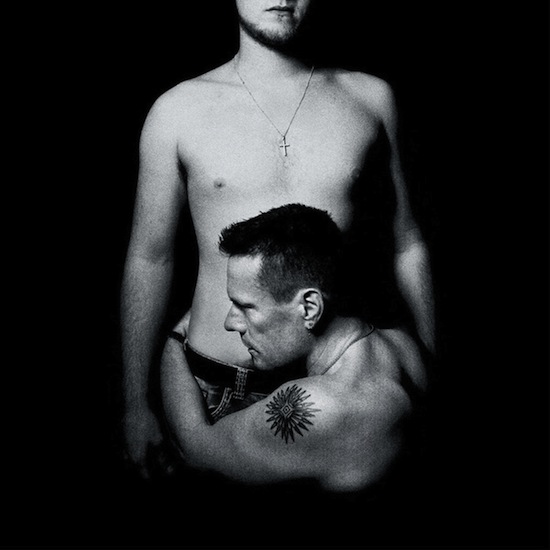

Christopher Rush

Having listened to this album a number of times in the last few months, I can assure you it is a much better album than you probably think it is. In its way, it is superior to even The Joshua Tree and possibly Achtung Baby, keeping in mind “its way” is its ultra-personal nature. It is a wholly introspective, open window into the making of these men and their musical influences, possibly the most revealing album a band has ever put out, which makes the “self-gratifying and grandiose” palaver spewed out at the album’s unusual release all the more embarrassing to those who served the vitriol. I am not, however, qualified to comment on the historical influences that generated not only this album but the band we have loved for decades, so I do not pretend to comment on them too much. You, the faithful reader, can track them down in various places (I hope, too, my old buddy Steve Stockman will write another book about these recent albums as well). Instead, I will comment on what I think of when I hear these songs (especially in context of other U2 songs and albums) and what (if not the same thing) makes them so good. Without further ado, let us semi-briefly explore these songs.

“The Miracle (Of Joey Ramone)”

Unlike the slow-building openers “Where the Streets Have No Name” or “Zooropa,” “The Miracle” just starts — even more abruptly, really, than “Vertigo” or “Zoo Station” (or any of the others). We feel like we have walked in two seconds after it started, and while that is initially jarring, it fits well with the point of the album. This isn’t The Wall — it doesn’t have to begin with birth and build slowly up to a life story. Boom. Here is the start. Here is the point where the rising action is about to begin. This isn’t season one, episode one; this is season one, episode eighteen, and things are about to change for the better (in some cases).

Much of this album gives us the impression we are re-covering old ground, doing what Frost said is practically impossible, but we are doing it with fresh eyes and fresher ears. The almost pep-rally nature of “The Miracle” is unusual for U2 and brings a lot more energy than we are probably expecting, considering the band isn’t getting any younger and a retracing of one’s roots often has the laconic feeling of Wordsworth not the immediacy of Keats (I should probably say Byron or Shelley, but as we all know Keats is far superior). Even so, this is an energetic song. Retracing their roots has brought that energy the band needed — not merely to remain “relevant” — and this is an energetic album.

The lyrical freshness of the album matches the reinvigorated musical energy. “I was chasing down the days of fear” and “I wanted to be the melody / Above the noise, above the hurt” is as lyrically excellent as “So Cruel,” and you know how much that says. I love that last line of the bridge “And we were pilgrims on our way.” We should have been listening to the albums of U2 as a pilgrimage, shouldn’t we?

I’m not Ramones-knowledgeable enough to know what makes them so beautiful, but I’ve had similar experiences in my intellectual, spiritual, aesthetic pilgrimage to know what is being described so enthusiastically, and I hope you have, too. I also know what it is like to take myself too seriously, and it is especially refreshing this album finds a very good balance in presenting their (sometimes painful) youth and influences seriously while simultaneously commenting on their naïveté with the knowing raised eyebrow of old age (I suspect more of this will come in the companion album Songs of Experience). The self-effacing humor of the pre-bridge is one such knowing raise.

One great element of this album is that self-awareness, manifesting in this instance by the different choruses. After the verses communicate the feeling, the memory, the experience the song is capturing, the choruses often metamorphose from “here’s what we were like” to “here’s what we appreciate better and what you can learn now” ideas. The final chorus of this song is truly great: I, too, “get so many things I don’t deserve.” The thought “All the stolen voices will someday be returned” is as uplifting and enthusiastic eternity-anticipating line as you will ever hear. It usually brings me to tears. It does anticipate “The most beautiful sound I’d ever heard.” It will indeed be beautiful to hear again the voices of those who have been stolen (by death, surely, not by God). That will be a miracle, indeed.

“Every Breaking Wave”

Here is one of the all-time greats. Musically, this is great. Lyrically, great. It’s great. You probably think that’s circular reasoning, and perhaps it is (okay, it is), but this song added to “The Miracle” make for as impressive a 1-2 start to an album as The Joshua Tree. Here is a song concerned with our infatuation with fear, our unwillingness to slough off our uncertainties as if they are comfy blankets, our trepidancy to risk. We are so reticent to acknowledge what we can see, what we know: the waves will keep coming, we don’t have to chase them. Chasing them, trying to control the world and the waves is not the way to succeed at life. It’s that hubris that siphons from us our courage. It’s time to stop futilely chasing after the waves and let them take us. That’s the only way to get where we want to go. The spiritual implications are glaringly obvious.

Lyrically, the inverted word orders at time may be for the rhythm of the phrases, but they add to the weight of maturity undergirding an album that could easily have devolved to self-pastiche. (I hope that doesn’t sound as pretentious as it sounds.) My favorite part is the “I thought I heard the captain’s voice / It’s hard to listen while you preach” section. True, having just read The Tempest twice with two different groups of sophomores, this section about shipwrecks and waves and shores resonates a little more loudly than it might during the summer, but the reminder we can’t hear The Captain when we are trying to give the orders is always a timely reminder. It’s impossible not to love this song.

“California (There Is No End to Love)”

The trademark Bono “oh” gets new life in this album, as remarkable as anything else here. Despite the backlash against their exploration of American music during the Rattle & Hum era, U2 goes where it needs to go, learns what and where it needs to learn, and unashamedly (and less unabashedly than in their less-temperate youth, shall we say) lets us know about it. They aren’t the Beach Boys, but then again the Beach Boys weren’t always the Beach Boys, and California is big enough to influence just about anyone. Just because my brief personal experience of California wasn’t all that great doesn’t mean U2 isn’t allowed to enjoy Zuma or Santa Barbara (or not enjoy it, as may possibly be the case here).

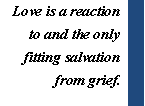

Instead of knowing beauty and truth are (almost) the same thing, it’s likely more significant and efficacious for us to know there is no end to love. Most of the song may give the impression of a light, frothy sort of “love is forever” sort of palliative, despite the revelations of the rather painful experiences couched in the first two verses … until we get to the end of the second verse. It’s one thing to write about and sing about painful experiences — we’ve heard that before (though not as often in U2, not their own painful experiences but certainly Ireland’s pain) — but suddenly the typical “cry in the mirror a lot” notion morphs into a more honest admission “I’ve seen for myself / There’s no end to grief” — and that acknowledgment of man’s prison of grief, eternal if left to himself and his fallen nature, reveals itself as the true basis for why “there is no end to love.” It’s not the simple “I’ve had fun times on the beach, so life is good.” It’s not “we’ve found each other, so love is forever.” Love is a reaction to and the only fitting salvation from grief. Since grief does not end (in this lifetime) love will not end (ever). I don’t know of a more comforting thought, really.

I haven’t quite sussed out the last two lines about stolen days, though I suspect the use of “stolen” is different from the “stolen” in “The Miracle,” since it seems to me we are the ones doing the stealing in “California,” stealing days of happiness and moments of love and joy away from the grief. We certainly don’t want to give those back, and perhaps they are enough, in the end. That makes sense, I suppose.

“Song for Someone”

This is one of those songs if you just listen to it casually once or twice without paying attention to the words you get a very faulty misapprehension of how good it is. That could be said about the entire album, of course. From the first line, whatever “write good lyrics” pills Paul Hewson has been taking in the last five years pays off again. I mentioned “So Cruel” earlier; perhaps this is a companion or sequel, as it is about healing and restoration. We have a great lyrical irony, in that this song purports to be universal (if my assumption about the “someone” being fit for anyone doesn’t take us all to Pleasure Island), though it frequently references private conversations and personal experiences. Again we have the modified chorus trope: the third line in the three choruses is different each time. (I can imagine the uproar if the second version was “with or without” instead of “within or without.”)

The best and worst parts of this song come at the end. The final chorus begins with a wonderful pair of lines: “And I’m a long, long way from your Hill of Cavalry / And I’m a long way from where I was and where I need to be.” I’m not under the impression the “Someone” this whole time has been Jesus … though, come to think of it, that would be totally awesome (and change the meaning of this song drastically). Hold that thought. The second of that pair is a wonderfully honest line about how far Bono has come in his spiritual journey and how far he still has to go — not since October have we heard anything this direct (except “Yahweh,” perhaps).

Now, if the “Someone” is actually Jesus throughout the song, and thus most of the “you”s are also Jesus, that would indeed elevate this song exponentially in both my appreciation for it and, more importantly, its quality. The first two lines of the song don’t seem to fit with that interpretation, though, especially as it would be unthinkable to say to Jesus “my scars are worse than yours, you know.” But then, Jesus does have eyes that can see right through us. He does “let [us] in to a conversation / A conversation only we could make.” He does “break and enter [our] imagination / Whatever’s in there it’s [His] to take” — that fits, too. The last line of verse two, “You were slow to heal but this could be the night,” also doesn’t seem to fit either, however. Also, I don’t know why Jesus would let the light go out, but perhaps the choruses are directed toward us, the audience: the listener is the “you” of the chorus. We can’t always see the light though we should have faith it is always there; we can’t always be the world we want to be; we have the responsibility not to let the light go out. If most of the “you”s are Jesus, the line “If there is a kiss I stole from your mouth” would take us immediately back to “Until the End of the World” and “When Love Comes to Town.” I’m not sure about the whole song, but there’s no denying whose “your Hill of Cavalry” it is. Maybe Jesus is the “someone” the song is for, and we are the “someone” the song is to? Regardless, this is another superb song.

The worst part of the song I alluded to above is only that after this great last version of the chorus (or bridge, maybe), we very much desire one final round of “And this is a song, song for someone,” but we don’t get it. Maybe the live shows.

“Iris (Hold Me Close)”

This song feels like it escaped from The Unforgettable Fire, and since that is one of my favorite U2 albums, that’s clearly not a slight. It’s a lyrically diverse song, even if one is tempted to dismiss it because of the musical sound. Initially I was a bit disappointed by this one, musically, but it does grow on me, especially as I understand the words better. “Iris” plays a few roles in this song, emphasizing the “seeing” theme of the song and possibly being an actual woman named Iris. Of course, once we find out Iris Hewson was Paul’s mom and this is another overtly personal song about Paul’s young life, that part comes into sharper focus. The Freud fans will likely latch on to this notion and interpret the ending refrain as “one needs to free oneself from one’s parents in order to fully become the person one is to be,” but I think it’s more Robert Burns than Freud. As Burns says, if we could see ourselves the way others see us, we would be much more free to be who we should be. And truly, as Christians, we know there is no better (or no other way at all) to be truly free to be ourselves than to be ourselves in Christ. All in all, it’s a very moving song by a man who lost his mom when he was very young, a man letting his mother know she is always with him and possibly wants her to be proud of him. I don’t think there is doubt about that.

“Volcano”

“Volcano” makes you wonder if this album has been locked in some Island vault since the mid-’90s and has suddenly escaped. It’s hard not to find this song somewhat goofy, though its message is important like the rest of the album. This album impresses you the more you learn about it and the influences that have shaped it (again, resources elsewhere can help far better than I can) and the keener one hearkens to the thematic/lyrical motifs strewn throughout multiple numbers. Waves and seas, eyesight and insight, identity, faith and doubt … sure some of those are fairly typical U2 fare, but the intentional lyrical development of certain phrases and ideas in multiple numbers creates an impressive unity to this album easily unnoticed by the casual listener/hearer.

Even with the dangerously goofy dance-techno-like beat of the chorus, which comes dangerously close to undermining the seriousness of the lyrics, the variety within the song works to a good effect, taken as a whole. The “You were alone / … You are rock n roll / You and I are rock n roll” breakdown toward the end gives the song a helpful push to the conclusion the chorus alone wouldn’t have given it, since its (the chorus’s) sound may have been too repetitive to make for a strong enough finish. The basic message seems to be a warning for easily-hotheaded people about the dangers of that, which, while not anywhere close to unique for a message, does not appear all that frequently as a peppy remix-like number. I need to appreciate this song more than I currently do.

“Raised By Wolves”

U2 has been singing songs about Ireland’s war on terror for about 40 years now, but it has never been so personal as this song. It’s a straightforward song for the most part, though it does have some lyrically impressive lines (“My body’s not a canvas” … “Boy sees a father crushed under the weight / Of a cross in a passion where the passion is hate”). The bridge, “I don’t believe anymore / I don’t believe anymore,” is for me the most inscrutable section of this song. If it is about young Paul Hewson rejecting the faith that has brought about (supposedly) these sorts of things, that’s understandable, though that doesn’t seem to mesh with the history of U2’s music (especially with “I Will Follow” and October coming closer to this life experience than War, and War, we must remember, ends with “40”). If it is older Paul Hewson not believing in something, that is even less credible. I just don’t get it yet, but that’s not a bad thing.

The chorus is likewise thought provoking, partly because I don’t have a good grasp of it, either. Musically, it’s an edgy song, certainly the edgiest political song since “Love and Peace or Else,” and that edginess makes the song. The way Bono sings the chorus is also a highlight of the song. I suspect the line “Raised by wolves” is a negative thing, if it is a comment on how his generation was led/affected/burdened by the terrorism and conflict (certainly he is not referring to his own parents or any of the band’s parents, since they have always been open about the tremendous support their families always showed them). But the next line “Stronger than fear” presents itself as a positive thing, as far as I can tell. Then the final two lines, “If I open my eyes, / You disappear” return to a negative idea. It’s another song that would improve with understanding its origins, but it is also translucent enough to assure us of its quality, even if its full meaning is immediately opaque.

“Cedarwood Road”

Another overt homage to friends and experiences of their youth, though this time the overall impression almost dares us to consider it positive, despite being replete with echoes of bombings and loss and pain from the previous song (again, the continuity and overlapping and motif spreading throughout the album snowballs our appreciation for this album the more we grasp it). Guggi is one of Bono’s lifelong friends, a fellow survivor of those dark times, though he didn’t survive quite so successfully.

The music of this song is perhaps its most noteworthy component, so to speak. Say what you will about The Edge, and I’m sure you will, he can still come up with some catchy, integral licks (“The Miracle” has some catchy riffs, too). They only seem familiar because he makes them fit so well.

This is an album of great song endings (even if I think “Song for Someone” ends one section too soon). “A heart that is broken / Is a heart that is open” is a fantastic line, though our enthusiasm for it is likely tempered when we remember (to what limited degree we can appreciate it) the great volume of pain that generated its profundity.

“Sleep Like a Baby Tonight”

I don’t have much to say about this song. It has my least favorite line on the album, “Tomorrow dawns like someone else’s suicide.” It has that “Babyface” feel to it, and we jump, not cynically I trust, to a conclusion there is more here than our initial impressions give us, since U2 and lullabies don’t mix. As I’ve said, I haven’t done a whole lot of research, since I wanted this exploration to be mostly my own experiences and reaction, but what little I saw (mostly accidentally) about this song indicated this is about a priest (the kind of priest Alan Moore writes about in V for Vendetta … yeah, that kind of priest).

Does that make this a bad song? Certainly not. Unpleasant? Perhaps. Is it a social problem we should know about, do something about, bring to an end? Certainly. Musically, it’s another impressive stretch for a band most people likely thought had run out of ideas, even if it reminds us of an earlier song. Bono’s falsetto gets a healthy workout once again, another facet of U2 most people likely thought had faded into the mist.

“This Is Where You Can Reach Me Now”

I’m sure you already knew Joe Strummer, to whom this song is dedicated, was The Clash’s front man, telling us this song reflects the influences The Clash had on young U2 back in the day. I’m not as familiar with The Clash (or any in the punk scene, apparently) as I probably should be, but what little I do know makes the sound of this song (and its military theme) wholly believable. It’s a very straightforward song, as far as I can tell, though it’s also highly probably I’m missing out on a great deal of meaningful subtext. It’s also quite likely I’m misinterpreting much of this album, but that has never stopped me before.

“The Troubles”

Another very personal song (yes, we’ve said that eleven times now, I understand), this one is about the pain of abusive relationships and the freedom that comes from escaping it and reaffirming one’s self worth and value. Musically, it’s another impressive stretch for the band. Lyrically, it’s another remarkably courageous display. If the last half of the album is not as “enjoyable” as the first half, it’s only because the honesty and openness make us uncomfortable, not because it’s an inferior half. I’m not a big fan of rehashing my painful memories (though someone should tell that to my subconscious, since it’s a big fan of running that tape about 12x a week) — I doubt I’d have the courage to write almost a dozen songs about some of my positive life-shaping experiences, let alone the negative experiences. Thank you, men. The people who find you “no longer relevant” must have thought the same thing about Don Quixote … and look how well that ended for them.

So there you have it. I like this album a great deal, and I think you should, too. It will definitely go down in U2 history as one of their best. I don’t know how many more albums these four have in them — hopefully we will not have to wait so long for Songs of Experience (considering their recently-announced tour, “The iNNOCENCE & eXPERIENCE Tour,” is purportedly going to focus on Innocence songs one night and Experience songs the following night in pairs, that gives great gusto to our hope). If they release Experience in a year or two, then, a few years later, top it all off with Man, I’d be quite satisfied (though if they can release several albums in the coming decades, that’s fine with me, too).

It holds up to the scrutiny. It is an incredible gift, not just because it was free. I did get the 2-disc deluxe edition for Christmas from my wife, which was a very pleasant surprise. The bonus disc songs, including alternate takes of “The Troubles” and “Sleep Like a Baby Tonight,” while perhaps less “canonical” improve our appreciation of these songs even more (though I haven’t listened to them enough yet to say more). The 30-minute acoustic set is definitely worthwhile, and the otherwise unreleased songs are obviously a must-have for U2 fans (those who don’t get the special Japanese releases, of course).

You probably have this album, whether you wanted it or not. Let’s not rehash that again. Instead, now that you know about it more, give yourself a tremendous boon and listen to it carefully. Soak it in. Embrace the honesty, the openness. Even if you don’t fully interpret everything correctly, as I most assuredly have not done myself, appreciate it for what it is: a superlative album from one of the great bands of all time.

It’s an album about many things, but it is fundamentally an album about love. Don’t chase love like every breaking wave. Let it take you. Love, as we know, conquers all. Let us, too, surrender to love. You’ll be glad you did.