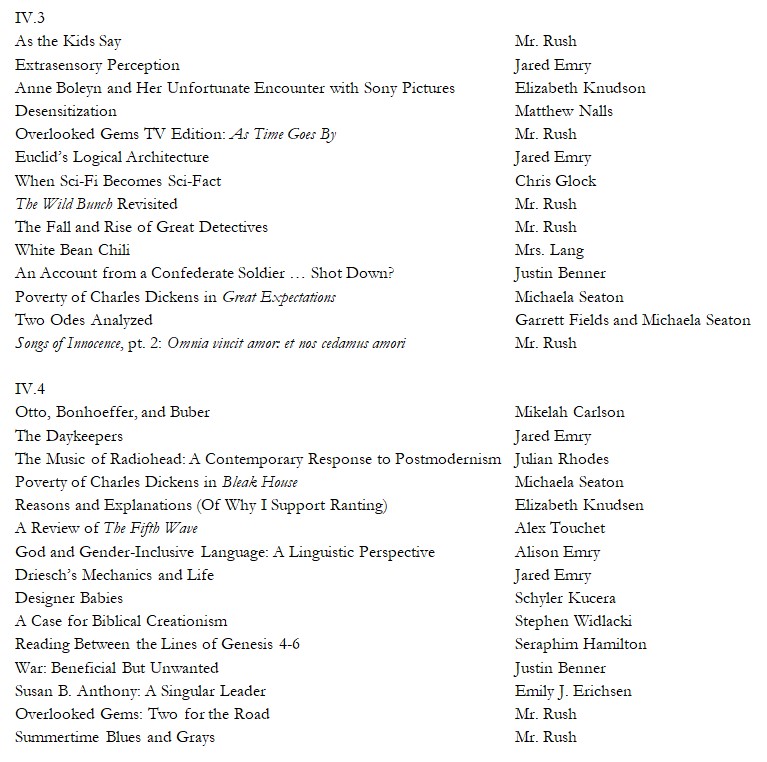

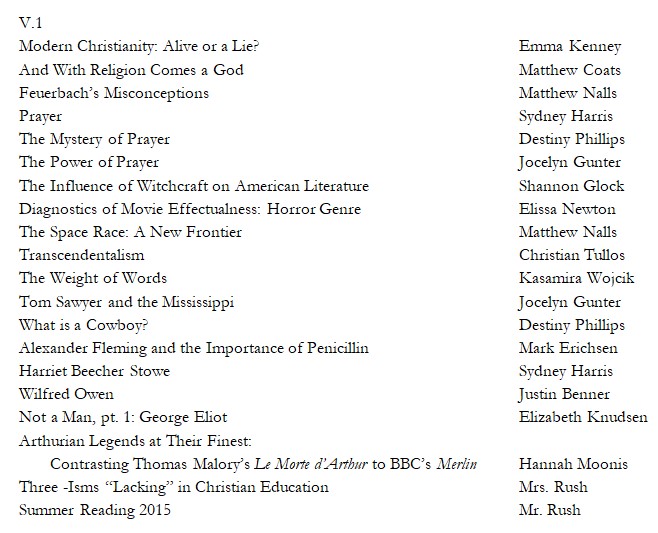

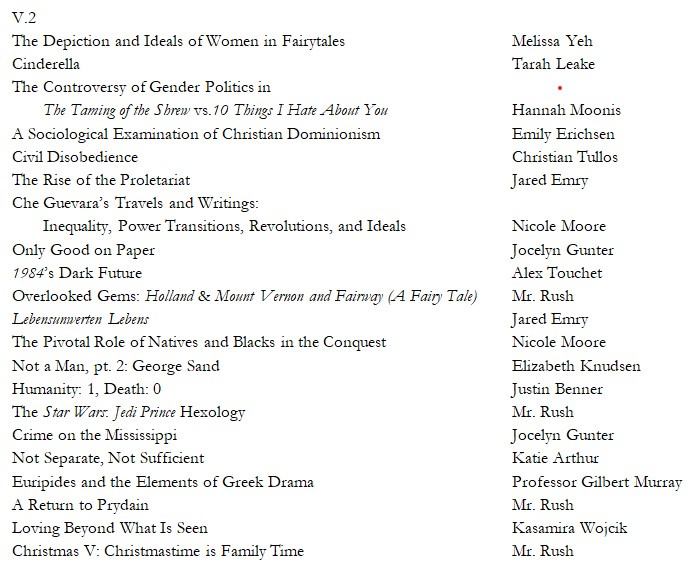

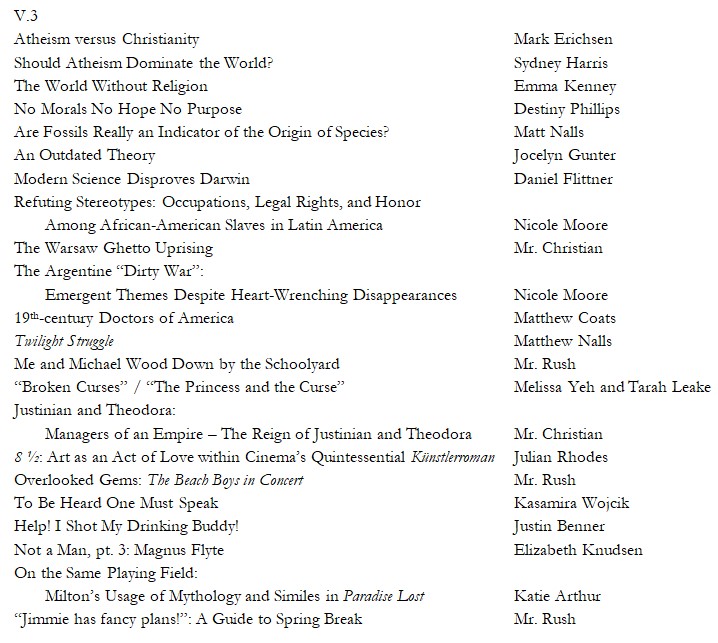

While you are having a fun summer vacation watching top-notch anime series and movies, I am hoping I will be organizing my Star Trek CCG collection. Not that it is in total shambles, mind you. Just because I haven’t played the game since Hanson was on the charts doesn’t mean my Star Trek CCG collection is in disrepair. What I mean is ever since the summer of 2015 I’ve felt like taking inventory of what I have, what I don’t have, investigating what it may take to fill in some of those gaps, and, ideally, actually play the game again. Despite popular opinion, I don’t really enjoy acquiring things just to have them: I do want to read the books I own, I do want to play the games I own, I do want to watch the digital video discs I own, et cetera. I’m not big on just having objects in my home just for the purported joy of ownership. It’s all God’s anyway, right?

I have no false hopes the electronic-bay will suddenly get giddy for my extras: “oh, you have 121 ‘Anaphasic Organism’s? Here’s a bajillion dollars!” I doubt I could get a ha’penny for all my “Anaphasic Organism”s, “Archer”s, “Phaser”s, et cetera put together. I’m sure the world has no need for my commons. Nor do I have any designs on selling my rares (no one ever believed the “I.K.C. Pagh” was “rare”). I’m not trying to get back the, shall we say, hefty amount of money that was paid for this decent-sized collection (I admit wholeheartedly my parents paid for most of it). I just want to know what I have.

Then I want to give most of it away. Are you interested?

I can tell you now it’s all 1st-edition stuff, basically up to Deep Space Nine and a bit beyond. It’s been awhile since I’ve really looked into the game, not counting a few dormancy-ending days last summer, so I’m not sure what I’m missing as far as what sets I have none of in the 1st edition. I’m hoping my brother will be able to get a few boxes of packs or whatnot at GenCon this year, maybe even dabbling in 2nd edition, but we’ll see. This past Christmas, my dad got us a box of Marvel Dice Masters booster packs, and Julia and Ethan and I had a good deal of fun opening them, seeing what cards and dice came in the packs, and then I had a swell time organizing it all, seeing what was missing, what we got … and all the fun of opening CCG packs back in the ’90s came back to me.

Coming from a long line of librarians, or a short line depending on your angle, organizing must be in my blood. Like, possibly, most who grew up in the CCG age, I spent a lot more time organizing, bindering, listing, organizing, and deckmaking than I spent actually playing the game. I’ve already told you the story of how I got the ultra-rare “Future Enterprise” card from a 97-cent discount pack from WaldenBooks my mom got me one summer afternoon, and how she got me the limited edition Kivas Fajo Collection as a pick-me-up after I broke my arm (it was only until later, when I grew up a bit, that I found out it is somewhat incongruous to spend a good deal of money for a gift to cheer up someone who just cost you a great deal of money on hospital bills as a consequence for doing what you shouldn’t have been doing in the first place — it must have been love). But that’s part of the fun with CCGs, really: much like Wordsworth’s dual-view of poetry, CCGs are both the overflow of powerful emotions (buying the boosters and seeing what new cards are inside … or more likely what duplicates you got again) and those powerful emotions recollected in tranquility (the calm joys of sorting, organizing, and checking off your growing collection). The only downside is the cost.

And storage. I’m out of storage space. Do you want to help?

Hey, if you come take my duplicates, we could maybe then starting playing the game together. Everyone wins. Give it a thought. Let me know. It’ll be fun.

P.S. — Are you interested in Decipher’s Middle Earth: The Wizards CCG?

P.P.S. — Even if you don’t want any anime or feel like starting your own hand-me-down Star Trek CCG collection, I hope you can come over for the summer gaming days. That may be even more fun.

P.P.P.S. — In any event, we at Redeeming Pandora are very grateful for your loyal readership over the years through all 20 exciting issues. I recently looked at issue 1 … man, we hit the ground running and we have been having a blast ever since. I say “we,” even though most of the team has fluctuated over the years, but the willingness of the ol’ staff to continue contributing, as evidenced in this very issue, has been a genuine delight for me, especially seeing how they have grown and improved after their time with us. Here’s to 20 more issues, faithful reader!

Enjoy your summer!

Remember: “wherever you go, whatever you do, whatever you say … say, say, say … say it with love!”

In addition to the fine recommendation my brother has just given you, I thought I would offer some of my own recommendations for some enjoyable, exciting, moving, and more or less important anime series of note from recent years. In stark contrast to most of the things we recommend here at Redeeming Pandora, these present recommendations are more critically popular than you might expect from us — instead of the overlooked, the obscure, the forgotten, and the ignored, these are some of the most beloved and acclaimed series around. Why, then, the need for such a list, you may wonder? Fair enough query. The thought occurs, while the anime circles out there in life are presently aware of these gems, you perhaps are not. Maybe you’ve been under the impression “anime is just Japanese inappropriateness” or something along those lines. As with all sorts of human endeavors, however, a few extreme examples should not besmirch an entire genre. Just as Grand Theft Auto (for example) should not motivate us to generalize the entire videogame enterprise as horrible, a few of the more saucy anime series out there should not prevent us from enjoying and experiencing the better works the field has to offer. (Either that, or you’ve realized by now all of my articles are worth reading, regardless of subject matter and thus “need” is replaced by “just for giggles” and that’s why you are reading this; for that I thank you.) Here, then, in no particular order, are four series worth watching as you while away the summer waiting for the weather to get deliciously cooler and the skies to get beautifully grayer.

Attack on Titan

I admit at the first this is a violent show. Its “Mature” rating is well-deserved. It’s not as bloodily violent as, say, The Wild Bunch or Fight Club, which we’ve somehow gotten away with recommending at Redeeming Pandora, but its violence is intense and pervasive (if not, shall we say, “conventionally graphic”). The series also is occasionally salty, but not nearly as salty as, say, Tim O’Brien’s important and heartily-recommended work The Things They Carried. It would be fair to say, then, this series is recommended despite its violence and mild saltiness.

What, then, you wonder, makes it commendable? I’m not usually a big “post-apocalyptic world” fan, and Attack on Titan is certainly a post-apocalyptic series. Like many anime series, the main protagonists are youngish characters thrust into a chaotic world in which their worth and contributions must be proved and maintained. Somewhat typically with such tales, the main protagonists lose their parents early on and must struggle to get by before they can grow and fend for themselves. Here come the commendations. What is less typical of such stories is Attack on Titan begins in a post-apocalyptic world that has more or less forgotten it is a post-apocalyptic world. 100 years ago, giant “titans” (10-50-feet tall neutered human-like beings) appeared seemingly out of nowhere and began devouring the human race. Somehow, some of humanity survived long enough to build three huge concentric circular walls around the last vestiges of the race. Humanity adjusts to its present condition, more or less, almost getting used to it, despite the elite cadre of military that periodically forays outside the walls, until one day a 200-foot titan appears and batters a hole in the outermost wall, allowing dozens of seemingly-mindless titans to resume the destruction of mankind. Our heroes are caught in the middle, their lives are turned upside down, and suddenly they must live once again with the threat of the titans.

The majority of the 1-season (as of this writing) show follows our three heroes (Eren Yeager, his foster sister Mikasa Ackerman, and their buddy Armin Arlert) as they make their way to the Military to start taking an active role in the defense of mankind and eventually, hopefully, the reclamation of the planet from the mysterious titans. Eren is a conflicted protagonist, and before too long, as is often the case, he has a special destiny integral to the survival of mankind. Mikasa proves herself as an impressive killing machine, as the military uses impressive technology to fight the giant titans. Armin, though initially suffering from self-confidence issues, soon enough proves himself as a brilliant strategist and scientific mind. Along the way, we meet a number of supporting characters who get very interesting the more we get to know them. The only problem with this, is, since most of them are front-line military against a nearly-invincible and relentless foe, the mortality rate among the supporting cast is high — you can’t get too attached to them, really.

I don’t recommend it for the violence, of course. I recommend it because it is a tense show with a large number of exciting mysteries (where did these titans come from? why is Eren so special?) and twists and turns, combined with the sort of Battlestar Galactica-like “humanity banding together to fight off destruction, all the while exploring what it means to be human and moral and all that good stuff” that makes a show like this much more philosophically satisfying than others of its kind. Sprinkled throughout are engaging battle scenes, heroic sacrifices, intriguing layers of politics and betrayal, poignant quiet moments, revealing flashbacks … and then, suddenly, your jaw will drop, your eyes will bulge, and everything you thought you knew about the series and its characters twists inside out. And then it happens again. And you’ll be hooked.

It is only one season, so far, but feel free to use it to motivate you to read the manga, since that is much further along in the overall storyline than the anime series is thus far (and, naturally, it’s richer in character moments, subplots, and other literary goodies not always translatable to a short television show).

Cowboy Bebop

Considered one of the all-time greats for good reasons, Cowboy Bebop is certainly a worthwhile viewing experience. It, too, is occasionally mature, especially in the dialogue, but its overall presentation, fascinating characters, wholly believable world, philosophical explorations, and diverse musical score all overshadow the sporadic saltiness. It is also a limited series, with only 26 episodes (plus one later mid-story movie), so it doesn’t take a lengthy commitment, but the complete series leaves you with such a positive impression, you are glad you watched it.

In a way, Cowboy Bebop is also a kind of post-apocalyptic series: after a nuclear accident, parts of Earth are uninhabitable, but fortunately we have discovered interstellar gate travel and have colonized and encountered other planets and so we are okay. Sort of. Corruption and basic human nature have followed us into outer space, and since space is a vast place, the major corporations and generally decent folk need bounty hunters (called “cowboys”) to help make the spaceways a better place for all. Two such noble bounty hunters/cowboys aboard their ship Bebop are our heroes for the series: Spike Spiegel and Jet Black. Along the way, they meet new friends, we learn about their old enemies, secrets are uncovered, choices are made, and things will never be the same. And the series is only half over.

It is an impressively dynamic series: some episodes are very dramatic, some are poignant, some are adventurous and funny, some are nerve-wracking — all are high quality. Even the episodes you like least are better than other shows you really like. It’s a very layered show: you have to pay attention to the details, as moments and cameos in one episode will come back a couple episodes later. This adds to the overall heft of the series as well as encourages you to watch it again and again. Additionally, it’s a very rich world: the corporations, the supporting characters, the layers of past and present all imbricate in top-notch ways. I know I’m starting to recapitulate generally high praise, but this series deserves all the accolades it has garnered and more. I’m not saying it’s my most favorite series of all time (you know what that is already), but this is definitely a contender for anyone’s short list, anime or not. You will enjoy this in deeper, more meaningful ways than just “yeah, I liked it.” It gets you thinking about a whole lot of important ideas without coming off as didactic or belabored. I realize this is awfully general, but I really don’t want to spoil too much of anything else, as it’s best enjoyed out of wonder without too many preconceptions or spoilers. It will not disappoint you.

Fate/Zero

This yet-another 26-episode complete series is a prequel to another fairly enjoyable anime series Fate/Stay Night. Fate/Stay Night is a computer/videogame with multiple storylines and directions (as in, the story and characters can change depending on which “track” you choose to follow based on your actions and such). The basic premise in both Fate series is every 60-some years, a Holy Grail (not necessarily the Holy Grail) appears on Earth to give one worthy mage and his/her Heroic Spirit companion a wish. Before this can happen, several want-to-be-worthy mages each summon a Heroic Spirit (famous person from history) to beat the other competitors in a Street Fighter/Moral Kombat-like battle to the death. Thus, this series, too, is a bit mature at times. (The main and obvious villain of the series is horrifically villainous — you will immediately be rooting against him and his sheer evil.)

The first half of the series introduces the main combatants, their historical Heroic Spirit counterparts, their goals, their wishes, their conflicts, and a whole lot of other interesting notions (such as the families and mystical secret organizations involved in the centuries of these Grail Wars … secret cabals that make the Illuminati seem like the Boy Scouts of America). The protagonist of the series, Emiya Kiritsugu, is very layered, as are almost all the characters. My favorite duo is mage Waver Velvet and his companion Alexander the Great. Their scenes are among the best of the series, which is saying a lot, considering how good the series is.

Since the mages have called upon Heroic Spirits (except the villain of the series has conjured up a truly heinous person of history), one of the intriguing themes of the series is honor in its many forms: how to achieve it, how it can be lost, can it be regained? and all that. Our main protagonist, who has a checkered past at best, is aligned with King Arthur, as truly a noble historical figure as possible (though there’s a pretty big twist I don’t want to spoil for you here). Their interactions are likewise engaging. These heroes, being noble, often struggle with the need to eliminate each other during the grail contest, even though they know they are in effect servants of the grail until they win it and gain their deepest wish.

Since it’s a prequel to a story/series that was made years before, the ending is likely well-known and necessary. I’m usually in favor of reading/seeing things in the order in which they were made and not their in-world chronological order (my thoughts on the proper order of The Chronicles of Narnia are well known), but I don’t know if watching Fate/Stay Night is better, especially since I experienced Fate/Zero first. I certainly think it’s worth watching Fate/Stay Night as well, but it is very much a more typical “young teens are the heroes to save the world” sort of story, whereas Fate/Zero is definitely a grown-up series (the kids of the characters in Fate/Zero are most of the main characters in Fate/Stay Night, 20-years later instead of the usual 60).

Don’t let the “mages conjuring heroes of the past” put you off. The only off-putting thing is the main villain, but he is so obviously heinous all the other characters rally around the rightness of getting rid of him. Fate/Zero is a great story of nobility, sacrifice, redemption, heroism, and much more.

Fullmetal Alchemist/FMA: Brotherhood

Some may say I’ve saved the best for last, but that may be tainted by the fact Fullmetal Alchemist is much longer than the other series listed here, with 50-some episodes in the first series and 60-some in the “reboot-like” series Brotherhood. The length of the series naturally lends itself to deep, thorough plots, well-rounded and beloved supporting characters, meaningful conflicts and resolutions, and all the things that make an adventure television series great.

Edward and Alphonse Elric lose their mom when they are still fairly young (you can see a trend among this series), but instead of accepting her mortality they use their alchemy skills to try to bring her back to life. It does not go well. Alphonse loses his body; Edward loses his arm and leg while attempting to save Alphonse’s soul, attaching it to a giant suit of armor. Their childhood friend, Winry Rockbell, creates a new arm and leg for him. (This is all the first minute of the first episode, so I’m not spoiling anything.) Having survived such an experience, the brothers realize they need to improve their alchemy skills and find some way to get Alphonse’s body back. Thus begins their journey.

As with all of these, a great deal of the enjoyment of the series comes in the diverse supporting cast, the ups and downs of their journey, and the growing menace of the behind-the-scenes puppet masters, as well as the philosophical quandaries the Elric brothers encounter along their journey. Having violated one of the key laws of alchemy (don’t attempt human transformation), the Elric brothers begin on the outs, even as they subordinate themselves to the Military (yeah, I know, it seems to have a lot of similarities to Attack on Titan, but they are radically different stories) in an effort to gain access to more knowledge about alchemy, perhaps even tracking down the elusive Philosopher’s Stone. Edward meets several other dubious alchemy users (sort of how Huck Finn meets other likeminded characters warning him against living this sort of life), and he is often tested in how he will live and use his powers: has he learned his lesson? is he committed to others? or is “accomplishing their goals” the only value worth embracing, regardless of who is affected? It’s a very rich show.

Without giving too much away, I’ll comment on two engaging aspects of these series. First, one of the main group of antagonists are named after the Seven Deadly Sins. Though some characters in the two series represent different Sins (e.g., “Dave” is Pride in FMA but Envy in Brotherhood), they make for a very menacing and thought-provoking group of antagonists. Second, unlike almost every American show, the heroic adults of both versions of the show recognize their need to help the Elric brothers since they are young boys and vocalize their responsibility as adults to help and lead the boys as trustworthy adults. Instead of American shows that tell us children are smarter than their parents and other authority figures, Fullmetal Alchemist enjoins us as adults to live exemplary lives to lead the youth for the good of all considered, and children should allow the trustworthy adults in their lives to protect and care for them when it’s the right thing for them to do.

I definitely recommend watching the entirety of the original series first, even though soon enough the two series become drastically different. The first Fullmetal Alchemist began before the manga wrapped up, and thus it started telling its own story about halfway through. Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood (as it’s known here in the U.S.) follows the manga more closely (so I’m told — I haven’t read it yet). I agree with those who find the ending of Brotherhood more satisfactory than the ending of the original (even with the original’s post-series wrap-up movie The Conquerer of Shambhala), but the original’s story and the fate of many supporting characters is satisfying as well. I’ll probably write a more detailed article about this idea next year, once you’ve had time this summer to watch both series.

There you have it. Four high-quality anime series to lead you into what may be a fresh genre of television enjoyment and life improvement. Have a good summer of watching great series! (It’s a great way to avoid sunburns, at least.)

The Hayao Miyazaki oeuvre covers so many beloved classics of anime such as My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Princess Mononoke. Often overlooked is his very first film directorial effort, The Castle of Cagliostro. It’s not hard to see why: it doesn’t quite fit with the themes and elements that characterize much of the rest of his work. There isn’t a young girl protagonist, no moving to a new country home, no emphasis on the importance of preserving nature. Instead, we have a film that is part of a different large body of work, specifically the Lupin the Third series by Monkey Punch, an anime series Miyazaki himself worked on. But let me tell you right now, The Castle of Cagliostro is not merely my favorite animated film of all time, but also in my top three movies (live action or animated) ever.

You see, Castle of Cagliostro has what I like in movies on a base, visceral level: excitement, adventure, and really wild things. Castle of Cagliostro starts with a Monaco casino heist at the height of conflict, our “heroes” Lupin and Jigen running away from the police with arms stuffed so overly full of cash bills stream behind them as they impossibly hurdle over obstacles on their way to their getaway vehicle. The police bumble their way into their own vehicles, which proceed to fall apart in spectacular and equally impossible ways: splitting down the middle, wheels flying off, crunching to a halt after moving mere inches — all of these the product of sabotage by Lupin, as revealed by his taunting note left on the engine compartment of one of the now-useless cars.

This illustrates what is the true hallmark of this movie: portraying a thrilling adventure where the rules of physics shall bend beyond that of reality, but only in ways that enhance the thrills and humor without destroying important dramatic tension. The most obvious example of this is my favorite sequence of the film, a car chase around a winding cliff path with Lupin and Jigen trying to intercede on behalf of a woman being chased by some thugs. At one point in this tense chase, Lupin drives his Fiat 500 (a ridiculous car to even be in such a chase) sideways up the side of the cliff. It’s completely mad, but just wonderful to watch. Yet while physics have been defied, dramatic tension remains — we are still worried for the well being of the woman in the pursued car, as it creeps toward falling off a cliff. Even in later action sequences we still hold our breath, hoping our hero can make it through.

This says nothing of the lavish setting of the movie, where even on his limited budget Miyazaki fills the fictional Grand Duchy of Cagliostro with detail and intricacies. Miyazaki’s love of visual landscapes packed with wonders to explore can be seen even here in his earliest directorial work. There are more than a few long, lingering shots that may not move the plot forward but help immerse you in this little independent city-state where most of the movie takes place.

But of course, we need to address the 500-pound gorilla in the room: can you enjoy The Castle of Cagliostro without knowing a lick about Lupin the Third? Honestly, it’s actually ideal not to have preconceived notions of the Lupin characters. On its initial release in the late seventies, The Castle of Cagliostro was actually criticized for its portrayal of the beloved Lupin the Third characters. For instance, Miyazaki’s Lupin is far more heroic and less arrogant, and his treatment of female lead Fujiko Mine gives her depth and skill as opposed to being a sex object. Miyazaki makes these characters his own, and the movie is better for it. You get all the needed history in the film itself, from Lupin and Fujiko’s mutual admiration to the complex relationship of Lupin and his law enforcement foil Koichi Zenigata.

The Castle of Cagliostro has also stood the test of time for me, personally. As one of the three movies I will pop on the TV whenever I truly need a pick-me-up, it has never failed to put a smile on my face. I have watched it dozens of times, only rivalled in number by the other members of my movie holy trilogy (Jaws and Shaun of the Dead), and it is always the right choice to watch. It is my favorite anime of any sort, movie or series, and you absolutely should give it a try.

There are many different reasons why female authors have chosen to take male pennames. In years past, the reason was political. Authors like Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot) wrote under a male name to ensure their more political novels were taken seriously in an era when women’s rights were practically nonexistent. Other reasons were due to great influence by male authors and the desire to imitate them. An example of this is Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin (George Sand). In more modern times, female authors have still felt they had to write under a male pseudonym to ensure their books were accepted by the male audience, such as Christina Lynch and Meg Howrey (Magnus Flyte). This final essay explores yet another reason a female writer to write under a male pseudonym.

Robert Galbraith is the author of the Comoran Strike series, which presently consists of three books: The Cuckoo’s Calling, The Silkworm, and Career of Evil. It is widely known, however, this award-winning author is not an old war veteran after all, but a pseudonym for J.K. Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter series.

Joanne Rowling was born in July 1965 at Yate General Hospital in England and grew up in Chepstow, Gwent, where she went to Wyedean Comprehensive. She left Chepstow for Exeter University, where she earned a French and Classics degree. She then moved to London and worked as a researcher at Amnesty International among other jobs. The Harry Potter series began during a delayed Manchester to London King’s Cross train journey, and during the next five years, outlined the plots for each book and began writing the first novel. Jo then moved to northern Portugal, where she taught English as a foreign language. She married in October 1992 and gave birth to a daughter, Jessica, in 1993. When the marriage ended, she and Jessica returned to the UK to live in Edinburgh, where Harry Potter & the Philosopher’s Stone was eventually completed. The book was first published by Bloomsbury Children’s Books in June 1997, under the name J.K. Rowling. Her initials were used instead of her full name because her publisher thought a female author would deter the target audience (young boys) from reading the books.

As is known, the Harry Potter series was wildly successful, having sold over 450 million copies in 69 languages. So why then, at the height of her success, would J.K. Rowling write under a male pseudonym?

According to the author herself:

To begin with I was yearning to go back to the beginning of a writing career in this new genre, to work without hype or expectation and to receive totally unvarnished feedback. It was a fantastic experience and I only wish it could have gone on longer than it did. I was grateful at the time for all the feedback from publishers and readers, and for some great reviews. Being Robert Galbraith was all about the work, which is my favorite part of being a writer. Now that my cover has been blown, I plan to continue to write as Robert to keep the distinction from other writing and because I rather enjoy having another persona.

J.K. Rowling wrote under a male pseudonym in order to receive unbiased feedback. This is something to be respected. She didn’t use a penname under some illusion her books wouldn’t sell because she was a woman; she wanted to start again. And her books sold with or without the disguise.

In previous eras, the reasoning for male pseudonyms may have been political, but today more often than not women do it just because. And that’s encouraging. Social justice has come a long way, and now women don’t have to pretend they’re men in order to have their political opinions heard and valued.

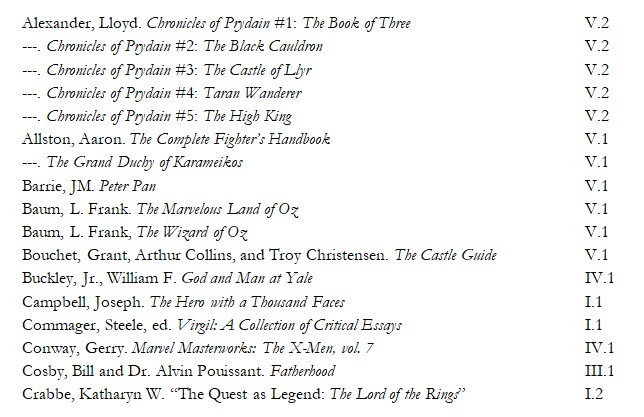

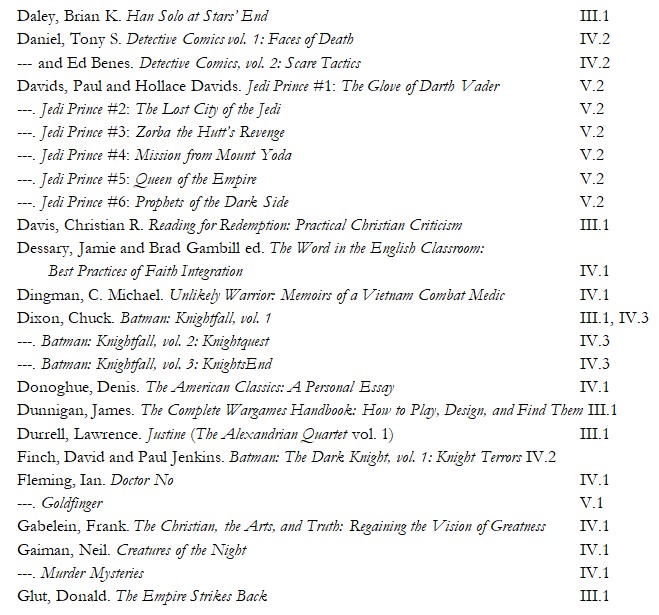

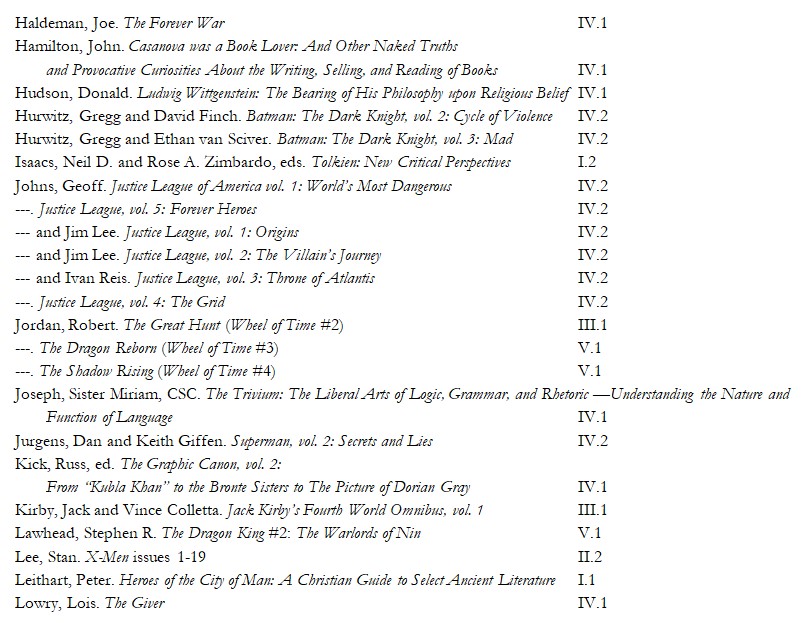

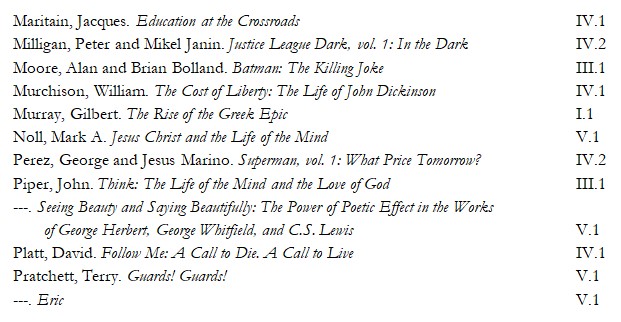

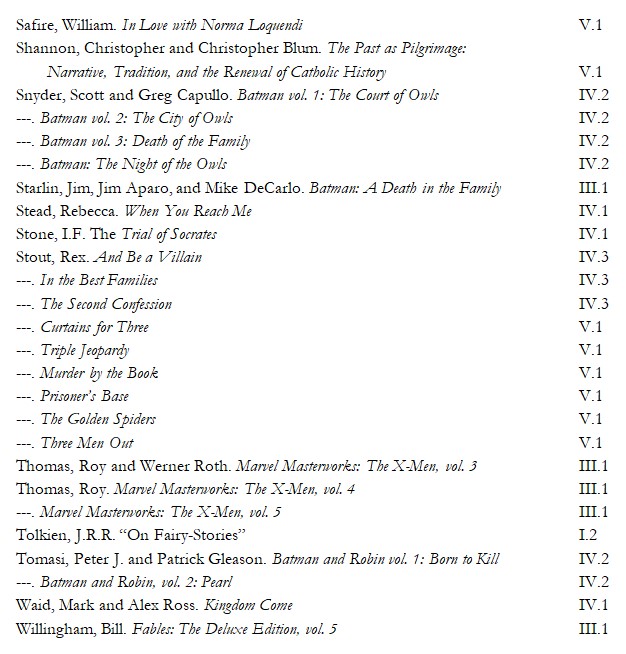

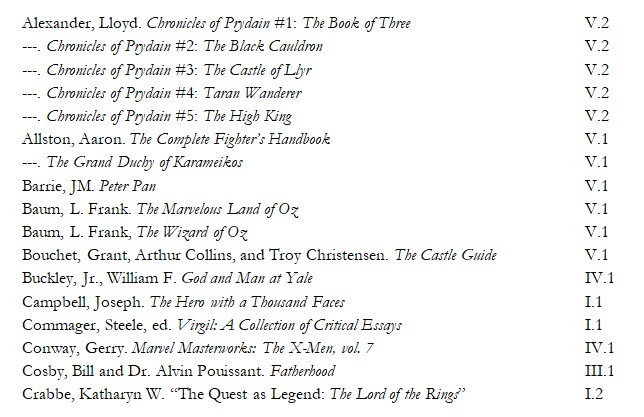

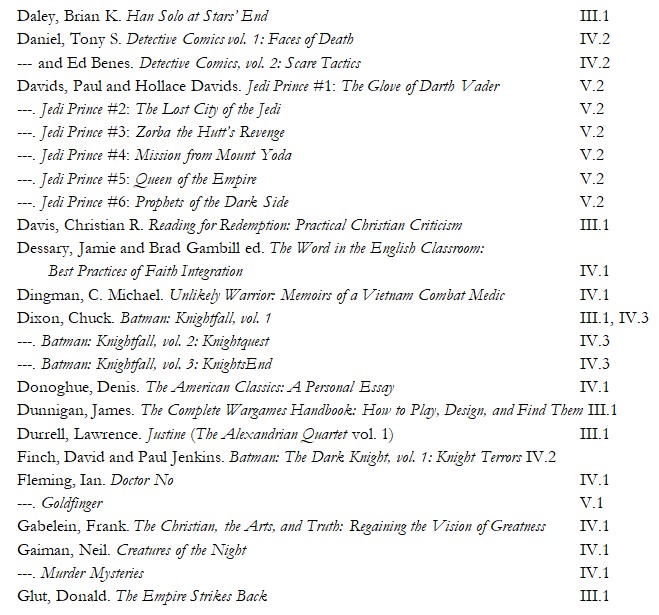

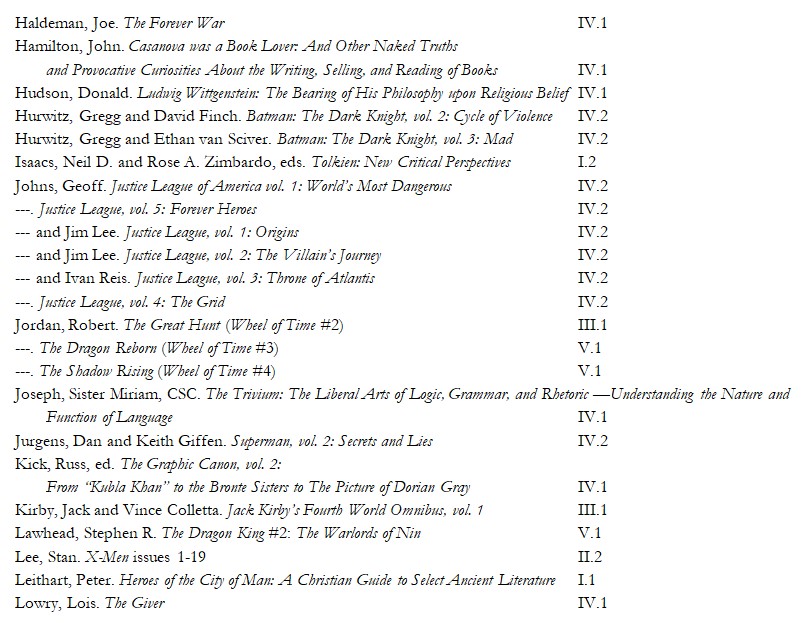

Bibliography

Rowling, Joanne. J.K. Rowling. N.p., 2012. Web. 18 May 2016. <www.jkrowling.com/en_GB/#/about-jk-rowling>.

—. Robert Galbraith. N.p., 2014. Web. 18 May 2016. <robert-galbraith.com/about/>.

H. G. Wells was one of the singular most formative authors in the genre of science fiction. Wells was among the first of authors to introduce the concept of a “time machine” to popular literature; he even coined the term. The Time Machine, written in 1895, stands apart from other novels of its time as one of the most innovative pieces of literature of its time. The novel’s importance does not come only from its scientific imagining, but the themes presented along with it. H. G. Wells offered his era much more than mere scientific dime novels.

The Time Machine introduced multiple dystopian ideas in a time where literature was often saturated with utopian themes. For example, people such as Edward Bellamy were writing novels such as Looking Backward: 2000–1887 and Equality in the 19th century: these books were very Marxist in nature and often focused on the proposed dangers of capitalism in society versus the success of socialist strategy. H. G. Wells did not take this route when writing his first novel. When his protagonist the Time Traveler travels forward into the future and encounters a strange society filled with shallow and complacent beings, it seems Wells is taking the utopian route. When night falls, however, the Time Traveler discovers the truth of the society he has landed in, and it is far from utopian.

Wells seemed to have some disregard for the utopian presentations of reality prevalent in other literature at the time. He did not write this story to have a happy ending. In fact, it seems rather tragic. The Time Traveler’s adventure does not bring him to a glistening society in which people live together in perfect community, bolstered by technology. Instead, he discovers a primeval food chain where a caricatured “upper class” is juxtaposed against nocturnal ape-like creatures that feast on their flesh. He travels to the literal end of the world, and instead of returning to his time to warn humanity of its impending fate, he disappears from his time. H.G. Wells was not writing to convey wishful fairytales, but to demonstrate what he believed to be the reality of human society. Many of his early works may be described as almost pessimistic (The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds) in the same manner The Time Machine seems to be.

H.G. Wells was one of the greatest science fiction authors not only because of the revolutionary ideas he presented, but also because of the themes he channeled through his novels. His books were formative to the earliest era of science fiction, and his creation of the term “time machine” spawned countless stories revolving around the theme of time travel. Few authors would be able to say they were the creator of a common literary trope, but H.G. Wells is among the privileged who can.

On October 25, 1854 during the Crimean War the Battle of Balaclava was part of the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855). This indecisive military engagement of the Crimean War is best known as the inspiration of the English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade.” In this battle, the Russians failed to capture Balaklava, the Black Sea supply port of the British, French, and Turkish forces in the southern Crimea; but the British lost control of their best supply road connecting Balaklava with the heights above Sevastopol, the major Russian naval center under siege.

Early in the battle the Russians occupied the Fedyukhin and the Vorontsov heights, bounding a valley near Balaklava, but they were prevented from taking the town by General Sir James Scarlett’s Heavy Brigade and by Sir Colin Campbell’s 93rd Highlanders, who beat off two Russian cavalry advances. Lord Raglan and his British staff, based on the heights above Sevastopol, however, observed the Russians removing guns from the captured artillery posts on the Vorontsov heights and sent orders to the Light Brigade to disrupt them. The final order became confused, however, and the brigade, led by Lord Cardigan, swept down the valley between the heights rather than toward the isolated Russians on the heights. The battle ended with the loss of 40 percent of the Light Brigade.

This poem is an extremely popular poem. It has been featured in The Blind Side, and was even published in the newspaper after being written. Written shortly after the battle, it outlines one of the biggest military failures for the British.

Half a league half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred:

“Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns” he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

Tennyson starts at the beginning with the order to charge. “Half a league” in modern terms equates to about 1.25 miles. So the poem starts out by ordering the 600-man Light Brigade to charge the guns a little over a mile away. Tennyson uses Biblical allusions to bring home the sacrifice made by the soldiers by stating “the valley of death.” This is from the Psalm 23, which says: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.” Clearly there is no belief these men will return from this charge alive.

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismay’d?

Not tho’ the soldier knew

Some one had blunder’d:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do & die,

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

This is perhaps the most famous section of the poem. Tennyson starts with a question asking if anyone was dismayed. Not just that, but if anyone thought someone had blundered: clearly there must be some mistake, sending a light brigade to go fight a heavy artillery position over a mile away through a dead man zone makes no sense. One part of this stanza often misquoted is “Theirs but to do and die.” Often people say “to do OR die,” but this gives a totally different and wrong meaning. Tennyson used “to do and die” to show the troops, even in the face of certain death and blunder, will charge for King and country. By saying “to do or die,” you essentially take away the belief they will actually charge. Not only did the light brigade charge, they didn’t question it, or even try to reason themselves out of it; they simply heard the order and went. This takes an extremely large amount of courage and valor.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley’d & thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Flash’d all their sabres bare,

Flash’d as they turn’d in air

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army while

All the world wonder’d:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro’ the line they broke;

Cossack & Russian

Reel’d from the sabre-stroke,

Shatter’d & sunder’d.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

The next two stanzas give a lot of detail on the actual charge itself. We see in the third stanza they are literally surrounded on all sides by cannons. They are being shot at and losing men rapidly, but even with all the odds stacked against them they rode on through the valley of death. It is interesting he uses the terms “jaws of death” and then “into the mouth of hell.” This is another Bible reference this time to Isaiah 5:14: “Therefore death expands its jaws, opening wide its mouth; into it will descend their nobles and masses with all their brawlers and revelers.” He is saying death will literally eat them alive. In stanza 4 we begin to see them draw their swords and begin to reach the line of cannons. Tennyson states they charged while all the world wondered, basically showing no one knew why they charged into a death trap. After they broke through the lines, there was a fight between the Russian Cossacks and the British light brigade. From the last line we can see the Cossacks retreat but not the light brigade.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

While horse & hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro’ the jaws of Death,

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

“When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!”

All the world wonder’d.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

In stanza 4 we see the immediate aftermath of the skirmish between the Cossacks and the British cavalry. They fought through the far line of the Russian cannons and fought their way out of the jaws of death. The charge amazingly did not wipe out the light brigade but did inflict massive casualties. Most of the force was either dead or wounded. Tennyson wants us to honor the bravery of the 600. They willingly sacrificed themselves on a mistaken order without question.