Katie Arthur

One of the oddest things about Winnie-the-Pooh is that it is so embarrassingly funny. I am a grown adult, and I laugh out loud in the middle of my university library and have to apologize to my neighbors because Mr. Milne knows exactly how to pull a guffaw out of my throat at exactly the wrong moments. But, you ask, I thought it was a children’s story? Is it the sort of funniness we could imagine children enjoying? Is it below our mature threshold for thinking, adultish entertainment? In my reading, no. This is genuinely clever funniness for young and old, and the hilarity is a function of what narrative theorists call the implied reader. In the 1960s, Wayne Booth initiated theory on the implied reader, saying the text itself constructs a sense of the audience it intends, assuming knowledge and giving knowledge according to what it wants the reader to be. That ideal audience corresponds to nothing in the real world. The real readers of the text may or may not be anything like the reader the text asks for, but the sense the real readers get of the implied reader nonetheless shapes the way we receive the text. It is here that Winnie-the-Pooh is successful.

Winnie-the-Pooh incites two kinds of implied readers. It is a book either for older children to read for themselves or for adults to read out loud to younger children, and it works very well both ways. There are three kinds of humor in this book: humor for both the adult readers and the children listeners to enjoy together, and two kinds of humor only the adult readers will enjoy: the first, a humor accessible only to the adult readers as a function of the printed text, which naturally the young children will not appreciate; and the second, a humor that allows the adult to enter into the funniness of a child’s world. We will look at all three kinds of humor but dwell on the last for the longest because it is the reason I have to excuse myself from quiet places.

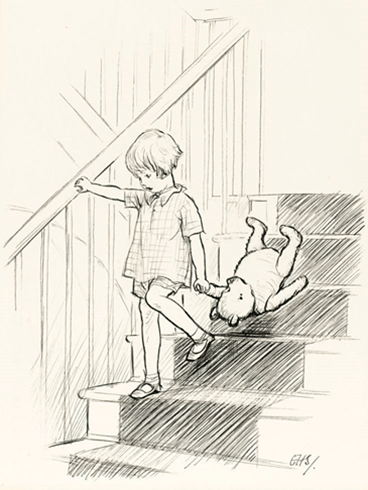

The humor made for both children and adults is the most easily explained. These are instances of simple confusion and embarrassment, like most of the comical things we encounter in our lives. In the fourth chapter, “In Which Eeyore Loses a Tail,” in order to find the tail, Owl suggests a reward be issued. “‘Just a moment,’ said Pooh, holding up his paw. ‘What do we do this — what you were saying? You sneezed just as you were going to tell me.’ ‘I didn’t sneeze.’ ‘Yes, you did, Owl.’ . . . ‘What I said was, “First, Issue a Reward.”’ ‘You’re doing it again,’ said Pooh sadly” (50, 51). This is purely delightful confusion between the sound of the word issue and the sound of a sneeze, and absolutely accessible to young and old minds. In Chapter II, “In Which Pooh Goes Visiting,” Pooh finds himself stuck in Rabbit’s front door, which was constructed to allow Rabbits and hungry Pooh Bears through, but had forgotten to take into account not-hungry-anymore Pooh Bears (32). People stuck places they should not be is just comical. This too, is simply an embarrassing situation most children and adults can relate to and laugh about. When Kanga and Roo come to the forest, and the animals have to decide what to do about these strange visitors, Piglet must, according to the plan, pretend to be baby Roo to trick Kanga into leaving. As Kanga, only fooled for a few moments about the difference between a baby pig and a baby kangaroo, gives Piglet a spluttering cold bath to continue the joke, both reader and listener can laugh at Kanga’s cleverness and Piglet’s sad and unheeded insistence he is not Roo and does not need to have this bath and take this medicine (106).

And then there is humor Mr. Milne threw in just for the reader, which the child listener would have no access to, unless he were an older child following along with the reading. This is located in the clever misspellings of certain things in the text. These animals are the toys of a young boy, so they do not naturally have a very large capacity for educated writing and reading, and yet, living in a forest, one finds the need for many things to be written. So Owl, the wise one, finds himself doing most of the spelling work when Christopher Robin cannot be found, and the result is funny for the reader. For example, on Eeyore’s birthday gift from Pooh, Owl writes “HIPY PAPY BTHUTHDTH THUTHDA BTHUTHDY. Pooh looked on admiringly. ‘I’m just saying “A Happy Birthday,”’ said Owl carelessly. ‘It’s a nice long one,’ said Pooh, very much impressed by it. ‘Well, actually, of course, I’m saying “A Very Happy Birthday with love from Pooh.” Naturally it takes a good deal of pencil to say a long thing like that’” (83). Mr. Milne took the time to write out in the text the funny misspelling that would only be seen by the reader. (Although, this might better fit into the first category. As we are supposing this to be read out loud, the pronunciation of the misspelled birthday message could be a point over which listener laughs at reader, and we might actually need to create a new category.) Another instance that is truly only for the reader is when Pooh brings Christopher Robin news of the flood waters in other parts of the forest, bringing with him a note he found in a bottle. He calls it a “missage,” and Mr. Milne continues, for the enjoyment of the reader, to spell it missage even when he has finished reporting Pooh’s actual words (142). And at Owl’s house are two signs which read: “PLES RING IF AN RNSER IS REQIRD” and “PLEZ CNOKE IF AN RNSR IS NOT REQID” (48). These are intelligible signs and can be read out loud to a child without problem, and the misspellings are just a little treat for the reader.

But the most interesting parts of the book for the adult reader are the places where Mr. Milne’s adult narrator speaks as if he were a child and allows the adult reader the joy of watching children think. In the introduction and first chapter, our narrator sets up the book as a collection of stories about a little boy named Christopher Robin and his stuffed bear. Really, Christopher Robin has told our narrator Winnie the Pooh has asked for some stories about himself, “because he is that sort of Bear” (4). Christopher Robin is the explicit narratee here, the one receiving the story. When Pooh needs a friend, “the first person he thought of was Christopher Robin” (9). Christopher Robin here interrupts the story with a question about whether or not Pooh really meant him, and the narrator assures narratee Christopher he did. We know, though, the story Christopher Robin and the listener Christopher Robin exist on different levels, one in the nursery listening to the story, and one in the Hundred Acre Wood being the story, and so they cannot be exactly the same. But good storytelling encourages the listener to feel involved, so we can let him think Pooh meant him. On page 10, Milne grants Christopher Robin permission to be called “you” by the narrator in a brief moment of dialogue. Then on page 11, the story continues with Pooh and Christopher Robin, we assume. But the Christopher Robin character is now called “you.” Before, the listener Christopher Robin was “you.” Now the character Christopher Robin is “you.” In this tiny switch hangs a great deal of the success of the book, because in it the reader is invited to be Christopher Robin listening to his father. As the narrator/narratee framework disappears with the disappearance of quotation marks surrounding the story and the reader receives the text in pure naked narration, the reader is addressed directly as “you.” In this way, the adult implied reader is asked to put himself in the shoes of a child, to put on a child’s perspective and think like Christopher Robin. The results are hilarious, and one of my favorite manifestations of this child-thinking is the time we are introduced to Piglet’s grandfather.

Piglet lives in a great beech-tree, and “next to his house was a piece of broken board which had: ‘TRESPASSERS W’ on it” and Piglet explains that it “was his grandfather’s name, and it had been in the family a long time” (34). We the readers know, as the narrator intends for us to know, that Trespassers W is not short for Trespassers William, as Piglet says, but for Trespassers Will Be Shot. If you are a child, though, trying to make sense of the world around him it makes perfect sense for a grandfather to be named Trespassers W. The funniness here is a function of the particular adult implied reader who does have a pretty good sense of the world around him, but who has hung next to his adult sensibility a child sensibility and has let them clink around a little at odds with each other. This clinking sounds like laughter. So a story can begin, “once upon a time, a very long time ago now, about last Friday,” and it both makes sense and is laughably wrong, because the adult knows how a child can feel that last Friday was an eternity ago and also know it has really only been a few days since then (4). And of course when you are a child trying to discover the North Pole, it makes perfect sense to look for a stick in the ground and preferably rather close to where you live, when you the adult knows it is actually a huge lonely snowy place very far away with no real poles at all (127).

To become an implied reader, to put oneself in the brains of someone else, is one of the greatest joys of reading narrative, and it is especially fun when the new brains are joyful and juvenile.

Works Cited and Related Reading

Booth, Wayne. The Rhetoric of Fiction. University of Chicago Press, 1961.

Iser, Wolfgang. The Implied Reader. Johns Hopkins UP, 1974.

Milne, A. A. Winnie-the-Pooh. E. P. Dutton & Co., 1961.

Prince, Gerald. “The Narratee Revisited.” Style, vol. 19, no. 3, 1985, pp. 299-303.