Christopher Rush

I am no expert on Catholic theology, but I suspect it is easier to solve a problem like Maria than it is to define “beauty” in any authoritative way. Considering in the more than two thousand years since the classical world, no aesthetician, artist, philosopher, critic, or beleaguered junior high art teacher has been able to craft a widely-satisfying definition of beauty, it would be presumptuous to propose one here and now. On the other hand, since the likes of Aristotle, Aquinas, Kant, Hegel, Spinoza, and William James have been unable to conquer this chimera, I will be in good company if I cannot do so either. Instead of attempting to do what the great minds of history have not done, we shall focus instead on advocating beauty as an objective reality as opposed to a subjective one.

Though it is rare for artists and critics to agree on anything, most if not all agree that beauty exists. The difficulty comes with the next step of rhetorical stasis theory: what kind of thing it is. Is beauty subjective or objective? The inability to come to agreement on the nature of beauty is a significant reason why little progress has ever been made in defining it. This age-old question is perhaps most often answered by the commonplace “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” which clearly posits beauty as a subjective concept: the reader, the listener, the viewer of whatever subject is presented for the audience has total authority to determine if the work in question should be considered beautiful, or, perhaps, even is beautiful. The popularity of this saying does not make it, ipso facto, true and authoritative, of course, but it must be acknowledged, and not in my favor for this present argument, that no ready to hand aphorism for beauty’s objectivity exists.

Furthering the complexity of the issue of trying to categorize beauty and its unclear nature as either a subjective or an objective reality, many have suggested that beauty is entwined with truth and goodness, concepts that, at times, are nearly as tenuous to grasp. Mortimer Adler, in the Syntopicon, summarizes the perplexities of this trio of imbricating ideas this way:

Truth, goodness, and beauty, singly and together, have been the focus of the age-old controversy concerning the absolute and the relative, the objective and the subjective, the universal and the individual. At certain times it has been thought that the distinction of true from false, good from evil, beautiful from ugly, has its basis and warranty in the very nature of things, and that a man’s judgment of these matters is measured for its soundness or accuracy by its conformity to fact. At other times the opposite position has been dominant. One meaning of the ancient saying that man is the measure of all things applies particularly to the true, good, and beautiful. Man measures truth, goodness, and beauty by the effect things have upon him, according to what they seem to him to be. What seems good to one man may seem evil to another. What seems ugly or false may also seem beautiful or true to different men or to the same man at different times.

While often grouped together as significant values, whether universal and transcendent or otherwise, beauty is often treated as fundamentally different from its fellows in this trio, as truth and goodness require much more important responses than beauty. People tend to find it easier, generally speaking, to disregard a beautiful work if it doesn’t fit their fancy than it is to ignore right conduct (goodness) or truths about existence (again, generally speaking – we all know humanity is excellent at lying to itself and, as Paul says in 1 Corinthians, incapable of understanding spiritual truth).

For Christians, especially those who eschew the notion that man is the measure of all things, as Adler noted above, truth and goodness are not (or should not be) so inscrutable, but beauty remains elusive even for many of us. If beauty should be collocated with truth and goodness, one might be inclined to consider it an absolute value and thus objective, but the dearth of Bible verses on beauty, especially in an aesthetic sense and related to the created artworks of man or even in elements of nature itself, tends to disincline many Christians from embracing beauty as easily as truth and goodness. Jesus was, after all, the Truth and the Good Shepherd (cf. John 14:7, 10:11), but Isaiah points out He had “no beauty that we should desire him” (Isaiah 53:2, ESV). If Jesus was not beautiful, why should we spend effort exploring what is? This rather dextrous use of logic to pursue heavenly holiness and avoid worldly endeavors is a rather recent notion within the church, and it inspired Christian thinkers in the latter half of the twentieth century, such as Hans Rookmaaker and Francis Schaeffer, to encourage Christians to once again engage in the arts and delight in beauty wherever it could be found without guilt.

Returning to the seemingly subjective notion that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, closer examination of this saying reveals that the beholder is required to make a judgment. The beholder has to perceive the object of beauty and decide that it is beautiful. If the saying wanted to convey a passive acknowledgement of the truth of the beauty of the object being observed, it would be self-defeating by implying the object is innately beautiful and the observer’s role is simply to observe that it is beautiful, free of judgment. As it stands, then, the saying advocates beauty as subjective, but in order for beauty to be subjective, the observer has to make a rational judgment to that end.

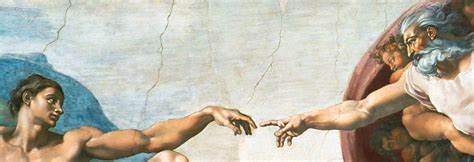

It is this aspect of perceiving beauty, rational judgment, that drives much of Roger Scruton’s analysis of beauty in Beauty: A Very Short Introduction. “The judgement [sic, passim] of beauty, it emerges, is not merely a statement of preference. It demands an act of attention. … Less important than the final verdict is the attempt to show what is right, fitting, worthwhile, attractive or expressive in the object: in other words, to identify the aspect of the thing that claims our attention.” Scruton spends much of his book demonstrating that acknowledging beauty where it is seen is not merely a matter of taste, which would be wholly subjective. Beauty can be found in various aspects of reality: nature itself; man’s attempts to systematize nature through well-kept gardens and aesthetically-pleasing architecture; works of fine art such as paintings, sculpture, poetry, music, and, perhaps, cinema; and even in everyday objects of fine craftsmanship that promote balance and order, two additional companions of beauty.

The discussion of nature being beautiful acts as an effective foundational argument for beauty’s objectivity. In the appreciation of nature, says Scruton, “we are all equally engaged, and though we may differ in our judgements, we all agree in making them. Nature, unlike art, has no history, and its beauties are available to every culture and at every time. A faculty that is directed towards natural beauty therefore has a real chance of being common to all human beings, issuing judgements with a universal force.” Scruton emphasizes the existence of nature as the main point here: since it exists apart from mankind as its usual observer, individual responses are not authoritative. The claim “I don’t think Impressionist paintings are beautiful” warrants discussion in the subjective/objective debate here, but “I don’t think waterfalls are beautiful” is less tenable, in part because of that universal quality of nature Scruton mentions. Nature is. Disliking how reality is does not contribute anything for anyone, even the person hewing to that idea. The person who says, “I do not enjoy reading Newton’s Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy” is worth debating; the person who says, “I am not a fan of gravity” may best be left alone, at least for a little while. If nature is beautiful, beauty exists separate from our subjective responses to it. Natural beauty existing in places people cannot see is troublesome to Kant: “how are we to explain why nature has scattered beauty abroad with so lavish a hand, even in the depth of the ocean where it can but seldom be reached by the eye of man – for which alone it is final?” Christian aesthetes would likely respond that man is not the final eye for observing nature anyway, and the hand that scattered beauty abroad so lavishly belongs to the One who created it for His own good pleasure as well as out of love to share it with His creations. In any event, if beauty exists where our eyes cannot observe it, beauty does not depend on our subjective responses after all.

Those who acknowledge nature as beautiful (or sublime) may even credit the universal quality of nature Scruton highlights, while still raising the objection that man-made realms of art can be legitimately received or designated subjectively. Nature is one thing; those Impressionist paintings and laborious prose of scientists and theologians is another, as we have acknowledged above. “You like Bach, she likes U2; you like Leonardo, he likes Mucha; she likes Jane Austen, you like Danielle Steele,” as Scruton puts it. This returns us to the fundamental tenet of beauty’s subjectivity: personal taste, if not the only standard, is at least an acceptable standard for aesthetic judgment, and once that is averred, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” soon gives way to “anything can be art,” and before one can say Milton Cross the barbarians are not only through the gates but also they are using The Adoration of the Lamb as a placemat under their chicken fried waffles. Weak attempts at humorous hyperbole aside, Scruton seriously attempts to forestall such a decline into banality by presenting the other sources of beauty (cultivated nature in gardens and such, everyday objects of fine craftsmanship, and, perhaps most significantly, the fine arts) as objective beauty-realities just as nature is. His defense of these areas often confront the question of subjectivity through the idea of purpose – not just the telos of these discrete human endeavors in isolation but also the purposeful implications for us as people in pursuing these endeavors the way we do – and that purpose never seems to be enough for mankind.

The drive to reshape nature into gardens, parks, manicured lawns surely speaks to a universal yearning for beauty and order, even if not everyone enjoys pulling weeds and gassing up the lawnmower. Turning the wilderness around us into an orderly space for the kinds of flowers we prefer and a navigable path to the hot tub and charcoal grill does not deny the innate beauty of nature; rather, it demonstrates a desire to inhabit beauty and make the spaces in which we exist orderly and enjoyable. “This attempt to match our surroundings to ourselves and ourselves to our surroundings is arguably a human universal,” Scruton says. “And it suggests that the judgement of beauty is not just an optional addition to the repertoire of human judgements, but the unavoidable consequence of taking life seriously, and becoming truly conscious of our affairs.” The purpose of gardens is not to show nature and entropy who’s boss; it is to increase beauty wherever we can. Likewise we design buildings with flair and style, Bauhaus and Minimalism fads aside, because not only do we need space for our things and places to work but also we want to work in attractive places. Few have faulted the exterior of the Sydney Opera House for being non-functional. The skylines of Florence, Italy and Dubuque, Iowa may not normally be placed in propinquity like in this sentence, but both are marked by centuries-old architecture designed to delight as well as function, supplied mainly by buildings that exist for religious purposes, interestingly enough. It is telling that for most of Western civilization, when lifespans were markedly short, architecture and furniture were marked by a commitment to beauty beyond utility and materials meant to last (marble and oak). Today, with lifespans ever increasing, architecture is a hurried affair of bland rectangles and pressed-wood bookshelves. Telling as well that the cars of the ’50s and ’60s are still beloved collector’s items, not for their gas mileage and cup holders, but for their fins and freshness and beautiful originality. Some people, at least, still think beauty is worth the material and temporal cost.

The same can effectively be said for everyday use objects and their connection to beauty, especially as shown through function and order and enhanced by flair. Scruton uses the example of setting the table for guests: “you will not simply dump down the plates and cutlery anyhow. You will be motivated by a desire for things to look right – not just to yourself but also to your guests.” Sometimes we engage in fellowship on paper plates and plasticware (often when s’mores and fireworks are on the agenda as well), but we also know that fine china exists to “get the job done” when the occasion is special and beauty enhances the experience. Just like we do not wear a tuxedo everywhere we go, we do not use the fine china for every meal – but even the regular plates and glasses have a pattern and an etching because the necessity of utility is not enough (assuming one is not a single twenty-year-old thriving on mac-n-cheese and cola).

Of course, the main subject under investigation for beauty being subjective or objective is the world of the fine arts. It is mainly in the realm of art that beauty and the beholder’s eye is called into question. Many people who cannot stand the opera are quite willing to enjoy a sunset and those fireworks, as well as recognizing the value of setting a nice table for Thanksgiving, perhaps even willing to call those things beautiful (even if accompanied with “in their way”). So it is to art we finally turn in our exploration of beauty as objective and not subjective.

Though much has been said about art, beauty, purpose, subjectivity, and objectivity for thousands of years, as noted at the outset no one has authoritatively put the full stop on the debate. Without trying to sound like begging the question, we have summarized the argument for subjectivity in the apothegm “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” which has transformed in practice into “anything can be art.” The merits of subjectivity in art and thus beauty are mainly the appeal to personal freedom, which people enjoy “because it seems to emancipate people from the burden of culture, telling them that all those venerable masterpieces can be ignored with impunity, that TV soaps are ‘as good as’ Shakespeare and Radiohead the equal of Brahms, since nothing is better than anything and all claims to aesthetic value are void.” It does not take long for this aesthetic relativism to expand into moral relativism and, in all sincerity, suddenly the world is not fit for man nor beast. Even if people clamor to live that way, Christians, especially, should not sit idly by and allow that to happen (any more than we have since Modernism).

Instead, let us examine the consequences (yea, benefits) of art and beauty as objective. In his forgotten yet still trenchant essay “The Trivialization of Outrage,” Roger Kimball thoroughly details the squeamish world of what passed for “modern art” at the close of the twentieth century. Though he does admit beauty is “by no means an unambiguous term,” Kimball clearly demonstrates that so-called art that has rejected beauty and attempts only to shock and outrage is not art at all, just as philosophy that has rejected truth as a valid end or objective reality is no true philosophy. “Art that loses touch with the resources of beauty is bound to be sterile,” says Kimball. Art allied with beauty is the only path for art’s restoration as well as the restoration of our well being culturally: “The point is that, in its highest sense, beauty speaks with such great immediacy because it touches something deep within us. Understood in this way, beauty is something that absorbs our attention and delivers us, if but momentarily, from the poverty and incompleteness of everyday life.” It may almost be worth considering beauty as objective simply from a desperate sense of survival, but surely it is more than that: beauty does not just mean an escape from death, it enables and ennobles life itself.

Kimball’s injunction for art’s allegiance to beauty as an attention-arresting experience returns us to our earlier observation that absorbing beauty, whether found in nature or art or anything, is an intellectual process, even when purportedly in the eye of the beholder. Returning as well to Scruton, he refrains from engaging with this key slogan of beauty’s subjectivity until his concluding chapter, and his summary response to that position

is simply this: everything I have said about the experience of beauty implies that it is rationally founded. It challenges us to find meaning in its object, to make critical comparisons, and to examine our own lives and emotions in the light of what we find. Art, nature, and the human form all invite us to place this experience in the centre [sic] of our lives. If we do so, then it offers a place of refreshment of which we will never tire. But to imagine that we can do this, and still be free to see beauty as nothing more than a subjective preference or a source of transient pleasure, is to misunderstand the depth to which reason and value penetrate our lives.

Beauty, clearly, is more than just personal taste. It is a rational means of experience and interpreting reality itself, both in nature (God’s handiwork) and art (man’s handicraft), and because of that, it must be an objective reality, and our aesthetic judgments can only be meaningful in an allegiance to objective existence.

The issue of beauty’s subjectivity or objectivity might be related to C. S. Lewis’s argument for a transcendent moral reality in the broadcasts that became Mere Christianity. Lewis argues it is fundamentally irrelevant that people disagree on what is right and wrong – the important issue is that people, by engaging in such debate even internally, thereby acknowledge right and wrong exist, and thus a meaningful standard for evaluation and distinction must also exist. This is similar to Scruton’s point with judgments of beauty: we tend to get distracted by the particular things called beautiful or ugly (“we may differ in our judgements”), forgetting that even attributing this quality to something can only be done if it exists and if a meaningful standard for warranting that application exists. As morality must exist within an objective standard else we would have no basis for calling one thing “good” and another “bad,” just so an objective standard for beauty must exist. Otherwise anything could indeed be art, and the very terms “art” and “beauty” would have no meaning. And while some “artists” today may be committed to that chaotic end, everyday delight in beautiful objects and man’s continued desires to “look good” and enhance function with flair continue to combat that appetite for destruction.

Let us delight, instead, in beauty’s objective existence, and that art is an accessible means of flourishing beauty in our lives. As Hegel says, the aim of art

is placed in arousing and animating the slumbering emotions, inclinations, and passions; in filling the heart, in forcing the human being, whether cultured or uncultured, to feel the whole range of what man’s soul in its inmost and secret corners has power to experience and to create, and all that is able to move and to stir the human breast in its depths and in its manifold aspects and possibilities; to present as a delight to emotion and to perception all that the mind possesses of real and lofty in its thought and in the Idea – all the splendor of the noble, the eternal, and the true…

From the heart to the head and throughout the soul, all of this wonder and delight and joy (and more) comes to us from objective beauty.

Bibliography

Adler, Mortimer. “Beauty,” in Syntopicon, vol. 1. Edited by Mortimer J. Adler and Philip W. Goetz. Second Edition. Vol. 1. Great Books of the Western World. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1990.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. 1886.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgement. Edited by Mortimer J. Adler and Philip W. Goetz. Trans. James Creed. Second Edition. Volume 39. Great Books of the Western World. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1990.

Kimball, Roger. “The Trivialization of Outrage.” In Experiments Against Reality. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000.

Scruton, Roger. Beauty: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.