An Annotated Discography

Christopher Rush

Early Days, 1968-70: This Was, Stand Up, Benefit

Like many if not most mid-’60s British bands, Jethro Tull began in a musical admixture of upstart American blues and early rock, European classical heritage, jazz, skiffle, folk, and whatever one was supposed to do about the Beatles. Also like most British bands of the era, Jethro Tull was not the first incarnation of the group nor did its personnel lineup stabilize until many years into fame (though “lineup stability” for Jethro Tull is a complicated notion). Each of these first three albums featured different lineups, if not formally: John Evan and David Palmer may not have been “official” members on Benefit, but they contributed significantly (David Palmer also contributes in minor ways to the first two albums … I said it was complicated).

This Was is easy to call atypical Jethro Tull, looking backward at fifty years of output, but “typical” Jethro Tull is just as complicated an issue as who is in Jethro Tull. It is clearly a heavily blues-inspired album, which is what Mick Abrahams wanted Jethro Tull to be, but it was not what Ian Anderson wanted, and history clearly shows who won that debate. Many of the songs are effectively community property of the British blues scene at the time, many numbers are instrumentals, and Ian Anderson did not write the lyrics to many of the other songs, so identifying influences here is rather fruitless.

Stand Up sounds now like a transition from the mandatory blues origin to what established Tull was going to be, though that is also from the benefit, so to speak, of hindsight. While some blues influences remain, notably on “A New Day Yesterday,” a song not-too-subtly comments on the band’s new direction, it is still an album of a band finding its footing, and many of the songs are about Anderson and the new group discovering that direction. That is not to say it is autobiographical, but there is, still, very little literary influence on this not-quite-yet progressive rock album. Glenn Cornick, fifty years later, indicates much of the album is autobiographical in a different way: “Half of Stand Up was about Ian’s family….” One notable future live favorite song, “Bourée,” “was the first recording clearly to indicate Anderson’s interest in music from earlier historical periods,” which will be helpful for the band’s forthcoming musical and lyrical influences.

Benefit is another unusual album marked by growing pains: pressures of recording and touring now as a headline act instead of a supporting act, personnel burnout, and Anderson’s development as composer and lyricist. Many fans seem to enjoy it more for the songs that are not technically on it: “Sweet Dream,” “17,” “The Witch’s Promise,” and “Teacher.” Glenn Cormick says the autobiographical tendencies from Stand Up are still on Benefit. Ian Anderson confirms this on songs such as “For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me” and “To Cry You a Song.” Audiences seem to assume the non-autobiographical songs are the ones about Anderson (the future cover paintings on albums all featuring miscreants looking just like Anderson did not help that misconception throughout the ’70s.) Other lyrics, such as in “Play in Time,” Anderson flat out reviles as jejune. For our purposes, as fine as it is, Benefit does not live up to its name.

Concept Days, 1971-73: Aqualung, Thick as a Brick, A Passion Play

Aqualung is undoubtedly Tull’s “breakout” album, many fans’ favorite, and greatly misunderstood, either by fans or by Anderson himself. Despite more personnel turnover, Tull begins the ’70s with a masterpiece, which may or may not be a concept album. Side one, called “Aqualung” on the album, features an almost Chaucerian cavalcade of characters, if the Tabard Inn had been in the red light district. More importantly, we finally have actual literary influence on the lyrics: Anderson paraphrases “a line from the introduction of Robert Burns’ [sic] poem ‘The Holy Fair,’” foreshadowing Anderson quoting Burns on Heavy Horses. “Mother Goose” references the eponymous character and Long John Silver, but since Anderson admitted he had never read Stevenson and the no nursery rhyme characters appear in the song, it is likely just Anderson’s general awareness of things that inspired this song over direct literary influences. (The newspaper album cover for Thick as a Brick has a reference to Silver, a parrot, and “Jim Lad,” so perhaps Anderson was recalling the Disney movie more than the novel itself.)

The second half, “My God,” is a fascinating half of an album as a Christian to listen to, but if Scott Nollen is correct, it does not help us here at all: “The material on the album’s second half resulted from Anderson’s personal observations about organized religion, not from any deliberate bookish study. … Anderson proves that he came to the same conclusion as did Freud and [Bertrand] Russell … without reading any of their famous works….” That ends that. Though this quest for the literary influences on Prog Rock may not be as fruitful as I had initially hoped, perhaps it will lead to a more worthwhile exploration in another course about the relationship between Prog Rock and religion. This is also the first Tull album that suffers, in a sense, from the medium limitations of vinyl albums: “Lick Your Fingers Clean” was supposed to end the album but cut for time; now on the cd and digital releases, the song reshapes the album with a much more upbeat and self-effacing ending as opposed to the downcast “Wind-up.”

Thick as a Brick is Anderson’s response to those who considered Aqualung a concept album: here is a genuine Tull concept album, albeit a parody of the form, complete with newspaper and persona singing the song (considered at times two only because of the limitations of the medium – the liner notes treat the whole thing as one poem by Gerald Bostock), all as a satirical sendup of British education. Barrie Barlow, who had played with Anderson and Evan in pre-Tull days replaces Clive Bunker on drums, either solidifying “classic Tull lineup pt. 1” until John Glascock replaces Jeffrey Hammond on bass for Too Old through Stormwatch. Lyrically, TaaB is complex, perhaps too much so, but the album really is an impressive unity between the music and the lyrics, certainly more than any Tull album before and possibly since, depending on how one views Songs from the Wood. More than Aqualung, TaaB fulfills the multi-movement suite typical of Prog Rock, and this is likely better understood today in disc and especially digital versions of the album that break the sections down into more accessible sections.

The song features a number of allusions to literary types, if we can consider comic book heroes such as Superman and Robin “literary,” and it references poets as a social class, though that does not give us much direct assistance. Anderson/Bostock references Biggles, from the British childrens’ book series, though it may be a stretch to call that a literary influence, since it is possible Anderson is mentioning it the same way I might reference to TeleTubbies or Bluey, only as a kids’ pop culture thing I have vaguely heard about without any specific knowledge. Likewise, a reference to the Boy Scout Manual cannot be considered for our purposes as an “influence.” The album cover and newspaper are also rife with clever allusions to general knowledge, such as a “silent prayer” by Billy Graham to close the broadcast day of BBC2 and Alaister Crowley as a special guest on the program “Bible Stories,” though it is, again, hard to call these literary influences. The song features brilliant lyrical moments, as Anderson often does, such as the “wise men” not knowing how it “feels” to be “thick as a brick,” cleverly combining wisdom, feelings, and intellect, but the search continues for major literary influences.

A Passion Play is a somewhat hastily salvaged album from terrible experiences in Switzerland following the success of TaaB. Whereas Deep Purple turned their Swiss discomfort into the incomparable Machine Head, Tull scrapped most of their Swiss creativity until decades later for the rarities album Nightcap and the 40th anniversary box set of Passion Play. Like TaaB, Passion Play is a Tull concept album, but unlike TaaB it takes itself seriously (excepting the beast fable smack in the middle), which is likely why critical response to this is less positive, despite its criticism of religion. The album is intelligently structured, using classical epic ring composition or chiastic structure, as the songs mirror each other until the turning point of “The Hare that Lost its Spectacles.” The album opens with dying heartbeat sounds and closes with reborn heartbeat sounds, mixing the classical epic chiasmus with the its namesake of a medieval passion play thematically. Rolling Stone writer Stephen Holden recognized “a pop potpourri of Paradise Lost and Winnie the Pooh, among many other literary resources,” but that only returns us to what we are trying to avoid, merely recognizing literary similarities in the lyrics. The song asks “how does it feel to be in the play?” but that does not prove Anderson is conjuring up his inner Jacques from As You Like It. There is, though, at the end, the line “Flee the icy Lucifer. Oh he’s an awful fellow!” Aside from the Andersonian downplaying of the seriousness of perdition, if this is not a reference to Dante’s depiction of Lucifer trapped in ice in the Divine Comedy, I would be astounded, for who else conceives of Lucifer as icey?

Eclectic Days, 1974-76: War Child, Minstrel in the Gallery, Too Old…

War Child is an odd, eclectic album, sandwiched among four very unified albums, distinct from Passion Play in part due to the band’s poor reception of critics’ poor reception. Even though the album is structurally distinct from Passion Play, it is thematically similar: songs discuss mortality, morality, femininity, masculinity, VD, tea, musical critics and other beasts, patriotism, and more. Lyrics even allude to life’s “passion play,” as a couple of songs were salvaged and repurposed from the disastrous days before Passion Play, so it is a bit arbitrary to designate War Child into a new “era” of Tull albums. The cover picture, central to many other Prog Rock bands and album meanings, here presents Anderson’s “jester” persona, which becomes a staple of albums and concerts for several years (“Back-Door Angels” has the lines “Think I’ll sit down and invent some fool / some Grand Court Jester” – most likely this is, at least in part, typical Andersonian religious criticism. For someone who claims to be an atheist, he spends a lot of time writing, singing, and thinking about religion). While featuring the first overt nods to his homeland of Scotland that will be more developed in Stormwatch, lyrically, on the whole, it is hard to discern any meaningful literary inspiration here.

Minstrel in the Gallery is an entry somewhere on that ambiguous Venn diagram of concept album, thematically unified album, frame story, or just Prog Rock-era multi-movement suite. It also features the first overt reference to mythology in “Cold Wind to Valhalla.” As discussed earlier, calling even overt references to mythology “literary influence” is a stretch, at least until we get to Genesis. “This is based on old folklore,” says Anderson. “In Norse mythology Valhalla was a huge afterlife hall of the slain, overseen by the god Odin, to which Valkyries took warrior heroes when they died.” So Anderson has a working knowledge of Norse myth, at least. The rest of the songs are primarily fabrications of Anderson’s creativity. We are well beyond his need for lyrical autobiography, and nothing else on the album can be considered literarily inspired.

Too Old to Rock’n’Roll… finally sees the arrival of John Glascock and the “classic” Tull lineup for many, or at least its final phase. It is also a candidate for the aforementioned Venn diagram, as perhaps an obvious concept album, though no one seems to think of it that way, or perhaps a heavily unified album, but it was also originally intended to be a stage musical that somehow transformed into a comic strip illustrated by Dave Gibbons (of Watchmen fame) and a television special. When Anderson sang “Nothing is Easy,” he was not kidding. Much of the album is more Anderson observations of real life, teevee, and car racing, but side one ends with an acknowledgment of literary and musical influences. Anderson says of “From a Dead Beat to an Old Greaser” “the two characters are archetypal social stereotypes from my formative years – the dead beat, in other words the kind of Jack Kerouac follower and imitator, … someone who is into jazz and poetry and whatever but is just fantisising [sic] and has become a bit of a down-and-out; and the old greaser who is the rock‘n’roller motorbike guy. … It’s a sort of Jethro Tull three-minute quickie Waiting for Godot.” Though we may have to collate his reference to Beat Poets with the general references to Mother Goose and mythical characters, we will gladly take his mention of Beckett’s play as a direct literary influence.

Folk Days, 1977-79: Songs from the Wood, Heavy Horses, Stormwatch

The three final Tull albums of the ’70s are, in a sense, their own world, both in their musical style of “folk rock” as significantly distinct from the already-diverse Tull sounds before them, and as, for many, the apex of “classic Tull.” Songs from the Wood can also be added to the Venn diagram: I have never heard or read about it being considered a concept album, but the album bears great unity in lyrics and music. It is also delightfully optimistic, containing very little cynicism, satire, or even sorrow. Anderson had moved to the countryside during the band’s long hiatus from touring after throat surgery, which clearly influenced the content of this album, but more importantly here, Tull’s new manager, Jo Lustig, gave “a gift to Ian Anderson of a 1973 book titled ‘Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain,’ a collection of stories and essays about ancient superstitions, festivals, places, and creatures.” Anderson says of this book,

When I read it it certainly gave me thoughts about the elements of characters and stories that played out in my songwriting for the Songs From the Wood [sic] album, which then carried on over to the Heavy Horses album, and even beyond that into the Stormwatch album. It wasn’t the only reference I had, it was just something new for me to learn from. Other than a smattering of knowledge from history lessons or hearsay I didn’t really have a definitive literary guide to that world until Jo gave me this book.

That book taught Anderson about Jack-in-the-Green, but other songs, such as “Cup of Wonder,” feature “a lot of historical and pagan references here, resulting from my delving into our history as an island nation, the forces of religion and primitive beliefs, and so on.” Anderson, unfortunately, does not list the specific sources of those historical and pagan references.

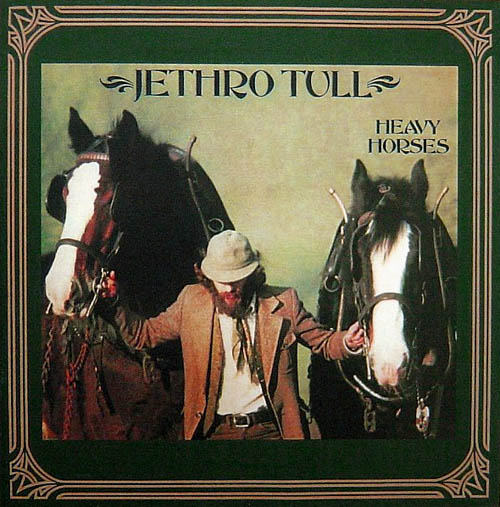

Heavy Horses is a very natural follow-up to Songs from the Wood (at its release Anderson referred to it as “Songs from the Wood, Part II, plus a little more Jethro Tull”), though it is also noticeably distinct. Nollen distinguishes them: “Songs from the Wood can be situated primarily within an English Elizabethan influence, Heavy Horses borrows more from 18th-century Scottish music.” It is also darker, with Stormwatch the darkest (and saddest) of the trilogy. The eponymous track is a superlative return, in more concise form, to the multi-movement suite so characteristic of Prog Rock (a label, we should admit, Jethro Tull abjured), though it does embody the album’s darker tone, with the days of the plow horse dwindling with the advent of the tractor. In fact, animal themes dominate the lyrics. The bonus tracks on the 40th anniversary release show this could have been an excellent double album, as most of the associated recordings could fit the album perfectly, along with most of the bonus tracks from Songs from the Wood. At least we have them now.

For our purposes, we also have a long-awaited jackpot of literary influences on Anderson’s lyrics. “Moths,” says Anderson, “was actually inspired by the John Le Carré novel The Naive and Sentimental Lover. I’m a big fan of John Le Carré’s work.” “One Brown Mouse” was “very much inspired by the Robert Burns poem ‘To A Mouse.’” While we should likely stop while we are clearly ahead, Anderson does speculate that “Heavy Horses” may also have had literary (if nonfiction) influences: “maybe I also had the Observer’s Book of Heavy Horses!” The book is actually called The Observer’s Book of Horses & Ponies, so he is either recalling a forty-year-old memory in bits and pieces, or he is making it up unintentionally, but it does have just enough truth in it to seem authentic. Similarly, bonus track “Horse-Hoeing Husbandry,” was written “as a paean to the original Jethro Tull, who in 1731 published a book called Horse-Hoeing Husbandry.” Perhaps an oblique literary influence, but it is at least a Jethro Tull song, if long dormant, written in direct response to a book and its author. Considering the band’s name was foisted upon them by an early agent and Anderson had no idea who he was at first, this track is a fine example of Anderson’s and the band’s growth, in part by willing to look backward as well as forward.

Stormwatch is the darkest of the trilogy, as we have said, both in the lyrics and in the real-life context of the album. Not only did David Palmer’s father pass away, inspiring the album’s closing number “Elegy,” but John Glascock passed away during the tour promoting the album, upon which he appears very little due to his declining health. His death cast a pall on the band, especially in the callous way Anderson broke the news to them, and things were never the same. David Palmer, John Evan, and Barrie Barlow left the band, and the ’70s and “classic Tull” came to an end, with “Elegy” becoming a poignantly fitting finale to the era. The album features mostly more mythology and Scottish rural history (“Orion,” “Dark Ages,” “Old Ghosts,” “Dun Ringill,” “Flying Dutchman”) as well as current Scottish social commentary (“North Sea Oil”), a prescient song of change (“Something’s On the Move”), a rare beautiful and uncynical Anderson song (“Home”), and the first two instrumental numbers on a Tull album since This Was (“Warm Sporran” and “Elegy”). Lyrically, aside from the general mythology and history influencing the songs, and album candidate cut for time “Kelpie,” Stormwatch is not significantly influenced by literature.

Bibliography

Anderson, Ian. “He Brewed a Song of Love and Hatred (and of quite a few other things too …).” Interviewer Martin Webb. Minstrel in the Gallery: 40th Anniversary: La Grande Édition. Chrysalis, 2015.

—. “I’ll Sing You No Lullabye.” Interviewer Martin Webb. Heavy Horses: New Shoes Edition. Parlophone Records, 2018.

—. “Kitchen Prose and Gutter Rhymes.” Interviewer Martin Webb. Songs from the Wood: 40th Anniversary Edition: The Country Set. Parlophone Records, 2017.

—. “May You Find Sweet Inspiration….” Too Old to Rock‘N’Roll: Too Young to Die! Chrysalis, 2015.

—. “To Cry You a Song.” Interviewer Martin Webb. Benefit: The 50th Anniversary Enhanced Edition. Chrysalis, 2021.

Cornick, Glenn. “To Cry You a Song.” Interviewer Martin Webb. Benefit: The 50th Anniversary Enhanced Edition. Chrysalis, 2021.

Nollen, Scott Allen. Jethro Tull: A History of the Band, 1968-2001. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002.

Thick as a Brick: 40th Anniversary Set. Liner notes. Parlophone Records, 2012.

Webb, Martin. “And the Stormwatch Brews….” Stormwatch: The 40th Anniversary Force 10 Edition. Parlophone Records, 2019.—. “Let Me Bring You….” Songs from the Wood: 40th Anniversary Edition: The Country Set. Parlophone Records, 2017.