Garrett Fields and Michaela Seaton Romero

“Ode to the West Wind” Analysis

Garrett Fields

The poem written by Percy Shelley, “Ode to the West Wind,” personifies the winds in the west. It is seen as a powerful force that destroys but also preserves. It kills the decaying and weak to make a path for the new. It destroys the old and provides a new environment for the new.

In the first stanza, Shelley says the West Wind is “wild.” It blows away the leaves that have died and started to rot. It makes way for the springtime after the rough winter. The wind takes the seeds off the trees and bushes and buries them in the soil so they can spring up into new life a few months later. The seeds bloom into new life during the spring. It destroys the old and starts a new fresh beginning in the spring. This is why the west wind is described as both a destroyer then a creator, or a preserver.

In the next stanza, Shelley talks about the sky. He talks about the effect of the winds on the clouds. The winds break the clouds apart almost like the decaying leaves of a tree. The clouds become rainclouds and look ominous over the earth. The clouds are compared to the outspread hair covering the sky from the horizon to its zenith. The craziness of the sky is compared to Maenad, worshipper of the Greek god of wine. Shelley uses this comparison because Maenad worships the god in a sort of wild and crazy way, lifting her hair like tangled clouds. These indicate an approaching storm.

The West Wind then becomes a funeral song. It is being sung because the year is dying. The dark night sky becomes a grave or a tomb where the clouds mold the tomb. They will soon pour down rain.

In the third stanza, the West Wind blows across the Mediterranean Sea. He describes it as a vast sleepy snake, which dreams of old civilizations rich in flowers and vegetation. In the sea’s sleep, it sees “old palaces and towers,” which quiver when the wind blows. The West Wind also affects the Atlantic Ocean. The plants under the surface tremble at the sounds of the strong breezes. They fear the power of the West Wind.

In stanza four, the West Wind becomes a more personal force. Shelley said if he were one of the leaves, or the clouds or waves, he would be able to feel the power of the West Wind. He said during his childhood he had the power and speed of the West Wind. Shelley said he no longer has the strength and speed like he did in his childhood. The burdens of life have dragged them down. He is facing problems in his life, which have drained his strength. He now looks to the West Wind for help.

In the last stanza, Shelley offers himself to the West Wind in the same way as the leaves, clouds, and waves do. He wants the wind to be a musician, and he should be used as a lyre for this purpose. The music could be gloomy but a sweet sound. Then he compares himself to a burning fire with sparks and ashes. He requests the West Wind blows his sparks and ashes among mankind.

Shelley ends his poem with the hope the West Wind will take his words across the world. Winter is a symbol of death and decay, but spring brings new life and hope. He portrays this poem as saying if there is despair and pain now, then hope and optimism are just around the corner. If winter is here, spring isn’t far behind.

“Ode on a Grecian Urn” Analysis

Michaela Seaton

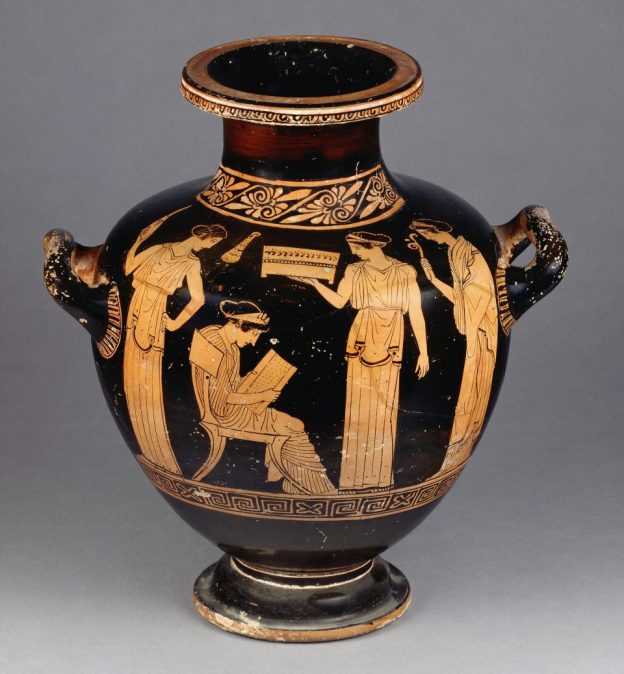

“Ode on a Grecian Urn” is a great example of Romantic poems. It is a highly emotional poem addressing things not present. Written by John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn” utilizes moving language, sensations, and images to get its point across. The main theme is constancy or eternity, the innocence that comes with not changing.

In the first line of the first stanza, he says “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness” which literally means pure bride of quietness. It isn’t actually talking about the marital vows of an urn, it is talking about how the urn is silent; she’s not an “adulterer” to quietness, literally meaning the urn was adopted by silence and slow time. She keeps all her secrets, while still showing the story upon her. The second line is similar in its message: “Thou foster child of silence and slow time.” Once again, Keats uses imagery to show how he sees the urn, as a perfect representation of stagnant time.

The next two lines, “Sylvan historian, who canst thus express/A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:,” talk about the urn’s job as a historian. Keats compares her job to his job as a poet. She uses pictures to tell her tale, while he uses words and rhymes. In his opinion, her way of telling the story is superior.

The next three lines are the first close look at the urn: “What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape / Of deities or mortals, or of both,? In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?” This is talking about the actual artistic qualities of the urn. Apparently, it is ringed with leaves, perhaps contains shapes of gods and men frolicking about in different areas of nature and life.

“What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? / What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? / What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?” These next three lines pose questions about the urn, asking what it is revealing about history, what stories is it telling. Keats is telling the readers what is coming up.

Then comes the next stanza. In the first two lines Keats says “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;” In this stanza, it appears he has turned the urn so one of the scenes is showing, a scene with flutes. When he says the unheard melodies are sweeter than the heard, he is probably talking about how with the scene pictured on the urn, the music and fun you imagine is happening is perfect, while in real life often expectations are not reality. Those people on the urn are actually living, in his mind, but simply frozen in time.

Lines 3-4 say “Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d / Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone.” In these lines, Keats is ordering the pipes to play to his imagination, which ties in with the previous lines. In his imagination, any scenario he creates will be perfect in his mind. The melodies have no tunes in the real world, but in the imaginary world they are the perfect notes.

The next two lines say “Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave / Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;” In this, the youth is in an eternal spring beneath a tree that will never lose its leaves. He is stuck in the same position, playing the same song but never being able to change. For Keats, however, this is preferable. The youth never has to experience the pain of passing time.

The next four lines say “Bold lover, never, never canst thou kiss / Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve / She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss / For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!” This scene seems to be referencing a young man chasing a maiden. This is probably what Keats was talking about earlier, with “mad pursuit.” In this scene, the man is ever chasing the maiden, but Keats tells him not to despair. Keats knows because they are frozen in time on the urn, he will never stop chasing the girl, and the girl will never lose her beauty. It’s much different in the world where time marches on.

The third stanza begins with “Ah, happy, happy boughs! That cannot shed / Your leaves, nor ever bid the spring adieu.” Again, there is an almost Norman Rockwell feeling to the urn; it’s like what an ancient Greek version would look like. The tree is stuck in perpetual spring. Never will it lose its leaves. Keats obviously thinks this is a good state to be in, never will the tree have to suffer through a winter.

“And, happy melodist, unwearied / For ever piping songs for ever new / More happy love! More happy, happy Love!” are the next three lines. Once again, Keats is showing how happy he considers the scenes on the urn to be. This melodist is playing a song that will never go out of style, with a pipe that will never break. He is, and always will be, happy. Keats envies him, and he calls for more happy love songs; he wants to feel what he imagines it would be like, a perfect happiness that never ends because time cannot touch it.

The next two lines state “For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d / For ever panting, and for ever young”. This line seems to be talking about the birds and the bees. Joy that man and woman can experience on the urn for ever and ever and never tires. The next three lines also talk about this passion, but in the real world. They say “All breathing human passion far above / That leaves a heart high sorrowful and cloy’d / A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.” In this one, Keats seems to be saying the people in the world “above,” those who are looking down on this urn, they, too, experience passion, but it ends. Once the deed is done, it is over, and on comes the regret. A fever, a dry mouth, a muddled brain are left behind, a stark contrast to the moment of happiness. To Keats, the people on the urn, the men or gods chasing the maidens, are still in the moment of happiness. They aren’t regretting any decisions right now, and they never will because for them time does not exist.

This is where stanza four begins with the line “Who are these coming to the sacrifice?” Keats has turned his attention off the scene of the lovers and onto one where a sacrifice is about to take place. He wonders who is coming to watch it happen. Lines 2-4 give a better picture of what is happening. “To what green altar, O mysterious priest / Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies / And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?” He asks the priest where he is taking the bellowing cow, but the priest will never reach the green altar because they are all frozen in time. The heifer is outfitted with flowers, so she is probably destined for the gods as a holy sacrifice.

The next three lines say “What little town by the river or sea shore / Or mountain built with peaceful citadel / Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?” The priest and cow have a following, a crowd coming with them to the altar. Keats imagines what their little village would look like, desolate with all its people gone to worship their gods. However, the town could be by a river, or a sea shore, or on a mountain; so the town is not pictured on the urn since we do not know what it looks like.

The last three lines state “And, little town, thy streets for evermore / Will silent be; and not a soul to tell / Why thou art desolate, can e’er return.” In these, he address the sad state the town is left in for eternity. It will be forever empty, its people will never return. Although most of his words have been happy, yearning for a stop in time, these seem sad. He feels sorry for the village, whose people are gone and never coming back.

In the fifth stanza, he begins with “O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede / Of marble men and maidens overwrought / With forest branches and the trodden weed.” In these, he both praises and dismisses it. At first, he marvels at its shape and fairness. But then he seems to think it too ornate, too fancy. There are too many branches, the details are too well done, like it looks alive. It almost sounds as if Keats is jealous of it, because the pictures it displays show what he cannot have: eternal happiness.

“Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought / As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!” say the next two lines. He seems to be accusing the urn of teasing him into thoughts about eternity, like one would tease a knot out of a ball of string. Keats does not like what he is thinking about eternity. The eternity shown on the urn is not the eternity that we live in. There, there is constant happiness and joy, while we must suffer here.

The next three lines state “When old age shall this generation waste / Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe / Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st”. Keats imagines even after everyone in his generation has died, this urn will still be around. The problems of the current generation will be no more, but the new generation will have different ones. Even still, the urn will stay the same. In fact, it gives the same advice to every generation.

The advice is in the last two lines of the poem, which say “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” He is not saying simple truth and beauty are the same. He is saying beauty, what is the meaning to our lives, is the same as truth, which is the meaning for our being here. These thoughts can be had while looking at the urn, thoughts of life, regrets, and eternity. No matter what generation looks upon it, they are all going to see that, feel what Keats felt. To him, you don’t need to know the truth of the history books, or the celebrities, or the medical magazines, you simply don’t need the truths that are passed down from generation to generation.

I enjoyed “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Although I certainly did not agree with its suggestion that we throw out the truths of the past, I do understand his longing to live in a moment in time that is always happy. Those happy people on the urn represent what I’ll never have until Heaven: eternal bliss. But at least I am assured in my eternity; Keats is not so lucky.

“Ode on a Grecian Urn” addresses much deeper issues than can be seen on first glance. Questioning truth, examining eternity, and wondering about beauty are often not seen in poets of today. Keats throws out what had been taught in previous generations and focuses on the one thing he believes to be constant: beauty.