Nicole Moore Sanborn

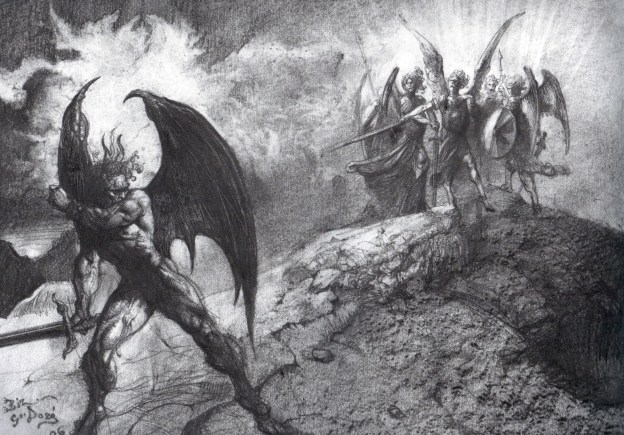

In John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Book 1, Satan and his supporters wind up exiled from heaven, and Satan calls forth his troops. Some believe Satan wields true power in hell after his fall from heaven due to Satan’s empowering rhetoric, the seeming control the demons have over their current situation, and their appearance of having free will. However, due to multiple references made to God’s perfect plan, Satan’s inability to resist God, the defeat of demons, and the difference between free will and power, it is apparent Satan does not wield true power in hell after his fall. Strong cases can be argued for both sides. However, through subtleties in Milton’s writing and the nuances he leaves the reader with throughout Book 1, Milton demonstrates Satan’s power is merely illusory.

Throughout Book 1, both Milton and Satan allude to God’s plan for mankind, thereby demonstrating Satan’s power is merely illusory. These obvious declarations of God’s plan is the primary example proving Satan does not wield true power, as the supporting examples tie in to this. Milton announces his purpose in writing Paradise Lost is to “justify the ways of God to men” (26). Book 1, therefore, demonstrates the ways of God by throwing Satan and his followers out of heaven. While the simple declaration of justifying the ways of God to men does not prove Satan’s power is illusory, Milton uses this declaration to pave the way for more compelling examples. For example, Milton begins to justify God’s ways through declaring Satan and his followers were thrown from heaven because they “transgressed his will,” proving God has power over all (31). This example combined with Milton’s references of man eating the forbidden fruit and needing Christ’s redemption proves God especially has power over transgressors of his will. Satan does not have power over God, proven by God’s preparation and knowledge, as further evidenced where Milton states hell was a place “Eternal Justice had prepared for those rebellious” (70-71). The preparation of hell is a compelling statement illustrating Satan’s lack of power and foreknowledge. If Satan wielded true power, he would have been able to resist God throwing him from heaven. Furthermore, Milton notes paradise, or heaven, was lost to mankind “till one greater Man / Restore us” (3-4). By “greater Man,” Milton means Jesus Christ, the Son of God. Milton’s reference to the restoration of mankind proves God’s foresight over the whole situation, as this example works together with the later declarations of God’s divine power and foresight over Satan attempting to thwart him. The aforementioned qualities of God are juxtaposed to Satan’s lack of control and power.

Some could argue evidence for the argument of Satan wielding power lies in the powerful rhetoric of his speeches, where he gives the other demons hope. Other evidence from his speeches says otherwise, where Satan and Beelzebub recognize God’s power. When these references to God’s power by Satan and Beelzebub are analyzed in relation to God’s overarching plan for mankind, the idea of Satan’s power being illusory becomes evident.

Satan’s uses rhetoric in a fruitless attempt to perpetuate his illusion of power. His misconception of power partially stems from observations of the sheer number of his followers. In discussing the issue of being thrown from heaven, Satan remarks that he “brought along / Innumerable force of spirits armed / That durst dislike his reign, and me preferring” (100-102). Simply because Satan has followers does not mean he has power. Satan attempts to rally his troops by saying, “all is not lost” (106), later realizing the folly of his illusion.

The synthesis of Satan and Beelzebub’s rhetoric further contradicts the idea of Satan wielding true power. Beelzebub says to Satan that he “endangered Heav’ns perpetual King” (131), and Satan refers to God as the “Monarch in Heav’n” (638). Satan and Beelzebub both directly state God’s kingship. Satan’s use of the specific word “perpetual” must be noted here. Since Satan attempted to reign in heaven and failed, thereby only acquiring followers in heaven for a temporary time, his exile from heaven directly contrasts God’s perpetual kingship in heaven. The lines where Satan perpetuates his idea of power are contradictory not only to the truth, as God’s foresight and plan for mankind was proven above, but also contradict later lines where Satan admits God’s power and therefore questions his own. Due to his misapprehension of power, Satan underestimates God’s power. Satan notes God concealed his strength, which “tempted our attempt, and wrought our fall” (642). Here, Satan admits God has more power than him, a realization he doesn’t come to until his exile. Beelzebub also admits God is omnipotent, and his argument is none but the omnipotent could have foiled their plan to thwart heaven (273). God is portrayed as “all powerful,” realized by Satan when he admits God concealed his own strength, especially because Satan mentions (in agreement with Beelzebub) only an almighty power could have thwarted him from overtaking heaven. Clearly, God is almighty in this text, because, by Satan’s logic, if only an almighty power can thwart him, and Satan was thwarted and thrown from heaven into hell, the argument that follows is God is almighty. By Satan’s own logic, he destroys the idea of having power, though he believes in other passages that he has power. Deep down, Satan knows he does not have true power, but will fight God anyway.

Furthermore, Satan’s illusions of power and grandeur caused him to attempt to thwart God, and Milton’s writing demonstrates what a fruitless attempt that was. Beings of power can resist beings of other power, meaning if one truly has power, he should be able to fight someone else with power for at least a small amount of time. Satan could not resist God. Milton states Satan “trusted to have equaled the Most High” (40). This manifests a judgment of Satan through noting his illusions of grandeur of attaining equality with God. Milton declares Satan waged war against heaven “With vain attempt,” an outright statement Satan’s war against God was completely vain and produced no fruitful results (44). That is, produced no fruitful results to the end of Satan gaining equality with God and therefore power over heaven. His fruitless attempt was due to his illusion and “trust” of possessing equality with God. To prove further Satan’s attempt to overthrow God was fruitless, Milton states the “Almighty Power / Hurled headlong flaming” (44-45). Not only did Satan fail to thwart God, God saw this in advance and violently flung Satan from the sky. A few lines later, Satan and his cohorts “lay vanquished” (52). The term “vanquished” connotes an utter destruction of a foe, meaning God did not just win the battle but vanquished Satan. Not only this, but God subjected Satan to a place where there is “torture without end,” torture Satan has no power to change but can only make the most of through acting more evil (67). When Satan attempts to pick himself back up, he observes his number of followers to puff up his own hubris, as referenced earlier.

Satan cannot heal himself, and therefore does not have true power. A striking example of Satan’s illusion of power is after God throws him out of heaven Satan is disfigured. If Satan truly wielded power, he would have been able to heal his face and the lightning would not have altered his appearance. Clearly Satan could not heal himself, because Milton writes “but his face / Deep scars of thunder had intrenched” (600-601). Here, “intrenched” means furrowed. Though Satan still shone and could shape shift, as noted when he stretches himself out in length (609), Satan did not have the power to alter the deep scars God’s power left upon him. This fact also relates back to God’s foresight over the whole situation, because God prepared Christ to restore mankind to heaven and prepared a place for Satan and his followers in hell.

Some would equate free will with power and therefore make the argument that because Satan and his followers have free will, they have power. The question remaining is why God would give Satan and his followers free will without power. However, correlation is not causation here. Free will and power are different things. Satan had the will to fight God in heaven, but his exile proves he did not have power. The demons do have free will, evidenced in their ability to shape shift. Milton says the demons “transform / Oft to the image of a brute” (370-371). The references mentioned above where the demons reference God’s omnipotence must be taken into account. God, in his omnipotence, gave the demons free will and prepared a place in hell for them (70-71). But, God had foresight and prepared a redemption plan for the world (3-4) despite man’s disobedience. God has omnipotence; the demons only have free will.

Despite the fact many demons listed in the catalogues of demons were undefeated, mankind and God were victorious over others, which proves Satan’s idea of power is false. God’s forces did not defeat many demons listed, and some will attempt to use this fact in favor of the argument of Satan wielding power. Among the undefeated demons are Moloch, Baalim and Ashtaroth (plural forms of the male and female gods, respectively), Astoreth, Bimmon, and Belial. While it seems an overwhelming number were not defeated in the text, in the beginning of Book 1 Milton foreshadows a future event involving the “Greater man” who will redeem mankind (3-4) not only from the forces of hell but also from these specific demons. Therefore, by foreshadowing early in Book 1, Milton demonstrates Satan’s power is illusory, despite the later references saying demons gained some power over mankind. Simply because a select few gain power over mankind does not mean Satan has true power over eternity. In favor of Satan’s power being merely illusory, Milton mentions major demons that were defeated by God’s forces. The text states Josiah drove Chemos to hell (418). Chemos was worshipped in Israel and caused lustful orgies. Another catalogue of demons include Osiris, Isis, and Orus, all worshipped in Egypt. The text says “Jehovah…who in one night…equaled with one stroke…all her bleating gods” (487-489). By “equaled” Milton means leveled. Although fewer demons are defeated than worshipped, due to Milton’s foreshadowing of the restoration of mankind and humans thwarting the demons (Josiah) as well as God (Jehovah), the text proves Satan’s power is merely illusory. If his power were real, the demons could not be vanquished and Satan would rule not only on earth but also in heaven.

Satan and his comrades are powerless when matched against God’s almighty power and plan. Although some believe Satan wields true power in hell after his fall from heaven, Satan’s “power” is merely illusory. Through the nuances obtained from reading Satan’s speeches, subtleties in Milton’s writing, and God’s continual display of power, it becomes clear Satan is powerless. Satan will attempt to fulfill his illusions of power and grandeur and attempt to thwart God’s plans, to no avail.