Christopher Rush

Well, here we are again. A third volume of Redeeming Pandora. And they said it wouldn’t last. In this final year of the journal, we thought we’d go all out and make these final four issues as memorable as possible. We’ll hear from some old friends, tie up some loose ends, and keep bringing you eye-opening and heart-warming articles for the rest of our journey together. Here, just in case you were interested, are some of the works I read and reviewed this past summer. I hope you enjoyed the absence of required summer reading this year. I know I did.

Marvel Masterworks: The X-Men, Vol. 3, Roy Thomas and Werner Roth

Roy Thomas starts off his tenure as writer of the X-Men by showing off his knowledge of Marvel history — this could have been a good thing, had he done something interesting with forgotten characters or former X-Men villains. However, he just sort of parades meaningless moments and characters who should have been forgotten and doesn’t do anything spectacular with them. Yes, he does create the Banshee, but he makes him a confusingly-motivated ancient man and needs several tries before he can do something with him. A great deal of the issues in this collection feature a dead-end plot thread of Jean leaving the team to attend Metro College (enrolling during the summer, for no reason). It’s a dead end because Jean usually finds the time to join them on their missions anyway. Despite initially feeling relief she is no longer a fighter, she apparently takes the time to sew new uniforms for everyone and rejoins them anyway. All supporting plot threads that could have been interesting, such as Ted Roberts, Jean’s classmate who suspects the teens are the X-Men, are inexplicably dropped without any resolution. Thomas even brings the Mimic back as a teammate of the X-Men — at Xavier’s request! — but this goes nowhere, despite some good character moments, since after a few issues Thomas has the Mimic lose his powers again. It’s worth reading because it is classic X-Men, and Thomas does manage to get a few good character moments in there (he finally gets the Scott/Jean romance going after a while), but it’s not the best storytelling done in the X-Universe. I read the individual issues, by the way, not the collection named in the title (it’s just easier to call it that for your ease).

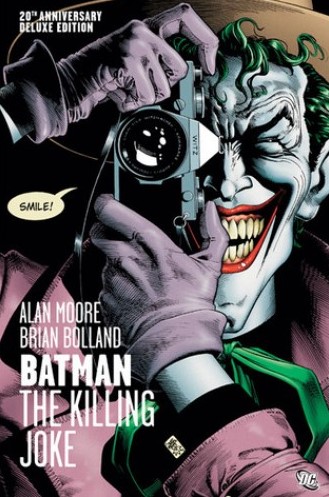

Batman: The Killing Joke, Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

This is not for the faint of heart. Its reputation is well-deserved, even if Alan Moore himself has distanced himself from his work (as is his wont, apparently). Bolland’s artwork abets the grim story in unnerving ways, even without the remastered work in the recent deluxe treatment. The work does not let up in its grotesquery, so don’t read this if you are planning on going to sleep soon. We may never know if this is the real origin of the Joker, which would be all for the best, but it makes frighteningly good sense. It’s short enough to be read in one sitting, which would be the way to go (if you are mature enough to read this). You don’t want to linger, even though it will linger with you for a while. It’s fast-paced, even with the pervasive mix of flashbacks and present-day action, and keeps you gripped, probably more so than any other Batman tale. It’s the Dark Knight at his darkest.

Batman: Knightfall, Vol. 1, Chuck Dixon

Finally, after all this time, it’s come out in a nice TPB and I have read it. Without all the preliminary prologue stuff, non-Batman readers might be a bit lost for a time, such as who Jean Paul is, why Bruce is already beleaguered, when Bane fought Killer Croc, for examples, but it shouldn’t bother people too much. Bane’s origin is dark, but he doesn’t do much except wait throughout the TPB, other than the entire Arkham thing and breaking Bruce Wayne’s back. It’s not nearly as boring as that sounds, since he is a fairly intelligent villain, though the addiction to Venom diminishes him somewhat, since it’s not just about his personal strength and intellect. Anyway, the inevitable backbreaking isn’t the climax of the story, which is more impressive than I thought it might be — the real story is the destruction of Batman, the idea, the symbol. As Bane says toward the end, JP as the new Dark Knight (emphasis on the Dark, not the Knight) does more to destroy Batman than he did, since he just broke Bruce Wayne: turning Batman into no better than the evil he conquers, Jean Paul becomes perhaps a worse nemesis for Bruce Wayne than even Bane is, but we’ll see what happens in part two. The pacing is an odd thing for a 19+-part series, depending on whether you add the non-numbered parts of the story: sometimes issues take place immediately after each other, sometimes days pass, but all of it is fairly rapid in the beginning, following Batman and Robin’s attempts to recapture the inmates from Arkham, though Batman doesn’t treat Robin all that well whether he is Bruce or Jean Paul. Even so, one doesn’t need to pay too much attention to the time factors, since the breakdown of Bruce Wayne is the central idea of volume one, and the creative teams do a fairly fine job with it. The clash of ideas (the nature of good, for example) are highlighted at times, though they take a backseat to the action more often than not, but it’s still a good read that holds up after all these years.

Marvel Masterworks: The X-Men, Vol. 4, Roy Thomas

Unfortunately, Roy Thomas proves himself not very capable of delivering very good stories with these issues. He tries his hand at a major storyline (for the time) with the mysterious Factor Three story, an extended conflict of a mysterious group whose only redeeming value is the introduction of Banshee. Somewhere along the line, Thomas drops the whole “Jean is away at Metro College” thing with no explanation at all, another example of this creative team’s inability to sustain much. At times, Thomas proves he is capable of delivering quite interesting character moments, notably giving Jean a personality for the first time in the series since issue 1. Not only that, but we have the beginning of Jean’s telepathic skills as well, just in time for the startling conclusion in the final issue of this collection: the death of Professor Xavier. The Factor Three main story has some potentially good points, like the “trial” of the X-Men by former foes, but as mentioned above, Thomas never brings the good ideas to successful conclusions. Too often, especially by the end of this collection, Thomas breaks out an inane deus ex machina to finish off the story, often saying the villain was an alien from outer space, destroying all personal interest in the conflicts. This collection also has some of the worst X-Men issues perhaps of all time: the combat with Spider-Man in #35, the Mekano issue in #36, the battle with Frankenstein’s monster in #40 (you read that right), and the utterly inane Grotesk battle in #s 41-42 resulting in the death of Xavier. You know a comic issue is bad when you are longing for the days of El Tigre, the Locust, or even the pirate ship. The new uniforms do nothing for the series other than give Thomas an excuse to stereotype Jean again (despite turning around and giving her one of the best scenes in #42 she’s had since the beginning, as mentioned above). One would think it impossible to make a bad issue starring Spider-Man and the X-Men, but Thomas and Co. somehow managed to do it. All the auguries point to the need for a new creative direction. It is starting to become clear why the X-Men were cancelled.

The Great Hunt (Wheel of Time #2), Robert Jordan

Say what you will about Jordan’s style, he eventually gets around to telling an interest-holding story. Not to say the beginning is boring, since he is creating a rather large world, increasing the cast and conflicts first introduced in The Eye of the World, while adding more layers of time’s repetition as he goes. It’d been a few years since I read TEotW, so I was a bit concerned getting back to the saga whether I would remember enough to make it worthwhile, since starting over would take a fair amount of time; I read some online summaries to refresh my memory, which wasn’t quite as thorough as I thought it was. This was helpful, but Jordan does a pretty good job of reminding his audience of the things worth remembering early on in the first part of The Great Hunt. This was very nice of him, no doubt because his original audience would be reading them a year or two apart as well. There’s a great thickness in these volumes, which makes one think a lot happens, but not much really does in this volume — that’s not a bad thing, though, since he knew he was creating a massive saga occurring essentially at the end of time, just before the Last Battle. He doesn’t have years and years to cover, so a lot of detail happens. Some readers might be put off by this, but if they are, one wonders why they are reading this series in the first place. Jordan didn’t hide the fact he was intentionally recreating a combination of Tolkien, Arthurian Romances, and just about everything else. Knowing that helps enjoy his overt use of myth and archetype — he’s not really trying to say anything new, so readers who get frustrated and say, “oh, that’s just like when that happens in…” are missing the whole point. It’s a slow-building story, but again that’s because it is part 2 of 12/14 — if Jordan just threw every race, every item, every conflict, every character at us all at once, it would be a jumbled mess and not enjoyable. This book was enjoyable, ever more so once I got used again to his style/diction. True, a few threads are left unresolved, again because it is part of a series, but the story is somewhat self-contained even if one hasn’t finished reading TEotW the day before starting this. It has enough twists, turns, and developments to make it an enjoyable read for those willing to take the time to read it.

Fables: The Deluxe Edition, Vol. 5, Bill Willingham

Focusing on characters generally on the periphery to date, the three storylines collected in this edition are rather enjoyable, especially if one has wandered away from the Fables Universe for a while (perhaps mostly waiting, as I am, for the deluxe hardcover editions). Either the language is much more palatable for most of this book or it’s much less noticeable (hopefully the first), which adds to its enjoyment. Time is a sort of tricky thing here, since the first two storylines (the first focusing on Jack, the second on Boy Blue) occur somewhat simultaneously with each other and the previous storyline of Snow and her cubs (seen only briefly here toward the very end of the third storyline collected here). The “rest of the universe” attempt is rather bold — it really didn’t work for Battlestar Galactica, but somehow Willingham pulls it off, perhaps aided by the general familiarity we have with the characters (though that never helps too much with Willingham). It’s nice to see Beauty and the Beast coming into their own, even though it has taken five years (not that we can really tell unless paying close attention). The characters are starting to grow up, which is odd considering it has been hundreds of years since they have been in this plight — perhaps recent events have shaken them out of their comfortable torpor. The third storyline is another clever addition to the Fables Universe, bringing in the Arabian Fables, having been earlier bridged with the return of Mowgli, in a nice touch. It’s a clever story with an ending that works a lot better than the Roy Thomas/Gary Friedrich era of X-Men in the “that’s what you thought” vein. The Adversary is revealed, but that doesn’t help anyone much, allegiances are tested, but as with most endings to the deluxe editions, a kind of peace settles in by the end, ready for the next big thing. Nicely done, this.

Justine (The Alexandria Quartet #1), Lawrence Durrell

Durrell has created an interesting approach to fashioning literature (or at least, followed Joyce and Woolf the way they wanted to be followed): part dream, part memory, part compulsion. It returns to itself quite well, though it doesn’t really lean toward repeated readings, since most readers probably will want to continue on with the series. Just review the beginning again once you’ve gotten to the end and it will be even more impressive. It starts out slowly, sectionally, as if it wants you to take your time in reading it, but that doesn’t help remember it much by the time you get further into the book. Remembering all the characters can also be a bit tricky: Pombal, Pursewarden, Clea, Capodistria, Scobie, Nessim, Memnijian, etc., etc. There’s a large supporting cast, but it’s almost as if you don’t have to pay too much attention, since the focus (when it starts to focus) becomes on the bizarre “love” quadrangle of the main characters (the love is not a real factor in the book, since Durrell is creating a story about human interactions/relationships that are driven by just about everything except love). Durrell’s vocabulary and diction are enticing for much of the book, but stylistically interest comes in waves, receding and gathering. The small sections can work to one’s benefit this way, if the reader perseveres through the middle where Durrell seems to be focusing more on his style than on the content. I understand style was probably his main focus anyway, but it’s almost a bit too thick in the middle. Durrell manages to maintain the style through the entire novel, but he eases up the intensity by the end, making it almost detached (a different kind of detached, since detachment is a key thematic and stylistic marker for the entire book, especially its characters). It wasn’t as gripping as the critics I’ve read make it sound, but that was probably just me. I’m willing to give the rest a try, sooner or later.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, Donald F. Glut

It was interesting finally reading this book. It was much closer to the movie than the first novel, so it was difficult to find too many differences. Some stand out, though: Yoda is a swift-moving blue creature in the book, one notable difference; Leia and Han’s farewell was also different — instead of the iconic “I know,” we have a different exchange, not nearly as memorable. A few of Lando’s lines are different as well, but not too many different scenes exist — on the whole it is, as I said, interesting but not terribly impressive. I’m not sure why a book was made, beyond the usual pecuniary reasons, I suppose. But still, it is classic Star Wars, at a time when the Expanded Universe could fit on one very small shelf, and thus it is worth reading for that reason. The uncertainty of the characters and their destinies are there, and much more “authentic” than in Splinter of the Mind’s Eye. The characterization of Darth Vader is still slightly discrepant, so his comments and motivation for finding Luke are different and intriguing. I still say it would make more sense to say TESB occurs 6 months after ANH, and RotJ takes place 3 years later, unlike what is “officially” recognized. It still doesn’t make sense why 1) Han would wait 3 years to settle his debts with Jabba, 2) Ben would wait 3 years to tell Luke to seek out more Jedi training, 3) Darth Vader would take so long to track down Luke, as experienced as he is in the Force, and 4) the Rebels are only just now setting up shop on Hoth (where have they been in the meantime, why did they need to leave?) at the beginning of the book. If it were only 6 months between the destruction of the Death Star and this, all of that would make a bit more sense. And it would be more conceivable how Luke could become so much stronger in the Force in a few years between Empire and Return, how they could start to infiltrate Jabba’s palace, and how they could get so far on the Death Star without any mention of it in Empire. But that’s just me. It wasn’t a great book, but it was nice to go back to that time in the Star Wars Universe. Things were so much simpler then.

The Complete Wargames Handbook: How to Play, Design, and Find Them, James Dunnigan

This was a pretty good read, though I was hoping it would be better. The subtitle is somewhat misleading: yes, Mr. Dunnigan spends some time talking about how to play, design, and find wargames, but most of the book is him telling us about himself, his work, and the history of wargames (from his perspective). I would have preferred much more time on what the subtitle says, especially playing and designing them, but since Mr. D indicates multiple times only a small select few are smart enough to really understand the math (and thus the essence of the games), he doesn’t really deign to tell us too much more than that. Perhaps he wants us to go back and get all the back issues of S&T and Moves, which will really explain the things he doesn’t want to go into as much. Since he got into wargames because he wanted to analyze history and learn more information, Mr. D takes the position this is really the best reason to get into wargaming — yes, he does emphasize (once in a while) the importance of “fun” (since they are “games”), but it’s not nearly as important to him (and thus, real wargamers) as the historical inquiry and conflict simulation (since that’s the more “proper” term than “wargame”).

Mr. D’s tone throughout, unfortunately, displays this “I’m really smart, most of you aren’t” attitude. When telling us the history of wargames, he gives a backhanded mention of Avalon Hill, doesn’t name Charles S. Roberts at all, then let’s us now he and SPI saved the wargaming industry single-handedly for a decade, until he wanted to move on to bigger and better things, primarily his writing career. Hopefully his other books are better written, but this had a fair amount of typographical errors (perhaps the big need for a revised edition, 10 years later, prevented time for proofreading). In the appendices, Mr. D gives a decent list of other wargaming companies (as of 1992), and even almost gives some respect to AH, but it’s a little late in coming. The computer wargames section, though, does not hold up well. It isn’t even very interesting from a historical perspective, which is rather ironic considering the whole purpose of the book.

I fondly remember the ol’ 386 days and signing on to play games online (well, starting the dialing process, having a sandwich, reading a Michener novel, and then finish signing on and starting to play), but it wasn’t as great as Mr. D makes it out to be (which is not being said from rose-colored contemporary days, since I don’t play computer games today). Obviously, at the time, it seemed incredible, but since he also says the computers were inferior to the strategic capabilities of manual wargames, it’s a rather weird section, almost as if he needs to validate his career choices in shifting to computer games, or at least promoting them. The book is good, though, and he is helpful at times, even if he does repeat himself quite a bit (in the same paragraph, many times) and does talk down at the reader too much (especially for someone who didn’t really want to get into gaming, left it after an admittedly fecund decade, and moved on, sort of). He does give some helpful ideas in playing and designing (though not nearly as much as I had hoped), and it was worth reading, especially for people starting out in (manual) wargames, if any such person exists.

Marvel Masterworks: The X-Men, Vol. 5, Roy Thomas

Again, I only read the X-Men issues separately, not the other issues included in this oop collection. This really shows why the series was cancelled after another year or so — the quality just was not there. Certainly some exceptions exist in this group, thanks solely to the art of Jim Steranko for a couple of issues, and the introduction of Lorna Dane is a great idea, but it’s an idea that doesn’t go anywhere here. Instead, this run is full of ideas that seemed good at the time but ultimately failed: it picks up with the funeral of Xavier, and the letters pages at the time are adamant in the complete, irreversible nature of Xavier’s death (obviously we know how that turned out); this is followed up with the break-up of the team, by the FBI of all people, as if they have some sort of jurisdiction over the team. This is typical of the issues here: potentially fine ideas hampered by illogicalities, inanities, and failed execution. Had the X-Men volunteered to split up, giving the creative team a chance to highlight different characters in a short series, that could have been great — instead, it contradicts decisions already made, goes nowhere, and provides some of the worst stories in the history of the X-Men. Magneto is brought back, supposedly killed off, and brought back again a couple issues later, with henchman Mesmero we’ve never seen before but is apparently Magneto’s life-long acolyte. Juggernaut is brought back for what almost was a confrontation of Marko’s human side and the loss of his step-brother, but this, too, goes nowhere, and the issue devolves into a meaningless battle and an inane deus ex machina ending. This run suffers from a lack of continuity, coming most likely from the great turnover in writers, artists, and decision makers. We see again a fight with the Avengers begun for no reason and ending simply because the issue has run out of panels. It does have some nice moments, oddly enough from Toad, but they are overshadowed by the general shoddy work. Jim Steranko’s work does a good deal to stave off ennui with the series, though once his contributions end, the series immediately plummets to slipshod work again, as if no one was paying attention to the possibilities of quality work. The last X-Men issue features a humdrum battle with Blastaar (who spends most of the issue facing away from the audience) and some of the worst treatment of Jean in the entire series (with Bobby even joking they never should have allowed women to start voting). The series is sadly and definitely on its last legs here in its initial run.

Reading for Redemption: Practical Christian Criticism, Christian R. Davis

For most of this fortunately short (but not quite short enough) book, Mr. Davis’s title is more true than he probably intended. Most of his interpretations in the body of chapters exhibit “reading for” redemption, indeed, almost to the point of “reading in” (as in “reading redemption into the work”). He stretches his case rather thin for some books (especially Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter), and some works he twists out of shape to make fit his pattern (e.g., Ivanhoe). His standards for popularity are also rather bizarre — drawing upon some arcane source of publishing statistics to identify historically popular novels (Tale of Two Cities, Uncle Tom’s Cabin) to see if his particular formula for successful redemptive works fit the past, with varying degrees of success (but since he is doing all of the quantifying, things work or don’t work mainly by his say so). The postmodern/postcolonial works chapter strikes hollow throughout — he is reading for his formula, not for what is there, judging the works by the presence or lack of his criterion. Likewise, the chapter on lyric poetry stretches his ideas rather thinly, which he himself admits, but an admission does not excuse poor treatment of the subject.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of this work is he either expects you, the reader, to be familiar with the works already, or he just doesn’t care if he tells you the ending or reveals the major surprises. Beware: check the table of contents; if you want to read one of the books mentioned without having it spoiled, he will spoil it for you. He rattles off almost all the major plot/character points for each book. It’s one big spoiler alert. Additionally, his diction throughout reminds one of a term paper — perhaps this is his Masters thesis modified into a short nonfiction of semi-criticism. This does not make the work more enjoyable, however; nor do his noncommittal diction and tone (the tone is all “I suggest” this and “please consider” that, though he doesn’t use those specific words too often). I don’t say this to be too disparaging, since he is trying to do something fairly important: returning literary criticism to an important focus, connecting it to what matters in “real life,” too. Mr. Davis does have a fairly good grasp of many topics, as evidenced by his philosophical overviews in the introduction and conclusion. In fact, the introduction, conclusion, and afterword are the best parts of the book. It’s too bad he didn’t just take that sort of tone and approach for his literary explorations in the middle chapters; the book would have been much better.

His survey of Christian criticism in the afterward is again biased by his criteria of successful criticism, and it does seem a very abbreviated survey of Christian criticism, but it’s probably more exposure these other works would get without it, so it’s a fairly nice inclusion. Overall, he does have some good ideas I was glad to read, and his major idea of the necessity of all three parts (creation, fall, redemption) to be a truly real/successful work of literature is a good idea to embrace, but his own application of the theory is a lot of what I try to teach my high school students not to do: mostly plot telling and forcing his theory into the works he addresses. Were this book a sandwich, the bread would be far more digestible than the filling.

Jack Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus, Vol. 1, Jack Kirby and Vince Colletta

Wowzers. It takes Kirby a little while to get going, until we realize it is all part of the plan and remember Kirby is the King for good reasons. Mark Evanier gives us some interesting insight into “the plan,” though, in the afterward: Kirby was planning on giving these new series away shortly after getting them started, ever desiring to create anew. That doesn’t initially sound like a great plan for a new universe with a structured major story arc, but Kirby had a way of making things work, even if no one else around him could understand what he was doing. It is somewhat discouraging to learn this “Fourth World Omnibus” does not have the great finale Kirby planned, once he was committed to telling the story himself (at least Babylon 5 got to tell its tale; Lost as well). What is it about editors, owners, decision makers, and their near-total inability to make the right decision, to use wisely the great talent under them? Pope Julius II tells Michelangelo, “Paint that ceiling.” DC tells Kirby, “No, you can’t finish your mighty epic.” Sci-Fi channel tells Farscape, “Sorry, you can’t have one more season to finish your story.” Honestly. I suppose it makes sense, though, that the really creative people have the basic sense not to go into top business executive levels and stay down at the creative people level. This is a great place to start, since Kirby makes it all new from issue 1 — you don’t really need a familiarity with the DC universe to know who is who or what is what: Kirby makes it all up as he goes. Despite the lack of a specific plan, the King tells some interesting tales. Sure, there’s the Kirbyesque over-the-top dialogue (but, for a story about a world coming and taking over the world, and New Gods usurping the Old Gods, some over-the-top dialogue is necessary), and there’s the seemingly requisite ’70s racism (meet Flippa Dippa, the African-American Newsboy who always wears scuba gear, and Vykin the Black, the Black New God), but they don’t spoil the entire enterprise. It’s quite a ride, and it’s only beginning.

Han Solo at Stars’ End, Brian K. Daley

To really enjoy this, one must try to remember what life was like before the Expanded Universe was large and complicated. I said that earlier for Empire Strikes Back, but it is still true for Brian Daley’s early Han Solo trilogy. Daley’s Han Solo doesn’t sound too much like “our” Han Solo. Like many people who write sci-fi, he doesn’t quite capture the feel, the characters, the universe, and instead makes the characters talk like they would had they been living in the ’70s. This is frustrating and disappointing at times, but if the reader can just acknowledge it and not let it be so much of a distraction, one can appreciate the effort much more. Similarly, it’s not much of a “Star Wars” book, since it has nothing to do with the Force, the Empire, the Rebellion/Republic, or anything beyond the names “Han Solo,” “Chew-bacca,” and “Milennium Falcon.” Yes, Daley has set himself up for that, creating a kind of backstory for Han before he had personally encountered any of those things, so those familiar elements would of necessity be lacking … but that doesn’t make the enjoyment of it any more palpable. By the end, though, it becomes a mildly enjoyable generic science fiction adventure. The final act is decent and even generates some suspense and interest in the ancillary characters Daley has created. It’s not the greatest, but again the circumstances under which it was written were completely unlike today, so sentimentality wins out again here. It’s nice to have it read after carrying it around for 20-some years.

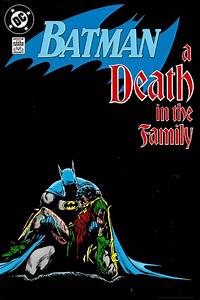

Batman: A Death in the Family, Jim Starlin, Jim Aparo, and Mike DeCarlo

It’s hard to imagine how this story could have gone any other way. As part of DC’s “you decide” campaign to get the audience more involved in the creative process (which rarely ends up as successfully as you want it to be, since, if the fans were really the creative ones, they’d be doing the actual creating themselves), audiences were allowed to call in to vote on the fate of Jason Todd, Robin 2. By a much smaller percentage than I would have thought, the people chose death for Jason Todd. He didn’t seem to be that likable of a character, and he is partly responsible for his own death, but it was still a fairly significant deal to have him killed, even in a universe that kills off and resurrects characters seemingly constantly. Yes, they did eventually bring him back as a villain, but it took several years. Jason Todd can be seen again in the pages of Red Hood and the Outlaws. Jim Starlin does a good job in making even the usually unlikable Todd meet a heartbreaking end, in circumstances making his death much more tragic. With a four-issue storyline, the reader might expect a thorough conclusion, especially since the introduction and development of the story is well detailed. The story, however, just stops. My initial reaction was frustration, since I had put the time into reading the entire arc: I wanted a good resolution, even knowing in advance what the outcome was going to be.

After thinking it over for a time, I realized Starlin did exactly what needed to be done: the Joker/Batman saga never stops. Battles are fought and finished; the war rages on forever. There was no need to “wrap up” the death of Jason Todd, since it would not be something from which Batman could just accept and move on. It remains with him to this day. In this way, Starlin and Co. have crafted a realistic story that resonates with everyone, even if they are not comic book fans. Death is a meaningful, consequential part of life. It’s not something that can be wrapped up in a few panels or pages. The original audience may have delighted at the possibility of eliminating an irritating character and reveled in contributing to the direction of Batman’s life, but the creative team turned it into a showcase of the best parts of Batman as a hero: sacrificial, caring, grieved by loss and failure, tormented by his commitment not to kill and sink to the level of Joker and others like him. From a distance, this might seem like a “typical” Batman story (Batman vs. Joker, Joker gets away), but it is far from that. It’s a moving story that shows us the heart of Bruce Wayne, why he wears the cowl, and the sacrifices he makes to be a real hero. This book is not to be missed.

Think: The Life of the Mind and the Love of God, John Piper

You know a John Piper book is bad when fans of John Piper don’t think it’s very good. Such is the case with this book. At the beginning, Piper names a few other books written about how Christians are to love the Lord with their minds. Read those instead. Read J.P. Moreland’s and James Sire’s books. This is not a good book. It is written poorly, and though he does say things that are true, none of them are significant revelations necessary for the reading of this book. Do every 3 paragraphs need a new heading? No. John Piper thinks every 2-3 paragraphs need a heading. I can’t explain why. In his impatience to spout all of his repetitive comments, Piper can’t even follow his own train of thought. He says he is going to return to his 1 Corinthians passage at the end of the next chapter; two pages into the next chapter, he is back to it, saying the same thing about it he has been saying for the last three chapters. The book is quite redundant. Piper tries to do something “different” by focusing on a Biblical defense of loving God with the intellect, or at least he says that’s what this is about. It ends up being mostly a “thinking is good for Christians after all” apologetic, harping on a couple of already self-explanatory passages. He doesn’t reveal anything new on the subject, and the notion a substantial portion of genuine Christianity doesn’t think Christians should use their brains is fatuous … isn’t it? Do real Christians still doubt Jesus wasn’t telling a joke when He said “love God with your mind”? If so, as I said, read Moreland and Sire to find out why Jesus wasn’t telling a joke. If you want a better “life of the mind” book, alternatively, read Father James V. Schall’s books, especially The Life of the Mind. It’s a far more Christian book than this intellectual abysm.

—

That was fun. You’re probably wondering, “But Mr. Rush, those had almost nothing to do with your advertised summer reading goals. What happened?” Good question. We watched a lot of Magnum, P.I. this summer. Many of the books on my list are still by my bedside, waiting patiently. For some series, such as Timothy Zahn’s Star Wars trilogy and Chris Claremont’s graphic novels, I decided to read the works ahead of them, in part because of my delight in doing things in order and because I hadn’t read them yet either. I got pretty close to finishing up the first run of X-Men before Chris Claremont came along and salvaged it. I was hoping to read more New Mutants, though I spent that time doing other fun things, such as preparing for 11th Grade Bible, delighting in some Emmaus Bible College Online courses from iTunes University.

This list probably looks like I spent a lot of time reading this summer, but it doesn’t take too long to read those comics. You are probably also wondering why I read all those Batman books, since I’m a confessed bigger fan of Marvel — it’s nice to keep some mystery in our relationship after all these years, nice to know I can still surprise you. I did read a few other things, such as The Hunger Games, and I finally finished Y: The Last Man, and I made some progress on the ol’ Syntopicon and continued my “read through the Bible in a year” plan … but it really wasn’t that much of a reading summer. At least, it didn’t feel like it. Unlike many summers gone by, I didn’t spend too much time playing video games, either. So what did we do this summer? Julia and I engaged on a perpetual non-stop game of Candy Land, for one thing. We all took quite a few family walks around the neighborhood, delighted in yard saling (saleing?), grilling on the grill, and accomplishing a good deal more leisure than we got to last summer. On the whole, it was a pretty good summer. I’m not bragging; I know many of you had summers far less enjoyable, filled with strenuous work and disappointing situations (or worse) — I’ve had summers like that, too. Hang in there, kids — they won’t all be rough. Remember: God won’t leave you in the rough seasons any longer than necessary for your well being and His glory.

We hope you have enjoyed this issue of Redeeming Pandora. Only three more to go! Don’t be sad about that, though. Treasure the good times. We certainly do.

Up next: our 10th Issue Extravaganza! See you next time, Faithful Readers!