Alice Minium

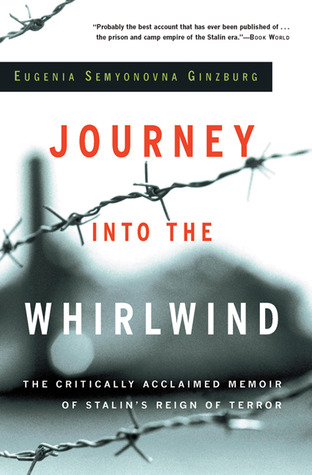

The following from alumna and Redeeming Pandora founding contributor Alice Minium (Class of 2011) is an essay on Journey Into the Whirlwind by Eugenia Ginzburg.

The trait which marked Ginzburg for persecution and the trait which allowed her the resilience to endure it were ultimately the same quality. In a state of total terror, where no one is safe from scrutiny or unfounded punishment, everyone is in danger — but none more so than intellectuals. Terror is inherently a mechanism of absolute unilateral control, not just of government, but of even the individual’s worldview. Nothing has the ability to construct belief systems or alter perception more than literature and art. Ginzburg was a prominent figure in the intellectual and artistic community, and she carried that power. It was that which would ultimately make her dangerous in the eyes of Stalin, and that which would ultimately give her strength enough to survive.

Stalin understood economic control and political control were the same. He strove tirelessly to institute the powerful, unquestionable, complete implementation of socialism. This meant not only in government and economy, but even in the very words we speak to each other and the books we read. Only through conquering the mind and fully allowing socialism to permeate one’s worldview and underlying preconceptions could the true socialist society be born. The most critical battle was fought not with laws but with ideas. Anyone wielding the power to elucidate ideas was, in Stalin’s eyes, the most dangerous soldier of all.

Suspicion against the intelligentsia predates Stalin’s terror, though he most definitely extrapolated from these preconceptions and integrated them into his framework for how to best implement his objective of total control. In The Cultural Front, Sheila Fitzpatrick describes the Old Bolshevik distrust of the academic and artistic community. In those times, things were seen almost entirely through the archetypes of oppressor and oppressed, conspirator and ally, bourgeois and proletariat. Fitzpatrick describes this thinking as one of “binary opposition,” and she quotes Lenin’s famous question, “Kto kogo?” which translates as, “Who will beat who?” Such was the lens through which all social problems and political relationships were seen.

The Old Bolsheviks were suspicious of the intelligentsia because they considered them to be too elite and reminiscent of old bourgeois ways to be in favor of the people. Intellectuals, artists, writers, and thinkers were primary political players during this time, and they overthrew norms and set the framework for new ways of life. These people were, fundamentally, free-minded and unpredictable. Ultimately, as Fitzpatrick puts it, “The Bolshevik Party and the intelligentsia shared an idea of culture as something that (like revolution) an enlightened minority brought to the masses in order to uplift them.” Culture was where wars were won and lost. Culture was the axis upon which the fragile vane of power would shift.

Stalin understood this better than anyone, and the regulation of ideas and art was equally if not more important than his regulation of the economy. Not only must he reconstruct the system, he must recreate the man. He must recreate the very identity of self.

He set about to do so with the same rapid ferocity with which he laid down economic quotas and stringent laws so inflexible efficiency was the primary goal. It was always about the most effective way to totally and completely transform, produce, or control. He illustrated this ruthlessness with his implementation of collectivization, rapid industry-building, impossibly strict regulations, and zero tolerance for economic deviance. He fiercely worked toward realizing socialism by the reconstruction and rebuilding of the systems within Soviet Russia, striving to eliminate anything left of the “old ways,” or anything that might get in the way of absolutely realizing that goal.

Since all things economic are also political, and political weight is the locus for economic power, in order to truly regulate Russia into a socialist utopia once and for all, he had to regulate the political too. Thus, with that same iron fist of efficiency, he began to zealously eradicate the most dangerous of players in the political and social game — the thinkers.

Like tsarist rituals were ruthlessly exterminated, so were those who bore capacity to express and create original notions. The ability to produce new ideas was, to Stalin, also a relic of the oppressive past, and a danger to social order, for what new ideas need there be when we have already found the ultimate idea of socialism? We have no need for ideological critique anymore — that is a relic of times past.

The idea of culture as the tool of an enlightened minority was one Stalin shared with the Old Bolsheviks and intelligentsia, yet he interpreted this idea into policy in an entirely different way. Culture was where ideas were born, and since socialism was the one and only true idea, all of culture should be mandated and consolidated into the Stalinist sphere — all ideas must come through it, and they must not be born elsewhere. In order to embody the socialist goal of Stalinism, humans must operate as appendages of the state, or as elements belonging to and defined by the greater entity of the state, functioning and thinking and producing only for its benefit. There was no place for independent ideas here. Even if a citizen was driven by true party loyalty, and expressed ideas in alignment with the goals of the party, these people were inherently dangerous because of their ability to produce ideas at all. To erase the old ways, we must erase the very idea of the intellectual. Ginzburg, a poet and respected academic, had the misfortune of being exactly that.

The overzealousness of the Great Purges was not born out of cruelty, but out of an importance on efficiency. Everyone, especially high-ranking Party officials and members of the intelligentsia, were condemned without trial or even legitimate cause and thrust into horrifically inhumane conditions. Ginzburg herself was a prominently loyal Party member who was arrested for her former association with a man who wrote a book in accordance with socialist policy at the time, but then later, when policy changed, became treasonous taboo. She was accused of belonging to a terrorist organization that never even existed, and she was tortured, deprived of sleep and food, made to suffer inhumane sanitary conditions, and threatened with her very life if she did not sign her confession to the falsified charges. Ginzburg was outraged, insisting there must be some mistake. Her every human right was being violated, and what they were doing was illegal. This was a reaction shared by many — that such an absurd norm must be some dystopian dream, because it could not possibly make sense. What changed was the law was no longer an external entity of inflexible precepts for maintaining social order — the law was Stalin, and his law was carved out in fear. The cult-like worship of Stalin’s image and the concept of total and absolute control manifested through his Terror bore ironic similarity to the monarchies of old that based absolute authority in the divine right of kings. It had ironically become that which it had sought to replace.

In a 1990 essay in “The Soviet Mind,” Isaiah Berlin writes of the incredible survival of the Russian intelligentsia against all odds. Though his essay refers to the fall of the U.S.S.R., the beautiful truth of that survival remains the same whether it is 1991 or 1939. There is a resilience to the thinker, and an indestructible fluidity to the consciousness of the artist. To be a thinker, an artist, or a scientist, one is always observing, learning, perceiving each sensory experience to its absolute fullest. To an artist, your art is only refined by suffering, and your consciousness is only expanded. Ginzburg never stopped writing, speaking, or thinking in poetry, not ever. She made no universal assumptions about her purpose being defined by circumstance — since her hope is drawn from an internal fount, not an external one, she cannot be deprived of it, and she emerges not only with her identity intact, but also far stronger than she ever was before. Ginzburg survived because of the nature of who she was. As an intellectual, her animus was fueled by suffering. It was food for her art. Her intrinsic gift of perception and a creative mind, which she never ceased to use to their fullest, enabled her to continue living even in a world of the half-death. Even this suffering was food for her soul and enrichment of her experience, and they did not impair but empowered her gift of poetry. She never ceased doing what she did best, not for a minute, because she was an artist, and artists are by nature indestructible for the nature of their craft is lovingly shattering destruction and then intimately, meaningfully weaving each experience back together in a new way, to dissect an organism and carefully reconstruct it as mosaic so it is fundamentally the same yet utterly new, and we know it so much better in an entirely new way. It is not a skill. It is a way of experiencing life. Suffering creates artists. It does not kill them.

The thread of lifeblood to which Ginzburg clings consistently throughout the book is poetry. In times of peril it calms her, in times of despair it inspires her, and in times of bliss it exalts with her. Through everything she witnesses, poetry is her life’s ever-present companion. She reflects at one point her son had once asked her: “‘Mother, what’s the fiercest of all animals?’ Fool that I was!” she cries. “Why didn’t I tell him the ‘fiercest’ was man — of all animals the one to beware the most.”

Ginzburg becomes intimately acquainted with the cruelest, fiercest most profane side of animalistic man. Yet despite our bloodthirsty animal nature, Ginzburg herself exemplifies how very much we stand apart, and humans possess something brute beasts do not. We possess poetry. We possess spirit. Ginzburg, amidst moment of utter terror and suffering, reflects upon and shares with us a story by Saint-Exupery, quoting the words spoken by a pilot lost in a wild storm at sea: “I swear that no animal could have endured what I did.”

No animal did, and no animal ever could. It is easy to look at Stalinist Terror and see the brutish error of our ways and conclude we are animals in nature, but I feel like Journey proves the opposite. You can erase regimes. You can destroy literature. You can censor every word, laugh, movement, and thought. You can strip a human of food, of safety, of family, of dignity, of pleasure for pleasure’s sake, of even her very name itself. You can erase the idea of an intellectual. You can erase the creations of an artist. You can erase the entire memory of a people.

You cannot erase their soul.

Works Cited

Berlin, Isaiah. The Soviet Mind. Harrisonburg: Brookings, 1949. 115-131.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Cultural Front: Power and Culture in Revolutionary Russia. New York: Cornell University, 1992. 1-4.

Ginzburg, Eugenia. Journey into the Whirlwind. Harcourt: Milan, 1967. 118, 358-9.

Shukman, Harold. Redefining Stalinism (Totalitarianism Movements and Political Religions). London: Routledge, 2003. 19-39.