Lia Waugh Powell

Abstract

To determine whether word repetition or using semantically elaborated sentences is better for memorization, participants were randomly exposed to words presented in either of those two conditions. There was a total of 165 participants. The experiment was conducted online through the Online Psychological Laboratory. Participants were randomly assigned to hear 15 words used in either semantically elaborated sentences, or the words were repeated to them several times. There were line-drawn symbols also presented with each word as a visual aide. Upon completion of the experiment, participants were asked to retrieve as many words as possible through three tasks: free recall, cued recall, and recognition. The results of the experiment were measured using an independent samples t-test. There was no significant difference found in the free recall portion of the experiment between the two conditions. However, there was a significant difference discovered in the cued recall and recognition portion of the exam when comparing both conditions. These results support previous research regarding the importance of the relationship between elaboration and memorization.

Line-Drawn Symbols and Words

Background Research

Discovering new and efficient ways for children to learn has been of interest for both psychologists and educators for years. Learning how children’s brains process information is the key to understanding this task. One of the first important milestones in a child’s life is learning how to read. According to Lee (2016), as parents or educators begin to teach this skill, it is common to use children books that both incorporate a picture of something (an animal or an object) and a single word used to identify the picture below it. As the book is read to the child, the educator often points to the picture and repeats the words that identifies what the picture is. The goal of this exercise is to teach the child to memorize “sight words,” so they do not have to sound out a word, but rather can see it and recall what it says immediately. However, one may wonder what the most effective method to help others memorize words may be. There is the traditional method explained above, where a line-drawn symbol is shown and the word is repeated. Another method is to associate each line-drawn symbol with semantically-elaborated sentences. Semantically-elaborated sentences in this experiment are sentences that give the specified word meaning by linking it to an image or a related idea (Benson, 2003). But is there a difference in memory between those who memorize using word repetition and those who memorize using semantic elaboration? To further evaluate which method is more effective, this study will explore the differences between each technique.

Meltzer and colleagues (2015) conducted an experiment to gain more understanding of the relationship of perceptual short-term memory and semantic mechanisms that led to converting from short-term memory to long-term memory. The authors hypothesized short-term repetition of words under articulatory suppression would lead to higher levels of recalling sentences. Articulatory suppression is the effort to hinder memorization by giving a task to the participant. In this experiment, the task was to either tap fingers in between the words being presented to them, or to count backwards by three. Ultimately it was hypothesized there would be less forgetting when the words were presented in sentences, and the semantically-based sentences would allow encoding within long-term memory.

Twenty local university students participated in their study, with the average age of 21.9. Two tasks were required for the experiment. When the experiment began, the participants were alone in a room and used a computer to be presented audio sentences. The sentences presented to each student were either high in levels of semantic concreteness, or abstract. According to Meltzer and colleagues (2015), sentences high in levels of semantic concreteness contain rich pictorial imagery. In contrast, abstract sentences did not contain sensory information. The first task consisted of the students listening to sentences. After the sentences were heard, the students experienced a 14-second delay. During the delay the students were randomly assigned to either tap their fingers or count backwards by three. After the 14 seconds concluded, the students were asked to repeat the sentence verbatim. For the second task, the sentences were presented again, but the two main words (the subject and verb within the sentence) were visually shown to the students as retrieval cues. The students then had to try and repeat the sentences verbatim.

Upon completion of the experiment, the recall scores were averaged. Meltzer and colleagues (2015) reported they used a subject-wise repeated measure ANOVA to analyze the data. In both tasks, the hypothesis was supported. Auditory suppression seemed to allow enhanced recall of the sentences. Interestingly enough, the semantically concrete sentences as opposed to the abstract sentences indicated higher levels of encoding within long term memory for the participants. The authors concluded the concrete sentences were repeated more accurately than the abstract sentences.

Meltzer and colleagues (2015) offer great insight for this current study. Their findings strongly supported the importance of semantically-elaborated sentences and the commitment within long-term memory. However, one issue within their experiment was they used a within-subjects design. This poses a problem because the participants may have become tired after the first task was completed. Or, the students may have had the opportunity to perfect memorization skills if they caught onto the hypothesis. Thus, those situations could have interfered with the results. The current study attempts to better this experiment by eliminating the potential carry-over effects found in a within-subjects design.

An additional study conducted that augments this current experiment was led by Jesse and Johnson (2016), who aimed to understand if children used initial labeling and audiovisual alignment to learn words. The authors used 48 Dutch toddlers for their experiment that averaged at the age of 25 months. For this experiment six videos were shown to each toddler that had two moving creatures in them, but no speakers. The toddlers’ eyes were also monitored during the experiment to measure attentiveness. One creature was green, the other pink, and both had Dutch names of “Kag” and “Zeut.” Three speakers that participated in the experiment provided voice overs for the videos when they were presented to the children. The speakers were instructed to speak to the children, but not to use any words that could define which character was which (e.g., “Zeut is running,” “Kag is green”).

Both groups of children were exposed to a pre-experiment. The experimental group was shown the character and his name, consistent with the actual video in the experiment. In the control group, the creature was labeled a name in the pre-exposure inconsistent with what was shown in the following video. The authors hypothesized the experimental group of children should learn the creature better as opposed to the control group. Once the videos started, the children heard the speakers say phrases such as “Look at Kag, isn’t Kag cute?”

The results of Jesse and Johnson’s study supported their hypothesis. Using a two-sample independent t-test, it was evident the children in the experimental group not only looked longer at the television screen, but also they learned the novel words used during the experiment. These finding proposed the children in the experimental group used the information they learned in both the pre-exposure phase and the exposure phase to learn words and associate the characters (Jesse & Johnson, 2016). The authors concluded inter-sensory material related to word learning. This means through integrating audiovisual information and connecting words to a meaningful sentence, learning ability is enhanced.

Pertaining to this current study, Jesse and Johnson’s findings suggest purely audiovisual circumstances are enough for word learning. Their study also offers background information on how toddlers learn that may be applied to our current study. While the sample for this current experiment consists of college students and the authors’ toddlers, the authors’ study is relevant because we can do further research in seeing if the same concept applies to more developed brains. However it is a disadvantage that Jesse and Johnson’s research was focused on toddlers rather than a prolonged lifespan development. This current study can add additional findings for Jesse and Johnson’s study because it seeks to understand a larger age range and how the brain better commits words to memory. This is because the focus will be comparing the results of those who memorize better when presented words in semantically-elaborated sentences or through word repetition. While Jesse and Johnson’s study was primarily on word learning, we will elaborate on this with sight word memorization.

Another study relevant to this current one was conducted by Nilsen and Bourassa (2008), which also focused on word-learning performance for beginning readers. The authors were specifically interested in determining if word-learning was promoted using regular (concrete) words or irregular (abstract) words. A regular word was defined as a word that the letter sequence followed typical spelling sound-mapping, such as the word “dream.” In contrast, an irregular word did not follow the typical spelling sound-mapping, such as the word “thread.” In this case, an example of a regular/concrete word would be “elbow,” and an example of an irregular/abstract word would be “temper.” It was predicted the regular/concrete words enable easier recall for children due to their direct sensory reference. To elaborate, it is easier for a child to remember the word “elbow” because it is a body part most every person has. The word “temper,” however, is not easily retrievable because it does not have a direct sensory or visual reference.

In Nilsen and Bourassa’s (2008) study, the authors had a sample of twenty-seven kindergarten students and nineteen first-grade students. The study was conducted over four sessions. 40 words were put into a word bank then separated into four groups. The word groups were presented in several formats: concrete–regular, concrete–irregular, abstract–regular, and abstract–irregular. In each session, the students were presented with one of the word formats randomly assigned to them. Each word was written on an index card that was shown to the student. The authors then read the word to the students twice, and the students in turn repeated the word after the author once. At the end of the session, the students recalled the words they had learned. The students were scored on a scale of 0-10. A score of “0” indicated no words were correctly learned, whereas a score of “10” indicated a perfect word-learning score.

The results of this experiment supported Nilsen and Bourassa’s (2008) hypothesis. The authors used an analysis of variance to examine the outcomes. It was concluded the children had learned the words that had greater semantic-richness more efficiently than the words that were abstract. For the current study, this would support the hypothesis semantics have a large effect on word learning, as well as word memorization. While the authors’ study focused on word learning with children, this current study’s focus is word memorization within adults. However, the two are relational because understanding how children’s brains learn may also enable us to better understand how adults may memorize or learn better as well. This assumption can be entertained because while children are more adult-dependent learners, as they grow older they become more independent learners. This would mean there will be a time when learning is less dependent on the educator and more dependent on the learner. Understanding the beginning methods of how words are integrated into memory may in fact assist in developing more advanced memorization and learning techniques in the future.

Research Goal

The goal of the current study is to investigate if memorization is enhanced when presented with visual line-drawn symbols under two different conditions: word repetition or semantically-elaborated sentences. Previous research has shown the importance of semantics in memorization as well as offered understanding of children’s brain development and how they best learn words. However, this study will focus specifically under which circumstances provide optimal word memory recall for students. To do this, participants will be exposed to 15 line-drawn symbols associated with words in one of two conditions randomly assigned to them. The hypothesis for this study is the learner will be able to memorize the given words presented to them better when presented with sentences that have concrete words within them, rather than when the word is repeated to them. This will help the learner associate a target word with its line-drawn symbol for recall.

Method

Participants

There was a total of 165 (18% male, 82% female) participants from Old Dominion University’s Research Methods in Psychology course. The participants received extra credit for their involvement. Average age of the participants was 27.

Procedure and Materials

This study was conducted online through the Online Psychology Laboratory. It was estimated it should only take 8-10 minutes for the participants to complete the experiment. Upon the participant’s agreement to complete the study, the first task is to specify the participant’s age as well as gender. Then, 15 line-drawn symbols and words associated with them were presented in one of two conditions — either a semantically-elaborated sentence, or word repetition — to the participants. For example, in the word repetition condition, participants would see a line-drawn symbol of a square while they hear the word “Pillow, pillow, pillow.” In the semantically elaborated condition, the participants would see the square and hear “Pillow. The pillow sits on the couch. Pillow.” The condition was randomly assigned to each participant. After the participants were presented the line-drawn symbols and words, they engaged in the memory recall portion of the experiment. The free recall portion was immediately after the presentation of the line-drawn symbols and words. The participants had to document the amount of words they remembered and enter their answer (0 to 15). For the cued recall section, the 15 line-drawn symbols were again presented and the participant had to write down which word they believed was associated with the symbol. Lastly, in the recognition recall, the words given during the presentation were mixed with other random words. The random words used in this part of the study were of the same semantic class. As the words were shown to the participant, the participant had to distinguish which words actually were used to identify the line-drawn symbol throughout the study. The purpose of measuring word recall in three different ways was to portray the findings through various comparisons. Researchers can take the data to compare any of the two tasks, or all three, to understand in which ways memory performance excelled and in which condition.

Demographic items of interest were the participants’ age and their gender. There were two different conditions in which the words were heard. The first condition was word repetition, and the second condition was semantically elaborated sentences. The three memory recall trials were free recall, cued recall, and recognition.

Results

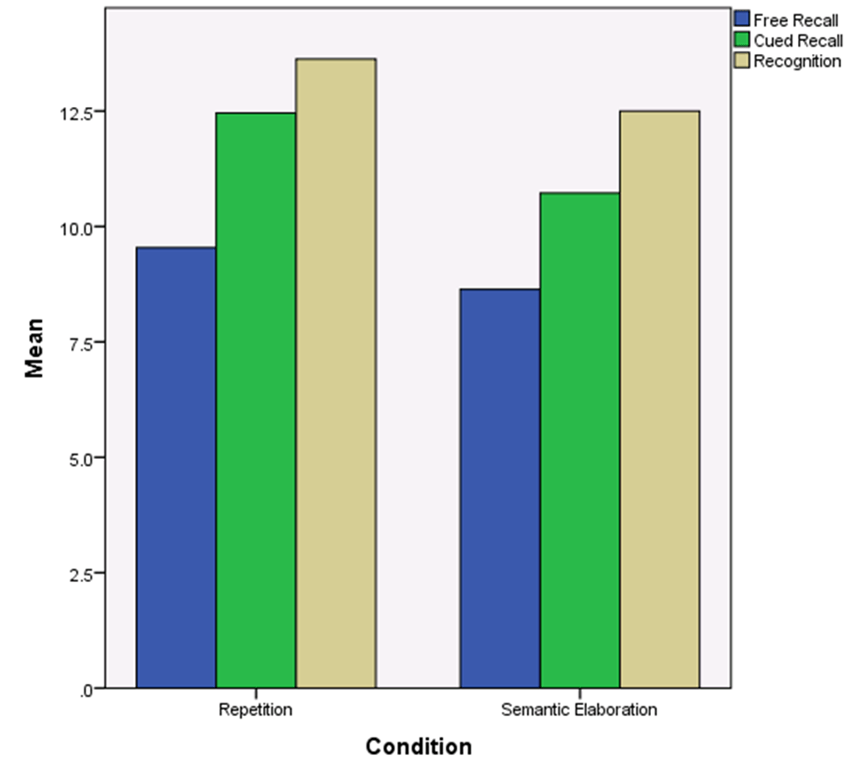

Data were analyzed using SPSS-PC version 22. An independent samples t-test was used to see if a difference in memory between participants who were exposed to word repetition and participants who were exposed to semantically elaborated sentence occurred. The results indicated no significant difference in memory between repetition (M=9.54, SD=3.43) and semantically elaborated sentences (M=8.64, SD=4.21) conditions when memory was measured using free recall, t(162)=1.471, p=0.143). However, there was a significant difference in memory between repetition (M=12.46, SD=2.50) and semantic elaboration (M=10.72, SD=3.37) when memory was measured using cued recall, t(162) =3.621, p<0.001, and for memory between repetition (M=13.63, SD=1.54) and semantic elaboration (M=12.50, SD= 2.26) when memory was measured using recognition, t(162)=3.603, p<0.001. Based on these results, we can conclude our hypothesis was partially supported, as participants who memorized using word repetition recalled fewer words than participants who memorized using semantic elaboration when tested using cued recall or recognition measures, but not when they were tested using a free recall measure.

Discussion

As noted in the results section, a statistically significant difference was discovered between the results of the participants who participated in either the word repetition condition or the semantically elaborated condition. The results of this study partially support the hypothesis. Therefore, these results suggest the memory retention of words is best when given in a situation in which rich, concrete words are present. Making the word functional as opposed to merely repeating the word can help memorization. The results show what was anticipated: cued recall was the easiest for the participants. Free recall may have not had a significant difference due to the lack of stimuli, such as being presented with the line-drawn symbol in the cued recall portion of the experiment, to help with the retrieval process.

The results of this study are similar to those of Duyck (2003). In this study, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. The three conditions were they were either given target words that were concrete, abstract, or non-words. The non-words were constructed to sound like real words. Once the experiment started, participants heard two words that consisted of one noun and one target word (either a concrete, abstract, or non-word). While the participants were being exposed to the words, they underwent articulatory suppression and repeated the word “the.” Upon the conclusion of the experiment, the participants then recorded the words they could recall.

Ultimately, Duyck (2003) found the participants who endured the articulatory suppression portion of the experiment still recalled a higher amount of words that were concrete. The non-words were recalled the least amount of times. Our studies are similar because both results support the connection between the richness of words used and memorization. While the participants in this particularly study did not undergo intentional articulatory suppression, experiencing articulatory suppression would undoubtedly cause a lapse in memory. However, although participants in Duyck’s study did recall less accurately in that condition, they still ultimately recalled more concrete words than the abstract and non-words. Therefore, Duyck’s study provides further support for our hypothesis.

Another study carried out by Madan (2014) looked into the connection between memory and high-manipulability words. The author hypothesized words were high in manipulability (i.e., words that signified objects that could be functionally interacted with) are easier to memorize than words with low-manipulability. Low manipulability words were described as words that represented nouns. Madan’s participants were undergraduate students. The participants were presented with eight word pairs, with each pair consisting of either two high-manipulability words, two low-manipulability words, or one of each presented in different sequences (HL, LH). As a distracter, in between presentation the participants had to answer simple arithmetic problems.

The results for Madan’s (2014) experiment supported his hypothesis. The words higher in manipulability were the easiest to recall for students. This was especially evident in the free recall portion of his experiment, which is different from the results from the current experiment. This is suspected because the free-recall portion of Madan’s experiment occurred after the cued-recall portion. In relation to this current experiment, Madan’s results support that automatic motor imagery influences memory. This is comparable to the results in the current study because the concept of semantically elaborated sentences improving memory is similar to high-manipulability words. In the semantic elaboration condition for the current experiment, the words were given context in the form of a sentence that related to the line-drawn symbol. Both encourage situations where relatedness is imperative, as well as elaboration.

While the hypothesis was supported for this experiment, there were several potential flaws in this experiment. One could be found in the sample of participants. Due to the sampling of college students, participants may have participated solely for the extra credit opportunity. In this case, data may be skewed due to disinterest in the study (Passer, 2014). The study may also have been performed quickly by the students without truly participating and putting forth the effort. The participants were also mostly female, which did not allow much diversity for gender within the study.

Another flaw is the experiment’s on-line nature. Because this experiment could be conducted from anywhere, environmental factors may take a toll on the participants (Passer, 2014). In some cases, if participants are at home they may have children or others around them that could cause a loss in concentration, which in turn would affect their memory ability. The participants also had the ability to read the background information of the experiment, which could allow the participants to understand the hypothesis. If the participants wanted to score well, they could easily have written down each word during the first phase of the experiment. This would result in a perfect score on the following three tests (free recall, cued recall, recognition), thus presenting false data. One final potential flaw was that although there was a relatively large sample of participants, only 70 of the 164 students were given the repetition condition. This means 93 students were in the semantically elaborated condition. This could explain why the average number of correct answers for the 70 students in the repetition condition was higher than those who were in the semantically elaborated condition.

In efforts to better this study in future cases, it may be beneficial to have participants come to a location where distractions can be eliminated. Monitoring the participants during the experiment would also be beneficial. If further studies are conducted, one may investigate getting a larger number of participants and having the conditions evenly distributed. However, maintaining the between-subjects design by only exposing the participant to one condition rather than both is critical to minimizing other confounds. This is because this particular experiment already contains three tests, and making the participant undergo each condition could result in fatigue or risk grasping what the hypothesis may be (Passer, 2014).

Because the hypothesis was supported in this study, further research on emerging programs that help children memorize words and learn to read more efficiently may be conducted. A new direction that may be explored could be creating experimental children’s books that specialize in teaching those who are between the ages of 1- to 3-years-old sight words. The books could use semantically elaborated sentences that focus on core words for children to know in order to effectively communicate with their caregivers. Because memorization of sight words is enhanced through these sentences, perhaps teaching toddlers these words could facilitate better learning skills — as well as discipline skills — as they age. Further studies may even evaluate the importance of learning sight words at an early age and the connection to the mastery of language in the later years of the child’s development.

This study’s hypothesis was supported by the data from the experiment. The use of elaboration seems to be more effective with memory than repetition. Other research supports this hypothesis as well. Using these findings can be beneficial for many people including those in the teaching practice as well as parents. Further research may be done to enhance learning environments for developing children as well as for people of all ages.

References

Association Memory Test (n.d) Online Psychology Laboratory. Retrieved from http://opl.apa.org/Experiments/About/AboutAMT.aspx

Benson, E. (2003, July/August). Remembering right. Retrieved April 08, 2016, from http://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug03/remembering.aspx

Duyck, W. (2003). Verbal working memory is involved in associative word learning unless visual codes are available. Journal of Memory and Language,48(3), 527-541.

Jesse, A., & Johnson, E. K. (2016). Audiovisual alignment of co-speech gestures to speech supports word learning in 2-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 145, 1-10.

Lee, B. Y. (2016). Facilitating Reading Habits and Creating Peer Culture in Shared Book Reading: An Exploratory Case Study in a Toddler Classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal.

Madan, C. R. (2014). Manipulability impairs association-memory: Revisiting effects of incidental motor processing on verbal paired-associates. Acta Psychologica, 149, 45-51.

Meltzer, J. A., Rose, N. S., Deschamps, T., Leigh, R. C., Panamsky, L., Silberberg, A., Madani, N. Links, K. A. (2015). Semantic and phonological contributions to short-term repetition and long-term cued sentence recall. Memory & Cognition, 44(2), 307-329.

Nilsen, E., & Bourassa, D. (2008). Word-learning performance in beginning readers. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 110-116.

Passer, M. W. (2014). Research methods: Concepts and connections. New York, NY: Worth.