifaceted. Accepting, as I’m sure we do, all truth is God’s truth, regardless of the personal faith of presenter of that truth, thanks to God’s grace upon whomever He wills to dispense it, Frank Gaebelein highlights truth’s connection to art in four ways: durability, unity, integrity, and inevitability. First, truth is durable: it is unchangeable adamant, as Theodore Roethke calls it in his moving poem “The Adamant” — “Truth is never undone,” he says. We easily associate this part of truth in art with the classics: Homer, Shakespeare, Dante and the gang, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Bach, and Bono have stood the test of time. They aren’t classics because they are old; they are classics because their durability, their timelessness, is proven by their enduring truths. (Perhaps that seems circular, but we’ll let it slide for now.) The Iliad and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony may not be as overtly Christian as Handel’s Messiah and the Sistine Chapel ceiling, but their truths are undeniable and durable. Don’t be so enamored with the new you forget the great heritage of the arts. Likewise, don’t be so devoted to the classics you have no awareness of what is artistically good and true today. After all, Homer and Shakespeare were pop culture once upon a time.

Second, says Gaebelein, truth in art has unity. Unity, similar to aesthetics, is the congruence of form and structure — and why shouldn’t these hallmarks overlap? Unity requires order, a task given to man even before his fall. Gaebelein says, “In the arts, the concept or idea is given definite form; it is embodied in sound, color, or words; in wood or stone, in action or movement, as in drama or ballet. But embodiment requires unity and order, a body cannot function effectively in a state of disorganization” (89). Does this not remind us of Christ? The Word made flesh? Writers embody ideas in words; musicians embody truth in sounds; visual artists embody truth in color or motion or whatever — you bet your boots truth has unity, and products without this clearly are not worthy of being called “art.”

Third, truth in art has integrity; more than unity, truthful art has a wholeness. The work must be internally consistent: “integrity demands,” says Gaebelein, “that everything contrived merely for the sake of effect and not organically related to the purpose of the work must be ruled out” (91). True art does not have to tell the whole story from Genesis to Revelation, but it must be united and tell its story fully. Ambiguity and uncertainty are fine, but they can’t be the whole point. Reality has mystery, but it’s not an inscrutable puzzle. The conclusion need not be happy, the song does not need to end in a major key (let us not forget the artistic value of temporary dissonance), the hero does not have to survive, but true art either provides a meaningful resolution to the problems it poses or enables the attentive audience to provide it properly. If it exists solely to shock, such as the work of Robert Mapplethorpe, or solely to declare “the universe makes no sense!” like some works by Marcel Duchamp, it fails in its connection to this truth. Art can be shocking, if the audience needs to be awakened from its complacency, but genuine art does more than shock, just as genuine satire does more than ridicule: it goes the next step and explains “here’s what to do about this surprising thing that, if you had been paying attention all along like you should have been, would not have been so shocking after all.”

Last is the aspect of inevitability. True art, says Keats, feels “almost a remembrance,” as if viewing a picture or reading a poem even for the first time gives one a sense “this is how it ought to be” (92). But Gaebelein cautions us this sense may not come immediately, especially with the best art, especially if we are used to an intellectual diet of mediocrity. The best art demands long, patient attention, revisiting, and reflection. The best art, as we’ve said, can stand such scrutiny. and after we have done so, we will join the artist and say “yes, this is how it should be.” Real art has what J.B. Phillips calls “the Ring of Truth” (93). Truth is the correspondence of reality. God is Ultimate Reality, and thus the closer a work of art gets to that reality, the truer it is — the better it is as art.

Does this mean science fiction with its non-existent spaceships and time travel, fantasy with its elves and dragons, a painting of a blue tree — these can’t be art because they aren’t “real”? Of course these can be art. The “reality” we are speaking of is what the philosophers call “verisimilitude,” the appearance of being true. Much of the best science fiction addresses truths about humanity in far better ways than much generic fiction, so it’s not just a question of mimicking reality, any more than we would call Elizabethan literature false because people don’t speak that way now. A world of difference exists between a painting of a blue tree, a genuine representation of the artist’s creative expression, and a deliberate misrepresentation of reality by Jackson Pollock in an attempt to willfully reject the obvious order to reality.

While art is free to have its lesser classics (not everyone can be Shakespeare or Michelangelo), the crafters who overtly reject at least one of these principles should be understood for what they are: bad artists. At best. At worst, non-artists. Intention is a major factor in that distinction. To be truly in the discussion of art, the work and its crafter must pursue or embrace all three components. Art is a necessary human endeavor uniting aesthetic standards to the absolute values of beauty and truth.

Aesthetics without beauty, says Kimball, “degenerates into a kind of fetish or idol,” a mere mental exercise devoid of any real meaning. Beauty without aesthetic standards or truth is formless and void, likewise nothing resembling art. Truth without aesthetics or beauty sounds a lot like the clanging gongs and clattering cymbals of 1 Corinthians 13 — which, strangely enough, can be heard on most radio and television stations with great regularity today.

But what if these disagree, you ask? God created the universe and said it was good, yes? So if the universe is a work of art, why are cockroaches so ugly? Surely we aren’t saying we have to consider cockroaches beautiful? The ocean is home to many ugly, ugly fish. One person is moved to tears by a sunset, another by a Chopin concerto, another is only moved by Larry, Moe, and Curly. Don’t personal preferences play a role in what we consider beautiful? Some English majors love The Catcher in the Rye; some, rightly, think it is overrated piffle.

As time is running out, let us cut to the chase. These arguments, while worth exploring another time, are fundamentally missing the point. Beauty is not skin deep. “Good” is not up for grabs. We have no more authority to define beauty based on our personal preferences or tastes any more than we have the authority to define truth based on our personal preferences or tastes. Perhaps we don’t have to call cockroaches beautiful in the same way we don’t have to call every square inch of the Sistine Chapel beautiful. Perhaps we need to step back and take in the whole.

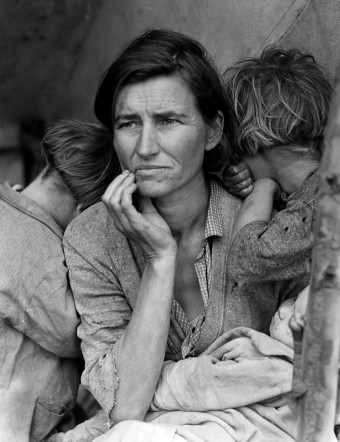

Dorothea Lange’s photographs of Depression Era poverty, surely those are art. Elie Wiesel’s Night, capturing the horror of his Holocaust experience, surely is art. I tell you what. Yes, they are. Without leaning into the relativism we have been avoiding all night, beauty is more than just prettiness. Truth is more than just fact. Aesthetics are more than “things I like.” Homer never mentions Jesus, and yet his work conveys truth about the futility of seeking one’s own glory at the expense of others and the beauty of sacrificing oneself for loved ones far better than most sermons you or I will ever hear. Art is necessary for the full, rich human life.

For centuries, critics have been waging a war whether art is a mirror or a lamp: a reflection of the times or a guide to where humanity should go (or is already going). For Christians, the choice is clear: without trying to sound like a fence rider, good art is indeed both. Art reflects mankind truthfully, as he is and as he was and as he should and will be. Art points man back to where he came from and where he belongs. Art points man back to the Creator. Art is the imprint of God. Art done properly is the signature of man, displaying the image of God within. Through the arts man leaves his best testimony to the future of humanity what he has learned from his past and his present. Through the arts man best worships and imitates God Himself. As Gaebelein sums up, “we cannot downgrade the arts as side issues to the serious business of life and service as some Christians do” — a seriousness we take too seriously, as Father Schall so wonderfully reminds us. Returning to Gaebelein: “When we make and enjoy the arts, in faithful stewardship and integrity, they can reflect something of God’s own beauty and glory. Through them we can celebrate and glorify the God ‘in whom we live, and move, and have our being’” (97).

Works Cited

Gaebelein, Frank E. The Christian The Arts, And Truth: Regaining The Vision Of Greatness. Portland: Multnomah Press. 1985. Print. All works cited except those listed here were mentioned by Gaebelein in his work and thus taken from him.

Kimball, Roger. “The Trivialization of Outrage.” Experiments Against Reality: The Fate of Culture in the Postmodern Age. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. 2000. Print.

Schall, Father James V. On the Unseriousness of Human Affairs: Teaching, Writing, Playing, Believing, Lecturing, Philosophizing, Singing, Dancing. Wilmington: ISI Books. 2001. Print.