Christopher Rush

The Classic Lineup, The Classic Albums

By 1971, Genesis had secured its now-classic five-person lineup: Peter Gabriel, Tony Banks, Mike Rutherford, Phil Collins, and Steve Hackett. Over the next five years, Genesis would release five albums (four studio albums and one live album) and establish itself as the dominant progressive rock band of all time. The band mates had honed their musical talents both within the studio and in early live performances, and the arrival of more-skilled musicians (Collins and Hackett) as well as new instruments and technical recording proficiencies all allowed the band to finally create the diverse and unique sounds and songs it had desired to do since its inception.

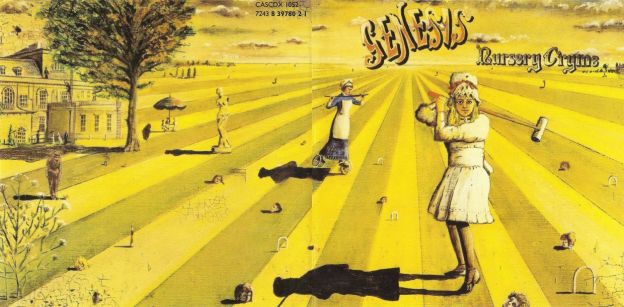

The first of the five classic lineup albums, Nursery Cryme, is still considered by some the culmination of the band’s maturation process, with its next album, Foxtrot, the real first fruits of its developmental stage. Such a view does not give Nursery Cryme its just appraisal as a quality album in its own right. Admittedly, the album does build upon the musical ideas hinted at in their earlier work, and as we found out recently with the previously unreleased demo material finally available in the box sets, many of the songs on this album had definite origins in the band’s earlier musical stages with Anthony Phillips. Even so, to consider Nursery Cryme only as another development on the way to Foxtrot as the ultimate goal misses the point of the album: it has different songs that are not trying to do what Foxtrot and later albums offer. It is a worthy and enjoyable album by itself, and it begins with one of the best (and most bizarrely creative) Genesis songs in their entire canon.

“The Musical Box”

The story behind this Victorian fairy story/epic song is included in the liner notes and depicted on the Paul Whitehead cover:

While Henry Hamilton-Smythe minor (8) was playing croquet with Cynthia Jane De Blaise-William (9), sweet-smiling Cynthia raised her mallet high and gracefully removed Henry’s head. Two weeks later, in Henry’s nursery, she discovered his treasured musical box. Eagerly she opened it and as “Old King Cole” began to play a small spirit-figure appeared. Henry had returned — but not for long, for as he stood in the room his body began aging rapidly, leaving a child’s mind inside. A lifetime’s desires surged through him. Unfortunately the attempt to persuade Cynthia Jane to fulfill his romantic desire, led his nurse to the nursery to investigate the noise. Instinctively Nanny hurled the musical box at the bearded child, destroying both.

The song takes place, fortunately, at the climactic moment of the scene described above. Henry is hovering, apparently, etherealized around or in the nursery, caught between this life and the next — similarly, he is caught between his lust for Cynthia and a bourgeoning apathy toward existence itself (“It hardly seems to matter now” repeated throughout the song). The opening strums recall us to the idyllic timbres of Trespass, but the audience has not long to wait before the maturity of the band and its aesthetic development shifts our focus away from the simplicity of the earlier album’s tonality to the wider range of sound and emotion, especially by the musical break and pounding section after “And I want / And I feel / And I know / And I touch / The wall” at the end of the opening ethereal section.

Cynthia discovers the musical box, and incorporeal Henry urges her on to open it. The story in the liner notes (and Peter Gabriel’s introduction of the song in certain live performances) indicates that Henry returns to life with his eight-year-old mind, though his body begins to age rapidly when “Old King Cole” is played. The supernatural is, as is obvious by now, a key element of Genesis’s lyrics. Briefly, Henry indicates that the good news of a future afterlife Paradise (“a kingdom beyond the skies” — very Cosette-like) is all a lie. Instead, he is “lost within this half-world,” neither fully dead nor fully alive, but he is initially unburdened by that (“It hardly seems to matter now”). The confusing aspect of the lyrics (aside from the entire supernatural events themselves) is that Henry seems to know before his resurrection that his time is short; perhaps that is why he is so insistent that he and Cynthia (despite her age) consummate their relationship — despite the fact as well that she willfully killed him with a croquet mallet two weeks before. If he knows his time is short, how does he know that, especially since his mind is still that of an eight-year-old? Despite (or perhaps because of) his prescience, Henry’s lust overpowers his ethereal apathy like the poetic contributions of Andrew Marvell and Robert Herrick: “Just a little bit / Just a little bit more time / Time left to live out my life.” The remaining time Henry has he wants to spend (in a manner of speaking) with Cynthia. She opens the box, “Old King Cole” rings out, and Henry is embodied (and embearded) and starts to age physically.

After the pounding musical interlude, the first example of the band’s musical maturity, rapidly-aged Henry confronts the apparently motionless Cynthia (her reactions and attitudes are never mentioned during the song, since it is all from Henry’s point of view). This half of the song demonstrates undoubtedly Genesis’s maturity as a band that combined provocative lyrics (admittedly sometimes abstrusely) with impressively skillful and aesthetically engaging instrumentality. Now an old man with an eight-year-old mind, Henry voices his lust for the first (and last) time. The tension and paradox of his love/lust comes out clearly: “She’s a lady, she’s got time. / Brush back your hair, and let me get to know your face.” At first respectfully and Victorianly distant, Henry quickly shifts into Marvell-mode: “She’s a lady, she is mine!” If Cynthia were a lady, even at nine-years-old, she probably would not have assassinated Henry with a croquet mallet in the first place. If she were a lady, in the second place, she would not “belong” to Henry, young or old. His lust is winning out: “Brush back your hair, and let me get to know your flesh” — an uncomfortable thought from an eight-year-old, especially toward a nine-year-old, made even more awkward by Peter Gabriel’s mask and movements during the live renditions of the song. Fortunately, Genesis is in no way condoning such an attitude or behavior, since Henry ultimately receives his just reward. We should remember, too, that Cynthia did slaughter Henry as well, and he still loves her, which makes the song thoroughly bizarre but archetypically Genesis, in the Gabriel era.

Soon Henry’s unslaked lust (as is often the case) turns into anger, though still tinged by a hint of apathy: “I’ve been waiting here for so long / And all this time has passed me by / It doesn’t seem to matter now” — apathy, or at least willingness to forgive the heretofore unrequited aspect of his lust, if only Cynthia will requite him now…which she won’t. “You stand there with your fixed expression / Casting doubt on all I have to say.” Now Henry’s anger and lust are full-boil and inseparable: “Why don’t you touch me, touch me / Why don’t you touch me, touch me, touch me / Touch me now, now, now, now, now / Now, now, now, now, now, now, now, now, now / Now, now, now, now, now, now!” They are all there — listen carefully. The nurse comes in, flings the music box at the wrinkled Henry, and both are destroyed. “The Musical Box” signals quite well the maturity of Genesis as a prog rock band with finely- (and finally-) honed lyrical and musical talent to support the epic narrative visions that launched the band five years earlier.

“For Absent Friends”

In stark contrast to the William Blake-like bizarre maturity of “The Musical Box” (though no one does William Blake-like bizarreness like early Rush), “For Absent Friends” highlights the band’s softer and sweeter side. The only thing discordant about this song is the delayed resolution at the very end, as Phil Collins’s first vocal contribution ends before the return of the dominant tonal chords provided by Hackett and Rutherford. The song has a very folksong feel to it, but the impressive part is that it does not remind one of Trespass — it is its own song while thoroughly Genesis material. Though the song is about a Sunday evening, it has all the atmosphere of a Saturday afternoon, or perhaps a Saturday late-morning, after one sleeps in with nothing much to do that day, perhaps having Welsh rabbit for lunch while still in one’s jim-jams. The song concerns an elderly couple who misses and prays for those loved ones who are no longer present in their lives, and while the song has the slow pacing to match their slow gait, it also reflects a time of youth and late-morning sunshine. Sometimes Genesis songs produce that antithetical feeling. The lyrics are straightforward, certainly among the most translucent lyrics in the band’s Gabriel-era canon, and thus need no detailed discussion here. Listen to the song with the words in front of you and enjoy a quiet, too-brief moment. Though, part of its charm is that it is so short, since if it went on longer it would spoil the mood. Sit back and enjoy the just-right song evoking both ends of life’s spectrum.

“The Return of the Giant Hogweed”

Nursery Cryme is a loosely-unified concept album in that most of the songs are nursery rhyme-like songs (the overt use of “Old King Cole” is evidence of that) dealing with children, myths, and Romance- and Victorian-atmospheric tunes; some of the songs are even loosely connected to each other. “The Musical Box” is a Victorian fairytale (of a sort), and “Giant Hogweed” is an apocalyptic vision begun by a Victorian explorer. Rooted, if you will, in the actual Heracleum mantegazzianum, the phototoxic hogweed plant that originates fairly close to where the eponymous version comes from, “Giant Hogweed” is another epic song beginning in medias res with the Giant Hogweed plants already waging their militaristic campaign.

The obvious connection is to “The Knife” from Trespass (and “The Battle of Epping Forest” in Selling England By the Pound), though “The Knife” is a lot more politically-minded and serious in tone. That may sound strange, especially since the end of “The Knife” is a tyrant’s conquering of a police force (admittedly an unfortunate thing) and the end of “Giant Hogweed” sees the end of humankind altogether, overcome by rampaging mutant personified human-killer plants.

Musically, “Giant Hogweed” demonstrates Genesis’s ability to tell a story with its musical diversity as well as its lyrical maturity. The speedy rhythms of the present scenes of the hogweed battle complement the frenetic chaos of the story. The past tense backstory verses change the musical pace well, mirroring the sounds with the words as the moods change frequently. In this diversity, the progression from “The Knife” is clear: instead of just post-production vocal manipulation, “Giant Hogweed” changes musical aspects as well as Gabriel’s vocal offerings. The band is more mature, using their instruments as contributions of the overall song and its message. Though it uses gimmicks aplenty (especially in Gabriel’s on-stage personae), the band has more to offer than simply gimmicks.

The backstory of the Victorian explorer in the Russian hills finding and transplanting the Giant Hogweed comes in agitated music-box-like verses. The melody is pleasant like a music box melody should be, but the lyrics and the pace (as if a child were cranking the music box gears too quickly) betray the simplicity of the tune with the danger of the invincible plants. The hubris of the Victorian “fashionable country gentlemen” who valued exotic botany over safety results in the gentlemen getting their due. The parallel to the destructive nature of Victorian Imperialism is there, but I wouldn’t press the connection too firmly. The effects of nineteenth-century imperialism, one could say, resulted in the world-wide destructions of World War I, but I doubt WWI is what Genesis had in mind as a parallel to the genocidal victory of the Giant Hogweed. The characterization of the Hogweed itself (or themselves) by Gabriel and the other vocal contributors is a further oddity in this lyrical story, especially in the final stanza. The line “Human bodies soon will know our anger,” were one to just read it without hearing or knowing the tune, might direct the reader to suppose Gabriel’s voice is loud and full of such anger, yet the contrary is true. The Hogweed sings this line with a music box-like mellifluousness, betraying the aggressive nature of the campaign. Instead, it is the voice of the humans in the chorus-like sections of the song that Gabriel sings with a hardened edge to his timbre. The humans exclaim, “Stamp them out / We must destroy them” and “Strike by night / They are defenseless.” Though both sides are guilty and both sides angry, Gabriel vocalizes the human race as the oppressors and the Giant Hogweed as the self-protecting and righteous combatants (“Mighty Hogweed is avenged”).

In the end, the Hogweed is victorious, but we are never told why it is the “return” of the Giant Hogweed. The Hogweed bide their time over the years, seeking to avenge their uprooting from their Russian home, but that’s not a “return”; in contrast, once the attack has begun, the humans decide they must “[w]aste no time.” The impatient reactors to the long-meditated counter-insurgency lose to the royal beast who never forgot what was done to him long ago by the Victorian explorer, and humanity pays the price. The final musical sounds utilize this call-back to earlier times, with a kind of classical- or baroque-style ending and repeated final chord — definite growth from the Trespass days only months before.

“Seven Stones”

Like “For Absent Friends,” “Seven Stones” presents a soft ballad-like break between musically harder and more driving numbers, almost to the extent the album goes back-and-forth demonstrating Genesis’s developed soft/ballad and hard/mythic narrative facets. It is possible that “Seven Stones” is the best song on the album that shows their musical and lyrical cohesion, though the time periods the lyrics and musical sounds indicate I believe are different — I am open to correction, of course. Listening to this song is very much like listening to a Victorian sea shanty about times gone by, connecting it in a roundabout way to the overall theme of the album. In contrast to the Victorian (perhaps even Edwardian) atmosphere, the lyrics are similar to a Romantic poem. The opening line, “I heard an old man tell his tale,” reminds us of the opening of Percy Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias” — in both instances, it is not the narrator’s tale that the reader proceeds to read, it is layered by the narrator recalling what he heard from another source (akin to Thomas More’s Utopia, as well). From this Romantic allusion of multi-layered narration, “Seven Stones” progresses to a parallel of Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” set within an Irish heather or Scottish highland “seventh son, seventh stone” magical fairy-tale background.

The first tale the old man tells is of a “Tinker, alone within a storm,” who is “losing hope” and “clears the leaves beneath a tree” under which he discovers the eponymous seven stones. We are not told if the tinker takes these stones with him or if he leaves them, only that he later finds a friend in the seventh house he seeks out: apparently the stones (either magically or placebo-like) gave him hope to press on and his friend relieves him from the dangers of the storm — he was not as alone as he thought he was. The shift from this story to the next is the most ambiguous line in the entire album: “And the changes of no consequence will pick up the reigns from nowhere” — superior to the ambiguous lines from the From Genesis to Revelation days, this line is a Coleridgean/Blakean bizarreness that seems to fit quite well. The tinker’s change from hopeless isolation to befriended succor is certainly not of “no consequence,” so what the inconsequential changes are we are not told (perhaps because of their very inconsequential nature) — but then they take up the reigns from nowhere, as if what we thought were inconsequential then become the most consequential because they are now in control (holding the reigns — perhaps of destiny or Nature itself, perhaps by the power of the seven stones themselves).

The second story is the definite “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” parallel: sailors are imperiled on the sea about to strike a rock (though this did not happen in Coleridge’s poem) until a gull flies by and the Captain is moved by an unknown force to change course (similar to the supernatural effect the albatross and its slaying has in Coleridge’s poem, but it is admittedly distinct and thus a parallel, not an exact copy). Whatever the inconsequential changes are in this story, they likewise take the reins from nowhere.

At this point, the old man takes a break (as evidenced both by the lyrics and the vocal change in Gabriel’s sound) and we learn some surprising things about this old narrator and his ambiguously supernatural tales from yet another narrator layer, this time an angelic-like omniscient chorus: “Despair that tires the world brings the old man laughter, / The laughter of the world only grieves him, believe him, / The old man’s guide is chance.” It is difficult to accept why we should believe the stories of someone so contrary to the fabric of reality, who laughs at what brings most of us despair, who grieves at what brings most of us happiness and relief, and who is ultimately guided not by an absolute standard of morality or destiny but by that most fickle of masters: chance. Perhaps, though, that is the point. The things that we laugh at are truly trivial and inconsequential. The things that we are afraid of should be what we laugh about (the seriousness of human affairs, for example?). If chance is the reliable guide, does chance have a connection to the seven stones and the natural/supernatural influence of the gull? If the old man believes in chance and human action and not divine structure, perhaps the stones had no intrinsic power after all, and superstition alone led the tinker to safety; similarly, the Captain who turned his boat to safety, instead of rationally asking why the gull was there, intuitively changed course because of chance.

The old man’s third tale (or second, if the tinker and sailors are two parts of the first tale) features the old man himself and gives further support for his Romantic philosophy couched in a Victorian/Edwardian song. A farmer, who is apparently a very bad farmer, since he “knows not when to sow,” which is an essential skill for farming, approaches the old man for assistance rather desperately, since he is “clutching money in his hand.” The old man shrugs, smiles, takes the money, and leaves “the farmer wild.” Not much (if anything) should be read into the fact the old man with a Romantic/cavalier attitude steals money from a farmer, a man who works closely with the land and thus nature, which a Romantic should value — especially since the farmer is not very good at knowing the land. With the old man’s thievery, the changes of no consequence pick up the reigns from nowhere, and soon the song comes to a close. Nothing more is learned about the old man, the ethereal chorus, or the original narrator who is listening to the old man’s tales.

“Harold the Barrel”

Another Phil Collins cymbal roll heralds (I apologize) the shift from the “slow, melodic Genesis” to the “quirky, eclectic sounds and stories Genesis.” “Harold the Barrel” is certainly one of their quirkier songs in the Gabriel era. The song is a send-up of inane news reporting about topics of “local interest,” which, if relevant in 1971 England, is certainly relevant to today’s even crazier “news”-saturated, media-driven culture. Like with most “news” stories, the veracity of the content is questionable at best. Genesis does a trenchant job of clouding the issues, obscuring the perspectives, and rejecting any satisfactory conclusion to the episode.

Harold’s “mouse-brown overcoat” tells us that he is himself mousy, and thus weak and ineffective. The next tidbit we learn is he is a father of three and has done something disgusting, apparently cutting off his own toes and serving “them all for tea,” though we are not told if they are served to his sons or if the entire thing is just community gossip, since Harold is a “well-known Bognor restaurant owner,” which means no one knows him at all. The community soon revolts against him, and the train he took early this morning to escape will not take him far. That Harold “hasn’t got a leg to stand on” is a remarkable line of Gabriel’s developed dark humor and lyrical skill: not only has Harold supposedly cut off his toes, he has no leg, either.

Before too long we infer that the information of Harold catching a train to escape early that morning is not true (either that he didn’t take a train at all, or just that he took a train not to escape but to get to the town hall where Harold is actually standing out on a ledge, perhaps ready to jump and end it all in a “Richard Cory”-like fashion except jumping from a ledge, not shooting himself with a gun, of course). The reporter on the scene describes the gathering crowd at the town hall as “a restless crowd of angry people” — so restless that the city council has “to tighten up security.” Why are they so angry? Are the rumors about his teatime snack accurate? It is never mentioned again, nor does the rest of the song give any tacit credence to such a tale. Genesis could be ridiculing not only the nature of news reporting but also the mob mentality of onlookers — with no facts to ground their emotions upon, anger becomes the easiest communal response.

Even the Lord Mayor gives no leniency to Harold: “Man of suspicion,” he calls Harold, “you can’t last long, / when the British Public is on our side.” What are the sides? What is the issue? Poor Harold is standing on a ledge, obviously discontent over something, and not only is the mindless citizenry against him for no apparent (or rational) reason, but also the elected officials are against him. Mob mentality is king, here, since the Mayor himself appeals to general consensus: if the Public believes this ledge-hanger is guilty of something despicable, he must be, regardless of who he is, what he has done, or why he is even there. Their communal antipathy increases in appetite, as they chant menacingly that “he can’t last long” (they clearly don’t want him to) and that supposedly this mindless mass earlier indicated that Harold couldn’t be trusted, “his brother was just the same.” Why bring his brother into this? Of course no one earlier voiced any concern about Harold; certainly we should place no credence in their filial associative gossip.

The sweetest moment of the song is the brief interlude from Harold’s perspective, as he looks out over the enraged citizenry and imagines where he would like to be instead: “If I was many miles from here, / I’d be sailing in an open boat on the sea / Instead I’m on this window ledge, / With the whole world below.” The music accompanying this brief reverie is very enjoyable, especially as it is a break from the frantic cymbal-splashing highlights of the mob mentality and gossip-laced reporting.

Another shift occurs as the mob takes on a patina of Good Samaritan behavior: Mr. Plod (most likely the Lord Mayor, no doubt a pertinent name for his character and approach to his work and life in general) tells Harold “We can help you,” which the drones in the crowd repeat. “We’re all your friends / if you come on down and talk to us son,” he continues. Harold and we know this is a hollow lie. “You must be joking,” is Harold’s appropriate and impassioned response. “Take a running jump!”

The Samaritan shift in attitude seems to increase, as the crowd, once glad that Harold was out there ready to jump, is now concerned that he is getting weaker, so much so that they send for his mother, which does not help at all (it is difficult to ascertain if the crowd brings in his mother to further his decision to jump or not, since it is highly doubtful they knew anything accurate about the family anyway). Were it not for the fact Harold’s mother is called Mrs. Barrel, the title calling Harold “the” Barrel might indicate that he is nothing more than a receptacle for other’s emotions, plans, and manipulations (this still may be the case, since, even if Harold’s last name is actually Barrel, the title calling him “the” Barrel may just highlight his prior nature up to the point he steps on to the ledge). Mrs. Barrel gives Harold very poor reasons to come back inside: if his father were alive, he’d be upset with Harold’s actions; and his shirt is all dirty and thus he is embarrassing her, especially since a man from the BBC is there to capture his disgraceful appearance on film. Meanwhile, the crowd resorts to content-less social acceptability: “just can’t jump” they say over and over. Why not? Because it’s not what people do, apparently. No one is concerned for Harold, no one bothers to inquire why he is there at all. Mr. Plod and his chorus repeat their earlier pleas to Harold that since they are friends, he should just come down and talk to them, which Harold rejects as before. And suddenly, the song is over. The music does not tell us if Harold jumped or returned inside. Like all “news” stories of today, the result is irrelevant. The connection to our lives and why it should matter to us is ignored completely. The motivation behind Harold’s actions is never sought. The song ends; the “news” cycle continues on to something else.

“Harlequin”

I have posited that Nursery Cryme is a loose concept album, primarily in the moods of the diverse songs generated, as well as the (admittedly thin at times) lyrical connection to nursery tales of myths, magic, and medieval wonderments. “Harlequin” furthers the tonal mood aspect of the album, especially since Gabriel’s vocal work on this song is dominantly falsetto. This song feels like a Harlequin is singing it; it also evokes a pinwheel being blown by the breeze — this song is a pinwheel, and all the simplicity of youth and pre-Econ class joy we once had. (Not that Economics class is bad, just that it usually occurs at the end of our high school days when we are about to fully embark upon maturity and college, and the days of playing in the dirt with action figures and pinwheels are mostly lost to us.) Little needs to be said here about this song; it is too lovely to dissect. In closing, though, it is a very hopeful song, as clearly indicated by the final chorus. The words and music paint a very enjoyable (and again almost unfortunately brief) aural painting.

“The Fountain of Salmacis”

A final Collins cymbal roll brings the final song of this Wonder Book-like collection of tales and fancies. The story of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis is even older than Ovid, but his version in Metamorphoses is probably the best known. The liner notes recap the story for those less literate consumers of prog rock:

Hermaphrodite: a flower containing both male and female organs; a person or animal of both sexes. The child Hermaphroditus was the son of Hermes and Aphrodite, the result of a secret love affair. For this reason he was entrusted to the nymphs of the isolated Mount Ida, who allowed him to grow up as a wild creature of the woods. After his encounter with the water-nymph Salmacis, he laid a curse upon the water. According to fable, all persons who bathed in the water became hermaphrodites.

Little needs to be said as well about the lyrical content, since it is mostly a straight re-telling of the story, without the complex narrative layering of “Seven Stones” or limited narrative focus of “The Musical Box.” This song, though, fits well with them and completes this diverse but connected album. The variations in musical texture at various narrative points in the song are reminiscent of and superior to similar attempts from Trespass, and as has been said so often about this album, the music helps tell the story very well. The most interesting (and unique) aspect of this song could also be its most frustrating for some: at the end of most verses, either Salmacis or Hermaphroditus says something cogent about her or his feelings or reactions in first person, and usually the omniscient narrator of the song makes a similar comment in third person — at the same time. This overlapping of words/perspectives is challenging to comprehend the first time or two through the song (especially if one listens without the words in front of him), but it is a unique element that adds to the fast-paced confusion and immediacy of the events in the confrontation of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus. After setting the blissful scene at the beginning of the song, the rapid action of Salmacis waking up, falling for Hermaphroditus, and their conjunction (against Hermaphroditus’ will) needs a confused, perplexing cacophony to express the moment accurately — and this overlapping of narrative presentation succeeds in that unusual task (concerning such unusual characters). As an aside, Hermaphroditus’ line, “Away from me cold-blooded woman / Your thirst is not mine” is a sharp indicator of Gabriel’s mature lyricism, combining the emotion of a moment with the irony of the situation, as Hermaphroditus was there to slake his physical thirst for water, but the waken Salmacis has a different kind of thirst when seeing Hermaphroditus.

With Hermaphroditus’ curse, the music winds down to its initial calmness, as the two (and a half) beings descend to their eternal condition: “Both had given everything they had. / A lover’s dream had been fulfilled at last, / Forever still beneath the lake.” The musical conclusion is similar to the ends of other songs on this album, though the sounds are in line with the tenor of this particular song and the somber mood at the end of the lyrics. In another sense, the final musical exchange fits with the album as a whole in that the diverse presentation of tones, stories, and emotional energies climaxes with the lovers’ (after a fashion) embrace and resolution — everyone is worn out and almost resigned by the end, including the musicians. It is time for peace. The album is a triumph, both for Genesis and for the progression of music itself, but the impressive creativity and emotional energy from everyone has been exhausted, and so it is not so much a victory that is being celebrated (not even for Salmacis) as it is a cathartic completion with the understanding that now even more will be expected and even more must be done (similar to John Adams’s “It’s done! … It’s done,” at the end of 1776).

“Some Creature Has Been Stirred”

I have said throughout that those who see Nursery Cryme as the last of the developmental albums before the heyday of Genesis’s Gabriel era are missing the point. That is not to say that with this album Genesis peaks and remains static for the next four albums or so, nor is it an implication that the Collins era (or even the short-lived Ray Wilson era) is ultimately inferior — they are all different entities, with different emphases and different highlights (and lowlights). I suspect that most who argue for Foxtrot’s superiority to Nursery Cryme base their argument solely on personal enjoyment: they like listening to Foxtrot more, probably because of “Watcher of the Skies” and “Supper’s Ready.” I have already admitted that I enjoy Foxtrot more than I enjoy Nursery Cryme, but that is not because I think it is a better album — they are similar, yes, in several ways obvious to even a cursory appraisal, but they are different albums, and the band members display their lyrical and musical skill extremely well on both. Let us not let the mighty penumbra of “Supper’s Ready” take away from our appreciation and enjoyment of “The Musical Box” and “The Fountain of Salmacis.” Neither should we let the perfection of “Horizons” diminish our capacity to revel in “For Absent Friends” and “Harlequin.” Nursery Cryme is the beginning of the great golden age of Genesis in the Peter Gabriel era, and it should be listened to and enjoyed because of its own merit.