Kaitlyn Thornton Abbott

September 11, 2001: a day that goes down in infamy; a day that 2,977 Americans lost their lives. Across the globe, countries mourned with Americans; as a country, Americans found a solidarity they had not known before. Neighbors clung to one another, waiting anxiously to see what President George W. Bush would do in response. He, along with many other world leaders, pressured the Afghan government to convince the Taliban to hand over Osama bin Laden (U.S. military intelligence had confirmed he was responsible for coordinating the attacks on 9/11). When the Afghan leaders refused to cooperate, the United States invaded, with the blessing of the international community. Thus, the Global War on Terror was born. There have been several distinct eras of strategies, none of which have effectively worked to produce a long-term gain; so, the question remains: what other strategies have the U.S. military officials not tried, and of those, which direction should we pursue to retain American interests in the region and ultimately declare victory in the “War on Terror?”

Many ideas have come into play regarding the future policies of the war: privatizing the war, and a continuation of the Obama era strategy are common themes expressed from both sides of the political spectrum. Neither of these ideas are long-term conscious, and to assume so does a disservice to the United States and its allies. The steps the U.S. has to take are defining what it means to win; providing task, purpose, and direction to the ground troops; preventing the Taliban and other insurgencies from regaining and retaining key terrain, and ultimately retaining troops in country with no solidified “end date.”

In order to fully understand the concepts addressed in this paper, there are sub-concepts that must be defined and expounded on. Key terms addressed are: The War on Terror, Hearts and Minds Campaign, ROE (rules of engagement), COIN (counterinsurgency) operations, Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Inherent Resolve, SOF (Special Operation Forces), and joint operations. The legal definition of the War on Terror (Legal, Inc. 2017) states,

The War on Terror is an international military campaign launched in 2001 with U.S. and U.K. invasion of Afghanistan in response to the attacks on New York and Washington of September 11, 2001. It is a global military, political, legal, and ideological struggle employed against organizations designated as terrorist and regimes that are accused of having relationships with these terrorists or presented as posing a threat to the U.S. and its allies.

This term was phased out of official use by the Obama administration, replacing it with Overseas Contingency Operation. However, it is still used in everyday sectors, such as the mainstream media and politicians. The U.S. Armed Forces still utilizes this phrasing in the context of the Army’s Global War on Terrorism Service Medal (Appendix A). Counterinsurgency (COIN) operations (Joint Publication 3-24 ) are “comprehensive civilian and military efforts taken to simultaneously defeat and contain insurgency and address its root causes.” The Hearts and Minds Campaign is an example of COIN operations; the main component of this campaign was humanitarian needs; the Pentagon gave approximately two billion dollars to ground commanders to spend on a myriad of humanitarian needs — essentially, buy the Afghan loyalty, hope it’s a long-term investment, and that the Taliban won’t buy it back (McCloskey, Tigas, Jones, 2015).

Rules of Engagement (ROEs) are a directive issued by a military authority specifying the circumstances and limitations under which forces will engage in combat with the enemy. Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) was a U.S.-led coalition force with NATO allies that started October 21, 2001, and lasted until December 28, 2014; this was the official combat operation of the War on Terror in Afghanistan (CNN, 2026). Operation Inherent Resolve was formed on October 17, 2014, when the Department of Defense opted to “formally established Combined Joint Task Force — Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) in order to formalize ongoing military actions against the rising threat posed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria (inherentresolve, 2014). Special Operations Forces (SOF) are elite operatives in every branch of the U.S. military that has a specialized set of skills and who were key players used in training Afghan national forces. Joint operations, for the purpose of this paper, are tenets off which to plan and execute joint operations independently or in cooperation with our multinational partners, other US Government departments and agencies, and international and nongovernmental organizations (Joint Publication 3-24). There are key facets to this definition: there’s the national aspect of multi-branch operations (in which the Army, Air Force, Marines Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard perform operations in which assets are drawn from two or more branches); and multinational operations, which are operations where two or more countries are involved in military combat operations.

During the Bush Era (2001-2008), there was a pursuit of unilateralist foreign policy; the administration treated the individual nation-states as a regional “one size fits all” strategy. Iraq and Afghanistan are two distinct culturally significant entities; but then President Bush decided to connect them. To him, the strategy was simple: have a strong military front, destroy Saddam Hussein, destroy bin Laden, and the War on Terror will be over. The main tenets of his goals were simple: prevent another attack on American soil, capture and kill bin Laden, destroy al-Qaeda, and increase democratization of the Middle East as a whole (Katz). Whether or not he was successful is up to interpretation. The first phase of the operation, which was the initial military invasion of Iraq, was successful. U.S. forces quickly cleared the city and gained key territory in Iraq that led the U.S. to prematurely declare a “victory” in Iraq, without declaring a victory in the war. He was also successful in his endeavor to prevent another major terrorist attack on American soil. There have been attacks that ISIS has claimed but nothing to the extent of 9/11. Opponents of the Bush administration would argue he ultimately failed, and his strategy produced a worse environment for his successor to try to navigate (Katz). They argue he failed to capture bin Laden, his right hand, Ayman Al Zawahiri, and other key leaders in the al-Qaeda regime. This led to a follow on failure, which was not destroying all remnants of al-Qaeda. Because they were not destroyed, there was an increase both regionally and globally in signature al-Qaeda attacks. Bush also advocated for a strong democratic presence in the Middle East; instead of focusing in on the countries he had invaded, Bush opted for a regional strategy, which alienated some potential key players in the Global War on Terror, such as Morocco, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, Yemen, Kuwait, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia (Katz).

President Bush’s successor, President Obama, had a much different view on how to proceed. He made a dramatic shift from the unilateral foreign policy ideals of the Bush administration and instead honed in on a multilateral foreign policy. He campaigned heavily on withdrawing troops and focusing on domestic issues without having to be concerned with being the world’s police. When Bush originally invaded Iraq, Obama was loudly critical of this move and frequently commented on the approach to the War on Terror as a whole. Obama pursued a strategy between 2011 and 2014 called “off shore balancing,” which can be boiled down to four main tenets: an emphasis on withdrawing all ground troops, national forces doing the heavy lifting of operations, increasing drone strikes, and pursuing a medium footprint approach (Hannah, 2017). Proponents of this strategy and the Obama administration would argue this was the most effective way to win the war. They argue there were fewer combat deaths under Obama’s direction, and fewer terrorist attacks as a whole. Those who oppose this strategy would argue Obama’s ROEs made it harder to be more of an effective fighting force on the ground; forcing commanders to not take the prudent risk that military doctrine advises they take (FM 6-0). One of the key failures Obama made was announcing an official withdrawal date of massive amounts of troops from the region. Due to this being a public, and therefore accessible, announcement, terrorist organizations did exactly what any military organization would do: they waited it out until heavy multitudes of American forces left, then attacked with full force. This led to Obama having to readjust his strategy, angering his supporters who expected him to follow through with his promise on withdrawal.

The Trump administration has already made some major shifts in the Obama-era policy. By nominating retired General “Maddog” Mattis, he employed one of the most well-respected men in the armed forces, and Mattis became the driving force behind the defense policies of the Trump Era. He has reduced the ROEs that Obama integrated. There are pros and cons to this, however. It does up the risk of collateral damage, but it also allows commanders who are actually on the ground with the fighting force to be able to make decisions that will ultimately move us toward American interests. Afghan national forces are still being utilized within their own country; Mattis has shifted towards a policy of “training based” operations for them, i.e., utilizing the SOF personnel to train the Afghans to the best of their ability, imparting skills and techniques to effectively combat the Taliban, and any other insurgent groups.

Another key tenet of the Trump strategy is addressing the Pakistan issue. Pakistan has long been known as the harbor state of many terrorist organizations. They have smuggled weapons and provided a safe haven for multiple groups, specifically al-Qaeda. How Trump plans on addressing this issue is still to be determined. Both he and his Secretary of Defense have been extremely tight-lipped on the steps they plan to employ from here on out; however, the influx of troops suggests a withdrawal is far from being a potential strategy (Hannah, 2017).

One potential strategy the Joint Chiefs have discussed is privatizing the war. For the context of this paper, “privatizing the war” will refer to utilizing private defense contractors to execute military missions, which has both pros and cons. Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater Security, and former Navy Seal, is actively pushing the White House to turn the sole responsibility of the war over to private contractors. Both Secretary of Defense, Jim Mattis, and the current National Security Advisor to the President, retired Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, have given the nod they are open to bringing the idea to the drawing table, but there has been no admission to what extent. The idea of privatizing the war intrigues strategists, but the cons of utilizing the private sector far outweigh the pros it could potentially have. For example, the Blackwater scandal of 2007 gives reason enough to be hesitant regarding utilizing private contractors as the main effort. In September 2007, several private security contractors fired into a crowd in Nisour Square, Baghdad, killing fourteen unarmed Iraqi civilians (Apuzzo, 2015). While the individuals convicted of the massacre unequivocally argued they were only shooting at insurgents who fired on them, the issue remains: they were convicted in the American criminal justice system, not the military justice system. Military individuals should be held to military standards, especially regarding illegal or unethical acts. Members of the Armed Forces are held to the Uniformed Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), which addresses illegal actions and recommended sentences. Another con associated with the idea of privatizing the war falls back to funding. For example, the military is required to be in whichever country the Pentagon requires. At the strategic level, the goals are established for regions, and commanders take those desired end states and implement them at the ground level. Contractors, on the other hand, don’t answer to the Pentagon. Contractors are exactly that: held by a contract, which is reliant on limited funds for each contract. Once the contract is up, there is no guarantee contractors would want to re-up the contract, and if there is another government shutdown, then there are no funds for those contracts to be paid. In the private sector, if individuals are not getting paid, there is no legal expectation for them to continue to work. The idea of utilizing private contractors provides no long-term commitment to the United States’ end states, which ultimately could do a disservice to the mission. Beyond the potential legal ramifications and unguaranteed funding, the moral questionability rises. As noted above, the Blackwater scandal brought new attention to collateral damage and civilian deaths in the region. In contrast, the U.S. Army had a similar scandal regarding the murder of innocent civilians in 2006 by three lower enlisted soldiers. Contrary to utilizing the U.S. criminal justice system, they were convicted of violating UCMJ; sentenced to life in Fort Leavenworth (the military’s prison), the main proponent of the crime ended up committing suicide (Ricks, 2012). There was heavy scrutiny placed upon the Army and its commanders after this; these soldiers’ higher ups were held culpable in the court of public opinion; their reputations were tarnished. In comparison, the Blackwater scandal left Erik Prince just as wealthy; reputation fully intact. The military, as the Rand Corporation notes, is a distinct entity:

the military is the sum of its experience. When the nation outsources its battles, the military gains nothing in return, no battle-seasoned soldiers, no lessons hard-learned. Many of the contractors who have served in Afghanistan over the past 16 years have been dedicated staff who have placed themselves at risk to serve their country. Nevertheless, at a systemic level, there are numerous unresolved issues associated with contractor performance in Afghanistan. Militaries are massive and often frustrating bureaucracies, but the full measure of their work is not easily replicated in the private sector (Zimmerman, 2017).

On the alternate side of the argument, there are pros associated with the argument: for one, it would be cheaper, Erik Prince claimed it would cost less than ten billion a year, whereas the Pentagon spends approximately forty billion a year on defense aspects. Business Insider reports, “A 2016 Brown University study says wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have cost US taxpayers nearly $5 trillion dollars and counting. And, as the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction has found repeatedly, much of that has been lost to waste, fraud and abuse” (Francis, 2017).

The argument could be made the private sector always outperforms the government: in cost-benefit analysis, in efficiency, and in quality of product. Capitalists would argue regardless of the subject, government is consistently the wrong answer. However, that argument fails to take into account the fact the military is a profession of arms. There is a copious amount of doctrine associated with the military, step-by-step instructions on how to conduct key tasks, and a certain level of bureaucracy, yes; all of those things are associated with the private sector as well — except the doctrine. Military doctrine is not a negative concept that carries the same connotation as regulation. Regulations limit what an entity is allowed to do, or in what scope they are allowed to act in; doctrine, on the other hand, is a guiding principle that gives guidance and direction to leaders — a starting point that everyone begins with, so there is no discrepancies in explanation of executing a mission. The Rand Corporation explains,

In military operations, soldiers utilize doctrine — prescriptions for how to fight particular types of operations — to guide operations. Doctrine is unifying; a way, as Harald Høibak has said, to have “the best team without having the best players.”

Good doctrine specifies a desired end state and is underpinned by a theory of victory. Military contracting is not run on the basis of doctrine, but rather on company policies and procedures (Zimmerman, 2017).

Another policy that could be pursued would be a continuation of the Obama-era policies, with a mixture of Trump’s reduced ROE’s and some shifts in the execution of the policy. The main problem with Obama’s “medium footprint” approach and “offshore balancing” was not a lack of funding or troops available; the issue arises with the declination of the ground troops ability to be soldiers. ROEs are not released for public knowledge. Certain levels of security clearances are required to be able to access that information, or, you must be deployed to receive that briefing. Within this plan, the ideal would be for the U.S. to obliterate all insurgencies to the point their only course of action for hope of individual survival is peace talks and a negotiated settlement between them and the elected government. The key difference with this strategy would be not addressing a definitive end time for combat operations in country. As noted above, that was one of Obama’s key failures, and the Taliban exploited what he made known to both ally and enemy. The biggest departure from the Obama-era strategy would be a monumental shift toward a regional-based strategy. The Trump administration has already initiated this shift; according to Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis,

While we continue to make gains against the terrorist enemy in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere, in Afghanistan we have faced a difficult 16 years … Beginning last month, and for the first time in this long fight, all six Afghan military corps are engaged in offensive operations … During these recent months, there have been fewer civilian casualties as a result of coalition operations, although regrettably, Taliban high-profile attacks on civilians continue to murder the innocent (Defense, 2017).

The idea of addressing the problem as a regional strategy has more pros than cons; addressing the issues of Pakistan and harboring terrorists is a major factory in this strategy; to convince Pakistan they are better off working with the U.S. forces rather than against would be a major foreign policy victory for the United States, something even Obama failed to do. The major issues with this policy is addressing the outlying factors with other players. Pakistan and India have an increasingly aggressive relationship; expecting them to both effectively work with the United States and, by extension, each other, is a tall order. Other factors to this strategy include troop increases; to be an effective fighting force regionally and providing the support that regional actors need, the number would, at the very least, be in the low five figures. This could be considered both a pro and a con; it would increase the spending of the DOD, but it is arguable increasing troops in the short term would allow us to be there for a lesser timeframe than originally proposed. Opponents of this strategy argue this strategy would increase civilian deaths, therefore increasing the terrorism aspect. Afghan nationals want security; they’ll sell it to the highest bidder. If the bidder happens to be the Taliban, then the Afghans will support them. The Taliban grows when they see U.S. forces as the enemy; the more civilians get killed and the more property gets damaged, the more the Taliban will be able to use to recruit young men and even women into their ranks.

The third potential strategy is to completely readjust how we see the war. The only other war the United States has fought that even remotely reflects the War on Terror is the Vietnam War. The Taliban, just like the Vietcong, are fighting an insurgent warfare with guerrilla tactics. Ambushing American patrols, IEDs (Improvised Explosive Device), and being able to melt into the civilian population are key reasons they are both hard to find and kill.

The U.S. could take a step back from the current strategies and instead implement more special forces operations, focused solely on independent missions, (rather than vague end states established by the Pentagon) and training the Afghan nationals forces. In essence, this strategy would be guerilla warfare: fighting insurgencies with insurgent-type tactics. SFC Galer, an Army Special Forces soldier whose area of expertise is engineering, explains, “Special Forces used to have four sectors in Afghanistan; essentially, they would divide the country in fourths, and the commanding general of Afghanistan would attach us as he or she saw fit. We have a very special set of skills; utilizing the Special Forces to train Afghan National Army is a waste. Utilize Special Forces to train specialized groups to obtain the same goal with less people and do a better job of it.”

All of these potential strategies have merit; they also come with an exceptional amount of criticism. Most of that criticism comes from domestic political polarization and an inherent belief as to whether the United States should even have troops in the Middle East. There was bipartisan support when President Bush originally invaded; patriotism and nationalism soared due to the atrocities seen on September 11, 2001. The idea of revenge was tangible in America. Sixteen years later, 6,915 American lives lost, and the question remains: how much longer will our soldiers, marines, airmen, and sailors be deployed to fight this “War on Terror?” The answer is harsh, albeit simple: until the threat is no longer present. The United States is the greatest military power in the world; the Taliban has no technological capabilities that can touch our prowess in the air, land, or sea. The issue is not military readiness or capabilities; the issue is the United States has not effectively defined what American interests are in the region, which leaves room for the Pentagon to claim our end states have not been met. That is the first step to success.

Defining American interests is difficult; the first step is taking the vague concepts of “promoting democracy in the region” and “ending the Taliban, sister cells, and offshoot groups,” by giving them measurable end states that will be able to be checked off as the military executes the missions and successfully achieving the end states. For the vague concept of promoting democracy in the region: the United States has to define success. The Obama Era focused success as being a shift toward democratic values, promoting human rights such as education for girls or that nation becomes Westernized through infrastructure. The Trump administration is shifting the definition of success to being a regional success; focusing on the ground goals of the military, not built in a context of vague aspects even the generals at the Pentagon struggle to explain what that looks like beyond political talking points.

The Trump administration has already started defining the regional aspect by changing the strategy to “Southeast Asia Strategy.” This still fails to address the issue of who the key actors in that strategy are. Within the idea of a regional goal, the key players need to be Afghanistan, all the countries that border it (Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan), and include India. Afghanistan (the citizens) are concerned with security. To be able to guarantee security for the Afghan people while ultimately moving toward the goal of reducing U.S. presence in the region, the diplomatic aspects of improving relations of Afghanistan with its neighbors must be a top priority for the United States. This falls into the follow-on steps of the recommended strategy.

The Taliban must be obliterated, and the neighboring states must be willing to work with Afghanistan and the United States to ensure no remnants remain. Pakistan cannot be allowed to continue harboring terrorists. Doing so completely undermines the United States and the region’s safety as a whole. President Trump, in August of 2017, addressed the Pakistan problem; the Taliban heard his words and released this statement, “It looks like the US still doesn’t want to put an end to its longest war. Instead of understanding the facts and realities, (Trump) still shows pride for his power and military forces.” They have vowed to continue their fight to remove American forces from the region.

Some would argue the Taliban simply want the war to end and for Americans to remove the troops in the region. Giving into this demand is a win-win: withdraw the troops, terrorist attacks stop. This argument is shortsighted and ignores the logistics of the war, and the second and third order follow on effects of withdrawing. For example, if the U.S. were to simply withdraw all troops from Afghanistan, the Afghan National Army (ANA) would have to pick up the slack; terrorism is like a bacteria: there has to be a certain environment for it to grow and thrive. If the United States leaves, that would create a vacuum of security. The Afghan forces are still ineffective against the Taliban; they struggle to coordinate the logistics of war: weapons, fuel, and ammunitions. Soldiers win battles; logistics wins wars. The lack of ability in the ANA to coordinate the key components needed to fight the Taliban will provide them the exact environment they need to thrive: the promise to the Afghan people they are the only effective ones who can provide security, provoking the anger of the Afghan people who feel abandoned by the United States.

The argument of simply withdrawing has no merit because the Taliban is fighting an inherently different war than the United States is: they are fighting an ideological war. This war is built upon a hatred for the West and everything it stands for. In contrast, the United States is fighting a cultural war, one focused on promoting democracy, protecting human rights, and removing those who pose a threat to those ideals. The U.S. is the international symbol for a strong, victorious Western culture, which is associated with Christianity (whether or not the U.S. has an official religion or is even a majority Christian). So, to continue to stay in power, the Taliban incites hatred of the West and Christian values by tapping into the base of moderate Muslim followers. This is their power: people. Retaining American troops in-country allows for us to continue to promote the Afghan government and provide assistance to the Afghan people. If the Afghan people do not grow to see the United States as the dictators, then the Taliban loses their momentum. The American forces need to start shifting into a view that is a support aspect of the Afghan National Army, not the ones doing the fighting for them. To be able to do this means utilizing key subject matter experts to continue teaching and training the forces, implementing more of a U.S. military style structure to the ANA, so they become an effective fighting force.

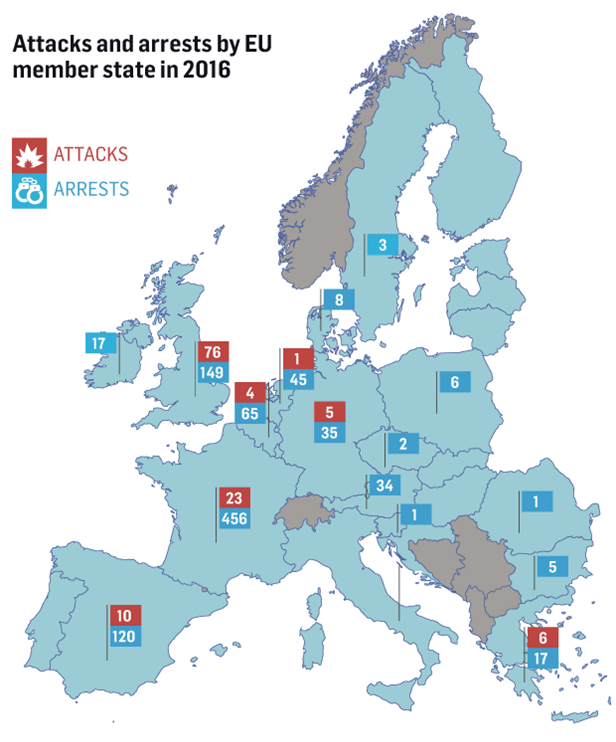

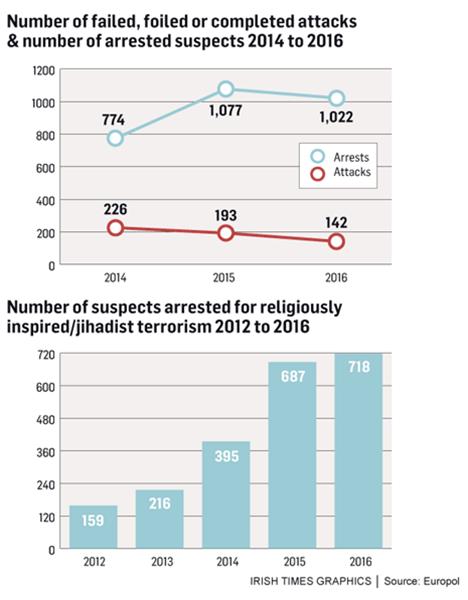

In continuation with this plan, American intelligence forces need to become more open with U.S. allies, which would reduce massive terror attacks in the Western world, not just the United States. The European world also need to work with the United States. Some major terrorist attacks since 2001 include, but are not limited to: Bali, 2002, over two hundred dead; Russia, 2002, one hundred seventy dead; Madrid, 2004, one hundred ninety-one dead; Brussels, 2014, four dead; France, 2015, seventeen dead (Graphics, 2015). The Trump administration has ultimately done the United States intelligence community a disservice by its flirtation with Russia; many U.S. allies have decided to keep their intelligence behind closed doors, in fear the United States would share classified information, whether intentionally or not. NATO needs to become more involved in the War on Terror, allocating more troops to be used where needed; promoting a global war on terror means we need to have global allies: not the U.S. fighting the war on behalf of the world. To be able to effectively continue to eradicate terrorism, we have to have the global and military support from allies, instead of simple words of unity and love after yet another major terror attack on Western soil. Europe has faced more terror attacks in the past three years than the U.S. has faced since 2001. Dimitris Avramopoulos, EU Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship said, (Europol, 2017)

The recent terrorist attacks in Europe are a stark reminder of the need for all of us to work together more closely, and build on trust. Trust is the basis of effective cooperation. Fighting terrorism will remain at the top of our common political priorities for the time to come, not just in Europe but globally. For the safety of our citizens, and for the cohesion of our societies, we need to step up our information exchange and our cross-border cooperation at all levels.

Opponents of sharing intelligence outside of regional structures argue the European Union has thwarted one hundred forty-two attacks in 2016. According to EuroPol,

In 2016, a total of 142 failed, foiled and completed attacks were reported by eight EU Member States. More than half (76) of them were reported by the United Kingdom. France reported 23 attacks, Italy 17, Spain 10, Greece 6, Germany 5, Belgium 4 and the Netherlands 1 attack. 142 victims died in terrorist attacks, and 379 were injured in the EU. Although there was a large number of terrorist attacks not connected with jihadism, the latter accounts for the most serious forms of terrorist activity as nearly all reported fatalities and most of the casualties were the result of jihadist terrorist attacks (Europol, 2017).

However, opponents of sharing intelligence with allies by citing the European Union disprove their own point: the EU is a regional structure that is only able to thwart the terrorist attacks it has by utilizing the member states within the organization and sharing intelligence. The EU does discover and prevent many terrorist attacks, and the ratio is impressive. The issue is the EU has still faced more terrorist attacks than the U.S. since 2014, and there is a growing trend (Appendix B). Since 2001, the U.S. has experienced less than twenty major terrorist attacks.

The final strategy component comes with the economic aspect of NATO and the U.N. supplying the funding to Afghanistan to be able to continue to fund its military operations and working with the country to improve its infrastructure that will go toward the Obama-era goal of “nation building.” However, the United States cannot be the ones to bear that burden anymore. Development of Afghanistan is important and should be something the global community strives for. The U.S. did not go to Afghanistan to nation build, nor should we be footing the bill for that process. The U.S. should measure success in Afghanistan when Afghanistan is a stable enough nation to be able to effectively manage its internal and external security, to include being able to eradicate and prevent terror bases from being established in its borders. When Afghanistan is secure in that manner, the U.S. will be able to start the withdrawal of its troops. Until that happens, there is no legitimate reason to remove our military forces in the region, except to bow to political pressure of bringing Americans home. Campaigns are built on the rhetoric as well as the rhetoric of national security. Instead of appealing to domestic pressure, the U.S. needs to focus on the goals it has in Afghanistan and actively work toward achieving them.

If the United States were to remove its troops in the region before tangible progress is being seen in Afghanistan, it would have severe implications on the perception of the United States and its military capabilities. The United States has influence in the region partially because we have so many troops stationed there. If the U.S. wishes to continue its influence on promoting democratic values and honest and fair elections, then the U.S. also needs to retain troops in Afghanistan until the nation has sufficient internal and external security. Another fallout of the U.S. pulling out of the country prematurely is the international perception, from both ally and enemy alike.

For example, in 1973, the U.S. pulled out of Indochina and as a result, there was significant backlash both domestically and abroad; friends feared the U.S. would not be willing to help defend them, and enemies saw it as military weakness and resolve (Katz). The perception created internationally if the U.S. were to withdrawal, would create an emboldened insurgency in the country, and within other heads of state who are not allies of the U.S.

Iran upping their nuclear game, even with the current Iran Nuclear Deal in place, presents an interesting foreign policy problem; countries who resent having American presence in the region would be encouraged to up the ante to pressure American forces to leave the remainder of the region as well, not just Afghanistan. Allies in both the Middle East and the Western world would hesitate before calling on the United States from that point on. Israel, our key ally in the region, is vital. If the U.S. decided to pull out early, we would lose the faith and confidence of the only democratic, capitalist nation in the region (Katz).

China and Russia both would have major geopolitical interests in the region if the United States were to leave the region. Russia has a messy history with Afghanistan (the Soviet-Afghan War of 1979) and is eager to gain world prominence again. China has actively contributed monetarily in the form of humanitarian projects and development assistance, and there are several reasons China has an interest in the country: geographically, it is located the crossroads of Central and South Asia, meaning its placement between India and Russia becomes of great importance militarily to China (Massey, 2016). Second, there is great economic value to Afghanistan; there is a vast amount of the country that remains undiscovered regarding natural resources; China wants to be at the forefront of that search. According to a U.S. report in 2010 (Massey, 2016),

Further untapped natural resources in Afghanistan are supposed to be worth $1 trillion. In particular, Afghanistan has been a source of the gemstone lapis lazulis, which generated roughly $125 million trade value in 2014. But the mining of the stone has led to a conflict in recent years between local security forces and the Taliban as they gained more control over the country. Mining has the potential to generate large amounts of revenue and growth for Afghanistan if the country could establish capacities to impose legal mining.

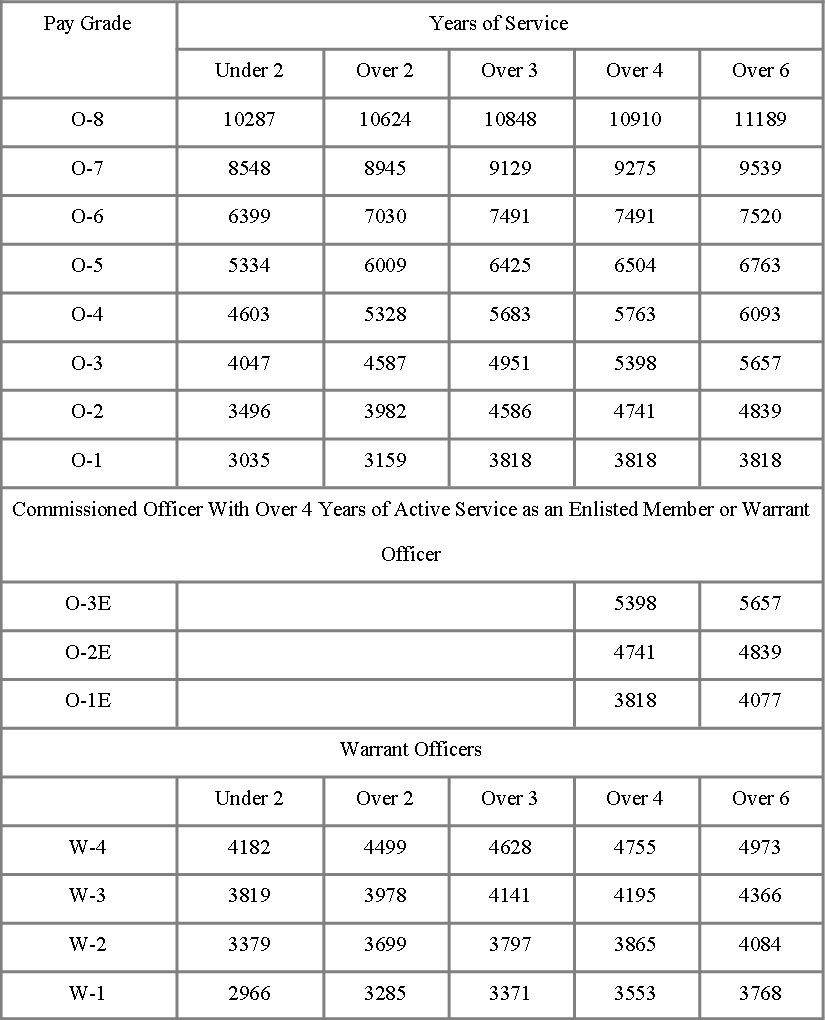

Currently, the rotations for the Middle East are considered deployments because of the combat related nature of the missions. There are several entitlements military members receive while being deployed to a combat zone. For example, all deployed soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines receive their base pay, which is based on rank (Appendix C), Combat Zone Tax Exclusion (CZTE), Hostile Fire Pay (HFP), Hardship Duty Pay-Location (HDP-L), Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH), and Family Separation Allowance (FSA). For Afghanistan, this equals out to approximately an additional $100 per day, which excludes the base pay of rank and the cost of living quarters and sustenance. The Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Overseas Contingency Operations budget is $64.6 billion, which is due to the nature of the jobs in the country and the pay those deployed are entitled to. Temporary Duty (TDY) in contrast, are shorter assignments done on a rotational basis into a specific country, while stationed in another, usually neighboring, country. For example, many units will be officially deployed to Qatar but perform rotational TDYs into Afghanistan. In 2014, the Pentagon attempted to reduce costs of the budget by reducing HFP in non-combatant countries, such as Qatar or Kuwait. Many service members got upset with this change in policy, so much so Congress intervened in the decision; those deployed in what is considered “non-combatant areas” will still receive HFP due to TDYs, but it will be less so than those stationed in Afghanistan. The Pentagon should continue this shift as the nature of the missions change and as the intent from the President and Joint Chiefs comes down to the ground level troops. As the strategy shifts more toward a regional and training based strategy, the pay allowances should be shifted toward non-combatant type pay, only done so when the rotations of TDYs enter into the imminent danger areas. This allows for the DOD to allocate more funds to the development of the training doctrine for the Afghan forces and allows for more trainers and training programs to be developed and implemented.

In essence, Afghanistan is a winnable war. It is a different war than we have ever fought, with a strategy that has been dwelt on for almost two decades; previous administrations have promised the idea of a regional strategy without actually delivering. Pakistan is a consistent problem; their troubled relationship with India causes more harm in the region than good. Pakistan is a major wild card in the War on Terror; they take money from the U.S. with one hand, and in the other provide a safe haven for terrorists. No longer can the U.S. afford to support Pakistan and still achieve the end states set out that ultimately result in a stronger, safer Afghanistan.

The War on Terrorism in Afghanistan is a foreign puzzle anomaly; there are so many aspects to consider, with many moving parts, both state and non-state actors who would be affected by any decision made. The United States can declare victory in Afghanistan and eventually remove troops from the country, but that cannot happen until Afghanistan is a stable nation, which cannot happen until the Taliban is eradicated, as well as sister cells and offshoot groups. Beyond the internal struggles Afghanistan faces, there are the external struggles from other sovereign states who all would love nothing more than to capitalize off the failures of the United States and Afghanistan.

Several strategies have been brought forth to the drawing board regarding the future of the strategy for Afghanistan. Privatizing the war has more negatives associated with it than it does positives, the biggest factor being the monetary aspect of contracts and the potential for a government shutdown; contractors will only work if they’re being paid. Obama’s medium footprint strategy failed to incorporate a regional strategy that utilized regional actors effectively. Reducing the ROEs does come with the potential for collateral damage, but utilizing the Army doctrine of Mission Command (FM 6-0), the Pentagon would provide the intent and commanders would implement it into the missions that meet that intent. The overall strategy the United States should pursue is defining our goals in a more tangible sense, preventing the Taliban from regaining control, preventing any further major terrorist attacks on the Western world, and ensuring Afghanistan becomes a stable nation; one who can defend itself from internal and external security struggles. These strategies can be broken down into further goals: by removing key leaders of insurgent groups and hold key terrain we’ve taken from their control. Once we have key terrain to operate in, we can start to crush new terror groups before they gain prominence in an area through providing security to the Afghan people, therefore removing a desire to turn to the Taliban for the desired security.

Bibliography

“2017 EU Terrorism Report: 142 failed, foiled and completed attacks, 1002 arrests and 142 victims died.” 2017. Europol. https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/2017-eu-terrorism-report-142-failed-foiled-and-completed-attacks-1002-arrests-and-142-victims-died (November 21, 2017).

“2017 Iran Military Strength.” GlobalFirepower.com – World Military Strengths Detailed. https://www.globalfirepower.com/country-military-strength-detail.asp?country_id=iran (November 21, 2017).

Apuzzo, Matt. 2015. “Ex-Blackwater Guards Given Long Terms for Killing Iraqis.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/14/us/ex-blackwater-guards-sentenced-to-prison-in-2007-killings-of-iraqi-civilians.html (November 21, 2017).

Developed by NCCM Thomas Goering USN (Retired). 2016. “NCCM Thomas Goering USN (Retired).” 2017 Military Pay Chart 2.1% (All Pay Grades). https://www.navycs.com/charts/2017-military-pay-chart.html (November 21, 2017).

“Effects of South Asia Strategy Already Being Felt, Mattis Tells Senate.” 2017. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE. https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1332699/effects-of-south-asia-strategy-already-being-felt-mattis-tells-senate/ (November 21, 2017).

Francis, David. 2017. “5 facts about the plans to privatize the war in Afghanistan.” Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/privatizing-war-in-afghanistan-2017-8 (November 21, 2017).

Griffiths, James. 2017. “Trump calls for Pakistan, India to do more on Afghanistan.” CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2017/08/21/politics/trump-afghanistan-pakistan-india/index.html (November 21, 2017).

Hannah, John. 2017. “Afghan president says Trump war plan has better chance…” Foreign Policy. http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/09/01/trumps-afghan-strategy-could-actually-work/ (November 21, 2017).

“Home.” Operation Inherent Resolve. http://www.inherentresolve.mil/About-Us/ (November 21, 2017).

Joint Chiefs. Joint Publication 3-24. Joint Publication 3-24.

Katz, Mark N. “Assessing the Bush Strategy for Winning the ‘War on Terror.’” Middle East Policy Council. http://www.mepc.org/commentary/assessing-bush-strategy-winning-war-terror (November 21, 2017).

—. “Assessing the Obama Strategy toward the “War on Terror”.” Middle East Policy Council. http://www.mepc.org/commentary/assessing-obama-strategy-toward-war-terror (November 21, 2017).

—. “Implications of America Withdrawing from Iraq and Afghanistan.” Middle East Policy Council. http://www.mepc.org/commentary/implications-america-withdrawing-iraq-and-afghanistan (November 21, 2017).

Legal, Inc. US. “USLegal.” War on Terror Law and Legal Definition | USLegal, Inc. https://definitions.uslegal.com/w/war-on-terror/ (November 21, 2017).

Massey, A.M. 2016. “China’s interests in Afghanistan.” China Policy Institute: Analysis. https://cpianalysis.org/2016/09/05/chinas-interests-in-afghanistan (November 21, 2017).

McCloskey, Megan, Mike Tigas, and Ryann Jones. 2015. “U.S. Spent $2B on ‘Hearts and Minds’ in Afghanistan.” The Fiscal Times. http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/2015/05/15/US-Spent-2B-Hearts-and-Minds-Afghanistan (November 21, 2017).

“Military Deployment Pay – Entitlements While Deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, HOA.” 2015. Military4Life. http://www.military4life.com/military-deployment-pay-entitlements-while-deployed-to-iraq-afghanistan-hoa/ (November 21, 2017).

“Operation Enduring Freedom Fast Facts.” 2016. CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2013/10/28/world/operation-enduring-freedom-fast-facts/index.html (November 21, 2017).

Ricks, Thomas E. 2012. “Back to ‘Black Hearts’: Why this book stands out so much as a study of the Army.” Foreign Policy. http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/06/20/back-to-black-hearts-why-this-book-stands-out-so-much-as-a-study-of-the-army/ (November 21, 2017).

SFC Galer, Joshua. Personal Communication. November, 2017.

“The National Military Strategic Plan for the War on Terrorism: An Assessment.” 2015. HOMELAND SECURITY AFFAIRS. https://www.hsaj.org/articles/170 (November 21, 2017).

“Timeline: Terror Attacks Linked to Islamists Since 9/11.” The Wall Street Journal. http://graphics.wsj.com/terror-timeline-since-911/ (November 21, 2017).

Zimmerman, S. Rebecca. “Is It a Good Idea to Privatize the War in Afghanistan?” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/blog/2017/08/is-it-a-good-idea-to-privatize-the-war-in-afghanistan.html (November 21, 2017).

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C