Christopher Rush

Don’t get me wrong: I enjoy being a teacher. But we all enjoy a break from the rigors of academic life once in a while, and since the end-of-the-calendar year holidays are especially enjoyable, spending them at home away is always the way to go, if it can happen. Certainly we at Redeeming Pandora are grateful for and to the men and women in the armed services who spend the holidays (and months of the year and more) away from home, oftentimes in dangerous situations. Being a teacher has never yielded challenges such as those, no matter how much we may rail against certain excursions into the backwaters (or floodwaters) of rural Chesapeake. So I hope I have a proper perspective on the extremely blessed life I have lived, especially having usually been able to enjoy several weeks off each year during the holidays. Sure, some years have been better than others, but we all experience that.

We’ve covered just about every subject by now in these holiday tradition articles, so it may be about time next year to revisit some old topics and see how life and things have changed over the years (when we began this enterprise, my wife and I had a four-month-old daughter — now we have a seven-year-old daughter and a five-year-old son, so some things have changed indeed). For now, I’d like to wrap up 2016, a challenging year for a lot of people for a variety of reasons (some of them even real), with a few thoughts on one of my favorite holiday traditions: playing video games for hours and hours and hours and hours.

I believe I have mentioned once upon a time there was a decently-sized stretch of holiday vacations in which I played Illusion of Gaia to its completion on Christmas Eve. The tradition started even before that with annual year-end plays of StarTropics. Some of the best Christmas breaks, though, featured lengthy plays of my favorite video game of all time, Final Fantasy VI. Some day soon I’d like to get back into that game, but first I have an obligation to my children to finish ChronoTrigger. We started that a year ago, but things and time and such got away from us this summer, so I still have to finish that up. In recent Christmas breaks, I’ve been playing more PS3 games, such as the Uncharted and God of War series (nothing says Christmas in this day and age like slaughtering Greek gods). Some of the Batman Arkham series have also started to associate themselves with Christmastime. Two main reasons explain this phenomenon: Christmastime is one of the few times of the year in which I have the freedom (and life energy) to play videogames; also, popular videogames get very inexpensive if you wait a year or two after their release, and thus make excellent stocking stuffers, and what would Christmas be without playing with your new toys/games?

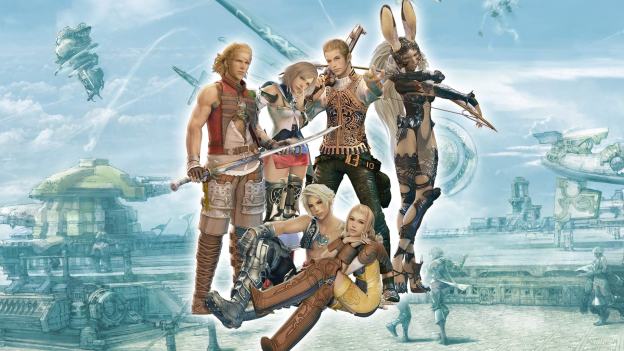

Moments ago I mentioned I didn’t complete ChronoTrigger this past summer with my kids (I do most of the playing, they sit back and enjoy the story; it works out well for everyone, really). This was because I got distracted by another trip down memory lane, which happens to be the main subject of this oddly-themed Christmas article: Final Fantasy XII.

FFXII is at worst my third-favorite game, behind FFVI and ChronoTrigger, and it has been making some ground on ChronoTrigger. I admit I have not completed the entire game, though I have spent a fair amount of time playing it (over 130 hours, if the internal chronometer is to be believed), but I have played enough to get a good understanding of it. I played it shortly after it first came out, a decade ago, but somehow life’s circumstances took me away before I could make it all the way to the end (I suspect our move from Virginia Beach had something to do with it). For some time, I had a desire to get back into it, and this past summer I just decided to go for it. And that’s mostly how I spent my summer vacation, and, hopefully, a fair amount of my Christmas vacation.

The Story

You know I wouldn’t spoil anything without warning you in advance, but one of the benefits of not knowing the ending myself is I can’t tell you about it, so I will focus on the basics. FFXII takes place on the world of Ivalice, possibly the most fully-realized world in Final Fantasy history, in that it has a rich, noticeable history and a palpable present, with all nations and races full and developed and interactive. Even the great FFVI suffers in this respect at times: you’ll show up in a new part of the world because the game wants to introduce a new character, not because this location has a meaningful connection to the places you’ve already been. This is not so in FFXII: all races, all nations, all cities are aware of the others — they don’t always get along, of course, but the world is connected very cohesively.

Ivalice, like all worlds, has various nations, some of which prefer to have more international political power than others. The Archadian Empire has fallen into unscrupulous hands, and it is starting to gobble up surrounding nations. The Rozarrian Empire on the other side of the world is not terribly happy with that. Caught in the middle of these two war-impending empires is the Resistance. This is basically where our heroes come in. Various survivors of previous wars and insurrections (and other economic considerations) have banded together to reclaim what was once theirs, to fight for the freedom of the people, and to make the world a safe place of justice and freedom once again. The usual stuff of great stories.

What makes FFXII different, though, from the typical rebels vs. empire stories is both how unobtrusive this main storyline is to the playing of the game as well as the very engaging past of the world, as our heroes spend a good deal of their time learning about the past and its relics to understand present-day conflicts and solutions (it’s a great lesson for us today, as well).

I say the main storyline is unobtrusive, but I don’t mean it’s dull or short—only that you can enjoy playing this game for hours on end on enjoyable side-quests and level raising and whatnot and the game will not punish you for taking so long between plot points. Yes, there are important plot points and cut scenes and “once you do this you can never go back to how it was” events that change the game, but the game gives you plenty of warning and opportunity to commit to them or come back later if you need to raise levels, upgrade weapons and armor, restock your provisions, or whatever. You do need to advance the story some times to get access to the better equipment and spells and things, but by that point in the game, you’re ready and eager for it, anyway.

Magic is a key part of all Final Fantasy games, but one of the reasons I like FFVI so much is the significant magic vs. technology subplot. It’s not just conjuring up dark spirits to tamper in God’s domain. Similarly, FFXII takes the idea of magic and connects it to technology and supernatural forces, but one is never given the impression your spells are aligning you with the forces of darkness. The more you learn about your world’s past, and the forces that have shaped it for good and ill, the more your understanding of the supernatural and magic grows (always a good thing). The game doesn’t give you the impression the divine is just aliens you can control or conquer — in fact, the many characters of religious faith are presented in the best light as anyone in the game.

On the journey to gather allies, learn about the world, and attempt to stop a war before it destroys the world, our heroes find out some forces within the Archadian Empire are also working toward peace — but other forces are working to make the magic even more dangerous (thanks to technology), and we must take a more active role in the conflict for the slam-bang finish. That’s where I am in the game: a few events away from the finish. I’ll let you know how it goes (I hope).

The Characters

Once you get past a brief introductory scene that familiarizes you to the game mechanics and a bit of the backstory to the main conflicts involved, the game begins with our main character, Vaan, a refugee street urchin working odd jobs for a local merchant with big dreams of becoming a sky pirate (like a regular pirate, but on a flying airship). He has a lot of anger inside because of the losses he has suffered at the hands of the Archadian Empire, but on the whole he is an optimistic, energetic young guy who wants to see the world, treat people well, and learn (though he’s not yet so mature he knows it’s impolite to ask a woman her age). Even though Vaan has some significant connections to the major conflicts of the overarching story, he acts mostly as our advocate in the world, observing and learning, with little direct involvement in the present storyline itself (sort of like Nick Carroway in The Great Gatsby).

Vaan’s street urchin friend Penelo is the first other main character we meet once the present storyline begins, though she is the last to join the group. She, too, has suffered because of the Archadian Empire, but she, too, tries to keep her spirits up even in these troubled times. Part of the reason even the homeless are chipper at the start of the game is because the Empire hasn’t shown its true colors yet and material prosperity seems to be back again (odd how people are quick to ignore political morasses when personal economy seems healthy). Regardless, Penelo vows to keep her eye on her good friend Vaan for his own good. You’d think there’d be a bigger love interest story with these two, but there isn’t (and that’s not so bad).

The main story of our heroic rebels actually centers on Ashe (short for Ashelia), the young princess of our country Dalmasca who is leading the Resistance in disguise. It is her role to travel through the world, learn about her heritage and connection to the magical forces at work in the world (in her effort to destroy all magic once and for all), and restore Dalmasca’s freedom from the Empire (with or without destroying the Empire in the process). Her dominance in the ongoing storyline lends one to think of her as the main character instead of Vaan, but don’t let that bother you. Instead, think of it as a clever element of the game to give all the main group members a significant amount of screen time.

The brawn of the group is another loyal son of Dalmasca, Basch. We actually meet him in the prologue scenario, in which it seems his loyalty is a sham, but that is cleared up within about twenty minutes of playing the game, so I’m not spoiling anything, really. Plus, since he’s on the cover with all the other heroes, you know he’s got to be a good guy. He, too, has strong connections to the Empire and the overarching stories. Suffice it to say, despite his potential loyalty conflicts (I don’t want to spoil things for you, but let’s just say he has a brother who’s a high-ranking official for the Empire), he is a key member of the team, especially as his knowledge and experience guide the group during many side quests and even main plot events. Plus, as I said, he’s really strong against non-magical monsters, so giving him a war hammer or heavy axe and letting him have at it is pretty fun to watch.

Rounding out our main group (a comparatively miniscule group of six heroes, contrasted to the cast of fourteen in FFVI), we have a pair of real-life sky pirates: Balthier and Fran. Fran is a Viera (basically, a race of human-looking aliens … with bunny ears — but it looks far less silly than it sounds, believe me), and as such she has a strong connection to the magical elements of the world (called Mist), which makes her a strong magic user, though she’s also good with a bow. Balthier and Fran are basically the Han and Chewie of the team, if that helps, and, like Han, Balthier thinks he is the leading man of the story, adding a rather humorous element to a number of cut scenes and character interactions (and a lot of people seem to believe him, since Vaan oftentimes takes a narrative backseat to the other characters on the team). Balthier, too, has a strong connection to the Empire that causes him a good deal of pain, which he usually glosses over with charm and skillfully deflecting our attention to other things. He wants us to think he’s only helping the Resistance for the potential reward Ashe will give him when she regains her throne, but there’s more to it than that (yes, it’s that old story, but it comes off with enough differences that it’s not just a banal Star Wars rip-off). Fran, likewise, has outsider issues, being far from home and her race and having spent possibly too much time with the humans (“humes” in this game). I know that, too, sounds awfully familiar, but the game presents her character conflicts in fresh ways, even with the archetypal aspects to it all.

Along the way, our heroes gain temporary allies, travel the world, gain levels, make friends, restore order, learn lessons, raise levels, buy items, locate runaway cockatrices, save the world (I assume) and so much more. With a small cast of main characters this time, combined with the still-impressive cut screen (in-game movies) technology and voice acting, we really get to spend a good deal of time getting to know them, see them interact (which is usually the highlight of games and stories and such as this), and connect with them in multiple ways like any good characters from “literature.” Just because these characters and their story are in a video game does not make them any less meaningful or engaging as Hamlet or Walter Lee Younger or Nora Helmer or Anna Karenina or any of the highbrow gang. They are just as real, too. You can scoff, sure; I can take it. But if we live in a world that tells us people who transport a ball of air around a hardwood court or grass yard are heroes to be followed and emulated and lauded (and financially supported), I think it’s fair to say characters in a game with meaningful conflicts and needs and hopes and heartaches and dreams that resonate within us, characters with which we have a direct involvement through our decisions as game players, are just as real as literary heroes, historical heroes, and athletic heroes. And I know I’m not the only one who thinks that way. Plus, I’m a published author. You can trust me.

The Distinctives

So what’s so special about FFXII? How can you play for hours and hours without advancing the story (and have fun doing it, more than just the RPG-requisite level raising)? Here are just a few of the many enjoyable aspects of FFXII that make for a great holiday (or summertime) vacation pastime.

The Gambit System — in most videogame role-playing games, you have to manually tell all your characters what to do during every encounter: you fight that monster, you cast that spell, you use that item, round after round after round. FFXII does away with all that button pushing with the clever gambit system: dozens and dozens of context-sensitive commands you can “pre-program” for your characters to handle virtually all encounters without you having to tell them what to do every single time. Once you get the hang of it, it becomes a real time and thumb saver. You’ll be tinkering with and adjusting it throughout the game, plus you’ll be telling your characters what to do plenty, so there’s no loss of interactivity or feeling of control/guidance of these characters. All that’s lost is the repetitive nonsense.

The Battle System — unlike most RPGs that feature random encounters with monsters to give you experience (to raise levels and attributes and whatnot) and money (to buy new armor, weapons, items, etc.), FFXII gives us the “open world” feeling of seeing where all the enemies are, just like you are there in the plains, on the mountain path, in the castle, or wherever you are — you can actually see where the enemies/monsters are in the world. This makes so much more sense, and combined with the gambit system, you can have fun raising levels by running around the world, watching your heroes act and react naturally, all the while enjoying the fantastic musical score by Hitoshi Sakimoto (seriously, many of the themes of the soundtrack are gorgeous aural experiences). Additionally, unlike the usual “you get 287 gold pieces for defeating those blue slimes” (as if monsters would carry human currency), FFXII eliminates that thematic discrepancy by having you pick up “loot” from the foes you defeat:, loot that makes sense: wolves drop pelts, for example; bats drop fangs; skeletons drop bones and iron swords they were carrying. You, then, take the loot you pick up from your fallen foe (just like epic heroes) and sell it all back in towns for money, which you can use to buy what you need from other shops. Plus, the game has bonuses for fighting similar kinds of monsters, developing “battle chains” that can result in better and better loot as you take the time to stay and fight and raise levels — the game rewards you in many ways for doing what the game effectively requires you to do, making the gameplay experience that much more enjoyable. Plus plus, it makes a lot more thematic sense.

Crystals, Travel, and Non-linearity — as convenient as it used to be in older Final Fantasy games to be able to save your game practically anywhere in the world (other than in dungeons or in the middle of certain levels or areas except for special save spots), the hassle of having to buy cabins or tents or staying at inns sometimes meant a good deal of precious gold pieces going to that. The save crystals in FFXII eliminate that problem (I know earlier entries in the series use similar objects, like FFX, but they make better sense in FFXII). True, you don’t get some of the great nighttime dream sequences or cut scenes like in FFVI, but that’s a small price to pay for not having a price to pay.

Another convenience of certain save spot crystals in FFXII indeed are the orange transport crystals that allow you to instantaneously travel to various parts of the world you’ve been to before in the game, at the small cost of one teleport crystal. These don’t cost very much gp, and soon enough in the game you’ll have acquired so many of them anyway through picking up loot from fallen monsters, rewards for special tasks you accomplish, and other events in the game you may likely go through the whole game without paying for a single transportation crystal. As much as I love FFVI (and IV), so much of the first part of the game is a niggling feeling of “boy, when I get my airship, I’ll be able to go anywhere, do anything…” and suddenly you realize you are exactly like Vaan in FFXII, waiting for the freedom of travel. The teleport crystals in FFXII eliminate that feeling of impatience and limitation almost immediately in the game (which is like, thirty minutes of game time, small potatoes considering how long you will be playing it). You’d think you’d have Balthier and Fran’s airship early in the game when they join the party permanently, but events in the game damage the ship so you are on foot for most of the game. This does require you to walk through large sections of the world until you get to the various teleport crystals, but this is more beneficial for you, since it gives you the opportunity to fight monsters, gain experience, gain loot, raise levels (all the nitty gritty of classic RPGs, though made more fun be all the developments enumerated above).

These teleport crystals are possibly the key enabler of freedom from the main story. I mentioned earlier the story is fairly unobtrusive for most of the game, and this is true depending on how you play Final Fantasy XII. With the teleport crystals, you can easily leave the main palace or dungeon or next key plot point before you enter it, transport yourself somewhere else in the world, and spend hours doing sidequests or level raising or whatever, then teleport back to where the game “wants” you to be without any of the AI characters any wiser or frustrated at your “dilatory” behavior. That is true freedom you want in a game like this.

Growth — raising levels is considered by some jackanapes a “necessary evil” of RPGs: as the game progresses, the enemies get harder, you have to get stronger, faster, you need more hit points, more magic points, et cetera et cetera et cetera. These same Tom Fool wastrels use unkind words to describe the process of raising levels, fighting monsters somewhat mindlessly for hours on end solely to gain experience and dosh to get your characters stronger and buy them better stuff. I admit, for most RPGs, the process of gaining levels can be somewhat tedious, but as we have already indicated, that does not apply to FFXII. The background music, the gambit system, the onscreen encounters all add up to the most enjoyable level-raising experiences in RPGs (surpassing even FFVI in this respect, yes). But that’s not the point here. The point here is in addition to all that, level raising in FFXII is more than just getting your characters to their programmed maximum attributes: similar to (but improved from) FFX’s “sphere grid” system, FFXII uses the “license board” to allow you to customize each character. You decide what spells they learn, what weapons they can use, what armor they can use, and other customizable elements. As indicated above, some characters are naturally better at some skills than others (Ashe and Fran, for example, are naturally better at spellcasting than Balthier and Basch, say, and it’s wise to give them some spell gambits, especially as their healing spells are more effective than, say, Vaan’s). This licensing board system gives you great freedom (that word again) to customize the characters differently each time you play the game. As I said, I like to give Basch a war hammer or battle axe and let him smash opponents. Penelo is “supposed” to stay back and hurl spells or long-range weapons, but she’s a tough, fast kid, so I like to give her strong spears or poles to jump into the fray. Balthier’s guns are strong, but I prefer to give him a katana or other ninja blades and give him accessories that allow him to strike multiple times per turn. The game gives you far more options than these.

Side quests — the meat and potatoes of the game’s freedom and fun come from the side quests. I told you there’s a point in the game in which you travel the world looking for runaway cockatrices. That’s just one of literally dozens of optional side quests available throughout the game. You can get a fishing rod and learn how to fish for as long as you want. In addition, the more you engage with the characters (regular townspeople and the like), the more the game rewards you. Even these people are realized characters who change and are aware of the main events of the story, and when you encounter them in seemingly throwaway moments, you will meet them again in another part of the world, and frankly, that’s awesome. I don’t want to spoil too much of the rest of the game for you, but suffice it to say this game gives you plenty of reasons to play it for a long, long time.

Hold on, let me tell you perhaps the most clever side quest: the Hunts. You have to join it early in the game as a required plot point, but after that early incident the rest is optional. The Hunts are this terribly clever side quest that lasts the whole game in which various citizens of the world are having various problems (a huge snake is preventing a spice trader from importing his goods here, a young child’s pet turtle has somehow transmogrified into a giant snapping turtle of destruction there — you get the idea), and only you and your friends are up to the task of setting this fiasco right again. It’s a great way to earn unique items (for some things, the only way to earn rare items), travel familiar territory for new purposes, and just have fun, as each hunt has different requirements and aspects to it (they aren’t just “go here and beat up this thing and come back for your reward”).

But it gets better. Once you start making a name for yourself as a great hunter, you get to join the clan of fellow hunters, which enables you to get other nice treats, info on elite marks, and gives more cohesion to the world. Later in the game, you get the chance to join a second, more elite Hunt Club, in which ultra-rare monsters appear only during these hunts throughout the world, enabling you to get more elite items. Yes, sometimes these hunts can be devastating if you aren’t prepared or playing wisely (which may have happened to me a couple times this past summer), but that can be true of the main game as well. This massive, complex but not complicated series of side quests is just one of the many clever ways this game presents a unified, believable world from beginning to (I assume) end.

The important thing about the many and varied side quests throughout FFXII is not that they are basically “necessary” to get the good stuff to win the game. You can play through the main storyline just fine without any of these optional elements, and that will be a rich, rewarding experience all its own. Yet, the greatness that is the side quests of FFXII lies also in how much they reward you playing them. They give you great stuff, sure, but that alone would be meaningless if they weren’t as fun as they are. I said before they make the supporting characters you meet somewhat incidentally come alive more meaningfully, and that point should not be ignored. Without descending into sounding maudlin, the characters (main and supporting) and the side quests really make you want to spend time in this world. Yes, the world has a lot of problems (impending war, gigantic monsters that want to destroy you, crumbling ruins of forgotten technology and civilizations, alien beings trying to pull the strings on the development of all races, the usual), but like the opening song to Deep Space Nine or Star Wars, you just get overwhelmed with the feeling of “yeah, I want to be here for a while.” And the side quests especially allow you to do that in meaningful, enriching ways.

The Goods

No, it’s not “just a videogame.” Like the great works of art and literature, Final Fantasy XII causes us to look within and around and make ourselves and our world better. That’s what Christmas is partly about as well, isn’t it?

And, man, that musical score….

I’m very glad Christmas break is almost upon us again. I really want to get back to Ivalice and play more Final Fantasy XII. If you don’t have a PS2 (did I mention it is a PS2 game?), do not fear. Just in time for its 11th anniversary, I hear a remastered version is coming in 2017 to the PS4 (you have one of those, right?), complete with an even better licensing/customizing experience. If they keep the music and characters and story and other side quests in place yet improved with modern technology and whatnot, you will find this a fantastic experience.

Have a Merry Christmas 2016, everyone! Even if you don’t get around to playing Final Fantasy XII, we at Redeeming Pandora hope it will be a refreshing, leisure-filled time of quality family experiences, meaningful spiritual reflection and growth, musical memories old and new, tasty treats and savory snacks, nostalgic films, games and fun and shopping and games, and many, many days of lounging around at home for the holidays (preferably in your jimjams all day long — that’s my plan).

See you in 2017!