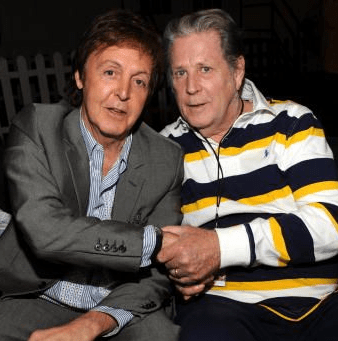

Peter Runey, Dylan Fields, Noah Eskew, and Melissa Yeh

Peter Runey’s Critical Listening Top 10

1. “Nobody Loves You (When You’re Down and Out)” by John Lennon

2. “Come Together” by The Beatles

3. “A Hard Day’s Night” by The Beatles

4. “Get Back” (Live on the Rooftop) by The Beatles

5. “Don’t Let Me Down” by The Beatles

6. “Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight” by The Beatles

7. “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys

8. “Band on the Run” by Paul McCartney(/Wings)

9. “The Long And Winding Road” by The Beatles

10. “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds” by The Beatles

This was extremely difficult to boil down to the top ten, however these are my thought-through, most profound songs of the Critical Listening class this year. While many of these carry real-life meaning to me since they’re attached to a fond memory of mine, some of these I admire purely based on their musical and lyrical quality.

“Nobody Loves You (When You’re Down and Out)” — John Lennon creates one of the most uniquely-sounding songs I’ve heard from him, whether it be from his solo career or from the Beatles. He incorporates a string orchestra as well as trumpets/horns, all the while still retaining the same classic Lennon vibe from the Beatles so many loved. Lyrically, Lennon takes a creative approach to exposing the fact people tend to only show love when they want it in return (“I’ll scratch your back and you scratch mine”), as well as the fact often great people are only admired and recognized for their accomplishments when they’re “six feet in the ground.” Ironically, Lennon gained even more of a following of his ideas upon his assassination.

“Come Together” — Despite the fact Lennon is known to be involved with the use of psychedelics, few can say the Beatles’ music became any less unique when they began using. Lennon crafts an incredibly artistic song beginning with a deep bass masking whispers of “shoot me, shoot me,” most likely referring to heroine. At this point, John Lennon was becoming a figure in many a cultural and even political scene (as an influencer not a participant) and used the song as somewhat of an anthem for the freedom to use psychedelics. Despite its intentions, I find this song to be one of the most creative and catchy songs the Beatles ever produced.

“A Hard Day’s Night” — I could tell an incredibly long story of a memory attached to this song for me. Instead, I’ll just say this song became very relevant to me on one special night in the Shenandoah mountains.

“Get Back” (live on the rooftop) — This song mostly holds its meaning to me since it was the final song to be performed live by the Beatles. I found it amusing that their desire was to be dragged off the venue by police since the concert was considered to be an unannounced public interruption, however the concert ended with a mere “pull of the plug,” so to speak, from the local authorities. It’s not just a special song but also a special performance since it was the last time the four ever played together in public.

“Don’t Let Me Down” — There are a few reasons why I love this song. The first of these is this was also played at the final rooftop concert. Another reason is Paul and John both harmonize beautifully in this song, which makes John’s raw, heartfelt message of love to Yoko Ono that much more special.

“Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight” — While these are technically two separate songs, the track was ordered so “Golden Slumbers” could carry seamlessly into “Carry That Weight” as part of a 6-part climactic medley in Abbey Road. I love “Golden Slumbers” because it begins simply with Paul and a piano playing a sheet of music he found on his grandfather’s piano with his own words put to it.

“Good Vibrations” — While this is the only Beach Boys song that made the list, it’s definitely one of the most enjoyable listens of the years. I appreciate the upbeat rhythm and lighthearted melody. The Beach Boys have mastered the art of crafting songs perfect for driving in a car with the windows down on a summer day, and this is certainly one of those.

“Band On The Run” — Paul branched out with this song. He begins to step out of his shell of his creativity since he no longer experiences the same pressures of being in the Beatles now that he was in control of his own solo career. On this track, Paul, in a way, mixes three songs into one, making a roller coaster of a song, but not to the point where it’s distracting to the listener. Paul’s musical brilliance really shines when somehow he pulls off a silky-smooth transition from the magnificent blare of brass and electric guitar instruments into an acoustic guitar/drum combination for the rest of the track.

“The Long And Winding Road” — This is easily one of the most emotional song from the Beatles, aside from maybe “Blackbird.” Paul takes the listener on a journey down a long and winding road with this song but leaves the listener with little conclusion or sense of achievement. It’s inferred that the end can’t be reached, and it’s unattainable. Obviously, this is how Paul must’ve felt at some point in his life, and he depicts this season of life very effectively and eloquently.

“Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds” — This song is believed to be a reference to a drug known as LSD, which was likely being used by at least one of the band at the time. One thing I do appreciate about the times when the Beatles were under the effects of drug usage is their creative thinking tended to be much more outside the box, which resulted in unique tracks like “Lucy In the Sky.” The song doesn’t make much sense, lyrically, but to me it doesn’t have to in order to appreciate its special sound.

Dylan Fields’s Critical Listening Top 10

1. “A Hard Day’s Night” — Beatles

2. “Come Together” — Beatles

3. “Little Deuce Coupe” — Beach Boys

4. “Don’t Let Me Down” — Beatles

5. “Maybe I’m Amazed” — Paul McCartney

6. “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” — Beach Boys

7. “All Things Must Pass” — George Harrison

8. “Help Me Rhonda” — Beach Boys

9. “Pease Please Me” — Beatles

10. “The Monster Mash” (Live) — Beach Boys

This list was a whole lot harder to make than I anticipated it being. Many of these songs may not be my favorite for their musical aspects but the stories behind them. I will be explaining why each song is special to me throughout the course of this paper.

“A Hard Day’s Night” — This is the epitome of Critical Listening music for me. It may not be my favorite critical song musically but the story behind it makes it what it is to me. In the beginning of the year when Critical Listening was just starting, we had just heard this song and Pete and I were jamming to it non-stop. We literally had this album on repeat every time we were in the car. That being said one day I had the bright idea to go on a road trip/camping trip to the Shenandoah mountains with Pete and Pedro. The trip started off great: we were having a ton of fun and everything was going great. We arrived in the mountains and that’s where things started going wrong. There was a police car involved and we had to stay in an overpriced dirty motel instead of camping out. We got to camp out the second night and it was decently fine from then on out. So fast forward to the ride home, Pete throws on this song and it just made sense. That trip was “A Hard Day’s Night.” So every time I hear this song I think about this trip, the bad parts but mostly the good.

“Come Together” — This song has been one of my favorite Beatles songs since the start of the class. I love the intro of this song. I think the crazy thing about the beginning and throughout the song is John is saying “shoot me” and ends up getting shot and killed; he obviously want talking about guns in the song but it is still ironic. I am going to say this for a lot of these songs and I could probably say this for all of them but this was a song me and Pete loved to jam to in the car.

“Little Deuce Coupe” — I really don’t like this song musically, but the story behind it is what makes it one of my favorite Critical Listening songs. One of the first times we were listening to this song in first semester I think it was Pete that started singing the chorus obnoxiously at a super high pitch, then I would sing low, then Noah would go high with Pete. This turned into a thing we did. We would just sing “Little Deuce Coupe” as obnoxiously as we could. We did it everywhere, in the classroom, in the halls, in the parking lot, everywhere.

“Don’t Let Me Down” — My first memory of this song was the video of them playing on the roof around the time they were breaking up and all the people come out of their houses to watch. After we watched that in class I had it stuck in my head and I was jamming to it non-stop and apparently Pete did too because I was texting him one night and I said I was jamming out to the Beatles and he said he was, too, and I texted him “Don’t Let Me Down” was a banger and as I hit the send button I got a text from him saying basically the same thing. We always kinda joked about that.

“Maybe I’m Amazed” — My words while listing to this song for the first time were “Dang, I like this song … Oh, dang, I really like this song!” This song was one of those rare cases of love at first hearing of a song; most songs take me a couple times to listen to them to really like them. This one was not the case; I had this song stuck in my head for about a whole month after I listened to it one time. I remember jamming to this with Pete while going from thrift shop to thrift shop looking for pianos to cure our addiction to music.

“Wouldn’t it Be Nice” — Every time I hear this song I see Joanna and Sarah on stage at the Battle Cry talent show. This song makes me think of my class and all the memories we shared together. It’s crazy how music will do that to you.

“All Things Must Pass” — This has been my theme song for the past couple of weeks with so much changing. I am going from one huge part of my life to the rest of my life. This is the end of the beginning for me and I can really relate to this song right now. I loved high school and made so many memories here but like everything in life all things must pass, good things or bad they all will pass.

“Help Me Rhonda” — I don’t really have a story behind why I like this song, but this could easily be my favorite Beach Boys song. It’s just so free spirited and groovy and I dig that. This is in my top ten in any genre for jam out sessions in the car.

“Please Please Me” — This was my first song in Critical Listening I really liked. I listened to this song and the entire album a whole lot at the beginning of the class. I still really like this song and it brings me back to Noah, Pete, and me dancing all around room 103 all first semester.

“The Monster Mash” (Live) — I don’t like this song for its musical sense unless it’s around Halloween, but this song was a classic in the first semester of Critical Listening. Noah and I would sing this obnoxiously all the time and it was so much fun. I remember sitting in our second period study all just doing our math homework and singing “He did the mash … He did the monster mash! … It was a graveyard smash.” That song was just a lot of fun to me.

In conclusion, I loved this class and I’ve said it before but I’ll go ahead and put in in writing, this was my favorite and most beneficial class I ever took at Summit. Not to take anything away from the other classes or teachers, but this class had such an impact not only in my taste for music but it really did impact my life. It brought Noah, Pete, and me closer, and they are some of my best friends I have. It also made me open my eyes to music: I discovered so much more music and even made me want to get in the realm of creating music, which I was not successful in at all. It also played a huge roll in choosing my thesis topic because music was constantly on my mind during that time. Mr. Rush, thank you for offering this class and putting up with us even when I was rolling around on the cart or playing with the music stand; I truly appreciated this class.

Noah Eskew’s Favorite Five, yea Six Beatles Albums

What are the top 5 Beatles records? I would put that question in a top 5 list of unanswerable questions. However, I have determined my 6 favorite Beatles records based on the ratio of songs that left a memorable and positive impression on me over the total number of tracks on the LP. The one fault to this method is it doesn’t account for how much I enjoy a specific track; it instead simplifies it to: Did I like it? For example, I thoroughly appreciate the songs “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “For You Blue,” “Across the Universe,” and “Get Back,” which are all featured on Let It Be, but the rest of the album leaves much to be desired. The outcome of this process slightly surprised me (in regards to the resulting order), even though my previous general idea was almost precise.

#5 A Hard Day’s Night

With this album I found seven of the thirteen songs appealed to me. The title track begins with a special strum of a chord. To this day, few can identify what note is exactly being played. The lyrics are highly relatable to anybody who’s been hard at work. Plus, the guitar solo is swung in a manner that’ll make the guitar player and the average listener happy. In this song, the Beatles prove within the context of pop sensibility they can remain true to their musicianship. “I Should Have Known Better,” “If I Fell,” and “I’m Happy Just to Dance with You” also add to what is truly a solid start to this album. “Can’t Buy Me Love” is practically a Beatles staple. With a catchy chorus, and rather true lyrics in the verse, this hit did not disappoint. Lastly, my favorite song of the entire work is without question “You Can’t Do That.” With a jangly guitar intro, John’s impeccable attitude-filled vocals, and Ringo’s driving drum and cowbell groove, this song has placed itself among my favorites.

#4 Magical Mystery Tour

There are seven songs of the twelve on this compilation of which I am fond. The title track kicks off the record with a catchy repeatable chorus, and in between choruses we get a glimpse of the mysteriousness to be experienced in the following minutes of the LP. “Your Mother Should Know” is yet another classic involving Paul and the piano. The piano riff bounces along lightheartedly, while the lyrics are a fun alternative to some of the other strange styles during this period. The hits that have emerged from this compilation included such smashes as “Hello, Goodbye,” “I Am the Walrus,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” and “All You Need is Love.” Part of the genius behind the Beatles’ discography is their ability to churn out the hits with fun and catchy choruses, but simultaneously the ability to entertain with more eerie sounding progressions as well.

#3 The Beatles (The White Album)

Out of the 30 tracks produced on this double album, I like listening to 18 of them. If I always had the time required, I would not skip any of the first 12 tracks (except maybe “Wild Honey Pie”). The first dozen on disc 1 could be an album by themselves. This, above all the other albums, shows the individual musical personality of each of the four Beatles. This is probably due to the fact the group did not spend much time together in the studio compared to previous sessions. Paul thrives on “Back in the USSR” (the driving rock ‘n’ roll tune), “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” (the happy and hopeful pop song), “Martha My Dear,” “Birthday,” and “Helter Skelter.” George offers some of my favorite Beatles numbers of all time such as “Savoy Truffle,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” and “Piggies.” John ventures into interesting lyrical processes by incorporating the stories of other Beatle songs into the phrases of “Glass Onion.”

#2 Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Many magazines and other award-givers rank this work as the greatest album of all time. Combining the sounds of the psychedelic rock movement with those magical Beatle melodies, the Fab Four did indeed produce one of the most revolutionary records ever. Eight of the songs stick with me years after hearing them. Tracks one through five have the flow of a live performance. “Fixing a Hole,” “Getting Better,” and the reprise of the title tracks remain my favorites for their interesting lyrics, simple but solid guitar parts, and energy that really speaks to me.

#1 Tie Between: Revolver & Rubber Soul

Within these two records begins the change of the Beatles’ career. They move from the lovable mop-tops into the genius musicians that have pulled themselves out of live performances in order to further their art. They begin to incorporate eastern influences into their songs, but yet again don’t shy away from their rock ‘n’ roll identity. Each of these albums included 14 tracks, and each of the albums included 9 tracks that I love. “Nowhere Man,” “Think For Yourself,” “What Goes On,” and “I’m Looking Through You” are my favorites from Rubber Soul. “Taxman,” “I’m Only Sleeping,” “She Said She Said,” “Good Day Sunshine,” and “Got to Get You Into My Life” are my favorites from Revolver.

Melissa Yeh on “Band on the Run”

With the Wings album, Paul McCartney released “Band on the Run” in 1973. The song has different interpretations based on history and listeners agree it is well composed and one of his most memorable. The most popular and speculated-on theory from this song concerns the reflections and aftermath of the breakup the Beatles underwent from Paul McCartney’s perspective. He confirms in an interview the song was influenced by one of the many long meetings where George Harrison remarks on the regrets of the events going on at the time. “If I ever get out of here, thought of giving it all away, to a registered charity.” For this phrase especially, he wishes they could have spent more time on the music, focusing on the good, and the wealth was not worth that happiness; instead it should have been devoted to charities. The song then develops his freedom from the tension of the break-up and his ability to pursue what he wants to without being burdened by the obligations the band held over him. When asked about if the song was in association to the break-up, Paul McCartney responds, “Sort of, yeah. I think most bands are on the run.” In another comment, one listener feels the song is not as much about the break-up as people think the song is. In fact, it’s completely absurd and almost obsessive to relate everything back to the Beatles. In another part of the song, articles and listeners have alluded to the line “and the jailer man and sailor Sam were searching everyone,” being connected to the incident in Sweden in 1972. Paul McCartney and all of group Wings were arrested on drug charges. Thus, the police were searching them at the time. Later comments express McCartney’s plead for focus away from these types of charges and on what matters most, the music. Overall, the song is about a prison escape and the shift from captivity to freedom. “Stuck inside these four walls, sent inside forever,” describe the jailed prisoner, cut off from the outside world. Again the prison is referred to in “if I ever get out of here.” The explosion symbolizes the escape and again the band is running from police, “in the town they’re searching for us everywhere, but we never will be found.”

When talking about the instrumental in working with the theme of that escaped prisoner, the composition itself embodies the mood of the song. Paul McCartney has been noted for his ability to combine multiple songs into one; here there are three distinct melodies. The first transitions into the second from verse one to two, beginning at, “if I ever get out of here.” The tempo speeds up slightly and moves into a minor key through an instrumental break. This represents a sense of sadness and regret in the tone of the song. The third begins after the dramatic instrumental charge into the verse, “Well, the rain exploded with a mighty crash as we fell into the sun.” The song modulates from A minor into C major, now with a new and happier tone from what it was before. The movement of the song captures that feeling of relief and freedom.

What moved me to choose this song followed from the moment where as I was sitting in class, I heard the first chord and immediately decided I like this song. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed the music in class, but none of the songs had caught my attention as quickly as this one. While in the bus in Germany passing through the countryside, I remember going through a tunnel or under a bridge and right as the song changed from the second part into the third, the bus flew into the open again into the light with long fields surrounding us. That moment McCartney creates of an explosion into freedom was more than what I can describe in words. With that, this song will always tie me back to the memory with our class, driving past landscapes in Europe.

Bonus Track: Mr. Rush’s 5 Mandatory Beach Boys Non-canonical Albums for Real Fans

1967: Sunshine Tomorrow — Wild Honey is one of my favorite BB albums, and this 2017 release of many WH outtakes, alternate versions, and unreleased live cuts, including the entire Lei’d in Hawaii album, make this essential. As if that wasn’t enough, it has Smiley Smile outtakes and a beautiful a cappella version of my favorite BB song, “Surfer Girl.” Don’t miss this.

Endless Harmony Soundtrack — This collection of rare cuts accompanying the biopic is a monumental gift. You’ll get a fresh look at a band you think you know, a fresh look that will only reinforce your love for them.

Hawthorne, CA — Thanks to the success of Endless Harmony, Capitol Records continued to open the vaults of rare cuts, radio spots, demos, and more. Just when you thought you heard it all, you learn you haven’t heard anything yet. It’s disjointed at times, but it is more BB tracks, which is what we want.

Made in California 1962-2012 — This 6-cd panoply of the band’s career is pricey but worth it. It has a lot of rare live tracks, alternate versions, and much forgotten work from Carl and Dennis. If you’re a real fan, you need this mega-set.

Ultimate Christmas — Not only does this have the entire original Christmas Album, it collects all the tracks for the unreleased second Christmas album plus all the rare promos, singles, and other Christmas goodies. It’s a must-have.

*2023 Editor Note: Be sure to get the original version of Ultimate Christmas! The recent streaming versions delete the best song on the collection, “Christmastime is Here Again.”