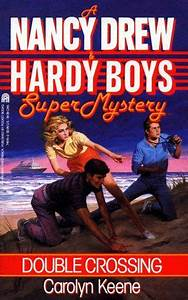

Nancy Drew! The Hardy Boys! But mostly Nancy Drew! It really is mostly Nancy’s story, with the occasional visit from Frank and Joe, who are concerned with their own side-mystery for most of the story. Nancy is trying to enjoy a little vacation with her buddy on a cruise ship, but suddenly your typical American CIA-kid snob clique shows up and spoils the whole thing, what with their espionage, treason, murder, and the usual CIA-kid snob clique shenanigans. I haven’t read a lot of either Nancy Drew or Hardy Boys adventures (I was mainly a 3 Investigators guy growing up), but this does bring an immediate since of much-welcome nostalgia. Sure, there is mayhem and murder and other unpleasant things (with a bizarre undercurrent of romantic flirtation between Nancy and Frank, despite her immediate commitment to put the kibosh on that … until the next chapter), but this takes us back to the good ol’ ’80s spy adventures of Remington Steele, Scarecrow and Mrs. King, and the like. It was a good time, and this “super mystery” (not all that much of a mystery, really, since the author gives us enough obvious clues and red herrings throughout so we can figure it out fairly easily) sends us back there for a good romp. Though, we are left wondering why Nancy keeps allowing herself to get trapped, bamboozled, and tricked at the end of every chapter.

The title of this book, combined with the early protagonist characterization of Agatha Raisin starting to read lots of Agatha Christie novels, lends one to think this is going to be a humorous spoof romp of a mystery, filled with Magnum-like winks to the audience, classic mystery callbacks, quirky sidekicks and townsfolk, and a whole lot of fun.

That’s not what this book is, however. Agatha Raisin is rather petulant, cranky, and self-centered, despite her purported attempts at self-improvement. Roy, the former employee-turned-periodic sidekick/plot catalyst, seems like he is going to become a fun and helpful foil, but he ends up being a self-serving potty-mouthed jerk. The idyllic townsfolk are somewhat helpful and kind — disappointingly, Ms. Beaton makes the village parson the meanest hypocritical jerk of the regular community, not including the “townies” element.

Yet, one must be patient. The poor lady (our “hero”) has just ended a rather long span of her life and is trying to begin a new life, and it sort of looks like she accidentally killed a beloved neighbor guy her first week of her new life, so getting to know people and secure a fresh start is rather challenging. Plus, the first book of a new series is always a bit of a jumble. Fer-de-Lance is certainly not the most enjoyable Nero Wolfe adventure. Thus, if Ms. Beaton tones down the “see how I am suffusing this book with authentic directions and topography because I live there?” descriptions, tones down the unnecessary saltiness, and increases the light attitude the title and heroine’s name intimate, this series may become something interesting. (Since I know there are 20-some entries in the series by now, apparently some people think this character is worth treasuring.)

Another “Archie has to move to a client’s home to do inside investigation story,” this has a bit more to it than some of the others in that Wolfe sub-genre, though at times it does suffer from that sub-genre’s middle-slowdown pacing. The “extra” this one has is mostly at the beginning, with the very humorous clash between Archie and Wolfe about Archie even taking the case or not, eventually leading into Wolfe getting dragged further and further into a case he never wanted in the first place. Another twist is the client is absolutely sure who the guilty party is and insists Archie finds the proof. Naturally, Archie is opposed to this sort of thing, and his personal quest becomes another strange layer of “proving the client wrong” — a client he, too, is not keen on but got mostly to get Wolfe’s goat. Archie investigates the only likely group of suspects in the case, stumbling accidentally onto the title, a line of poetry written years ago by one of the suspects (a mostly unrelated expression at the time of its arrival, considering the crime Archie is investigating is insider trading having nothing to do with death). The case takes menacing and deadly turns, eventually, and Wolfe is dragged fully into it, leaving us guessing the identity of the guilty party (or parties?) more so than usual. Not too shabby, despite the slowdown in the middle.

So mostly fantasy, mystery, some kid books, and a teensy-weensy bit of grown-up history — basically, the book version of the other list I did in this issue. Ah, well. C’est moi. In any event, it’s very nice to be back with you again, friends! See you at Christmas!

I’ll go with 2.5 stars rounded up, how’s that. I’m not really sure I “liked it,” since there is very little content in here (including characters) we are really supposed to “like” in any traditional sense. As the high-school toddlers who recommended (and leant) it to me warned me at the outset, “all the characters take turns playing the bad guys.” And by jingo, they were right. Sure, you may say this is more “realistic and gritty” for a medieval-fantasy-type story, when life is hard and smelly and morals are subsumed under survival. That’s fine. This is a “grown-up” fantasy.

My two main issues, apart from the gratuitous stuff (which is likely the main reason why it is popular on television), are 1) there’s no overt point — the characters are just doing their thing, living their lives, reacting to what has been decided around them. That may add to the “realism” of the world, but I can’t help but contrasting it with The Wheel of Time. That series is much different, and I like it better for those differences: there is a goal, the story is heading somewhere intentionally (even if at a languorously snail’s-crawl pace) — there is a clear “bad side.” The “good side” of TWoT is not so straightforward, so I’m not necessarily faulting GoT for not having “pristine, angelic-like John Wayneish heroes.” TWoT has flawed, “shades of grey” heroes all over the place, possibly just as “Biblically unmoral” as GoT (though much less explicit about it).

Perhaps you’ll say “oh, there’s definitely a point to GoT: Dany is going to reconquer the Seven Kingdoms, marry Jon Snow, destroy the Lannisters, raise Tyrion as Ruler of Everything Else” and all sorts of other stuff only you know about having seen/read beyond book 1. Well, maybe. But I don’t get any of that sense from the book itself. Things just happen. Which leads us to my 2nd issue.

2) most of the book is reaction, not action. Yes, a few key things happen “on screen” (still talking about narrative focus in the novel), but so much of the book is just “apparently some time has passed, and here’s what they are thinking about now.” The passage of time is horribly haphazard, it seems to me (perhaps Mr. Martin has everything calendared out, which would be swell). We get hundreds of pages setting up to Ned Stark’s climax … and it barely is mentioned indirectly when Arya is sort of not looking. Out of seemingly nowhere, armies have started terrorizing the countryside … why, because Catelyn snatched up Tyrion? Is that why? A bit unclear, really. (Maybe I’m just a bad reader.) I understand this can be a fine way to move the story along without going over every single detail (in stark, so to speak, contrast with TWoT), but so much of the “action” in this novel was “reaction,” reaction to things we haven’t really experienced. Maybe you real fans like that; I found it a bit niggling. That’s me. I’m probably wrong. I’ll keep reading the series, though, mainly to see how it ends, I guess (I hear some unspeakably grotesque things will happen soon, so we’ll talk about that when I get there).

Continuing shortly from A Game of Thrones, A Clash of Kings broadens both the character base and geographic areas of Westeros. New characters such as Stannis Baratheon, Davos Seaworth, and Brienne of Tarth give us more people to actually root for (well, maybe not Stannis) in an otherwise grim and unfriendly land. The Starks continue to encounter nothing but problems: Arya is trapped between King’s Landing and Winterfell, Sansa is trapped in King’s Landing, Robb is doing his thing (he spends almost no time in the forefront of the action in this book), Bran is still crippled though gaining special dream powers, Rickon is still a whiny baby, Jon is still unsure of himself in the wintry regions beyond the Wall, and Catelyn is still choosing to be with her father instead of returning to be with her own helpless children. Meanwhile, things aren’t going much better for Tyrion, even though he has a great deal of power and influence now. Since no one trusts him or credits him, everything he does to save the situation for his family and the city is largely ignored. Daenerys is still over in the sands, trying to find passage to Westeros. The only significant aspect of her storyline this book is the expansion of our understanding of the diverse cultures of Esteros. Other than that, her story is rather uninteresting this time around.

This second book still has the ubiquitous graphic content, no doubt for some sense of “authenticity” of this fantasy world in a sort of Late Middle Ages setting, but it’s not any more than the first book. It’s best to just skim/skip over that stuff and try to focus on what’s going on … which isn’t all that much. This is mostly a reorganizing of players and plots sort of book (until the slam-bang finish).

Like the first installment, a great deal happens between chapters, since we are given the limited perspective of a handful of characters who are usually away from the major events themselves. The “Clash of Kings” is a bit of a misnomer as well, unless by “clash” Mr. Martin means some sort of group, such as a “murder of crows” or “pride of lions.” There is certainly a brief “conference between kings” toward the middle, and a definite clash happens in the slam-bang finish, but it’s not really between kings. Even so, the general story does get a bit more interesting thanks mainly to the new characters. The aftereffects of the poor decisions in the first book continue to resound. Some mysteries are sort of explained, new possibilities for old characters are finally enabled, and desperate situations force our “heroes” into life-altering (again) situations, setting us up for a very exciting third installment.

Well, that was a bit of a roller coaster. I give it 4 stars not necessarily because I think it is a great book, but it is certainly superior to the first two in the series, acknowledging of course it does not have to do the same things the first two do and benefits from their scaffolding tremendously. Yet, Mr. Martin did not disappoint with that underpinning, which is why it deserves its merit on its own. Some people seem to revel in the “woah, I didn’t see that coming!” aspect of the series — though, taken literally, were that completely true, that would be a sign of poor writing on Mr. Martin’s part, so while most of the surprises are unexpected and we didn’t see them coming, the well-craftedness of them upon further reflection demonstrates them as wholly believable and consistent (even the last page, yes).

This book reminds us more than the first two Robb Stark is not a main character. At best, he is a supporting character. He never has any POV chapters, he spends almost no time “on stage” during Clash of Kings, he is always seen in relation to his mother (not a bad thing, but not a sign of his individuality or importance), and clearly he is young and makes mistakes — but when you are styling yourself as a king, making mistakes along the lines of betraying your most populous supporters is a really bad mistake to make.

Catelyn Stark, likewise, doesn’t seem terribly capable of making proper decisions either. She laments she is far from her two children who need her, acknowledges she doesn’t need to be with Robb, yet she doesn’t go back to protect Rickon and Bran and stays with Robb, effectively selfishly staying with her own father (for whom she does no good either) and away from her family who needs her. In other words, she’s not really any different from her sister. And she may be worse, since she makes almost all of it worse from what she did in book one to Tyrion.

Speaking of Tyrion, this guy really has a rough time in this book. We know he is the hero of the Battle of Blackwater and is effectively single-handedly responsible for saving King’s Landing, but no one else seems to. And things get worse for him throughout the book: everyone abandons him, people who know better allow their minds to be changed about him, and he is literally in the pits as the book closes, with him having lost just about everything.

Meanwhile, Dany has gained quit a bit … but her storyline is again wholly uninteresting and possibly less interesting than Bran’s storyline. She feels betrayed by practically everyone, becomes a misguided social justice warrior (not that I think freeing slaves is a bad idea, of course, just that she is easily distracted from her purpose without thinking through what the next step after freeing the people is — how will they live?), switches heroes, and effectively abandons her main goal by the end. The only good thing about her story is the reintroduction of a noble man we haven’t seen for a while.

Jon Snow does some things in this book as well. They are somewhat interesting and sad, as usual. Sansa is also in this book, mostly passive, as usual.

The new characters in this book are engaging (the new characters usually bring a vivacity to the new book), especially as we get a clearer pictures of the southern kingdoms around Highgarden and Dorne. Truly the highlight of this novel is the Adventures of Jaime and Brienne storyline. It is such an odd pairing but somehow Mr. Martin makes it work very well. The only bad part about it is it ends. Not only is it a very welcome addition to finally get inside the head of Jaime Lannister, but hearing from him what happened before the first novel began sheds some interesting light on these people and their recent history (which is still a bit confusing). Jaime, though, is also part of the saddest moment of the whole book, his final parting from Tyrion — this is such a disappointing moment for many reasons (which is probably why Mr. Martin wrote it the way he did). “Weren’t there other, sadder, more shocking moments in this book!?” you exclaim. Sure, sure, I suppose — but, frankly, none of them (by “them” we mean “deaths of seemingly major characters”) were all that surprising, and more frankly, some of them were rather welcome.

The other odd pairing is certainly Arya and Sandor Clegane, an odd couple that doesn’t have the same vivacity as the Jaime and Brienne Story, but it is much more interesting than, say, everything with Robb, Catelyn, and Sansa, that we are a bit sad when it ends, though glad Arya is finally going somewhere with the possibility of some meaning.

This book is replete with “so close”s — many of the characters who have been trying to reconnect with others are a gnat’s wing away in space and time from achieving some sort of positive reunion … but that’s not how Westeros operates. The spatial proximity is likely supposed to add to the bitterness within us when the planned salvation/reunion occurs, but by this time we have become so inured to it, most of them just end up being obvious foreshadowings of inevitable failures and (perhaps unintentionally) actually cushion the blows.

Let’s see, what else … oh, yes. Davos is in this one as well, being a great bulwark for morality and honor, having lost his “luck” in the Battle of Blackwater (and most of his children) but gaining perhaps a clearer vision of what is right and somehow presses that upon Stannis. Good for him.

We finally get a better look at Wildling life, which isn’t so bad, but discipline, it turns out, is indeed superior to sheer numbers after all (one of the few things Ned Stark seemed to get right). What we don’t get any good look at this time is the Iron Islands. In fact, Balon Greyjoy turns out to be truly the most disappointing facet of this book. Dany is likely the most dull, Jaime and Tyrion’s parting is the saddest, but the Balon Greyjoy facet is certainly the most disappointing.

On the positive side, this book clears up a few mysteries that have been hanging around from the beginning of book one, and we even get an eyebrow raising confession about the incident that started the whole thing even before book one, another of the “we didn’t see it coming … but we should have!” delicious twists. By the end of this book, we have the feeling it’s time for a whole new story. Major shifts have occurred for every major character/location, significant political events will drastically alter the direction of most nations and rulers, magic is increasing in potency, the Others are starting to make their move (though why that is we still have no idea), some wars are over but others are just beginning … the potential at the end of book two has certainly paid off rich dividends in book three, and now we are in for something very different indeed.

Oh, and then the epilogue happened … say what?!

Continuing the sensation of “the end is nigh but we have enough time to sail on ships for a few weeks,” The Fires of Heaven has very little to do with its title, but it does give us the impression things are burning, slowly in some parts of the world and quickly in others. For the first time, one of the major characters, Perrin, is not present in a novel (though Rand was out for most of The Dragon Reborn) — perhaps because some of his events in Shadow Rising occurred during the events of this novel (hard to tell at times) — though he is referenced a couple of times by Mat and Rand. This gives Nynaeve and Elayne more “screen time,” though fans of the series who don’t like Nynaeve will likely find this tedious, especially as most of her storyline in this book feels like a bizarre side-mission (more so than usual with her). Strangely, Nynaeve somehow becomes subordinate to Egwene, who herself becomes a bit of a jerk toward the end, and there is a fair amount of “men are imbeciles” before this book is over (again, more so than usual from the Aiel women).

Pacing is certainly the burgeoning trademark of this series: many would say it doesn’t have any, but they’d be impatient and wrong. As indicated in other book reviews of the series, Robert Jordan patiently spends time with characters, giving us great details on their experiences, far more than most fantasy tales, focusing on that character until, usually, he or she departs the present town for another. This continues for most of this book as well, whether you like it or not: by now, you should be used to it. If you don’t like such focused attention, you probably haven’t gotten this far in the series. This book is about 500 pages of slow-burning set-up, followed by a fairly intense double-climactic pair of showdowns. Some may not like it, but again, that’s what this series is. Oddly, the first of the climactic showdowns happens mostly off-screen, and while that may seem anticlimactic to some, it actually relieves us from a lengthy and tedious battle description, none of which would help advance the characters or stories — perhaps we’ll see it in the movie/series adaptation.

Things get a little saucy in this book, beyond the recent descriptions of female anatomy in the last couple of books, but Jordan is likewise abstemious in his details (while at the same time continuing the fairly ribald attitudes among the Aiel). Some may not like that, but there it is.

While it’s easy to call this another Aiel-heavy book (which it is), we do get the occasional relief by spending time with Suian and her female posse, including Logain, as they have to deal with being stilled, how to survive, what to do next, how to retake the White Tower, and more. This sidestory is both enjoyable (as it brings Gareth Bryne back into our field of vision) and irritating (as the Sisters in Exile treat our heroes poorly, which is always irritating when characters you are rooting for are mistreated especially by “good” people who should know better) … but that irritation gives us a keener look into the world in which these characters live. It matters almost nothing that Suian used to be Amyrlin Seat: she is now stilled — she herself virtually does not matter. She has fallen as far as possible, but she will not let that stop her from protecting The Dragon Reborn … in her own way, of course.

Similarly, there is a bit of a cessation of Moraine’s seemingly-endless secret keeping from Rand, as she finally starts to tell him things, though most of those lessons occur offscreen. At least she is finally explaining things to the Dragon Reborn instead of always trying to run him like a puppet master. By the end of the book we find out why she has changed so drastically, which takes us in a significantly different direction at the end (quite literally for Lan, especially), but at least it is refreshing while it lasts.

The villains don’t get a lot of time here, and in fact the first Trolloc attack doesn’t happen until several hundred pages into the book. This is more of a “there are different kinds of villains” entry in the series, I suppose, as former friends seem to shift their allegiances (or reveal their true colors, shall we say). We get to spend a lot of time with the good guys (except Perrin), and even Mat gets to be heroic again (without ever wanting to). Pretty good book, even if it feels like “nothing happens until the end.” But, whew, when stuff does happen, it’s big stuff.

And we aren’t even halfway through the whole series, yet.

It’s possible the Lord of Chaos wrote this book himself. I’m not saying it’s bad — it was pretty good. A few things we’ve been wanting to happen for a number of books finally happen in this one, if in unexpected (possibly less than satisfactory) ways, such as Elayne, Egwene, and Nynaeve reuniting and becoming Aes Sedai and Rand and Perrin meeting again. We have been waiting for these things for a long time, but we still have to wait for Nynaeve to overcome her block (this is really taking too long), Rand is still having trouble communicating with Mat and Perrin (you’d think they’d be used to being ta’veren by now), plus a few other things here and there. Mostly we are irritated (as we always are in series such as this) by the non-heroes getting in the way of what our core group of heroes are trying to do, especially the Tower Aes Sedai, the Rebel Aes Sedai, the Children (obviously) … basically, we are almost cheering for some of the bad guys to start wiping out some of these second- and third-tier characters (is that wrong of me?).

I said the Lord of Chaos may have written this book because structurally a lot of what we have become used to in the previous installments are out the window here: most chapters have multiple points of view (sometimes switching back-and-forth between characters in a single chapter), the prologue also covers several character groups, the Forsaken get a whole lot of screen time (after being mostly mysterious and obscure characters up until basically the previous book) — including POV chapters!, we leave POV characters before characters leave their locations (though, admittedly, not a whole lot of movement happens in this book, not including Rand’s teleporting between cities frequently), and even the Dark One gets a few lines. He is the one who brings up the Lord of Chaos, so I don’t think he (the Dark One) is the eponymous character — who is it? I don’t know. The characters seem to, so that’s fine.

Some fans seem to dislike this one because not a whole lot happens (which isn’t all that true, but it does sort of feel like it more than the last couple) and it seems more like it stops suddenly rather than wraps up a complete tale-within-the-tale like the last few did so well. It’s almost like it’s a part one with Crown of Swords being part two. I liked it, but I, too, sort of felt like something was a bit missing with this story, but I did enjoy a good deal of the moments in it.

It has a lot more humor than the last couple, perhaps the most since The Dragon Reborn, and a lot of it comes from, as usual, Mat, who is increasingly becoming a great character, despite his flaws (and despite the fact most of the other heroes wholly misunderstand and undervalue him; very frustrating, that). Another of the great humorous scenes involves Loial (finally he returns!) and an unexpected arrival of his fellow Ogiers. Though, the humor of it is somewhat dampened by a seemingly dropped plot point: Rand delivers the Ogiers to where he thinks Loial is, finds out later that isn’t so, and instead of trying to rectify it they seem to be just forgotten … I trust Mr. Jordan enough to believe this is not the end of this storyline.

Even though, as I said, it doesn’t “feel” like a lot of movement or progress happens, enough does to feel like we have turned a serious corner (or are a gnat’s wing away from completing the turn) and a new phase of the Wheel of Time saga is about to happen: finally, Rand is getting the attention (and fear) of Aes Sedai (thanks to the appearance and involvement of Mazrim Taim!), progress is moving on Rand’s three wives situation, dissension may be popping in the Children, Elayne and Avienda have reunited (and revealed some needed facts), Egwene has told the truth to the Wise Ones, and a few other conversations we’ve been wanting to happen have occurred (not all of them, of course). Some good things have happened to our characters, though, as always, they have come at a price. And Rand is sort of coming to terms (not the best way of putting it) with the Dragon Reborn … since it may be more accurate to say the Dragon has been reborn inside him and not just as himself!

And, oh yes, the Forsaken are really starting to make some big power play moves. And the Lord of Chaos is out there doing something (maybe). And the Dark One is intentionally allowing Rand to live and fight. That is perhaps the scariest part of this series. Boy, I am enjoying this a good deal.

If you are looking for a generally good-natured romp through DnD fantasy, you could probably do a lot worse than the mildly-beloved The Crystal Shard. Sure, in the last almost thirty years, this has become noted for being “the first Drizzt story!” even though he is supposedly a supporting character here before his famed skyrocketed him to greatness. I don’t agree with the idea he is a supporting character here, though: he is in it just as much as everyone else, possibly even more than any other individual. He is single-handedly responsible for the most important “big plot” occurrences, which is not to diminish the important deeds his buddies (Bruenor, Wulfgar, and Regis) do throughout the adventure. He is very much a main character in a novel about these four ragtag outsider buddies.

This is the kind of DnD fantasy I would write, or at least the kinds of characters I usually create: outsiders, yes, but all are generally kindhearted and atypical members of their races/classes; only Regis is really flawed (I don’t use Halfling thieves anyway), and Drizzt, Bruenor, and Wulfgar all show their strong-yet-sensitive sides frequently in their adventures. Because of this absence of nonsensical character conflict (there is some, with some supporting characters, but that’s expected), the book is all the more enjoyable: the good guys are good, the bad guys are bad, people learn their lessons (except Regis), and it’s all very clean, very straightforward, very enjoyable (for what it is, a goofy DnD fantasy romp).

The second of this trilogy is rather darker than the first: not only are our heroes in much more peril, the peril is far more personal than the hordes of the first book. Poor Cattie-Brie is terrorized for much of the book in very dark and intimate ways, making her sections of the book more disturbing than the general slaughter throughout. Our main quartet of heroes likewise go through personal losses throughout, resulting in a very different ending from the first installment.

Even with the darkness (perhaps because of it), this book feels more like Dungeons and Dragons, likely because the scale is much smaller than the grand battling armies and squabbling nations of the first book. This is a small group of adventurers fighting some battles (not too many), sneaking around gathering supplies and information, facing mysterious forces everywhere they go, and then suddenly a huge dragon shows up and things fall apart quickly.

Bruenor is a bit of a jerk for most of the book, learning too late his friends and comrades today are more important than trying to revive the past, but at least others can benefit from what the friends have learned and suffered throughout this installment.

Our heroes are at a very low point at the conclusion of this book, but despite their warranted glumness, we have the sneaking suspicion things will get all straightened out by the end of the final part.

We seem to find ourselves on a bit of a formulaic track by this time. Once again Dorothy and some new people (who don’t really matter) find themselves on a magical trip to who-knows-where that eventually becomes the road to Oz (as the title makes a bit clearer this time). At least there is a bit of a better payoff this time: instead of just getting to Oz then leaving right away (as in the previous book), this time Dorothy and friends get to celebrate Ozma’s birthday (how they know it’s her birthday considering her/his life story is anyone’s guess — perhaps they just declared it is her birthday, which is fine). Toto is back this time, and so are some of the other ol’ friends we haven’t seen for a bit (most notably Jack Pumpinkhead), and most of the A-list friends are back, though just briefly at the end (though “the end” is a rather drawn-out affair). Along the way we meet new sorts of wild and wacky characters, most of them annoying, but all the trials and obstacles are overcome with a snap, a shake, and a sure-why-not and all is well. If you are interested in seeing the ol’ gang again, this is nice, but it’s again mostly a showoff of Baum’s diverse character creative abilities (including some stars of other novels of his, such as Queen Zixi). Not the worst, I suppose, but you are likely going to find the first half far more tedious than the second half.

Oh, hello again. So nice to see you. Here we are, back as a class for the first time in donkey’s ears. I dunno, it’s a saying, I heard. Anywho, it’s great to be back for another season of Redeeming Pandora. We’ve got some fresh voices, some familiar faces, and another season of tricks and treats just waiting to be explored. As is sometimes our wont, we close our season opener with a brief history of some of the books I’ve read over the summer (including some late spring entries, just for giggles). This smattering of reviews is a bit shorter than usual for two main reasons: I read mostly very long books, and I spent a preponderance of the summer playing Final Fantasy XII (while drinking too much Oberweis sweet tea and eating too many miniature pretzels), to be explored next time. For now, sit back and perhaps get motivated to read a few of the works reviewed for your enjoyment.

The Inimitable Jeeves (Jeeves & Wooster #2), P.G. Wodehouse ⭐⭐⭐⭐

In a strange way, picking up a novel-length Jeeves and Wooster story is a bit intimidating: the humor seems best in compact, focused installments such as short stories — why try to expand it to a whole novel? However, Mr. Wodehouse encourages us immediately: this novel, while loosely connected, is mostly a series of vignettes, as efficiently compact and contained as one can hope. What periodic imbrication occurs brings more humor, not prolonged suspense or boredom. Fans of the Fry and Laurie adaptation will recognize a good number of the episodes from this book, as many of the early episodes of the series are taken from the chapters within. It’s difficult to go wrong with a Wodehouse book about Jeeves and Wooster: read this one and find out why.

Airborne Carpet: Operation Market Garden, (Battle Book #9) Anthony Farrar-Hockley ⭐⭐⭐

Another engaging Ballantine Illustrated volume, this brief overview of Operation Market Garden provides a limited eagle-eye view of both sides of the conflict (though mostly the Allies). Having somewhat recently read It Never Snows, wholly from the German perspective of the battle, this Allied-heavy perspective is a helpful counterpart. Farrar-Hockley has certainly read a diverse number of primary sources, quoting frequently from first-hand accounts and diaries of those whose experiences don’t regularly get presented in the grand versions of this engagement. The Polish soldiers and many of the British troops with significant roles are mentioned here, even those who do not get mentioned in other accounts, so Farrar-Hockley’s coverage is widespread (if also somewhat terse, considering the limitations of the picture-dominant format). It’s a good survey of this battle, especially of the Allied leader conflicts in planning and executing the massive endeavor. Ballantine’s Illustrated History of the Violent Century was a great series of series that should not be out of print. Bring it back! (Or, buy every copy you find wherever you go and give them to me.)

On Conan Doyle, Michael Dirda ⭐⭐⭐

Though the title page tells us the subtitle is “The Whole Art of Storytelling,” the real subtitle of this should probably have been “But Mostly On Dirda’s Experience with Doyle’s Works,” instead of its purported subtitle, which is only addressed briefly toward the end. This is not a criticism, mind, simply information for you, the unsuspecting future reader: a good deal of this is a personal reflection of Dirda’s reading youth, his early experiences with Doyle and other mystery/sci-fi/fantasy/pulp adventures in those halcyon days of dime-store magazines and the freedom of youth to travel their hometowns without worry or danger, as well as his later-life experiences with the Baker Street Irregulars, and how he has lead the best life possible (as usually comes across in his collections of book reviews) without sounding too snobby about it.

As usual, Mr. Dirda suffuses his commentary with lists of authors and works you’ll want to track down, which is not always as facile as one might suspect in the Digital Age. You’ll likely want a pen and paper (or word processor) close by to enumerate the suggested readings throughout in addition to the recommended works at the end of his reflections.

The only other flaw (if you might consider Dirda’s personal histories an intrusive flaw) is Dirda’s awkward inability to balance his general enthusiasm for Sir Conan Doyle with his (ACD’s) flaws as Dirda sees them, especially Doyle’s Spiritualism. Toward the end, Dirda attempts to say he respects Doyle’s religious/spiritual beliefs and his willingness to write and act on them so much, but since he (Dirda) clearly disagrees with it, his respect is tepid and nominal at best. He is clearly embarrassed by Doyle’s belief in fairies and even goes so far as to encourage us not to read some of Doyle’s work in certain areas.

The rest, however, comes off as an energetic, enthusiastic appeal to us to delight in more of Conan Doyle’s oeuvre than just Sherlock Holmes (though he clearly wants us to read those works again and again as well). He does mention Jeremy Brett briefly, with mild approbation, perhaps not as much or effusively as some of us may prefer, especially as it is only in passing with Robert Downey, Jr. and that newer BBC modern version. He discusses Basil Rathbone’s movies, too, but his delight is hampered by Nigel Bruce’s Watson (or, at least, the writers’ treatment of the character). On the whole, Dirda is dissatisfied with the history of Sherlock Holmes on radio and screen, which is why he continues to enjoin us to use our imagination with the real stories themselves (along with a few other adaptations he recommends), and especially increase our awareness of the wide range of Conan Doyle works as well: the autobiographies (not the fairy ones), the Challenger stories, Gerard, the historical adventures, the White Company, the horror short stories, and more. But not the fairy works.

Rough patches and all, this is a fast-paced read that does its job well: it motivates us to go read a lot of diverse Sir Arthur Conan Doyle works.

Welcome to part 1 of a non-committally “multi-part” series exploring a few television-related topics. As we all know, in today’s break-neck-speed world of ratings, advertisements, and politically-correct-only viewpoints, sometimes shows get axed before they get a chance to shine. Sometimes, this is a good thing. I don’t watch a lot of contemporary programming, but I’ve seen a few halftime advertisements for programs that have made me (and surely us all) reflect “that won’t last,” and rightfully it doesn’t. The other times, though, the decisions of powerful, nameless, soulless executives are just plain wrong: shows with great premises and engaging potential are ripped from our bosoms too soon and dashed upon the rocks of Impatience and Pecuniary Gluttony before our tear-sodden eyes. I would like to reflect now upon a few of these shows that left us far too prematurely, either during their first season or only after one season (in mostly no particular order).

I know, I know. “Only honorable mention?!” you say. “That’s the worst and/or best example of this problem!” you say. Such have the people been saying for 15 years, including the other 75% of my birth family. To be honest with you, loyal readers, I never watched Firefly until a few months ago, fifteen years “late.” My family had even purchased the digital video discs of the series when it came out, which I have been carrying around for over a decade across three changes of address. Finally, though, I popped them in and watched the series. You know, it’s not too shabby after all. It is a very rich universe with a great deal of potential, interesting conflicts and backstory, and a ragtag crew of disparate desperados, all led by the least-likable character on the show, Malcolm Reynolds, played by the least likable actor on the show, Nathan Fillion. That his character is openly antagonistic toward religion is only icing on the cake. I could never watch Castle, either. I’m just not a Fillion-atic. It breaks my heart he is portraying one of my favorite Marvel characters, Simon Williams (a.k.a. Wonder Man) in the upcoming Guardian of the Galaxy sequel (though, since they aren’t the real Guardians of the Galaxy, and the Ultimates Universe is mostly shash, it doesn’t matter). Anyway, the series and the universe, despite Malcolm Reynolds, are intriguing. The “everyone speaks Chinese” thing seemed farfetched for the not-too-distant future, but I suppose if some catastrophic event results in the West and China uniting, I could see it happening, sure. The thing that bothered me the most about the show is the best character, Kaylee, is treated horribly by practically everyone, including the writers/producers. No one appreciated or talked to her appropriately, and the backstory and occasional dialogue by and from her from the lesser-skilled writers was really a low point. On the other hand, as I said, the interesting universe and its many layers of conflicts, especially the absence of aliens, the sci-fi/Western milieu, the odd mix of moral codes in the crew and universe as a whole, plus the “who are they really?” about most of the crew all indeed make for a good time and an experience that should have lasted much longer than it did. I agree. It’s not the bee’s knees, but it is a good idea. It certainly could be easily expanded by books and cartoons and comics and a whole slew of things, but if mastermind Joss Whedon wants to keep it all locked up in his secret vault where only he can take it out and pet it and hug and kiss it, so be it.

This may be the least-painful entry on the list, not because it is first but because the safety net is indeed the largest: even though the fantastic 1975-1976 television show Ellery Queen lasted for only one season, the only entry on this list I wasn’t alive to see the first time around, the entire Ellery Queen Universe consists of, what, a couple of radio series, a couple of television series, some films, comics, a magazine that’s been going on since World War 2, and a whole lot of novels and short stories. This may be of small comfort (as it is with the heart-breakingly-too-soon-cancelled Nero Wolfe series), if your main attraction to the Ellery Queen series is the performance of Timothy Hutton’s dad Jim Hutton and David Wayne as Ellery Queen’s father Richard Queen. Much like the interplay of Timothy Hutton and Maury Chaykin in Nero Wolfe, the highlight of the show is the two leads acting with each other. The mysteries are usually interesting, sure, and the semi-regular guest appearance of John Hillerman as Simon Brimmer (created just for this incarnation of Ellery Queen) is marvelous (especially as it adds to this series’ more comical-but-not-slapstick interpretation of Ellery Queen), and the “hey, it’s that one used-to-be-famous guy and gal!” seven times over per episode guest cast (like Murder, She Wrote used a decade later) is delightful for fans of television-radio-movie history. But the real treat, as I said, was the chemistry between Jim Hutton and David Wayne, and we, frankly, deserved several more seasons of it than just one. The stories already existed. The Used-To-Be Actors and Actresses were aplenty. It could have lasted.

Surely, several one-season-only fine cartoon shows could qualify for consideration here, especially if made by Hanna-Barbera: Herculoids, Hong Kong Phooey, Hair Bear Bunch (and others that doesn’t start with “h”). Pirates of Dark Water, for example, was the impetus for this article, but since it technically is more than one season, it ironically does not qualify (and deserves its own article for its sheer greatness anyway — stay tuned). 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo only qualifies for this list because, while it may have been complete as a one-season show, it did not get its chance to finish the story, which is horrible. As you know, I’m not a huge fan of scary things, but this show, a few notches above the usual dark mystery of Scooby-Doo shows that almost always say “supernatural dangers have naturalistic explanations,” is distinctly in the vein of “supernatural dangers are supernatural indeed” and works very well, even though it should be a prime example of everything we harangued against a few issues ago (sixteen ago, to be precise). With Vincent Price along, Scooby and Shaggy and Velma and some kid named Flim Flam put right what once went wrong (you can probably guess who’s to blame) in the harried nether realms of the Himalayas. All we needed was a few more episodes and it would have been all finished — why cancel a show three or four (or possibly even only 2 very full) episodes before it could finish telling its story?

This rather bizarre gimmick of a show mixed iceberg-like mystery (there’s much more under the surface) with play-at-home game show. This one’s definitely not for kids: it’s possible the inhabitants of Twin Peaks, Washington would feel uneased in this goofy ol’ town. A mysterious fax (I think that’s Old Tongue for “printed out e-mail”?) shows up in mild-mannered IRS Agent Jim Prufrock’s office and right away you’re thinking “hey, that’s a name from that poem” and suddenly things get weird. But not only is it a show about a mystery and bizarre things going on in Push, Nevada (things of Modernist Poetry and Classical Greek Drama subject matter, which can never be good for anyone involved), it is also a play-along-at-home follow-the-clues adventure. This gimmick (and I don’t use that pejoratively here) was pretty clever — not original, not unique, but clever. The show had a self-determined end point: it had a whole mystery to uncover and reveal, an end and purpose, but that was apparently not good enough for the impetuous Decision Makers and Plug Pullers of 2002. Oh, sure, they revealed the rest of the clues for the play-at-home game show, and some eagle-eyed viewer won a thousand bajillion dollars, but for me that was not the point of the show. I wanted to know where the show was going, and I didn’t care too much about the prize money. Apparently, I was alone. Not even co-creator Ben Affleck seems to have anything to say about the show part, such as where the mystery was going. Pity, that. I still want to know what was supposed to happen.

I admit this is the one show on the list for which I was alive but not old enough to watch when it first came out, which is partly why the list is limited in its way, but having seen the episodes multiple times, I still cannot fathom why this series is only six episodes long. Sure, it has running gags, but those running gags do not prevent anyone from understanding 99.9% of that particular episode. Surely its appeal to me is its alignment with the kind of verbal, intelligent humor I prefer, but its admixture of nonsensical visual gags is somehow over-the-top without being too much or too obvious. It is a sort of intelligent slapstick that does not resort to the painful Three’s Company-type “humor” (no offense to Three’s Company fans). It must be the only series to be longer (total minutes-wise) in its motion picture incarnation than in its episodic television incarnation. As Barney Miller proved, a humorous cop show has great potential and longevity — and Barney Miller almost never left the squad room in eight seasons! This series had so many positive things going for it. It was just too smart for its time, apparently. For those who have trouble associating “smart” with Naked Gun, go back to the original Police Squad! and see what comedy gold was there from the beginning.

Another but six-episode series, this science-fiction romp likewise had great potential. It has not aged nearly as well as Police Squad!, that is true, even though it is a decade younger, and it has clearly been surpassed by others of its ilk (obviously Deep Space Nine and Babylon 5), but Space Rangers had a certain I-don’t-know-what. Perhaps it tried too hard: the production demands with a technology that wasn’t quite there yet, the terminology of the universe, the outfits … but still. Its main cast is a veritable “hey, it’s that one guy/gal!” collection. It’s about the space station and dangers of the frontier and enemies close to home, but it’s also a world that isn’t nearly so refined as either the Star Trek or even Babylon 5 universes, and that ruggedness had a wide-open field for storytelling and character development. This show should either never have been made or allowed to go for many seasons.

The 1992-’93 television season was an interesting time. Some excellent shows began then: Batman: The Animated Series, X-Men, Highlander: The Series, Goof Troop, among others. Some not great shows began then (let’s not mention any). And there was #8 on our list as well as #7, Covington Cross. Speaking of “hey, it’s that one guy/gal!” shows, this is Britain’s version, with famous British people, starring the great Nigel Terry. With the freedom of Generic Medieval Setting, Covington Cross had no historical boundaries or chronological limitations requiring it do this or not do that other than Be Medieval. With Nigel Terry. Unlike all the Serious Time Dramas with Some Comedy, Covington Cross did not have a set story it had to tell: it could just be something fun and different and clever, and boy was it clever. Go read the plot description of the pilot episode and most of you will think “oh, that’s like that other popular medieval drama that’s all the rage these days,” but then you’ll see the date and realize, “oh, that’s four years before the first book came out!” Like Police Squad!, Covington Cross was just ahead of its time — too good, too clever, too expensive. Ironically, the thing that seemed to irk Thomas Paine so much, about England ruining America (or whatever he called it) because England was running America from afar seems to be the inverse of this show: America ruining England’s Covington Cross because American ran England’s Covington Cross from afar. This was a good show, and if I could understand that before my teens, surely other people could have understood that as well. Did I mention it had Nigel Terry?

Similar to and unlike what we just said, Dark Skies took on the challenge of telling the story of modern America from a different perspective: the right one, in which so many of the major events of modern America happened because of … aliens. I’m not a huge fan of alternative history, but Dark Skies was a good mix of history and revision and scary alien menace. Perhaps you think I’m describing some X-Files knock-off. No, you’re thinking of X-Files seasons 9 and 10. But seriously folks, Dark Skies should not be remembered as an X-Files knock-off. It had some similar ideas, sure, but unlike X-Files, which was all some secret malarkey that changed every couple of seasons and our heroes were never to know about it, in Dark Skies our heroes get on the inside track from the very first episode and spend the whole time trying to learn more about it and get better prepared to actually fight it. It’s like a sensible fan’s response to what we wanted to see in X-Files: the good guys actually being allowed to fight the future. If this got cancelled because it was “too much like X-Files,” whoever made that decision clearly did not understand either X-Files or Dark Skies. Recently, I saw a soupçon of the five-year plan for this show: twenty years after the show came and went too soon, I was re-angered by the idiocy of the Decision Makers who cancelled this show, knowing as they did what was in store for this show and what incredibly intelligent places it was going (significantly different from how it began in season one). It was going to grow and change and re-invent itself and do all the things J.J. Abrams’s shows get credit for inventing a half a decade before Felicity. Dark Skies took one of the clever-but-not-even-original ideas X-Files presented in a horribly frustrating way and did it in a more engaging and rewarding way, took what Falling Skies was going to do 15 years later and did it 15 years before, and a whole lot more. It was going to be five seasons; it knew where it was going; it knew the story it had to tell. What went wrong? Where was the faith? Where was the love?

Speaking of 5-year plans, we should know by now if a show has a solid five-year plan and is allowed to work it to its fruition, we end up with something magical and exquisite. Clearly, as always, I’m speaking of Babylon 5. Farscape may or may not have had a five-year plan, but it needed its fifth season to finish telling its story fully, but, sadly, it didn’t get it. NewsRadio as well. Battlestar Galactica may or may not have had a plan, but it got to finish telling the story it wanted to tell, and those of us who are intelligent appreciated and enjoyed the conclusion to the story. And then: sequel. And/or: prequel.

I haven’t seen Caprica. I probably won’t. Ah, but Crusade! Why was this cancelled? If you are a sequel to the greatest show of all time, which, as we all know, Babylon 5 is, why would Decision Makers not give the Creative Team the benefit of the should-not-even-have-existed doubts and say “you just made us forever rich and famous and happy by giving us the best show ever, and since you want to continue the story/universe in a new and fresh way and actually know what you want to do and where you want to go, full speed ahead!” and instead say “you just et cetera et cetera et cetera too slow, I change my mind, it’s over before we can get to know everyone”? Why would you (the third of the three different unnamed antecedents of “you” in the previous sentence) do such a ludicrous thing? Have you (I’m talking to you, now, faithful reader) seen the cast list for this show? This show discovered everyone! (You’re probably thinking that argument will be used again soon in this list.) I don’t understand. No, Crusade is not Farscape — but even the first couple of post-pilot episodes of Farscape are “not Farscape” just yet anyway. Even that show had to find its identity. And after Babylon 5, come on. Crusade knew where it was going, and the Creative Team already proved it knew what it was doing. This is possibly the most irksome entry on the list for me, since I know deeply it could have become something great given the opportunity, even with the monumental task of being a sequel of sorts to the greatest show of all time.

This is the most recently enjoyed series by me on the list, one my parents introduced to my wife and me earlier this year. Coming to us from Australia, reminding you we at Redeeming Pandora are truly international, Mr. and Mrs. Murder was and is and always will be a very clever character-driven mystery show about a loving husband and wife couple (rather rare on television these days) who clean up crime scenes for a living. Not like the CSI clean up teams, mind you, the actual cleaning up cleaning up people: the ones with mops, vacuums, wet wipes, and lots and lots of gloves. Like most good mystery shows, the characters are very smart (another rare thing on television these days), well-read, well-rounded, somewhat flawed, quirky, very much in love, and very fun to watch. Because the show comes to us from Australia, none of the American Television Company mantras and flaws are there (whether traditional or contemporary), and so even though it seems from afar to be overly-familiar-television-mystery fare, it uses those traditional mystery show tropes in fresh and clever ways. It’s quite good. Making the pain of its premature non-renewal even more painful, aside from how clever and enjoyable the show was right from its first episode, by the end of the season it had potentially given us a nemesis for our hero, Charlie (the “Mr.” of the title — the loving couple of cleaners-turned-amateur-sleuths). And while shows like Bones and NCIS have proven the “nemesis of the season” idea can get tedious rather quickly, at least they had the opportunity to work it through. This is a quintessential example of the “not enough viewers gets even very clever shows cancelled” heartbreaking disease so prominent today. This show could have and should have gone on for quite some time. Come on, Australia — what happened here?

For some inexplicable reason, Television Executives, those unimaginative soulless fiends to which we’ve been referring throughout this journey, continue to “green light” (as they say in the “biz”) science-fiction programs, even though these same Decision Makers apparently hate them passionately. Travel back with me to the Golden Age of TV Sci-Fi, the late ’80s to the early ’00s, a time that gave us really great shows like TNG, DS9, Babylon 5, Farscape, Lexx, Quantum Leap, Stargate SG-1, and others. We also had this overlooked gem. Before Voyager, Lost, Terra Nova, and all the other more recent series that copied some of this potential great show (that, admittedly, borrowed from Battlestar Galactica, which is just the Aeneid in space anyway), Earth 2 gave us a diverse, intelligent show that fell prey to the Low Ratings Disease. Shame on you, audiences: we had something potentially great in our hands and you (not me, since I watched it all) let it slip away. This show had a little bit of just about everything you need for a good science fiction show: a ragtag crew far from home, religious conflicts, misunderstood aliens, cyborgs, disasters, internal strife, children as the last hope for humanity, and so much more. Sure, when I put it like that it may sound like a hodgepodge of every science fiction show, but somehow it came across (to me, and not just because I was young) as something different, something that could have lasted much longer than one season. There was great potential for so much, not just on the new planet but also back home — this could have given us many seasons of intrigue, mystery, action, adventure, romance, science, ecology, anti-colonialism, and so much more. I guarantee if this show got rebooted intelligently today (by which I mean not in a heavy-handed “social issues are more important than people of faith” sort of way), it could work very well and perhaps tell its whole story, which surely would be an enjoyable story indeed.

Clearly we live in a day in Television Land in which “fresh, clever, morally upright ideas” are anathema, and “shoddily-rehashed superhero ideas” and “viscerally-appealing basest aspects of humanity are ‘good’” shows are praised and “green-lighted.” Again. And again. And again. It’s an odd mix, perhaps trying to tell us “normal people are bad but hey, that’s okay,” so “only supernatural beings are good, and since the supernatural is a hollow lie, no good exists for real.” Inexplicably to intelligent people, the other people in this world tell us shows like Breaking Bad, Damages, Guilt, Scandal, Revenge, Dirt, Dexter, The Sopranos, Desperate Housewives, and a whole slew of other shows focusing on protagonists doing horribly evil things are “great” and “groundbreaking” and other sorts of positive superlatives, and these same people then ask in all sincerity, “why are human beings so bad and hateful and angry and selfish all the time?” These are the same people, mind you, who tell us “people are cosmic accidents from dust and monkeys with no purpose or hope” and then, still in all sincerity wonder “why do people kill and hate and lie and steal and destroy?” Then they usually mention the calendar year, as if that has some bearing on the argument.

Enter (six years ago at the time of this writing), a very fresh and entertaining (if somewhat saucy at times) relief from such a world: a show in which the heroes care about doing good, making the world a better place, and keeping us safe from people who want us to be unsafe. The show was a frenetic mix of a lot of different things: you’ve got the beloved ’80s mismatched cop duo idea (one cop is stuck in the ’70s days of shoot first, massage the evidence, drive fast, smoke and drink and be foxy, and, if time, ask questions if it’s not too late but since your intuition is usually right you don’t need to ask questions anyway sort of cop, combined with the young, up-and-coming technology savvy, politically astute, by-the-book cop), an ethnic lady of ethnicity in charge of the police force that should have appeased the group that needs appeasing by that sort of thing, heroes with lots of flaws and moral ambiguity, a quirky cast of characters beyond the quirky heroes, and the villains! My heavens, the villains are possibly the second most enjoyable part of the show, in that week after week the villains are, well, sort of the opposite of stereotypical villains: they are intelligent, funny, and come very close to being the stars of the episode (sort of reminiscent of Barney Miller), yet we don’t end up rooting for them in any way (except for villain-turned-ally Julius). Bradley Whitford as Dan Stark, the out-of-time cop who, like me, distrusts technology and proper procedure (after all, didn’t we learn from thousands of episodes of Law and Order and CSI and Psych warrants usually are just for sissies after all?) is so unlike every other role we’ve ever seen him in, the sheer zest and enjoyment of watching him be funny and free and wild and reckless should have been enough of a reason to keep this show around for several seasons. Plus it’s got wit (akin to Police Squad!, in a way), Colin Hanks, romance, special effects, and I honestly don’t know why this show stopped … oh, wait, yes I do. It was good.

Here we are, full circle. You know who made Lost the good show it was? Nope, not J.J. Abrams — Carlton Cuse, that’s who. Where did he get his training? Brisco County, Jr., that’s where. I think it was Benjamin Franklin who said, and I quote, “The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. may not be a perfect show, but it’s as close to a perfect show as imperfect people can make,” unquote. Before Firefly came along with its Western Sci-Fi Comedy Adventure (that at times takes itself a bit too seriously), there was the great Brisco County, Jr.: a Western Sci-Fi Comedy Adventure that never took itself too seriously. Before Nathan Fillion came along being pseudo-manly and pseudo-complicated heroic, there was … Bruce Campbell. Manly. Heroic. And manly. I don’t want to get all libelous and whatnot, but Bruce Campbell, for me, is the antithesis of Nathan Fillion, mainly in the “I want to watch a show with him as the star” category.

Let’s talk briefly about how many fantastic things this show had going for it: I believe we have already mentioned Bruce Campbell as the eponymous Brisco County, Jr., Harvard educated son of the West’s most famous and successful lawman (Brisco County, Sr.) bounty hunter (who, MacGyver-like, almost never uses violence) extraordinaire. Do you want more? We have already mentioned Western Sci-Fi Comedy Adventure. How about the late great Julius Carry as Brisco’s rival-bounty-hunter-turned-best-friend Lord Bowler? Christian Clemenson as Socrates Poole, lawyer and confidante. Kelly Rutherford as Dixie Cousins, gangster moll/sort of love interest for Brisco. Comet the Wonder Horse as himself. Every episode lovingly recalls us to those halcyon days of serials, much like the Indiana Jones movies, in which plots moved quickly from crisis to crisis, but BCJ allowed for plenty of character, humor, intrigue, romance, heart, intelligence, and more good things. Let’s not forget John Astin as Professor Wickwire, the knowingly anachronistic scientist always encouraging Brisco (and us, the science-loving audience) to be on the lookout for The Next Big Thing. (Before you think it’s just some Wild Wild West rip-off, trust me when I say “it isn’t.”) And the villains! Billy Drago as main antagonist John Bly (no one does villain like Billy Drago). M.C. Gainey as Big Smith (a diabolical Little John). Oh, and you know that rousing theme you hear all the time during the Olympics, not the fanfare but the other rousing get-up-and-go-with-gusto music? Yeah, that’s actually the theme music to Brisco County, Jr.

Having established this show has practically everything you need for success (i.e., Bruce Campbell with bonus elements), let’s talk a little about its premise, especially if you think John Astin’s inventor-scientist character is the sum total of the Sci-Fi in Western Sci-Fi. U.S. Marshall Brisco County, Sr. has just successfully rounded up all 12 of the notorious John Bly gang, but for some reason the Robber Barons and Government Decision Makers have put them all on the same train together, and somehow the bad guys escape, kill Brisco County, Sr., and flee in all directions. The Robber Barons hire his bounty hunter son Brisco County, Jr. (and a few others, such as Lord Bowler), to track them down and restore order to the West. And that’s just the opening credits of the pilot. Then comes … The Orb. I don’t want to spoil it for you, but The Orb is one of the most intelligent pieces of television history I’ve ever seen. Brisco County, Jr. showed me television series can be intelligent — I had already known that from Star Trek and Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood and a few other things, of course, but BCJ showed me television shows, if handled by intelligent people such as Carlton Cuse, can plan ahead, come up with engaging story arcs and intentional character development, and quality episodes that not only entertain but also demand an intellectual response as well. Brisco County, Jr. did not just come up with neat ideas and change directions to make the story bigger and better, oh no: BCJ worked out ideas and directions in advance and started heading on that cohesive path from the beginning — just like all writers are supposed to do anyway. As you know by now, that’s one of the key factors in why Babylon 5 is the best show of all time (and my favorite), and it’s one of the key factors in why The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. is the most heartbreakingly early-cancelled show of all time. It could have gone in several engaging directions, and from what I’ve learned about the plans Mr. Cuse and Co. had for where the show could have gone, beyond just “nabbing the Bly Gang” and understanding The Orb, it had as much possibility as The Ol’ West itself — and that’s a vista of great and wondrous and plentiful possibilities indeed. So I’m going to file my claim for The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. as the most regrettably-prematurely cancelled show of all time (real fans saw what I did there).

In one sense, this has become a self-perpetuating problem. As mentioned throughout, we, the mindful viewers, having caught on to the wiles and dastardly habits of this abominable practice are reticent to even watch new programs until after a season or two is safely on some streaming service so we don’t get our hopes and hearts attached to some new cast of characters only to have them teleported into the Nether Realms of Cancellation all too soon. And because of this reticence, shows get low viewership, unsatisfactory ratings, and cancelled. It’s a terrible cycle.

Another facet of the problem is the mind-blowingly nonsensical decision by the Creative Teams and their Advertising Buddies not to let us know “hey, there’s actually a cohesive story here you’ll want to dig into from the beginning.” That’s one of the reasons I didn’t start watching Lost until a few seasons into it: the show looked interesting, but all the initial commercials made it seem like Gilligan’s Island: The Drama. Now, had I known there was going to be a very interesting story arc to the whole thing, I may have started watching it from the beginning. Thankfully, this is one of the few shows that had a faithful following enough to allow it to tell its complete story (and yes, most of you are still wrong about its ending and the point of the whole show). But some shows are not so fortunate: take Pan Am, for example. All the advertisement for it was just “here’s a period piece drama about aeroplanes!” Now, if they had said, even briefly and quietly, “but wait, there’s more: there’s an ongoing story of espionage and conflict,” I might have given it a look — and so, likely, would have thousands of others. I’m not saying you have to spoil all the surprises, but don’t expect me to watch a show just hoping to be pleasantly surprised there’s more to it than what all the millions of advertising budget monies have made it out to be. I did that with Brisco County, Jr., and Fox Executives broke my heart.

“But wait!” you shout. “What about Freaks and Geeks and The Prisoner and My So-Called Life, and all the other great cancelled-too-soon shows you haven’t seen yet?” Whoops. Let the cat out of the bag at the end there. No, I have never seen Freaks and Geeks, and since I’m not in any way impressed with the output of these stars today, the thought of watching a show with them before they were stars does not grip me. I remain ungripped (also because I staunchly refute the eponymous appellations, a subject for another time). I do want to see The Prisoner, definitely, and I surely should, but since they sort of knew it was going to be cancelled, it had the chance to wrap up its story albeit hastily, I’m told (this is somewhat similar to BCJ, at least, in that it does come to a nice conclusion, but it could have gone on for so much longer). And godspeed trying to get me to watch My So-Called Life.

Maybe this was just a subconscious yearning to return to the halcyon days of the early ’90s, when life seemed simple, and quality science-fiction shows were coming at us left and right, video games were done in glorious 8- and 16-bit majick, Comic World was on 16th and Central, Mystery Science Theater 3000 was still being made, the sky was blue, birds were singing, and people seemed to laugh more, then. Well, maybe. But that’s a topic for another time. Let’s not wallow in regrets or the past. Life is mighty good today, in its own way.

Today we live in a fantastic-in-its-own-right age of excellent board games and Vanilla Coke and honey wheat braided pretzels and hula hoops and fax machines, an age in which we can revisit these prematurely ended shows of yesteryear and so many more, thanks to the advent of digital video discs, streaming services, and The Next Big Thing. The joys and potential joys of these series live on in our hearts and minds and collections and clouds.

So there’s that. And that’s my list. What’s yours?

The 1970s were a completely unique and overwhelming decade, full of eccentric people, exciting inventions, and standard-changing events. Familiar names such as Richard Nixon and Michael Jackson came into light, as well as many other iconic people and things. The 1970s were an interesting and important decade.

Possibly the biggest achievement and event of the early 1970s was the Title IX. According to TitleIX.info, which is the officially Web site for this Act, “Title IX is a law passed in 1972 that requires gender equality for boys and girls in every educational program that receives federal funding.” A vast number of people have no idea Title IX even exists or that it applies to things other than sports. In reality, Title IX addresses 10 different subjects: Access to Higher Education, Career Education, Education for Pregnant and Parenting Students, Student Employment, Learning Environment, Math and Science, Sexual Harassment, Athletics, and Standardized Testing and Technology. Before Title IX, girls were unable to participate in the majority of team sports, having only cheerleading and dance as options. Title IX requires if there is no team for girls, girls must be given a fair chance to try out for the boys team while receiving no prejudice based upon their gender. Title IX also opened up doors for any woman who wished to become involved in the fields of math, science, or law. Before Title IX, girls could be denied admission to a college simply because they were girls. Oftentimes, even when a female application had better grades and credentials she was denied admission so the opening she deserved could be given to a male student instead. Title IX changed this drastically. Before Title IX was passed, there was great discrimination against girls, but even more so against girls who were pregnant. Schools were able to expell students who became pregnant, especially if they refused to abort the baby, even if it was due to rape. Title IX ensures if schools have special programs for pregnant students, they are not mandatory and their content is just as good as that which non-pregnant students receive. As seen in these points as discussed by TitleIX.info, Title IX completely changed things for girls everywhere, giving them their first fair chance at many things that had been seen as only for boys for many years.

Richard Nixon, who was elected as the 37th President of the United States (1969-1974), was born in Yorba Linda, California on January 9, 1913 to a grocer and his wife, named Francis and Hannah Nixon. Seeing how discontent his parents were with their circumstances, Nixon became increasingly ambitious and inspired. Nixon graduated from Whittier College in 1934 after having been elected as president of the student body and discovering he had apt skills in the field of debate. He married Thelma Catherine “Pat” Ryan, whom he knew from his local theatre group, in 1940, and together they had two daughters named Patricia and Julie. Richard served in the United States Navy during World War II from 1939-1945. After this, Nixon began pursuing his political career. The man represented his district of California in the House of Representatives. In 1950, Richard gained a position in the U.S. Senate. Nixon served as vice president to General Dwight Eisenhower for two consecutive terms, starting in 1952. Nixon ran for president in 1960, but was beaten by John F. Kennedy in what was one of the closest presidential elections in American history. Many assumed his political career was over when he then lost an election for Governor in California merely two years after he lost to Kennedy. However, Richard Nixon ran again for president in 1968. He won the election and began his term. The Vietnam War had caused much controversy among American citizens, so Nixon developed a strategy to achieve what he referred to as “peace with honor,” commonly known as Vietnamization. This trained the army of South Vietnam how to fight for themselves while slowly withdrawing American troops from Vietnam. A peace agreement with the communist area of North Vietnam was reached in January of 1973 by Nixon and his administration officials.

In 1972, when Nixon was running for reelection, the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate Hotel in Washington D.C. was broken into and burgled by operatives associated with his campaign. Nixon firmly denied any knowledge or involvement in this theft, but many members of his administration had knowledge of it, and later secret White House videos confirmed he was indeed involved and had only attempted to cover that fact up. Nixon, rather than being impeached by Congress, resigned from office on August 9, 1974, making him the only United States President to resign from office. On April 22, 1994, Nixon had a stroke and died in New York City.

The 1970s can claim many interesting inventions as well. The Post-It Note was invented in the 1970s by Art Fry and Dr. Spencer Silver. Art Fry, a member of his church’s choir, grew increasingly frustrated as week after week his bookmarks fell out of his hymnal. The man began searching for a bookmark that wouldn’t fall out but also wouldn’t damage his book. That was when he observed his colleague, Dr. Spencer Silver, had developed a strong adhesive that left no residue and could be continuously repositioned. Art applied this to the edge of a piece of paper, creating the first Post-It Note. Arthur and Spencer watched as their colleagues quickly gained interest in their invention. Here was a new and unique way of both communicating and organizing. When shown to test-markets in 1977, no interest in the product was shown, and for the time being, Post-It Notes had failed. However, the product production exploded in 1979 when a massive consumer sampling strategy took place. Post-It Notes continued to gain popularity as time progresses.

Another interesting invention of the 1970s is the floppy disk. The floppy disk was created by Yoshiro Nakamatsu, a Japanese inventor. He claims to have created it as early as 1950 but was not commercially introduced until 1971. The floppy disk is, according to Webster’s Dictionary, “a flexible removable magnetic disk, typically encased in hard plastic, used for storing data.” It forever changed computing as for the first time, large amounts of data could be easily stored for continuous use. Not only that, but floppy disks were removable and could be transported to a different location, unlike any sort of data device seen before this was invented.

Popular musicians of the 1970s included Elvis Presley and the Jackson 5. Elvis Presley was born on January 8, 1935 in Tupelo, Mississippi. The boy began his musical career in 1954 when he began a recording contract with Sun Records, and he was an international sensation by 1956. In 1970 he was named one of the Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Nation by the United States Jaycees. During this he served in the United States Army. Elvis wrote many popular songs before his death in 1977, including “Falling in Love With You” and “Blue Suede Shoes,” which were both popular in the 1970s. The Jackson 5 is another example of a popular music group from the 1970s. They produced a number of hits, including “I Want You Back” and “ABC.”

The 1970s can take credit for many great movies, some which are still popular today. A few examples of timeless 1970s films are Star Wars, which came out in 1977, and Jaws, which came out in 1975. Popular children’s movies from the 1970s include films such as Robin Hood, which came out in 1973, and the Aristocats, which came out in 1970. Popular television shows included M*A*S*H, Charlie’s Angels, and The Brady Bunch. Children could watch shows such as Sesame Street, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and Scooby-Doo Where Are You?. The 1970s saw actors and actresses such as Goldie Hawn and Peter Strauss.

The 1970s saw a menu similar to that of today. Fondue and Jell-o were incredibly popular during this decade. Watergate salad and Watergate cake were popular in the later 1970s after two cookbooks poking fun at the Watergate incident of the early 1970s were published. One of these, The Watergate Cookbook, the Committee to Write the Cookbook, contained recipes such as Nixon’s Perfectly Clear Consommé and Cox’s In-Peach Chicken. Many popular foods were invented in the 1970s as well. In 1970, Hamburger Helper was created, followed by Starbucks in 1975, Pop Rocks in 1976, and Ben and Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream in 1978.

Clothing in the 1970s was very similar to that of the 1960s; no initial fashion revolution occurred during this decade. Many of what people consider to be the best elements of the ’60s drifted into the ’70s, but blended together the styles of mods and hippies. The majority of the 1970s sported the famous wide-legged bell-bottoms, but by the end of the decade, they had almost entirely been replaced by much thinner legged pants. Dresses and tunics were popular for the ladies, but at the same time this was first decade in which women could wear pants for basically every aspect of their lives and have it be seen as proper and acceptable. Sandals or platform shoes were the shoes of choice. While the beginning of the 1970s saw many vibrant colors and intriguing patterns, by the end of the decade they had almost completely disappeared and been replaced by earth tones, grey, and black, as if the people grew tired of the exciting colors they had spent decades enjoying.