Christopher Rush

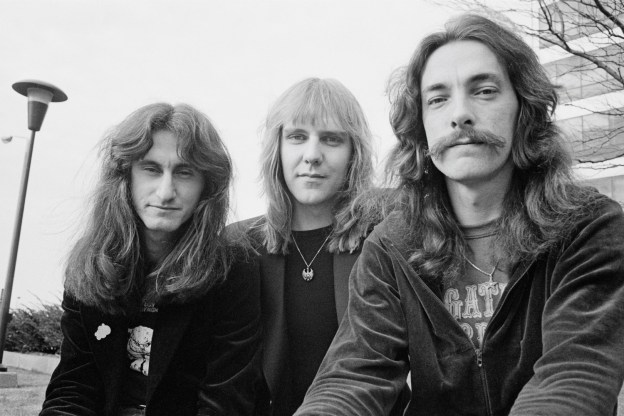

Finding My Way: Rush and Fly By Night

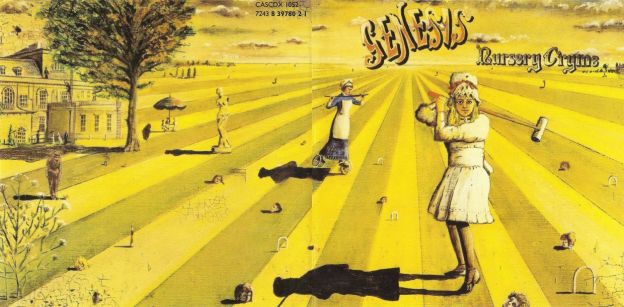

Like so many of the prog rockers we have been examining, Rush started out as a would-be rhythm-and-blues band, as evidenced by the beats and lyrics of their eponymous debut, and the bandmates met at school. That is about where the similarities end. Unlike the boys of Genesis, who mostly grew up in well-to-do families, Geddy Lee’s father spent time in a concentration camp and died when Geddy was twelve. His grieving process prevented from listening to music for almost a year. After that year, Geddy was introduced to Alex Lifeson, whose Yugoslavian parents likewise moved to Toronto after World War II. Perhaps because Rush is a Canadian band and not English like everyone else in the main wave undoubtedly labeled as “prog rock,” many critics and historians of prog ignore them altogether.

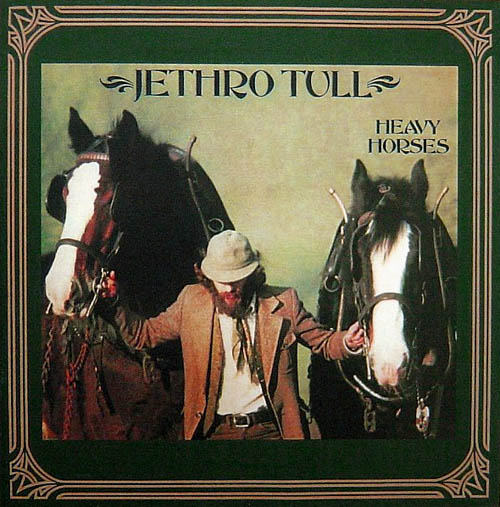

To be fair, they are also a little younger than Tull, Genesis, and the others, and their debut did not occur until the main era of prog was just about over in 1974. Growing up listening to rock music in the late ’60s, they certainly had great musical role models to emulate as a bassist and guitarist, and they had the benefit of also listening to early Tull, Yes, Genesis, and the popular Van der Graaf Generator. So they are somewhat on the “outside” of the core of prog rock, if such a thing exists. That is in part to the temperament and musical affinities of their first drummer, John Rutsey, who was the de facto leader of early Rush.

Besides getting a manager, Ray Danniels (the only manager they ever had), and the acquisition of arguably the greatest drummer in rock history (a subject for another time), perhaps the most influential event that propelled Rush’s career came from an unlikely source: “In 1971, the government of Ontario made a decision that would alter the history of progressive rock. The Canadian province dropped the drinking age from twenty-one to eighteen.”

Rush’s eponymous album, the only release with drummer John Rutsey and Lee and Lifeson composing most of the lyrics, much like Tull’s debut This Was and Genesis’s double debut albums, is enjoyable likely more for nostalgic reasons (one hesitates to say “quaint”) as the beginning point of a band that was one drummer away from becoming a whole new entity. It is enjoyable but rather middling R&B/rock, and possibly even “Working Man” would have been forgotten had the band not kept it alive on most tours over the next forty years.

Like Tull and the Moody Blues and others, after getting R&B and cover songs mostly out of their system, Rush became a unique musical entity: a heavy/progressive rock power trio with a social conscience and literate drummer. Gene Simmons says of Peart in those early days: “Neil is a self-professed and/or otherwise reading hound. He likes to read. Yeah, after the show he goes back … reads. Anthem by Ayn Rand, Foundation trilogy by Isaac Asimov, all that stuff.”

As appropriate as the first song, “Finding My Way,” was for Rush, Fly By Night’s opening song, “Anthem,” perfectly captures the new direction musically and lyrically of Rush 2.0. Much has been said – too much – of Neil Peart’s disproportionately short-lived interest in the objectivism of Ayn Rand (certainly disproportionate to the lasting recrimination Rush suffered), but here Peart’s belief in the need for hardwork and perseverance (and general optimism in mankind, if not individually: “Live for yourself / There’s no one else more worth living for”) is unabashedly on display.

Also on display is the almost mid-’70s requisite homage to JRR Tolkien, with “Rivendell.” If Led Zeppelin can unashamedly sing of Tolkien’s creation, certainly Rush should be able to as well. But those two widely disparate sources of inspiration (Rand and Tolkien) are likely only to be found in the same place on a Rush album – the fans of both radically different worldviews rarely commingle anywhere else. Bradley J. Bizer says Peart’s Tolkienian influence is also heard in Rush’s first prog-like mini-epic, “By-Tor and the Snow Dog,” but it may just be more a sign of Peart’s diverse reading of fantasy and other speculative fiction. Peart admits being fascinated with Chariots of the Gods around that time as well. Regardless, for our purposes, it has taken very little time to find direct literary influences on this prog rock band.

We Have Assumed Control: Caress of Steel and 2112

Caress of Steel may be more the black sheep of the Rush canon than Rush, oddly enough, though it does begin Rush’s rest-of-career-long relationship with cover artist Hugh Syme, another important component of prog rock music. The first side is an eclectic mix of song styles and subject matter, from the humorous “I Think I’m Going Bald” (prog rock’s sense of humor is, like our present exploration of literary influence, another underexplored component of the genre), to the grand and personal histories of “Bastille Day” and “Lakeside Park” and the next progression in prog epics, “The Necromancer,” another song with clear influences from Tolkien. The liner notes at the end of the lyrics for “Necromancer” include the Latin tag to Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus as well (admittedly somewhat hard to read in my CD version of the album). Perhaps it is this diversity (what critics call “lack of unity”) that has led to the album’s general disfavor.

The second side of the album is the first of Rush’s three album-side-long prog epics, “The Fountain of Lamneth,” but unlike Genesis’s “Fountain of Salmacis,” this fountain is not based on any mythological or literary inspiration directly. Birzer suggests the protagonist of the song sloughs of his conformity after drinking the draft from “the cask of ’43,” which the protagonist says “give[s] me back my wonder,” could be a reference to The Fountainhead, published in that year. At the end of the journey, which Birzer in his zeal likens to most journeys in “the western tradition of Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Tolkien,” Popoff says “the journey has not resolved itself, that now there are more questions than answers, that the birthing at the beginning merely put the hero into a cycle of perpetual motion.” This interpretation would likely make more sense than Birzer’s desire to cast “Lamneth” in a more traditional light, since it foreshadows much of Rush’s seeming preference for the searching itself more than the resolution.

From hindsight, of course, “Lamneth” is easily overshadowed by what comes next, though it does us well to remember there would have been no 2112 without the early experimentations of “Necromancer” and “Lamneth.” Lee and Lifeson both highlight how important it was for them to experiment with longer forms of composition, though Lee says in retrospect it was “kind of absurd. … And I think there are some beautiful moments, but a lot of it is ponderous and off the mark.” Says Lifeson, “You smile and shake your head and you go, ‘What was I thinking?’”

2112 is many things to many people. For Rush, it was a last-ditch effort to create the kind of music they wanted to create, flying in the face of the critical, financial, and touring disappointments from Caress of Steel. For many critics, it was a justification of the disdain for the atypical music from the late-to-the-prog-party Canadian trio. ’60s British counterculture insider Barry Miles was one of several vocal antagonists to Peart’s tribute to Rand. As Weigel puts it, “he (Miles) had read up on Ayn Rand and was utterly offended that Rush had written a paean to her with 2112.” For many (if not most) fans, the opening synthesized outer-space sounds of the Overture leading into the syncopated hits and the driving full intro are the very reason they love music.

Lee says, “2112 was part of a progression to us. … And we had this concept in our minds that we love progressive music, but we also love to rock. We like The Who as much as we liked Genesis and Yes, and to us, The Who were still a progressive band even though they were more of a hard rock band. … We wanted to be the world’s most complicated thee-piece band.” Lee continues in that section of Popoff’s work to describe their evolution beyond an R&B band and even beyond the by-then fairly static conception of prog rock, which they clearly loved, into the heavy rock band most evident by Counterparts. Peart seems to have spent much of the next thirty years downplaying the significance of Randian philosophy on himself and his lyrics, and he certainly disavows the entire spectrum of political labels foisted upon him following 2112: “I like noble virtues, the difference between right and wrong. I also don’t like people telling me what to do. … You have to make your own decisions if you want your ideals to come across. … I’m against socialism because again it stifles the individual. It tries to wrap him up not letting him think for himself.”

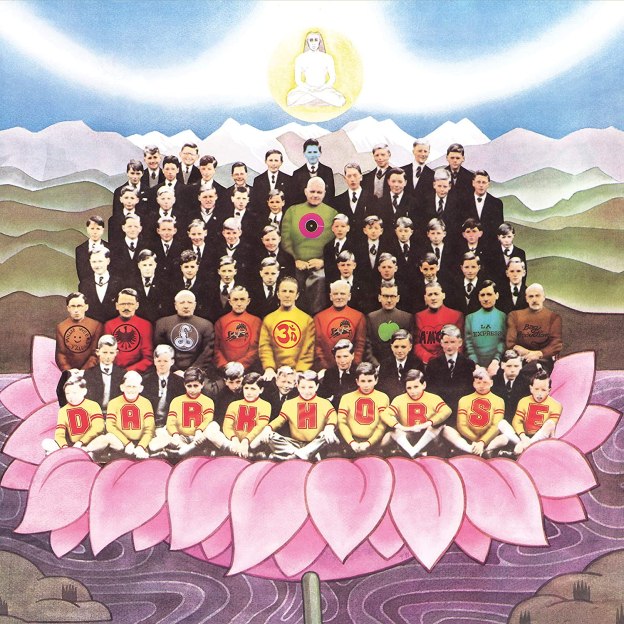

Most see the story of 2112 influenced by Anthem, and Birzer adds Zamyatin’s We. For Peart, the story of individuality and freedom triumphing over repressive government (especially religious oppression) is represented by what Popoff calls “the lurid red pentagram,” which “had nothing to do with Satan, representing instead the creativity-suffocating authorities of the tension-filled tale,” with the naked fellow representing man at his most basic, most needy, ready for something new. 2112’s ending is usually interpreted optimistically, which is fitting for how successful the band came following the album’s reception among the people who actually paid to listen to the album, the fans.

All the Same We Take Our Chances: A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres

As the ’70s and prog rock were (semi-)officially ending, Rush took the lessons and successes of recent albums and, in a sense, doubled-down with effectively a double album spread out over a couple of years. Continuing the pervasive Rush themes of anti-authoritarianism found in “Bastille Day,” “Anthem,” and many more (and after), the title track of A Farewell to Kings clears up any doubt listeners may have whether “2112” was about exchanging one oppressive government for another. As good as the opening track is, and Rush was always good at setting the tone of their albums with the opening tracks, the real treat of the album is “Xanadu,” the longest non-side-length song in their canon except “Necromancer,” and it is undoubtedly a much better song than “Necromancer.” This is not to say the source material, Coleridge’s “Kublai Khan” is better than Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, of course; rather, the band has simply matured in all facets of their musical craft.

“Closer to the Heart,” fan-favorite and the closest Rush gets to a traditional pop-rock radio-friendly hit, echoes lyrics and sentiment from the opening track; “Cinderella Man,” another optimistic anthropological song from Lee, is based on the Frank Capra movie Mr. Deeds Goes to Town; and “Madrigal” is effectively Rush’s last “medieval prog rock” song, with their own twist. The close of the album is, of course, the first half of Cygnus X-1, “The Voyage.” The music of this half is likely more memorable than the lyrics, the opposite being true of book two kicking off Hemispheres.

Cygnus X-1 together is the longest Rush story except for Clockwork Angels, their grand finale, with the diverse four-part “Fear Trilogy” a close second. As with the odd pairing of Rand and Tolkien on Fly By Night, Cygnus X-1 pairs Cervantes and Nietzsche. The vehicle the traveler uses to embark his mission is the Rocinante, like Don Quixote’s steed; and the gods at war in book two are Apollo and Dionysus. Birzer quotes Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy at length, as well as interviews from Peart indicating his affinity and lifelong commitment to a Nietzschean philosophy. The conclusion of the epic is that logic and love must join together in a “perfect sphere” to unite both heart and mind (as well as god and man) in perfect balance.

The second half of the album (it is difficult for me to think of it as the “second side,” considering I first heard most Rush albums on compact disc) is another disparate collection of quintessential Rush: Peart autobiography in “Circumstances,” tongue-in-cheek political satire in “The Trees,” and virtuoso playing in the band’s first instrumental, “La Villa Strangiato.” Surely most Rush fans wished the boys had indulged in more “exercises in self-indulgence,” as its subtitle jokingly calls it.

Everybody Got to Elevate From the Norm: Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures

If 2023 has taught us anything in the music world, it is that fans should “never say ‘never’”; a year that saw new releases from the Rolling Stones and Beatles should show us that even though Neil Peart is no longer with us and Rush officially disbanded five years ago, one should never give up hope. I say that mainly for myself, as I was originally planning on opening this final section with “Now that the Rush corpus is completed” – but “never say ‘never.’” With the Rush corpus (temporarily) completed, fans tend to categorize their output in different ways, often by year, by major sound style, or by subject matter. Birzer, like most, posits Rush as its own entity, then collates the remaining ’70s albums together, most of the ’80s albums together except for Presto, joining it to Roll the Bones and Counterparts, leaves Test for Echo as its own era, and, understandably, unites the remaining Rush albums following Peart’s hiatus and personal rebirth into one final group. Though it is not a matter worth much debate, I disagree mildly concerning the ’80s albums: I posit Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures should go with the earlier albums as the culmination of the band’s mainline prog era (as I did here for this paper), and Signals through Hold Your Fire is the band’s “second wave style” of prog, much like Tull’s folk trilogy is still prog rock but of a different kind than the more obvious concept albums from Thick as a Brick through Too Old. I agree that these ’80s albums are united in their clever multi-layered album titles, but musically the first two seem different (maybe it is just the synthesizer that defines the era for me). Rush’s Presto does feel like it is cut from a different cloth than the rest of the decade’s material, indeed.

Forgive me if this leans into hyperbole, but the opening of Permanent Waves is possibly the most invigorating opening to any rock album of all time. The audience reaction in every live album since 1980 should be proof enough. Though many paeans to the radio are at times tongue-in-cheek, like “The Spirit of Radio” here, Queen’s “Radio Ga Ga” for another example, at the heart of them is an unconquerable optimism despite the growing commercialism that is often noted for ending Prog rock and the “glory days” of the ’60-’70s music scene. Peart ends this with a clever, if not wistful, updating of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sounds of Silence,” itself a critique of the growing commercialism of society and the music industry fifteen-some years earlier (from Peart’s perspective).

The album continues Peart’s lifelong agon with religion in “Freewill,” which also incorporates Peart’s readings of Jung. Oddly, though not so odd considering Peart’s penchant for unusual pairings, the album follows this with “Jacob’s Ladder,” which is clearly an Old Testament allusion (which Peart surely knows). Lyrically, the song is ambiguous enough to forestall outright antagonism to religion, but it does lean toward a more humanistic solution to wisdom-seeking. Perhaps “Babel” would have been a better title, but Peart likely knew that “story” ended in confusion.

“Entre Nous” may be influenced by The Fountainhead, or perhaps Peart’s love of reading in general, as the second line “Each one’s life a novel” may imply. One could have wished Peart had taken this open-minded approach to religious ideas (and people) more, but such is life. “Different Strings” continues the same theme of “Entre Nous,” though it ends with Peart’s standby atheism: “All there really is: the two of us.” “Natural Science” began life as a musical adaptation of “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” but Peart found it too out of place with the general theme of the album, and while that does not do this paper any good, it certainly served the album well to shift into the song’s eventual tripartite exploration of nature, science, and integrity.

Moving Pictures opens with perhaps Rush’s most beloved song, and another eventual encore staple that always brought cheers from the audience, in “Tom Sawyer,” whose literary influences should go without saying. It is fitting for this song to be, if you will allow the expression, the real “anthem” for Rush, a band whose “mind is not for rent / To any god or government / Always hopeful yet discontent / [Who] knows changes aren’t permanent / But change is.” Surely that encapsulates what Rush was about: literary-influenced individualism.

“Red Barchetta” was inspired “by a 1973 short story by Richard Foster” entitled “A Nice Morning Drive,” though Peart changed the type of car from the story. Peart has discussed it in multiple interviews, even meeting the author toward the end of his (Peart’s) life. “YYZ” is another masterful instrumental, and “Limelight” is another Peart autobiographical song, somewhat ironically making him and the band even more famous from the rousing success of this, perhaps their greatest album. The song lyrically anticipates the next song, “The Camera Eye,” and reflects on the live album released after 2112, All the World’s a Stage and the Bard’s famous line from As You Like It.

Birzer describes “The Camera Eye” as “a John Dos Passosesque view of two cities, New York’s Manhattan and London,” which Peart mentions in bonus material on the 2112 blu-ray release. It is certainly the last long song of Rush’s career (to date). “Witch Hunt,” he says, was inspired by Clark’s The Ox-Bow Incident, which seems feasible enough. “Vital Signs” is a preview of the more synthesizer/technological sounds coming in the heart of Rush’s ’80s output, which is likely why Birzer links Signals to these two albums. Perhaps it is fitting to end our examination of Rush’s literary-influenced prog phase of their career with “Vital Signs,” as Peart says “Leave out the fiction.” Coincidence, perhaps, but the band does shift into different directions, though they never stay away from Peart’s reading-inspired lyrics for long.

After quoting interviews in which Peart mentioned Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Hemingway, Dickens, Hardy, TS Eliot, and Frost, Birzer lists several other authors mentioned by Peart and others in interviews and other places throughout Rush’s career: Hawthorne, Melville, Henry James, Wilkie Collins, Wilde, Woolf, Sinclair Lewis, Dreiser, Cather, Edward Abbey, Fitzgerald, Lieber, CS Lewis, Pirsig, Stegner, Pynchon, Barth, Tom Robbins, and Kevin J. Anderson. Surely this list is inexhaustive. Though perhaps we could have wished he spent more time with authors before the nineteenth century, especially more Christian authors like Eliot and Lewis, Neil Peart, like Tony Banks and Peter Gabriel in Genesis, is a resplendent proof for our quest for literary influences on the lyrics of prog rock. Surely much of the timeless quality of Rush’s output, much of what helped them to “elevate from the norm” of an already markedly intellectual musical genre, is Neil Peart’s adult lifetime of reading almost every genre from poetry to fiction to philosophy, a lifetime of reading reflected in his eye and in his lyrics.

Bibliography

Birzer, Bradley J. Neil Peart: Cultural Repercussions. WordFire Press, revised 2nd ed., 2022.

Popoff, Martin. Anthem: Rush in the ’70s. ECW Press, 2020.Weigel, David. The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Progressive Rock. New York: Norton, 2017.