Christopher Rush

“And I’ve finally found a place to call my own”: From Genesis to Revelation and Trespass

The early days of Genesis set the scene for this band’s unusual dual nature, in that they appear to mimic typical trends of Progressive Rock, yet they do it in their own unique way. Just as many future band mates find each other at school (seemingly at some sort of art college, where like-minded aesthetics-driven individuals already predisposed toward non-traditional workforce occupations and hobbies tend to congregate), the core of Genesis (Peter Gabriel, Tony Banks, and Mike Rutherford, along with initial guitarist and driving force Anthony Phillips) met at Charterhouse School, what the British call a public school (what we call a private school). The difference for Genesis, then, is they met at effectively a “posh” school for children of well-to -do British society, unlike many others (Jethro Tull, for example, formed from a core of grammar school students Ian Anderson, John Evan, and Jeffrey Hammond). This imbricates with another initial difference for Genesis, in that they met each other while still minors, and most other Prog rock bands met each other when at a college or in their twenties. Genesis’s music matures while the band members themselves are maturing into adulthood.

Another Prog rock distinction of Genesis, as their name implies, is their religious … “affinity” is too strong a word; perhaps “acceptance”? “tolerance”? (if we could dissociate it from its unfortunate connotations in our day). Anthony Phillips says, “we weren’t particularly religious, we just liked the hymns and tunes.” They certainly do present religious themes and allusions more positively and more frequently than most of their Prog compatriots, at least, and their debut album, From Genesis to Revelation, is a good example. While it is still likely true (forty years on) that many Genesis fans are “Invisible Touch”-era fans, and may not know that Gabriel-era Genesis albums exist, it is just as likely that many Gabriel-era Genesis fans do not know From Genesis to Revelation even exists, especially as it technically belongs to their first manager Jonathan King and was not re-released in the anniversary Genesis box sets back in 2007. While the album sounds very much like a juvenile outing, Peter Gabriel’s voice is a foreshadowing of greatness to come (much like the first time James Cagney appears on-screen in The Public Enemy, and one instantly recognizes what a real actor looks like).

The album is lyrically influenced by the Bible, as its name indicates as well as the general proto-concept-like nature of the album, telling a rough musical version of sweeping themes of the Bible (more or less – no verses or characters are quoted, really, but the general impression of Biblical allusion and influence is inescapable). Phillips says the interlinking music to unify it as a concept album came from the hymns, especially J. Herbert Howell hymns, they all loved. Giammetti says Gabriel’s reference to the “happiness machine” in “Am I Very Wrong?” comes from Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine, which fits with what we know of the band’s general love of literature, though no one seems to know who wrote the lyrics for that song specifically.

Giammetti reinforces their early love of science fiction during the focused writing of Trespass (as Genesis, fully committed to being professional musicians, moves to their third drummer, John Mayhew, before Phil Collins): “The only moments of distraction involved walks in the surrounding countryside and reading sci-fi novels and books on mythology (which would greatly influence their lyrics).” Giammetti further says the album features “literary references to movements such as Surrealism and authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and Lewis Carroll (for the fairy tale themes) and William Blake (for the visionary aspect).” It would be wonderful if he quoted the band members to verify this, but he does not.

More helpfully, though, Tony Banks says of his composition “White Mountain” that “Both Fang and another character in the lyrics, One Eye (already mentioned in ‘One-Eyed Hound’ [unreleased single in From Genesis to Revelation days]) come from the children’s book White Fang by Jack London.”

Even by this early stage in their development, Genesis is recognized as “one of the country’s ‘thinking’ bands,” says Michael Watts in a Melody Maker article from January 23, 1971. Surely the lyrics are a significant factor in that assessment, and even if direct or obvious literary allusions were not replete, the atmosphere Genesis songs creates from their outset distinguishes them as a literary band. Gabriel, describing them in that same Melody Maker article, says “I see the band as sad romantics, you see.” Mike Barnard, temporary Genesis guitar player between Anthony Phillips and Steve Hackett, says he and Gabriel would “tour the Lake District” between tour gigs at this time. Surely that is proof of the Romantic poets’ influence on fledgeling lyricist Peter Gabriel.

“Can you tell me where my country lies?”: Nursery Cryme, Foxtrot, Selling England By the Pound, and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

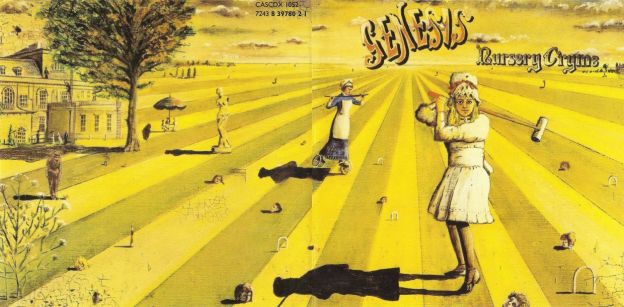

Genesis hits the jackpot with drummer number four, Phil Collins, and guitarist number three, Steve Hackett (not ignoring that Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford had been playing guitar on their albums from the beginning), and in the next few years create four unique, exquisite albums not just for Prog rock but for all music. Nursery Cryme, especially because of the menacing cover art from Paul Whitehead, establishes a darkling Britishness and experimentation that definitely comes through in the music and lyrics. Giammetti says “The Musical Box” is inspired by Oscar Wilde and Peter Gabriel’s Victorian mansion in which he grew up, with “Harold the Barrel” likewise displaying a Dickensian flair.” Steve Hackett offers more specific literary influence for “Seven Stones,” confirming the eclectic reading habits of his new lead singer, saying, “Pete was interested in the ideas he had read in the I Ching, so the lyrics were influenced by The Book of Changes.” Tony Banks corroborates Giammetti’s earlier generalization of the band being influenced by mythology for the final song on the album, “The Fountain of Salmacis”: “The lyrics are based on the myth of Salmacis and Hemaphroditus.” Mike Barnes specifies this is the version in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, book four, and there is no reason to discredit this, considering their Charterhouse education and corroborated experience with mythology.

Foxtrot opens with what I have been telling students for years is Peter Gabriel’s reference to Keats’s great poem “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” but Giammetti and Barnes both credit Tony Banks with writing the lyrics, influenced by Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End and the Marvel comics character The Watcher. As deeply as that wounds my heart to learn, at least there is still a definite literary influence (and mild assuagement from the discovery that Genesis members read Marvel comics).

This album’s lighter fare, “Get ‘Em Out By Friday,” bears influence of science fiction, especially in the ending of “Genetic Control” requiring all people be no taller than four feet to enable smaller, more profitable government housing. Gabriel says, “I tried to put some sort of Dickensian feel into this song,” which may at least tenuously count as literary influence here.

Many sources historical, literary, and religious influenced “Supper’s Ready,” Genesis’s great Prog epic (in the shorter category of single album-side epics such as “Tarkus” and “2112,” as opposed to entire concept albums such as A Passion Play and The Lamb). Though Gabriel says the ending is a “mixture of Christian and Pagan symbolism,” I have no qualms tearing up every time I hear it in sound theological anticipation of a future historical truth when “the supper of the Mighty One” occurs, whether eggs are served or something else.

Of Selling England By the Pound Giammetti says “the usual references to mythology and literature are relegated to a marginal role (albeit still present) in favor of historical references and social comment,” which is certainly in keeping with other de rigueur Prog rock inspirations. This dynamism from Genesis comes at a time, says Giammetti, when Prog rock is starting to lose its way: ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery he calls “passable,” Yes’s Tales from Topographic Oceans “heavy-going,” Rick Wakeman’s solo Six Wives of Henry VIII “indigestible,” and Jethro Tull’s A Passion Play “pretentious,” all of which “confirm that delusions of grandeur had hijacked the musical genre which seemed to be merely running its course and becoming increasingly unpalatable….” Little wonder new sounds like Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, the Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Birds of Fire, and Fripp & Eno’s No Pussyfooting being so popular, and Glam rock peaking at the time as well.

In contrast to all these, Giammetti has nothing but superlatives for this album, with which I agree. Despite the contemporary satirical nature dominating the album, some literary influences and understandings affect the album, evidenced in Gabriel’s alliterative humor throughout the lyrics, surely influenced by his love of Spike Milligan and the Goon Show. The most overt literary influence is in “The Cinema Show,” written by Tony and Mike, in which the romantic overtures of Juliet and Romeo (the literary influence here should be obvious) are followed by recollections of father Tiresias, inspired either by several classical authors or, as Giammetti says, T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Either is credible.

As a postscript to this album, Gabriel remembers the cover artist, Betty Swanwick, as “a little bit like Miss Marple or an[other] Agatha Christie character.” Even if few literary allusions appear on the socio-critical album, it seems Gabriel was often seeing and interpreting his world through literary lenses.

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway would take its own paper to unpack all of the literary and cultural references throughout Genesis’s double-album concept magnum opus. Rutherford had proposed their concept album be based on The Little Prince, but Gabriel insisted on composing an almost all-new epic story, and as a twenty-four-year-old British public school grad, who better to tell the story of a Puerto Rican graffiti artist in New York City? Says Gabriel, “The story is like The Pilgrim’s Progress but on the streets of New York. So it’s a spiritual journey into the soul but there’s quite a tough world feeding the imagery. One of the influences was a film called El Topo by Alejandro Jodorowsky.” Steve Hackett agrees with the spiritual backdrop of this story, reminiscent of “Supper’s Ready,” in that there is “something about the lyric that owed a bit to Dostoevsky – the redemptive qualities of those journeys and sojourns.” While Hackett sees positive spiritual messages in the album, he also recalls how the album and the subsequent tour, and the rest of the band agrees, was a miserable, destructive experience, foreshadowing Roger Waters’s single-mindedness of The Wall and its effect on Pink Floyd.

On a positive literary note, The Lamb surely displays Gabriel’s affinity for the Romantic poets, echoing Keats with “The Lamia” and Wordsworth in the opening line of “The Colony of Slippermen” with “I wandered lonely as a cloud.”

After Gabriel and Hackett departed Genesis, despite early hurts, all members of the band have since reunited both for concerts and interviews, and all of which have seemed more than cordial. Though they all shifted away from Prog rock, their commitment to literary influences has continued. For example, Hackett’s solo album Voyager has a song “Narnia,” surely based on the stories of C.S. Lewis. Gabriel’s “Rhythm of the Heat” was based on his reading of Carl Jung’s Memories, Dreams, and Reflections, and “Mercy Street” is clearly a response to Anne Sexton’s poem “45 Mercy Street.”

“It’s only knock and know all, but I like it”

The members of Genesis were (and presumably still are) well read, and their engagement with fiction, poetry, religion, and philosophy (not to mention the images, environments, history and political ideas of their British world) has resonated throughout their unique careers, especially during their Progressive rock days. Steve Hackett observes, rather poignantly, that this literary aspect of Genesis may have been a barrier to any major success during that time: “If you read the classics, that was a chance you’d enjoy what Genesis did. The criticism was that it sounded like it had been looked up in books rather than it being a personal experience.” If I may end with a Gabriel line from “Back in N.Y.C.” in The Lamb, “Ah, you say I must be crazy,” but that is a significant part of the reason why I love Prog-era Genesis: I have read the classics and the Romantic poets and sci-fi authors that inspired these fellows, and their music is, despite what those critics say, very much a personal experience.

Bibliography

Barnes, Mike. A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & The 1970s. London: Omnibus Press, 2020.

Giammetti, Mario. Genesis 1967-1975: The Peter Gabriel Years. Kingmaker Publisher, 2020.

Weigel, David. The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Progressive Rock. New York: Norton, 2017.