Fr. James V. Schall

For quite some time, Fr. James V. Schall has been my favorite living author. His On the Unseriousness of Human Affairs and The Life of the Mind are essential reading for everyone who wants to understand what life is truly about. For this last journal, I knew I wanted to get some of his work in here (whether he knew it or not), but I had difficulty choosing which of his essays to include, so I grabbed two mainly at random. I figure he wouldn’t mind.

“It is this same disciple who attests what has here been written. It is in fact he who wrote it, and we know that his testimony is true. There is much else that Jesus did. If it were all to be recorded in detail, I suppose the whole world could not hold the books that would be written.” — John 21:24-25.

“For this reason anyone who is seriously studying high matters will be the last to write about them and thus expose his thought to the envy and criticism of men. What I have said comes, in short, to this: whenever we see a book, whether the laws of a legislator or a composition on any other subject, we can be sure that if the author is really serious, this book does not contain his best thoughts; they are stored away with the fairest of his possessions. And if he has committed these serious thoughts to writing, it is because men, not the gods, have taken his wits away.” — Plato, The Seventh Letter, 344c.

“Books of travels will be good in proportion to what a man has previously in his mind; his knowing what to observe; his power of contrasting one mode of life with another. As the Spanish proverb says, ‘He, who would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry this wealth of the Indies with him.’ So it is in travelling; a man must carry knowledge with him, if he would bring home knowledge.” — Samuel Johnson, Good Friday, April 17, 1778.1

I. We are familiar with the incident in the Gospel of the rich young man who asked Christ what good he must do to be saved. Christ responded to him he must keep the commandments. This the young man had done from his youth, a fact Christ recognized in him. Christ added, in words that still force us to distinguish between “obligation” or “duty” and something more and different from it, if he wanted to be perfect, what he should do was to sell what he had, give it to the poor, and come follow Him. The Gospel records the young man did not follow this proposal, rather he “went away sad,” for, as it says in striking explanation, the young man “had many riches” (Matthew 19:16-23). We might suggest this rich young man was, as far as we can tell, one of Christ’s conspicuous failures along with, say, Judas, one of the thieves, the scribes, Pontius Pilate, Herod, and several of His hometown relatives.

Notice that Christ did not tell the young man to become an entrepreneur so he could create wealth to help the poor, though there is nothing wrong with this avenue. Nor did Christ “impose” a more perfect way on him. It was up to what the young man himself “wanted” to do with his life. Yet, even on reading this famous passage, a passage John Paul II referred to again and again when talking to youth from all countries, we have the distinct impression the rich young man, and perhaps the world itself, missed out on something because of his refusal.

If “ideas have consequences,” so, possibly more so, do choices — even refusals, which are likewise choices. Choices always have objects. There is no such thing as choice for choice’s own sake. It’s sophistry to maintain it is. We can suspect the young man’s talents, without his riches, or perhaps even with them, were needed elsewhere, perhaps later with Paul or Silas. Indeed, Paul was subjected to pretty much the same process, but he decided the other way, for which we can still be thankful as we read his Epistles to the Romans, Corinthians, Ephesians, Colossians, Thessalonians, to Titus and Timothy. After all, when knocked to the ground on the way to Damascus, he could, after his eyes cleared up, gotten back up and walked away.

This memorable account of the rich young man reminds us not only is the world less when we do evil, but even when we do less than we are invited to do. It makes us wonder whether the world is founded in justice at all, in only what we are to render, in what we ought to do. Such a world would be rather dull, I think. It would lack the adventure we now find in it. While not denying their acknowledged worth, the highest things may be grounded in something quite beyond justice. An utterly “just world” may in fact be a world in which no one would really want to live. Justice is, as I call it, a terrible virtue. The fact God is not defeated by evil or even by a lesser good helps us to realize, with some comfort, I confess, we do not find only justice at the heart of what is. The great book that teaches this principle, above all, is C. S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces, a book not to be missed.

My remarks obviously play on these words, “What must I do to be saved?” To be provocative, I ask, “What must I read to be saved?” I do not suggest Christ had His priorities wrong. When I mentioned this question…to a witty friend of mine, she immediately wanted to know whether any of my own books were included in this category of books “necessary-to-get-to-heaven?” I laughed and assured her indeed the opera omnia of Schall were essential to salvation!

The irony is not to be missed. We cannot point to any single book, including the Bible, and say absolutely everyone must actually read it, line by line, before he can be “saved.” If this were to be the case, few would be called and even fewer chosen. Heaven would, alas, be very sparsely populated. But I do think between acting and reading, even in the highest things, there is, in the ordinary course of things, some profound relationship. Acting is not apart from knowing, and knowing usually depends on reading.

II. Concerning books and getting to Heaven, however, let me note in the beginning, statistically, a good number of the people in the history of mankind who have ever been in fact saved were mostly what we today call “illiterate,” or at least not well educated. They were good people who did not know how to read, let alone write books. While Christianity does not at all disdain intelligence — quite the opposite, it thrives on it — still it does not simply identify what it means by “salvation” or “the gaining of eternal life” with education or literacy, in whatever language or discipline. In the long dispute over Socrates’ aphorism virtue is knowledge, Christians have generally sided with Aristotle, that fault and sin are not simply ignorance. Multiple doctorates, honorary or earned, will not necessarily get us to Heaven, nor, with any luck, will they prevent us from attaining this same happy goal.

Just as there are saints and sinners among the intelligentsia, so there are saints and sinners among those who cannot read and write. Christoph Cardinal Schönborn remarked Thomas Aquinas was the first saint ever canonized for doing nothing else but thinking. Yet, within the Christian tradition more than a suspicion exists the more intelligent we are and the more we consider ourselves to be “intellectuals,” the more difficult it is to save our souls. The sin of pride, of willfully making ourselves the center of the universe and the definers of right and wrong, is, in all likelihood, less tempting to those who do not read or who do not have doctorates in philosophy or science than it is to those who read learnedly, if not wisely. The fallen Lucifer was one of the most intelligent of the angels. His first sin was made possible by the order of his thought. No academic, I think, should forget Lucifer’s existence and his sobering story. It is not unrelated to a modern academic scholar. The figure of Lucifer should, in some form, appear on every campus as a reminder.

III. When we examine the infinitive, “to read,” moreover, it becomes clear a difference is found between being able to read and actually reading things of a certain seriousness, of a certain depth. Not that there is anything wrong with “light” reading. Indeed, the subtitle of one of my books, Idylls and Rambles — though again, need I remind you, it is not a book necessary for salvation! — is precisely “Lighter Christian Essays.” The truth of Christianity is not inimical to joy and laughter, but, as I think, it is ultimately a defender and promoter of them, including their literary expressions. I have always considered Peanuts and P. G. Wodehouse to be major theologians. In truth, it is the essential mission of Christian revelation to define what joy means and how it is possible for us to obtain it, that it is indeed not an illusion. The first thing to realize is joy is not “due” or “owed” to us.

J. R. R. Tolkien, in his famous essay “On Fairy-Stories,” even invented a special word to describe this essence of Christianity. We are not, as it sometimes may seem, necessarily involved in a tragedy or a “catastrophe” but precisely in a Eucatastrophe. The Greek prefix “eu” — as in Eucharist — means happy or good. In the end, contrary to every expectation, things do turn out all right, as God intended from the beginning.2 This is why in part the proper worship of God is our first, not our last task, perhaps even in education. In Josef Pieper: An Anthology, a book not to be missed, Pieper remarks further that joy is a by-product; it is the result of doing what we ought, not an object of our primary intention; ultimately, it is a gift.

“Faith,” St. Paul told us, “comes from hearing,” not evidently from “reading,” though this same Paul himself did a fair amount of writing. We presume he intended for us to read it all. It seems odd to imagine he wrote those letters to Corinthians, Romans, Philippians, and Ephesians with no expectation of results. When Paul remarked faith came by “hearing,” he probably did not mean to say it could not come “by reading.” We do hear of people who, as they say, “read themselves into the Church.” Chesterton, I think, was one of these. In classic theology, it is to be remembered, however, that unless we receive grace — itself not of our own fabrication — we will not have faith either by hearing or by reading or, in modern times, by watching television or Internet, themselves perhaps the most difficult ways of all!

Many, no doubt, have heard but have not believed. Paul tells of those, including himself, who, at the stoning of Stephen, put their hands over their ears so they could not hear what he was saying. Alcibiades tells of doing the same thing so he would not hear the persuasive words of Socrates. Christ said to St. Thomas the Twin, “Blessed are those who have not seen but who have believed.” Every time we read this passage, we are conscious we are among those blessed multitudes who have believed but who have not seen. And even our hearing, say in preaching and in Sunday sermons, usually comes from someone who has previously read, and hopefully read well.

The Apostle John affirms at the end of his Gospel, a document itself full of the word, “Word,” — in the beginning was the “Word,” “Word” made flesh — he in fact wrote the words we read and his testimony is true. As Benedict XVI says, “Deus Logos Est.” John also intimates, reminiscent of Plato, that many things are not recorded in books, even in all the books in the world. Yet, as the Church teaches us, the things the Lord taught and did that have in fact been handed down to us are sufficient for us. Sometimes, it is sobering to reflect the entire corpus of the New Testament covers a mere 243 pages in the English Revised Standard Edition. Those of us who are fortunate enough to be literate do not have to be “speed readers” to finish the New Testament many times over during our lives, even in the course of a few days, if we wish.

Whether all the books ever written in this world are contained in today’s libraries, or on the on-line facilities, I doubt. But a tremendous number of them are. One of the main problems with these comments on reading has to do with the sheer amount of books available to read, and yes, to re-read. I am fond of citing C. S. Lewis’s famous quip if you have only read a great book once, you have not read it at all. This pithy remark, of course, brings up the problem of what is a great book and why great books are really “great.” Even more, it asks whether “great” books exist that are not officially called great? Ought we to spend all our time, after all, on so-called “great” books? Leo Strauss once remarked that, in the end, the famed great books contradict each other. This fact led many a philosopher and many a student into relativism under the aegis of philosophic greatness. There are, as I think, “great books” that are not considered “great.”

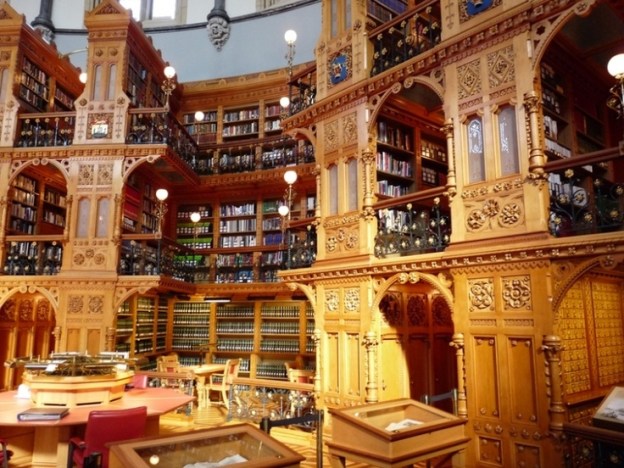

The Web site of the Library of Congress informs us in 1992, the Library accessioned its 100 millionth item. The Library contains books in about 450 languages. I have friends who can handle fifteen or twenty languages. But I do not know anyone who can handle 450 different languages. No doubt considerable numbers of books have been added since 1992, and I do not mention the books in the British Museum or the Vatican Library, or the great French, German, Spanish, American, and Italian libraries, as well as others throughout the world.

When I was about eighteen in the army at Fort Belvoir in Virginia, I went into the post library, with time on my hands. I looked at all the stacks of books, but I realized I did not know what to read or where to begin to find out. It was a kind of revelation to me of that famous Socratic dictum of “knowing what I did not know.” Yet I knew, that, however logical, one did not go to the first book under the letter “A” to begin to read systematically all the books until one reached “Z.” First of all, it could not be done in one lifetime, even in a fairly small library, and secondly it would have promoted a mental hodge-podge.

At the beginning of the Summa, St. Thomas tells the young student an order of learning and knowledge exists that makes it possible to distinguish the important and the unimportant things. No library, I might add, is constructed on the order of St. Thomas’s Summa, which, I suspect, might tell us something about the limits of libraries, however good they might be. Again, we are not well advised to take some encyclopedia and begin with articles under “A” and read to those under “Z.” The order of knowing is crucial to us.

A famous quip claims “any man who says that he has read all the writings of St. Augustine is a liar.” Likewise, if we take St. Thomas, remembering he had no computer and he had at most twenty-six or twenty-seven years of life during which he could write anything before he died in 1274, we still find it almost impossible to believe he actually wrote all he did write. What he wrote was clearly dependent on what he also had read.

I recommend students to go over to the library and look up on the shelves the folio opera omnia of St. Augustine and St. Thomas. Students need to consider what sort of life one would have to lead in order to write, let alone understand, such a vast amount of work. Too, the students should reflect on what different kinds of life from each other these two great intellectual saints lived. Moreover, we shudder to think where we should be as a culture had, like the rich young man, Augustine or Aquinas chosen some other form of life, which they no doubt could have.

The story of how the works of Aristotle or Augustine were saved for posterity is itself another of the scary accounts of how, even though they wrote what they did, we almost lost what they wrote after it was written. Indeed, we did lose much of what Aristotle wrote, not to mention Cicero and other important thinkers. The very dialogue of Cicero that changed the life of the young Augustine, as he tells us in The Confessions, is now lost. We do not have it in the Library of Congress.

I was once on a division of the National Endowment for the Humanities that considered grants to libraries for the physical preservation of books and newspapers. It is astonishing over time how fragile our output of books and papers is, even with great preservation efforts. Of course, all our current “on-line” facilities, in which most of today’s writing and publishing first appears and, indeed, in which it is preserved, depend on a continuous supply of electricity, not to mention computers. It also depends on whether the barbarians get through the gate to destroy it. These latter technologies seem to defy both time and space in enabling us to send our latest thoughts around the world or across the street in an instant. But the question always remains whether we have anything to say and whether what we say is true or not.

IV. Each of my students is required to read what is said to be the most “immoral” expository book in the history of political philosophy. It is also a most famous and enticing book. Students are much attracted to it and by it. Many students, indeed, I have noticed, are charmed by it. I am charmed by it myself. We are naive if we think the difference between good and evil is always easily recognizable, let alone easy to choose between, even when we do recognize it.

This book, of course, is Machiavelli’s Prince. The book originally was given as a gift to the ruler of Florence, almost as if he did not himself know how to rule. It sketched how a prince would sometimes, perhaps often, have to do bad things in order to keep in power. So long as we think it is a good thing to stay in power no matter what, then Machiavelli’s advice becomes a lesson in how to do it, especially on the “no-matter-what” part of his advice. Evidently, in such a view, what makes good men to be bad princes is the restriction on their actions imposed on them by the classical distinctions of good and evil. The prince, liberated from restriction, would presumably be a more “successful” ruler, if not a better man.

In the course of his book, Machiavelli tells us, with some paradox, that all armed prophets succeed and all unarmed prophets fail. At first sight, this teaching will seem quite logical until we remember Machiavelli himself was neither a prophet nor a prince. If this is the case, that he was a minor diplomat and not a prince, it seems paradoxical he thought his own unarmed life was worthwhile. Machiavelli hints his real foes are men who did not write books, namely, Socrates and Christ. Both Socrates and Christ were, moreover, unarmed prophets, as was Machiavelli himself. But Machiavelli did write a book. Neither Socrates nor Christ wrote one.

What, then, can Machiavelli mean when he says Christ and Socrates were “unsuccessful?” Socrates needed Plato to write about him. Christ needed the Evangelists and Paul. Evidently, Machiavelli thought he had to undermine, not the armed prophets, but the unarmed prophets. Who was Machiavelli’s audience, then? Was it Lorenzo, the prince? It hardly seems likely. By writing a charming book, Machiavelli sought to entice generations of students and students-become-rulers to his principles. These readers encounter something that, if they follow its suggestions, will not save them. Machiavelli wrote to turn the souls of potential philosophers away from Socrates and Christ. Unless he could manage this “conversion,” the world could not be built on his “modern” political principles. To follow Machiavelli’s tract, we must cease to be interested, as was Socrates, in immortality, or like Christ in first seeking the Kingdom of God.

Do I think The Prince to be one of the books we must “read” to be saved? I do indeed. The knowledge of what one ought not to do is not a bad thing. It can be, but as such, it is not. It is good to know the dimensions of what is persuasively wrong. We ought to encounter disorder in thought before we encounter it, and especially before we duplicate it, in reality. It was Aristotle, I believe, who remarked virtue can know vice, but vice does not know virtue.

V. What must I read to be saved? When classes were over one spring, I received an e-mail from one of my students who had arrived back at his family home. He wrote:

I have found something interesting while talking to my friends here at home…. Many of my peers have fallen into the trap of moral relativism. They have accepted education as a means to an end. It is very disheartening. I was wondering if you had … any … suggested readings for this subject of the relativism of my generation? Many of my friends feel that religion or spirituality is a private thing, and one ought not question another’s belief system. Everything is personal and therefore out of the realm of criticism. I think someone wrote something about how an affirmation of morality, religion, and ethics as a “private” enterprise, is in itself a moral statement.

No doubt, readers will recognize the sentiment expressed here. It reminds me of the famous passage in Allan Bloom’s 1986 book The Closing of the American Mind: “There is one thing a professor can be absolutely certain of: almost every student entering the university believes, or says he believes, that truth is relative.”3 We wonder: “Does this relativism have a history?”

In a two-frame Peanuts comic strip, Sally is shown sitting upright in a formal chair staring at the television in front of her. From the television she hears the following announcement: “And now it’s time for…” In the second scene Sally, with determination, points the remote control, which looks like a gun, at the machine and firmly announces: “No it isn’t!” The last thing we see is a printed click.4 Sally shoots point blank to kill the monster before her. I cite this colorful little snippet in the context of “what must I read to be saved” because it makes the graphic point we each must simply shut things off in order to come into some possibility of knowing what all that is is about.

So I am going to propose, with some rashness perhaps, a brief list of ten books that, when read, will perhaps save us or at least bring us more directly to what it is that does save us, faith and grace and good sense. The writers of the books I select will all, I think, accept the proposition saving our souls and saving our minds are interrelated. We do not live in a chaos, though we can choose one of our own making.

Basically, I think if there is something wrong with the way one lives, it is because of the way one thinks. However, I am most sensitive to Aristotle’s observation often how we live and want to live prevent us from clearly looking at what is true. Our minds see the direction truth leads and often we do not want to go there. In short, there is no way around anyone’s will, but the shortest way is go follow Sally’s example, click off the screens that keep us in mere spectatorship and take up the much more active occupation of reading for understanding what it is all about.

These, then, are the ten books:

1) G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

2) C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

3) E. F. Schumacher, A Guide for the Perplexed

4) Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

5) Peter Kreeft, The Philosophy of Tolkien

6) Ralph McInerny, I Alone Have Escaped to Tell You

7) Dorothy Sayers, The Whimsical Christian

8) J. M. Bochenski, Philosophy: An Introduction

9) Etienne Gilson, The Unity of Philosophical Experience

10) Josef Pieper: An Anthology

One might object, “Only Dostoyevsky is a classic and it is long. What about John Paul II’s Crossing the Threshold of Hope? Or Benedict’s Encyclical on Love?” Read them! What about the Bible, Plato, and Aristotle? Read them! And Augustine’s Confessions? Never to be missed. What about Schall’s opera omnia? For Heaven’s sake, read them!

I do not want to “defend” my list against other lists. I can make up a dozen other lists myself. The only really long book in my list is Dostoyevsky, which takes some time to read. Gilson’s book requires attention but it is manageable by most people. Most are short, easy to read. All should be read many times. The point about this list, however, as I see it, is if someone reads each of the books, probably in whatever order, but still all of them, he will acquire a sense that, in spite of it all, there is an intelligibility in things that does undergird not only our lives in this world but our destiny or salvation.

Again, a relation exists between what we think and what we do. We can think rightly and still lose our souls, to be sure. But it is more difficult. The main point is the intelligibility of revelation is also addressed to our own intelligence. We need to be assured what we believe makes sense on any rational criteria. Lest I err, a reading of each of these books will point us in the right direction — one that indicates at the same time how much we have yet to know, including the completion of God’s plan for us itself, but also how much we can know midst what often appears as a chaos of conflicting opinion. But to obtain the impact of these readings I intend, one does have to click off the screens and the noises that prevent us from encountering writers, often delightful writers, who so clearly wrestle with the reality of the things that are, including the ultimate things.

Endnotes

1 Boswell’s Life of Johnson (London: Oxford, 1931), II, 227.

2 J. R. R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” The Tolkien Reader (New York: Ballantine Books, 1968), 68.

3 Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), 25.

4 Charles M. Schulz, Could You Be More Pacific? (Peanuts Collector Series #8; New York: Topper Books, 1991.