Christopher Rush

Introduction

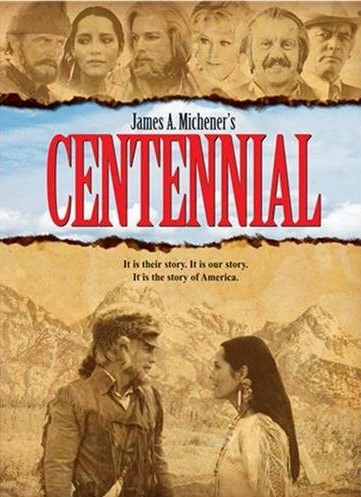

The mini-series (perhaps more accurately “maxi-series”) reached its perfection with 1978-79’s mighty Centennial, the 12-part adaptation of James A. Michener’s novel of the same name. Not as long as War and Remembrance, not as culturally shattering as Shōgun or Roots, Centennial is nonetheless everything that television mini-series adaptations/original stories could be. This is its story.

Only the Rocks Live Forever

The mini-series opens with a panoramic shot of the mighty landscape of Colorado, and James Michener himself steps forward to introduce the story: in essence, the story of Centennial is a story of the land and its inhabitants – perhaps more the land itself, though its inhabitants are an integral and changing aspect of how the story is constructed. The Platte River, the farmland, the open plains; trappers, settlers, farmers, cowboys, shepherds — the land and its people create this story of America. Under Michener’s direction, the mini-series contracts the first three chapters on the formation of the land and the evolutionary progress of the animals into a brief visual effect and David Jannsen voiceover. What will become northern Colorado is populated by the Arapaho, including a young boy named Lame Beaver (played, eventually, by the powerful Michael Ansara), who, raised by his uncle, learns, among other key lessons, that human life is frail and temporary: only the rocks live forever. Lame Beaver makes a name for himself by stealing horses from a rival tribe and bringing them to the Arapaho for the first time. With the new form of transportation, the Arapaho lifestyle is changed forever, as they join the plains horse culture. Soon Lame Beaver and the audience are immersed in the pelt-trapping days of the mid-18th century through the French Canadian fur trapper/trader Pasquinel.

Pasquinel (played by Robert Conrad with what always appeared to me to be a believable French-Canadian accent — some may disagree, but that is their right as citizens of the world) is the main character of parts one and two of Centennial — though a trapper and trader, Pasquinel knows the land, the rivers, and the animals, which makes him in one sense the ideal inhabitant according to the novel. Pasquinel embodies the simplicity of living off the land, not taking too much simply for profit but utilizing the cycles of life without disrupting the balance of nature (unless you count selling guns to various tribes), but he is no thoughtless tree hugger. He sells guns to competing tribes to gain access to more pelts and safe travel. After being wounded by the Pawnee, Pasquinel is robbed and assaulted by river pirates who take his pelts after months of work. Returning to St. Louis (“San Looiee”), Pasquinel is forced to partner with Bavarian silversmith Herman Bockweiss (Raymond Burr without a wheelchair) as his financial backer. With the Pawnee arrow permanently stuck in his back, Pasquinel furthers his ties to St. Louis by marrying Bockweiss’s daughter Lise (Sally Kellerman) — he does love her, in as limited a fashion as he is capable of, but he never hides the fact he is mostly interested in financial support for his fur trading life.

Back in the field, Pasquinel meets the naïve yet thoroughly honest (and, frankly, totally awesome) young Scotchman Alexander McKeag (the one and only Richard Chamberlain, king of the mini-series). Rescuing him from his own nemeses the Pawnee, Pasquinel trains McKeag in the ways of the American fur trade, and they become life-long friends … of a sort. Like all epic heroes, McKeag is soon wounded rather drastically, primarily because he doesn’t listen to Pasquinel during an Indian coup. Pasquinel saves McKeag’s life and helps him regain his confidence, just in time for the major schism in their friendship to occur: her name is Clay Basket (Barbara Carrera); she is Lame Beaver’s daughter.

Clay Basket falls for shy, gentle McKeag, naturally; Lame Beaver, however, demands that she marry Pasquinel, ensuring both her financial security and the continual supply of guns to the Arapaho. Lame Beaver settles his plans for his family before ending his life-long feud with the Pawnee — but not before he discovers gold in a nearby riverbed, though he doesn’t know its future significance; to him, it is a shiny malleable metal useful for making bullets to kill his enemy. When McKeag and Pasquinel return the following season, Pasquinel marries Clay Basket and learns about the gold, believing she would know where her father found the gold. McKeag, knowing his friend does not love her, recognizes the motivation behind Pasquinel’s actions, and their friendship starts to fray.

The Yellow Apron

Years pass and Clay Basket gives birth to Jacques and Marcel. Pasquinel continues to spend time both in the field with McKeag and his Arapaho family as well as time in St. Louis with Lise. McKeag does not approve, of course, but remains loyal as long as he can, in part because he cannot part from Clay Basket. Jacques senses the tension, though he does not understand it. Pasquinel, upon his return, foolishly determines to take his family to St. Louis; at an army fort, drunken soldiers deride Pasquinel and his half-breed family, resulting in a serious wounding of Jacques, who never forgives the White Man for what happens to him; later, Jacques is also wounded by a Native arrow, cementing his (and his brother’s) isolation from both worlds. Pasquinel spends time with Lise, letting her know about his Arapaho family (though, being a wife, she had suspected so for a long time, just as Clay Basket does); McKeag tries to teach Jacques and Marcel how to trap in the meantime, though Jacques soon grows tired of his substitute father. Eventually Jacques takes his frustration out on McKeag, stabbing him nearly to death. McKeag retaliates briefly but he restrains himself; after all, Jacques is Clay Basket’s son, but he is also “twisted” with rage, and McKeag knows he can no longer stay.

Though Pasquinel salvages a temporarily successful family life with Clay Basket and the boys (and his future daughter), he soon becomes obsessed with discovering Lame Beaver’s gold strike. Meanwhile, McKeag becomes an isolated mountain man, trapping alone and almost going mad from the lack of community. Eventually he learns of a Rendezvous of mountain men (one of the many historically accurate events Michener includes throughout his grand saga) and decides to go, if only to see his former friend (and Clay Basket) again.

At the Rendezvous, McKeag releases some pent-up frustration, even wearing the Yellow Apron to show off a classic Highland dance — during which he reunites with Pasquinel, and they are able to set aside their differences and enjoy some time together as old friends. One of the key traits of Centennial is that noble, generous people often have both a second chance at love and the time to amend past wrongs — not everyone does, but most of the “heroes” of the tale do, primarily because of their goodness. By this time, Jacques (Jake) and Marcel (Mike) have grown up to be angry young men, though Jacques is far angrier than Marcel. Jacques can shoot better than most white men, even with their muskets. The reunion is short-lived, however, as the old arrow wound acts up and causes Pasquinel to pass out. At Pasquinel’s request, McKeag cuts out the arrowhead, giving it to Jacques as a souvenir. Pasquinel asks McKeag to join them, at least to see Clay Basket again (who is away, tending their young daughter Lucinda), but McKeag refuses.

Years later, McKeag makes his way to St. Louis and meets Lise and her daughter Lisette, telling Lise the truth about Pasquinel and his life. Lise in turn convinces McKeag to follow his heart after all these years and confront Pasquinel and try to win Clay Basket for himself (though not out of selfishness to have her husband all to herself — it is too late for that). McKeag does so, in part because Jacques and Marcel are no longer with their parents. Pasquinel finally finds Lame Beaver’s gold, only to be mortally wounded by Arapaho warriors. McKeag and Clay Basket come upon him in his final moments, and Pasquinel entrusts her to McKeag, knowing he will take far better care of her than he ever did. Not knowing the gold is around them, McKeag leads Clay Basket and Lucinda away to a new life.

The Wagon and the Elephant

Part three sends the story in a new direction while (like Les Misérables) also rejoining the original storyline already in motion. Parts 1-5 are a loosely unified story about Native Americans and other early inhabitants of the land (trappers, mountain men, and prospectors); parts 3-8 are also the extended story of Levi Zendt, a Mennonite runaway, and his industriousness helping turn the land from its rugged, natural beginnings to a bastion of civilization (with other sub-stories about the land and its inhabitants along the way). Parts 9-11 resolve some of the other storylines already developed midway through the series, bringing the land into the 20th century. Part 12 takes place a couple generations later, acting more as a dénouement than a direct resolution, eventually leading to the tale of Centennial being told., bringing the series full-circle (in a Roots-like way).

Levi Zendt (Gregory Harrison) is a young, hardworking, honest Mennonite growing up in Pennsylvania in the middle of the 19th century. Despite the strenuous and strict lifestyle, Levi finds himself interested in young Rebecca who, unbeknownst to him, is also sought after by his elder brother. Rebecca knows this, and being one of those girls, coquettes Levi in front of the orphanage, then, as girls of that ilk tend to do, shifts the blame upon Levi, whose reputation is ruined. He is formally shunned by his family, except his intelligent mother who gives him money and the family horses, telling him to leave and start a new (real) life for himself. He begins his new life by buying the eponymous wagon and then picking up Elly Zahm (Stephanie Zimbalist at the precipice of her Remington Steele fame), his friend at the orphanage who knew Rebecca was making up the story. Together, they embark for the west, totally unprepared yet vital and enthusiastic. Their first stop (after getting married) is St. Louis. There, they join a group following the Oregon Trail with young and authoritative Captain Maxwell Mercy (Chad Everett) and his wife Lisette Pasquinel Mercy. Also on the trip is naïve English author Oliver Seccombe (Timothy Dalton before his hardened James Bond days) trying to prove Native Americans derived from Welshmen. This ragtag group is led by the thoroughly repugnant (both physically and morally) mountain man Sam Purchase (Donald Pleasance in one of his least pleasant roles, which is saying quite a bit for his storied career). Without Levi’s knowledge, Purchase sells Levi’s family horses for cattle, ending Levi’s last tie with his old life (he’s sort of a mix of Marius and Aeneas, really). Captain Mercy is on deployment to a frontier army fort (at which McKeag and his family live) in part to set up connections with the western tribes, hoping his wife can make emotional ties to Jake and Mike Pasquinel, now grown up terrors on the plains, since she is their half-sister (to the extreme).

After meeting McKeag, Clay Basket, and now-grown Lucinda, Levi and Elly continue west without the safety of Captain Mercy. Soon into the trip, Purchase tries to rape Elly, though Seccombe and Levi prevent it (and then Seccombe prevents Levi from killing Purchas). For Levi and Elly, this is the last straw, the eponymous “elephant” (something so big and devastating that it destroys all hopes for the future and ends their plans in failure). Upon their forlorn return east, they team up with McKeag and his family to start a new settlement and trading post away from the army fort and closer to Clay Basket’s Arapaho home grounds, in part because Elly is now pregnant and she doesn’t want to head too far in their old wagon in her condition. Before they can begin this new phase of their life, Elly is bitten by a rattlesnake and dies instantly. Devastated, Levi leaves the McKeags and their trading post for McKeag’s old mountain man isolated fort, mourning for Elly and their unborn child.

For as Long as the Waters Flow and The Massacre

After what may or may not be an appropriate mourning period, Lucinda McKeag goes to console Levi in his isolation and grief. Furthering Centennial’s trope of second-chances for love, Levi and Lucinda begin their romantic relationship shortly thereafter. As that begins, the story adds another element: Hans Brumbaugh (Alex Karras) and his farming. Brumbaugh does not begin as a farmer; in fact, he begins as a prospector who runs into Spade Larkin, another prospector looking for Lame Beaver’s gold. Larkin pesters Lucinda too much about the gold, believing she would know where her grandfather’s gold came from, but she obviously doesn’t. Without her help, Larkin and Brumbaugh find the vein but have an altercation resulting in Larkin’s death. Brumbaugh feels guilty about Larkin’s accidental death, leaving the gold behind for a new life as a potato farmer, buying land from Clay Basket.

The major focus of parts four and five is the conclusion of the “Indian Problem.” McKeag’s role in the story comes to a conclusion during Levi and Lucinda’s wedding. Though she has spent time back in St. Louis developing her literacy (and fending off the romantic pursuit of young Mark Harmon), Lucinda has committed her heart to Levi. Jake and Mike, taking a break from harassing settlers and farmers (though they believe they are defending their territory from interlopers, and they are probably right), come to see their mother and sister again. Jake and McKeag even lay aside their life-long grudge for the sake of Lucinda’s happiness and the potential reconciliation of Indian and white settler. During a revisit of the Highland reel that helped reunite him with Pasquinel, McKeag has a heart attack and dies in Clay Basket’s arms. With him dies as well any real chance of formal unity between the Indian tribes and the westward-moving American settlers/army. Major Mercy returns as well to further the negotiations. Jake and Mike are willing to listen to him, knowing his integrity, and eventually some treaties are signed, granting the Arapaho and other nations certain lands “for as long as the waters flow.” Levi, having taken over McKeag’s trading post and role as peacemaker, can only do so much to stem the tide of governmental deception concerning the Indian nations. We all know that despite Mercy’s integrity and willingness to ensure his promises, it is only delaying the inevitable expansion of post-colonial America. The burgeoning Civil War also marks the end of peaceful cooperation with the Indians.

“The Massacre” is probably the saddest episode of the entire series, bringing to a close all the major storylines and characters that began this saga as well as showing, in a remarkable degree of honesty, the lack of integrity and humanness of 19th-century American governmental and military policy and action. Centennial really has only two major villains: Frank Skimmerhorn here in part five and Mervin Wendell in parts nine through eleven (three, if you count Wendell’s wife Maude), but Skimmerhorn (played frighteningly well by otherwise-nice guy Richard Crenna) is clearly the worst character in the entire saga. With the army presence on the frontier decreased due to the Civil War back east, the Pasquinel brothers have been causing a great deal of disturbance. Playing upon settlers’ excited passions, Skimmerhorn (who already has a preternatural hatred for all-things Indian based on things he experienced back in Minnesota) gathers a militia with official army support and leads a raid on the remnants of the Arapaho people, who by now have no weapons, no warriors, and virtually no horses. Mark Harmon’s character, Captain McIntosh, returns as a member of Skimmerhorn’s army, though he refuses to join in on the massacre and is temporarily discharged. The arrant perniciousness of Skimmerhorn is exemplified in his line “nits turn into lice,” when referring to two Arapaho infants being held by one of his acolytes. The “soldier” assassinates the two infants, revolting young Private Clark who joins Captain McIntosh’s dissenters. The massacre becomes public knowledge but as a victory against Indian aggression. During McIntosh’s court martial, adjudicated by General Asher (Pernell Roberts sans stethoscope) who had earlier assisted Mercy’s negotiations with the tribes, Private Clark’s testimony about Skimmerhorn’s actions and comment about the baby Arapaho sway public sentiment against Skimmerhorn, and McIntosh is restored to honor (though he has, of course, forever lost Lucinda to Levi). Despite the temporary backlash, Skimmerhorn rebounds back into popularity enough to gather a militia to lynch the Pasquinel brothers. Stephen McHattie’s performance as Jacques (Jake) has been sterling for several episodes, but his performance at the end under Skimmerhorn’s abuse is stellar. Once they learn of Jake’s death, Levi and Lucinda convince world-weary Mike to turn himself in to the “real authorities,” since only then can he get a “fair trial.” He never gets one. On the way to turning himself in, Mike is shot in the back by Skimmerhorn. Mercy is so enraged by Skimmerhorn’s actions that he challenges him to a duel, willing to abandon his military career to end Skimmerhorn (even though it is essentially too late). Skimmerhorn’s son John arrives in time to see Mercy beat him nearly to death — though Levi prevents him; sickened by his father’s behavior, John rejects him outright. Skimmerhorn is banished from Colorado, the damage already done. The Civil War ends, the army returns, the Indians are gone, and so are all the original characters and storylines from the beginning of the saga. It is time for a new focus.

The Longhorns and The Shepherds

The new focus comes dramatically and starkly with episode six, “The Longhorns.” Only a couple of the new stars of the series make brief appearances, and the focus shifts to the new diverse inhabitants of the land: this time, the cattlemen. Oliver Seccombe returns, having failed as a writer, now giving cattle baron a try on behalf of the Earl Venneford estates of England. Utilizing the Homestead Act in a rather shady way, Seccombe and the Venneford Ranch eventually overtake over six million acres — in part by claiming the right of contiguity: their cattle can also roam on land contiguous to their own. Though Seccombe is still trying to be an amiable and honest business man, the pressures of his role and his own lack of experience in cattle ranching eventually overcome his integrity, though not for some time.

Hans Brumbaugh is one of the main opponents of the Venneford, but his antipathy is only touched on here in a brief confrontation with Seccombe. The majority of the episode is turned over to a new set of characters led by Dennis Weaver as R.J. Poteet. John Skimmerhorn returns to live down his father’s shame by doing good for the community by assisting Seccombe with a cattle drive from Texas up to Colorado, where the location of the series takes place, in what is now called Zendt’s Farm in the Colorado Territory. Skimmherhorn gets the assistance of Poteet, the best trail boss in the business, as well as the typical rag-tag group of experienced cattlemen who know all the old jokes; the typical youngster who needs to settle a family debt and become a man, Jim Lloyd (soon played by William Atherton much less smarmy than he is in Die Hard one and two); and even the typical Mexican cook Nacho. The drive features all the stock Western cattle-drive movie elements: Indian skirmishes, lack of water, internal conflict with the loner, Jim’s struggles coming of age on the drive, losing a few guys we’ve come to love from injury and sickness, and the eventual success of the trip. Along the way are the occasional Natty Bumppo-like messages about the greatness and grandeur of the natural world, the open range, and how these days are never going to come again, due, ironically enough, because of the very things the cowboys are doing: establishing mega-ranches and centralized townships of power along the frontier, turning it from an untamed, natural wilderness into civilization itself — an irony the Poteet himself wistfully realizes and laments. Though the episode has all the attributes of a stereotypical treatment of the “ol’ West,” it escapes the syrupy-sweetness of what it could have been and is rather an enjoyable episode, despite having almost no connection to the episodes and characters (and scenery) that have come before. The characters, though typical, are real and engaging, the conflicts, though typical, are likewise believable, tense, and entertaining. The message of the episode, as so often occurs throughout Centennial, is present without being heavy-handed, and we end up believing the cowboys and, despite the hardships, miss the days and freedom of the open range.

The ever-changing nature of the passage of time and life is furthered by the next episode, “The Shepherds,” which acts in part as a dénouement to “The Longhorns” as well as another transition to the next few episodes, as the saga of the land and its inhabitants takes on new guises and new conflicts. Though it is called “The Shepherds,” it is more about the conflict of the land’s new inhabitants: homesteaders, farmers, shepherds, and cattlemen. The land can only sustain so much, and the arrival of Messmore Garrett and his sheep is the last straw. As Seccombe and secret agents of the Venneford start gobbling up farm land, Seccombe’s financiers force him to descend into hiring gunmen to drive off homesteaders and shepherds, despite the fact some of the men attacked and killed are former cowboys he hired to bring the cattle to the Venneford in the first place years ago. Time passes rather quickly between episodes, sometimes confusingly so, but the theme of time passing does not affect our emotional attachment to the new characters, especially as they sometimes meet tragic ends at the hands of other characters we care about. Adding an extra layer to Seccombe’s character is his romance to Charlotte Buckland (Lynn Redgrave), daughter of one of his visiting financiers. Their romance continues Centennial’s theme of second chances for love, but we also have the sense that Seccombe is becoming a cattle baron version of Macbeth, despite his growing amour.

The uncontrollable passage of time is shown clearly in this episode during David Jannsen’s voiceover: Zendt’s Farm is now called Centennial, and the Colorado Territories is now a state in the union (called Colorado). The Arapaho, like most Indian tribes, have been removed to reservations (in a great symbolic scene). The lawless frontier days are no more, and this new structure and civilization is embodied in husky Sheriff Axel Dumire (Brian Keith in a role that won’t surprise you). The range war is his major target, and though it reaches an unusual end with a unique amalgamation of the warring factions for a matter of vengeance, Dumire closes the episode by scolding the various warring parties: this battle is over, and time moves on; if one wants to live in a civilized town, one has to comport oneself in a civilized way. It’s time to bury the dead and let life move on.

The Storm and The Crime

At this point of the series, the character role call has grown rather large, and it is time for both flashbacks of key events and a bit of a clearing out. Calling “The Storm” another “Longhorns” dénouement would be partly correct, in that we see more of the Poteet cattle drive characters make a brief (and tragic) return, but the episode serves more as a continued transition to the character conflicts of the final episodes. The timing of this episode is a bit confusing, in that Levi is visiting his Pennsylvania kinsman for the first time in decades, and that trip supposedly only takes a few weeks, but back in Centennial it appears a few months (or more) have passed (the spring of “The Shepherds” has been replaced by an early winter). The recent theme of the inevitable passage of time is set in stark contrast to the unchanging (stagnation?) of Mennonite Pennsylvania. Levi is able to finally reconcile with his family and tell Elly’s old friend about her death, but the entire trip is unsatisfactory for him — this is not his home; his home is in Centennial with Lucinda.

Oliver Seccombe’s financial troubles escalate throughout this episode, despite the efforts of Charlotte to encourage him and help him see his good qualities. Though we completely believe Oliver’s love for the land and his sacrificial tactics to provide for Charlotte, we also know he has engaged in dubious practices to maintain the patina of prosperity for the Venneford backers in England. The arrival of accountant Finlay Perkin (Clive Revill) furthers Seccombe’s concern, since British accountancy does not align with American-range bookkeeping. The eponymous storm by the end of the episode destroys the crops, the cattle, and Oliver’s hopes.

Though the episode begins with some of the funnier moments in the series (especially in the later group of episodes), it does not end very humorously. In addition to the destruction of Seccombe’s hopes and dreams, the storm brings the end of one major story and the beginning of the last story: after his return from his Pennsylvania visit, Levi makes some weighty and impressive (though theme-heavy) comments about man as an individual and his responsibility in the face of Time and History … only to be killed shortly thereafter in a railway accident, filmed in a heartbreakingly perfect way, for all of the irony involved. Lucinda is still around for awhile, true, but the death of Levi really concludes all ties to the characters and struggles from the beginning of the saga: and appropriately enough, the episode ends with a brief flashback tribute to the characters that had come before, characters who cared more about the land than the people who inhabit it now seem to do.

The last character arc/story begun at the end of “The Storm” is further developed in “The Crime,” and that is the story of the Wendells, travelling actors (con artists more like) that have prior acquaintanceship with Sheriff Dumire. Though they are struggling actors trying to be honest and make a living at first (or so it appears), their shady past catches up to them and Dumire impounds their earnings, leaving them penniless and homeless — until the gullible preacher comes by, rescues them, and soon falls for Maude Wendell, allowing them to pull the ol’ “badger game” on him, blackmailing him out of a home and steady income. Soon the Wendells get cocky and careless and the badger game backfires, resulting in the death of a businessman by Maude — their son Philip, witness to the whole event, hides the body in an underground cave in the same area that houses Lame Beaver’s gold strike, though he doesn’t notice. The Wendells take the businessman’s wealth, but they realize he can’t spend it for that would arouse Dumire’s suspicions.

The last of the old characters ends his story in “The Crime” as well, as Oliver Seccombe, saddened by the loss of the land more than the loss of his cattle empire, commits suicide on the range, leaving Charlotte alone. She soon returns to England. The Indians are gone. The fur traders and mountain men are gone. The pioneers are now industrialists and businessmen. Nothing’s the same anymore.

The Winds of Fortune and The Winds of Death

With very little connection to the beginning of this saga, some might find these final episodes dull and irrelevant, but that would be a great disservice to what Michener’s entire purpose is: reminding us that time passes, things change, but the land remains, and we need to be wise stewards of it.

Charlotte returns from her England trip and soon falls for the older Jim Lloyd, though their romance, like all romances in this saga, goes through its initial hiccoughs. By now Jim is essentially the last of the old cattle drive people; the shepherds have had their way, the cattle are almost no more, and even Brumbaugh and his new beet empire reach their zenith as he, too, has to adapt to new ways of living. Homesteaders are likewise a thing of the past and the civilized land Dumire helped to establish is quickly becoming the modern world of the twentieth century.

The Wendells’ conflict with Dumire reaches an interesting plateau, as young Philip has to balance his admiration for the strong, noble lawman with his commitment and filial obligations to his shady parents. Dumire never gives up his suspicions that the Wendells are connected to the mysterious disappearance of that businessman, but before he can prove anything, the previous unsolved mystery of the range war murders from “The Shepherds” comes back to destroy him. With Dumire out of the way, the Wendells are free to spend their ill-gotten money, investing in land development and real estate — assuredly in ways opposed to Levi Zendt, McKeag, and Pasquinel.

As its name indicates, “The Winds of Death” brings a lot of these later conflicts and characters to a sad conclusion — such is the way of life. The implication that the 20th century is the worst era of the history of the Platte lands is there for the audience to see, but Michener is always optimistic that we can learn from these mistakes and decisions and return to wise stewardship without expecting the land to do what it cannot do. The horrible consequences of demanding too much from the land is displayed during the scariest scenes of the entire series at the close of this episode. Despite warnings from quite old Hans Brumbaugh and almost as old Jim Lloyd, Earl and Alice Grebe buy dry prairie land from the Wendells and try to farm there. Despite his guilt about his family’s past and his association with Dumire, Philip Wendell soon involves himself in the family business of shady real estate banditry, foreclosing on farmers during the crises of World War I and the Dust Bowl — almost making one yearn for the days of Seccombe and the Venneford, which by this time is much smaller than it used to be but has become its most successful in its new incarnation, thanks to industrious Jim and Charlotte Lloyd. During the height of the Dust Bowl, and perhaps the scariest incidental music in the history of television, Alice Grebe goes insane, killing most of her family and is then killed by her husband who then commits suicide. Shortly thereafter, unrelatedly, Jim Lloyd dies and we know the story is almost over.

The Scream of Eagles

By the late 1970s, Centennial, Colorado is barely recognizable from what it once was and now looks very much like a modern American city, still suffering from the Western travails of racial discrimination, opportunism, and the pressures of ecological remediation. Philip Wendell (now played by Robert Vaughn) is, likewise, no longer recognizable from the morally impressionable young boy he was to the late-middle-aged entrepreneur he has become under his parents’ tutelage. In contrast is Paul Garrett (David Janssen on screen, finally, after narrating 11 episodes), current owner of the Venneford Ranch and descendent, somehow, of most of the major characters in Centennial’s history: Messmore Garrett, Jim Lloyd, Levi Zendt, Pasquinel, Lame Beaver, and more. Eventually, Garrett is persuaded to run against Wendell in the upcoming election for Commissioner of Resources, an office that will be responsible for managing the region’s economic growth and historic preservation: the ideologies clashing through the entire saga reach a clear climax.

Meanwhile, Sidney Endermann (Sharon Gless — Cagney, not Lacey) and Lew Vernor (Andy Griffith) arrive to capture the history of Centennial, finding a valuable resource in Paul Garrett. Their inquiries into the land and its inhabitants convince Garrett to run for office against Wendell, in part, because of his growing frustration with governmental treatment of, well, everyone and everything. Instead of giving up or just complaining, Garrett can become part of the system and work effectively to bring about change and restoration: again, the optimistic message of Centennial is clear. During their investigation, Vernor discovers the old cave that houses the corpse of the man Wendell’s mother murdered years ago, frightening Wendell. He, in turn, does his best to smear Garrett during their competing campaigns, but it appears by the end (though never explained explicitly) that Garrett wins, furthering the optimism of the saga. With the future looking bright, provided wisdom and ecological responsibility win out over unbridled acquisitiveness, Vernor and Endermann start writing the history of Centennial, bringing the saga full circle.

Their Story is Our Story

Perhaps you are wondering why I told you the whole story, and why, perhaps, you should bother watching the series now that you know what happens (or why, even, you should read the almost thousand-page novel). Though it might not seem like it, I certainly did not tell you the entire story. A saga like this has many more characters, plotlines, conflicts, and themes that can be adequately summarized here — even the main characters and storylines are much more interesting and enjoyable than the treatment given above. The novel, especially, has a great deal more content than the mini-series has, particularly about the early prehistory of the land and Brumbaugh’s beet industry. The differences between the versions are not terribly important, though Morgan Wendell is a better person in the book than in the mini-series. It is a full, involving, quality story (in both versions), and it should be enjoyed be everyone simply because it is a great story: the characters are real, the history is true, and the ideas are engaging and relevant. Finally available on dvd, though the people who wrote the summaries on the dvd cases sometimes sound like they haven’t seen the episodes, we can watch Centennial whenever we want. Additionally, the retrospective bonus feature is an enjoyable look back with some of the major actors, sharing memories and interesting tidbits of filming this mega-masterpiece; it’s always nice to hear key actors in major roles talk appreciatively of their parts, their fellow actors (especially the kind things Robert Conrad and Barbara Carrera have to say about Richard Chamberlain), and the cultural significance of the work itself. Essentially, though, you should read the novel and enjoy the mini-series for the same reason James A. Michener created the story in the first place. As he says in his introductory monologue

I suppose my primary reason for writing the book Centennial was to ask us, you and me, if we’re aware of what’s happening right now to this land we love, this earth we depend upon for life.… It’s a big story about the people who helped make this country what it is and the land that makes the people what they are. And it’s a story about time, not just as a record but also a reminder: a reminder that during the few years allotted to each of us, we are the guardians of the earth. We are at once the custodians of our heritage and the caretakers of our future.

Centennial is the great adventure of the American West, and this story, their story, is our story. Its message is as true and relevant today as it was thirty years ago. That is reason enough to read it, watch it, and treasure it again and again … for as long as the waters flow.