Chris Christian

Introduction

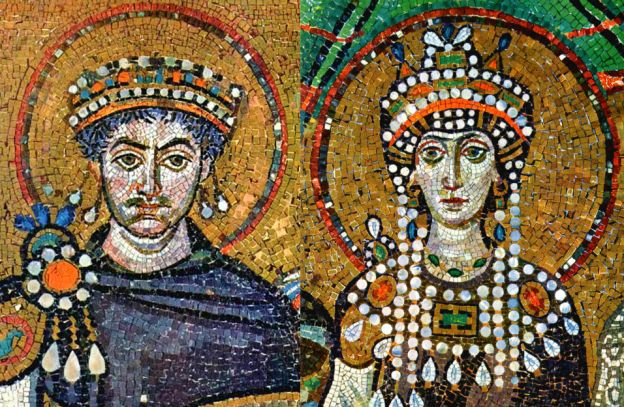

Justinian was the last Roman emperor to sit on a Roman throne. Justinian spoke Latin, just as his uncle Justin had, and thought like a Roman thought. Throughout his reign Justinian attempted to restore Rome and Byzantium to their former glory under the auspices of the glory of Ancient Rome, and used his inherited Empire of Byzantium to attempt that restoration. Justinian desired to restore to the Empire the idea of the Empire as it was before, and had not been seen since Constantine the Great. Justinian wanted his Empire to be thoroughly Christian, retaining only the glory of the former pagan Rome. Justinian wanted to incorporate the east and the west in terms of territory, faith, and law. Justinian wanted his Empire to look and feel Roman, and the restoration of that look and feel could only happen with uniformity of Byzantine architecture. There was already a Byzantine style, but Justinian would spread it throughout the Empire in a building campaign the like of which had not yet been seen.

To accomplish his ambitions, Justinian had to be a capable manager and administrator of his Empire. Justinian perhaps best earns his title Justinian the Great because of his managerial capabilities. Justinian possessed a talent for surrounding himself with people who could accomplish want he wanted them to accomplish. It did not necessarily matter if they possessed character or acted with proper discretion, so long as they got the job done efficiently and to his specifications. This work is dedicated to presenting Justinian’s accomplishments along with those of his Empress Theodora in light of their talents as managers and administrators. The best way to deal with such a topic is to focus on Justinian and Theodora’s personal and domestic accomplishments, what great things they were able to do for the people of their Empire, who they used to implement them, and how they accomplished what they were able to accomplish.

Justinian Ascends the Throne

Justinian, also known as Justinian the Great, ascended the throne after his uncle Justin’s death in 527 A.D. Justin had immigrated to Constantinople from Thrace, a peasant who rose through the ranks of the army to become commander over the Excubitors, or palace guards for the emperor. When the emperor Anastasius died in 518 A.D. Justin had acquired his position in the Excubitors, and his soldiers backed him up when his name was put forward for the throne by the Senate.1 When Justin died, Justinian acquired the throne and would later incorporate his wife Theodora as joint ruler and Empress as well. Justinian presided over his empire as a capable manager. He was not a military genius. Nor was he necessarily a tyrant. Justinian was a manager who delegated tasks, and oversaw their completion in accordance to his vision of what a Roman Empire should look and feel like.

Later Roman Government

All the government of the Empire was conducted from Constantinople, a city it seems, that was made for this one unique purpose: to govern an empire. The bureaucracy was the major employer in the city, and its offices were open to all different ranks in society by selection of the emperor. There were 5,500 guards for the palace, these being known as the Scholares, but they were more for show than actual defense of the emperor. The task of defense was left mainly to the Excubitors who were much better trained. The commander of the emperor’s bodyguard, his secret police forces, and ordinance factories was the Magister Officiorum (Master of Offices). This was perhaps the most powerful office in the palatial service. There was also the Quaestor Sacri Cubiculi (Minister for Legislation and Propaganda) who drafted legislation and approved it. The three individuals who made up the Comes Sacrarum Largitionum (Count of The Sacred Largesses) were responsible for imperial finances and the Comes Rerum Privatarum (Count of the Private Fortune) looked after the imperial revenue derived from the imperial possessions.2

The Provincial System

The provincial system divided the Empire into various provinces, each presided over by civilian and military officials. Most of these provinces were small and were governed by praeses (governors) who made certain taxes were collected and the judiciaries dispensed justice in accordance with Roman law. All of the provinces were grouped into dioceses headed by vicars and then these dioceses were grouped into prefectures each with a praetorian prefect over them.

Justinian would do away with the dioceses but retain the prefectures. Prefectures oversaw the collection of taxes in kind, or goods and produce, and set quotas for the agrarian economies present in each prefecture.3 Cities, towns, and villages in this system were taxed by a pargarch, usually an official who was held responsible for the taxes he was supposed to collect, but some towns and villages, those overseen or owned by nobles, small free landowners, or nobles who were patrons of coloni (serfs) had the right to collect taxes on their own and send them directly to Constantinople, and not through the middleman form of the pargarch.4 This meant the landowners could collect taxes for themselves, and send the requisite quota required to the capital without being answerable to a pargarch.

The military affairs for each province were overseen by a dux (duke) who had command over the troops allocated to each province. The dux was not answerable to the praeses; the two offices were now separate by Justinian’s time. The dux was a military office and the office of the praeses was a purely civilian office.5

The Army

Justinian used the army to attempt to restore former Roman territory to Byzantium. Justinian waged a series of offensive and defensive wars designed to wrest back former Roman lands and provinces and return them to their proper fold within a Roman Empire. Justinian’s wars did achieve part of these aims. Justinian would recover vast portions of former Roman territory both east and west of Constantinople. Justinian doubled the territory of the empire, recovering most of Italy, what is now modern day Algeria and Tunis in North Africa, and the southeastern portion of what is now Spain. Justinian also recovered Dalmatia, Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, and the Balearic Islands. Justinian was not able to conquer the western half of North Africa, what is now France, formally the Roman province of Gaul, and the territory north of the Alps, nor did he recover the Pyrenean peninsula.6 Although Justinian achieved much of his territorial goals, his wars left the Empire with major problems. The amount of territory was simply too vast to keep firmly under Byzantine control. The wars had been costly as well, draining much of the treasury that had been collected by previous emperors, including his uncle Justin and the emperor before Justin, Anastasius. The army would be sacrificed fiscally to make other economic ends meet and to lift the oppressive tax burden off of the population of the Empire.7 Justinian’s plans with his Empire’s army just weren’t realistic in consideration of the resources at his disposal. To his credit, it should seem amazing he accomplished what he accomplished at all. Justinian spread the existing army too thinly over his newly-conquered territories, and this thin spread of the army across the Empire made it difficult to police and control all of the newly-won territory. It has been estimated Justinian had around 150,000 men to begin with in the imperial army. It has been further estimated as the wars went on, this force would have been gradually decreased by about 25 percent throughout Justinian’s reign.8 Even with such a modest attrition rate, that would leave very few troops assigned to all of the newly-conquered portions of the Empire.

As time progressed, the army would reduce in number for various reasons. In 531 A.D. Justinian allowed slaves to join the army, which was usually only allowed during times of crisis. This could indicate a shortage of what was normally available in terms of manpower. Plague also broke out in the empire in 542 A.D., which further reduced the numbers of available manpower. Justinian began to rely on foreigners to make up the holes in the ranks of his Empire’s armed forces.9 According to Teall’s article about the barbarians enrolled in the ranks of Justinian’s army there were numerous foreigners of diverse ethnic backgrounds. The commanders Sittas, Mundus, and Chilbudius were all of foreign origins, and along with them there came to the army troops and commanders from Armenia, Slavic troops from Slavic lands and Goths and Franks who would join the previously-mentioned foreign commanders’ forces and the Armenians who had come before the wars of restoration.10 Essentially there were people from all over the Empire, and from outside the Empire, even from among the Empire’s enemies, that would come to fight for Justinian, especially during his wars of restoration. There were Armenians, Slavs, Romans, Greeks, Goths and Franks, and even Iberians. The army of Justinian would become diverse because of the shortage of manpower necessary to control his expanded Empire.

The Church

Throughout western civilization’s history the church has greatly influenced politics, even as throughout the world’s history, religion in general has influenced or asserted its dominance over affairs in politics. During his reign, Justinian assumed the responsibility of being head of the Empire’s Church and used his position as a divinely-appointed emperor to justify his dabbling in Church affairs. In other words, Justinian exerted his dominance over the Church and not the other way around. As Ostrogorsky asserts in his history, “Justinian was the last Roman Emperor to occupy the Byzantine throne. He was at the same time a Christian ruler filled with the consciousness of the Divine source of his imperial authority. His strivings towards the achievement of a universal Empire were based on Christian, as well as Roman, conceptions.”11 Justinian was certainly aware of his divine authority, especially as head of the church. Justinian even used his authority to purge the Empire of pagan teaching, practices, and ideology. “No ruler since Theodosius the Great had made such an effort to convert the Empire and to root out paganism. Though numerically the pagans were not strong at this time, they still had considerable influence in learning and culture. Justinian therefore deprived them of the right to teach, and in 529 he closed the Academy in Athens, the centre of pagan Neoplatonism.”12 Justinian’s power over Church affairs was unsurpassed, and no wonder, for it seemed from his actions to the Academy he was the Church’s greatest champion. Justinian would also be seen as its greatest secular master. “In Justinian the Christian Church found a master as well as protector, for though Christian, he remained Roman to whom the conception of any autonomy in the religious sphere was entirely alien. Popes and Patriarchs were regarded and treated as his servants.”13 Justinian’s dabbling in Church affairs knew few bounds. A great deal of the affairs concerning the Church were ultimately decided by him. Ostrogorsky claims:

He [Justinian] directed the affairs of the Church as he did those of the State, and took a personal interest in details of ecclesiastical organization. Even in matters of belief and ritual the final decision rested with him, and he summoned church councils, wrote theological treatises and composed church hymns. In the history of the relations between Church and State, the age of Justinian is the high-watermark of imperial influence in religious matters, and no other Emperor either before or after had such unlimited authority over the Church.14

Justinian’s piety was such he even quelled popular secular doctrine of his day. The philosophy, ideas, and thinking of the pagan Greek scholars were still taught in Athens at the Academy. Justinian banned such teaching. John Malalas, in his chronicle, recounts Justinian’s special decree, which would obviously have benefited the church, as it would stem the flow of any opposing secular ideals or thought from being spread throughout the Empire, especially any leftover pagan philosophy. As Malalas accounts: “… the emperor [Justinian] issued a decree and sent it to Athens ordering that no-one should teach philosophy nor interpret the laws;….”15 Watts, in his article discussing this closing, asserts Malalas is here specifically referencing the closing of the Academy, although it should be noted in Malalas’ account of the edict to Athens, no specific Academy is mentioned at all. Watts asserts all other primary accounts and sources to date do not reference the event of the Academy’s closing at all.16

The closing of the Academy in Athens is important because it shows how far Justinian was willing to go in order to promote the Church of which he was undoubtedly the head. The Academy itself was a scholarly community that thrived on the teaching of pagan Greek philosophy. It was founded in the late fourth century by a politician named Plutarch and then taken over by Syrianus and then Proclus, all high-standing citizens of Athens with ties to powerful pagans in Athens’s local government. The Academy attracted students from all over the Empire. To keep the Academy safe from growing Christian influence and potential opposition, the heads of the Academy kept their powerful political ties with their pagan patrons, but these eventually died off or converted themselves under increasing Christian pressure. The support for the Academy had begun to wan by the time Justinian came to the throne.17

By this time the Academy had adopted the teachings of Damascius, the head of the Academy responsible for the Academy’s new approach to Neoplatonic philosophy, which ran counter to the teachings of Hegia, a previous head of the Academy. Damascius replaced the older philosophy with newer teaching. This newer teaching was still inspired by the ancient Greek fathers of philosophy Aristotle and Plato. This new teaching was the foundation of Neoplatonic thought.18 By banning such pagan-influenced teaching within the empire, Justinian would have found greater support from the Church, or at the very least he could have pointed to the edict as evidence of his championship of the Church.

Justinian also waded in the mire of Christological disagreements that plagued the present Empire. The essential disagreement among Church clergy in the Empire concerned the nature of Christ. Ostrogorsky best summarizes this disagreement, simplifying its complexity for those not familiar with arguments concerning Church doctrine of the time or disagreements about such doctrine among the faithful of the time.

In response to the challenge of Arianism the Church formulated the doctrine of the complete Godhead of the Son and His consubstantiality with the Father; the question now at issue was the relation of the divine and human natures in Christ. The theological school of Antioch taught that there were two separate natures coexistent in Christ. The chosen vessel of the Godhead was Christ, the man born of Mary….19

This view was one side of the disagreement, but was opposed by those known as Monophysites. The followers of this sect, whose teachings hailed from Alexandria, taught that Christ’s natures, both human and divine, were united constantly.20 In 451 A.D., at the Council of Chalcedon, a special Church council called to meet the Monophysite doctrinal challenge, the council set the new tone for doctrine on the nature of Christ for the Empire. The council “formulated the doctrine of the two perfect and indivisible, but separate, natures of Christ. It condemned both the Monophysites and the Nestorians. Its own dogma stood as it were midway between the two; salvation came through a savior [sic] who was at the same time Perfect God and perfect man.”21

Despite the decision at the Council of Chalcedon, Monophysite influence still spread throughout the eastern portions of the Empire. Later on, after the council, the tension between the two came to a head as a void began to grow between the western and eastern halves of the Empire over the issue. In 482, emperor Zeno published the Henoticon (Edict of Union) in an attempt to find a compromise between the two sides regarding the dual nature of Christ. Zeno set out to forge the compromise by avoiding the numerical terminology of either one or two concerning the term “nature.”22 This ad hoc compromise did little to heal the rift between the spiritually-divided Empire.

By the time Justinian was overseeing imperial affairs under his uncle Justin, Justinian found himself facing a serious problem. The Monosophyte sect had essentially blanketed the eastern part of the Empire and held the powerful ecclesiastical cities of Alexandria and Antioch under its influence. Only Palestine proper, and Constantinople, the meeting place of the Chalcedonian council and capital of the Empire, were Chalcedonian in outlook. These seats of Chalcedonian thought were also not enough to sway any help from Rome proper, whose Pope and clergy did not view the Church of Constantinople as being doctrinally sound simply due to their acceptance of the compromise edict issued by Zeno.23

The problem of unifying the faithful under Chalcedonian belief in Christ’s dual nature was important for Justinian for two reasons, the first was he himself supported the Chalcedonian view and the second was in order for his conquest of Italy to succeed, it would be helpful for Justinian if his Empire were Chalcedonian in the belief concerning Christ’s dual nature, just as the Church in Rome was Chalcedonian in belief regarding Christ’s dual nature. Justinian actively sought for a means to reconcile the Christian sects within his Empire: Chalcedonians, Monophysites, and the Roman Catholics in Italy after its conquest.24 Justinian forced the current patriarch of the Orthodox Church in Constantinople to accept his attempts at unity with the papacy in Rome. Justinian issued an edict in 543 A.D. that specified the patriarchs’ position within the empire as being second to the pope in Rome, and there were to be five patriarchs who would oversee the affairs of the church, but all of these would be answerable to the Emperor. Justinian faced opposition for his edict from the clergy and laymen of each sect, which created trouble for Justinian in the long run.

Justinian believed his authority as a divinely-appointed emperor gave him the necessary power to unite the faithful and different sects under himself. Justinian believed he was the head of the Church, then Rome, then the Patriarch of Constantinople, and then the other three patriarchs in their proscribed order as laid out in the edict.25 It is interesting to note even with this ordering system, Justinian still had Constantinople at the top of the religious ranking system.

Justinian had to make himself head of the Church in order to meet his ambitious goals, unification of the faithful, and the successful conquest of Roman Catholic Italy. This move helped with the problem of Roman acknowledgement of the Orthodox Church’s Chalcedonian views, but what of the Monophysites? Justinian could change the leadership positions of the Church, but he could not directly force changes in doctrine. Justinian acknowledges this by encouraging discussion among Chalcedonian groups to come to a compromise, one that would satisfy dissension within their ranks and provide a rebuttal to Monophysite assertions about Christ’s dual nature. Meyendorff in his article about Justinian’s relationship with the Church describes the dilemma:

Justinian himself and his theological advisers soon understood that the Monophysite criticisms would not be met with either negative or authoritarian answers alone. They became painfully aware of the fact that Chalcedon, as an independent formula, was not a final solution of the pending Christological issue: that its meaning depended on interpretation. They had to have recourse to constructive interpretations of Chalcedon….26

Justinian and his theologians encouraged theologians to come up with varying interpretations of Chalcedonian precepts to answer Monophysite arguments and hopefully influence some, if not all, to accept some form of Chalcedonian belief concerning Christ’s dual nature.

This compromising over doctrine and reinterpretation of doctrine ended up posing more problems for Justinian with the Roman Catholic Church in the West, whose leadership were not happy with Justinian’s policy of compromise with the Monophysites, nor with his attempts to persuade them to accept Chalcedonian beliefs by leaving them open to interpretation. Justinian would have to resort to force. Justinian responded to the Western Church by attempting to replace the Pope with the former Orthodox Patriarch Vigilius, which was resisted vehemently for six years until the West gave in and recognized Vigilius as Pope.27

As Ostrogorsky asserted, Justinian exercised authority over the Church like few other secular rulers in history ever would. Justinian found it necessary to do so in order to meet his ambitious aims and solve problems he saw as potentially devastating to his concept of what the Empire should be. Justinian used force, reinterpretation of doctrine, edicts, and Church councils in order to meet his ends, to manipulate the Church in order to manipulate the people.

Justinian’s Court

To be as effective a manager as Justinian was, he needed to have surrounded himself with capable people who could carry out his projects and tasks. Justinian’s ambition knew few bounds, and it was for this reason the people who made up his court and were his councilors had to be reliable individuals who could get things done.

Justinian seems to have relied on three key individuals in order to get things accomplished. One of these was John of Cappadocia, an interesting individual whom Justinian relied upon to bolster the treasury. Justinian relied upon John for financial support for his broad projects and he served as Justinian’s finance minister.28 Barker paints a simple yet complete picture of the man: “John was at the very least, a vivid personality: of great physical strength, he was also bold, outspoken, shrewd, endlessly resourceful; but unscrupulous, cruel, ruthless, sadistic, depraved and insatiably greedy. Nevertheless, these qualities were subordinate, or contributory, to the one essential virtue which commended him most to Justinian; he could raise money.”29

Justinian also seems to have relied upon John to head various projects, even placing him in charge of the first committee tasked to recode the law. John drove the committee to complete the massive project in under a year. The project had been implemented just seven months after Justinian’s uncle Justin’s death.30

Another member of Justinian’s court who proved both useful and influential would have to have been Tribonian. Tribonian, a lawyer by training, served the emperor with respect to Justinian’s legal projects. Justinian made Tribonian Quaestor, the top position within the Empire’s judicial system. As Barker asserts in his history, Tribonian was shrewd, highly educated and therefore seemed to have been an excellent choice for such a position.31 Justinian assigned Tribonian the task of codifying the law a second time, after John’s attempt at codification. In the twenty months since the first codification, Justinian had purged all of the pagans from among his bureaucracy. Justinian wanted Tribonian to condense the previous codification and court records into a more tangible form, which could be readily applicable by the Christian judicial bureaucracy that remained.32 Tribonian is the man largely responsible for the product of this commission.

The last member of the court to be considered would have to be Peter Basymes. Peter was a favorite of Justinian’s Empress Theodora. He was made a Count of the Sacred Largesses which made him a secretary for the treasury. Like John, Peter proved himself useful in the acquisition of funds, a commodity highly useful to Justinian.33

There were other individuals Justinian counted upon within his court to conduct his affairs. One important individual, often away from court due to his position and Justinian’s schemes, was Belisarius. Belisarius was the commanding general-in-the-field of Byzantium’s armies engaged in the re-conquest of former Roman territory. Barker is also capable of summarizing a picture of the man: “This is Belisarius, the outstanding general of the age, and one of the remarkable commanders of history. He was an extremely able field commander, a skillful tactician and strategist, and a capable administrator. His particular genius lay in accomplishing maximum results with minimum resources.”34

Barker further asserts that unlike Justinian’s closer courtiers, Belisarius was an upstanding man, a true Roman as it were in the stoic sense although not in an ethnic one. “Though he shared an Illyrian peasant background with Justinian, he was quite different from his master in his simple and straightforward personality. As circumstances showed, he was capable of cunning and deception, but he had the advantages of an upright character, unimpeachable morals, and unwavering loyalty.”35

All of these capable people along with others in the bureaucracy aided Justinian in fulfilling his agendas, or in the attempt of fulfilling them, for not every task undertaken by Justinian was entirely successful or beneficial to the Empire. Like any manager in any managerial setting, Justinian had the vision and the will to decide what could or should be done and then after ascertaining that vision, Justinian then delegated various tasks to others, or seek the advice of others on how to get it done. Justinian strived for unsurpassed excellence, in as efficient and timely a manner as was possible, for each project he had set about on. This aspect of his management can be seen in each aspect of his reign, his dealings with his court, his building program, and his dealings with the army and church. Justinian strove for things to be in accordance to his vision of what the Empire should be, and to be close to Justinian meant you also had to be useful to him.

Theodora

No work on Justinian can be justifiably complete without dealing with Justinian’s Empress, Theodora. Theodora came from a lowly background just like her husband Justinian. She was the daughter of an animal keeper for a circus in Constantinople, one Acacius, who having died, left behind Theodora, her mother, and two other daughters. Her mother later remarried to a certain Asterius, an employee of the same political faction as Acacius, but who had been much higher up the ranking ladder of the Greens (a political faction made up of the lower orders spawned from and often represented at the games in the Hippodrome by teams that bore their colors. The Blues were made up of and represented the nobility; the Greens the common people). Asterius became Theodora’s stepfather, and her family was under his protection throughout her childhood.36

Theodora received an education of sorts through the environment her family provided her. They worked for the circuses and theaters in Constantinople, and Theodora had access to these theatres and to the Hippodrome. She saw the Greek works, the mythologies, tragedies and comedies.37 As Cesaretti asserts:

Antiquity — the mythical, miraculous antiquity — would be revealed to her not in papyrus rolls or parchment volumes but through tales, images, and visions. She was attentive and curious enough to grasp all of this. She developed her own, unique education, more visual than verbal, through what she saw even before what she heard, on the stages of the Hippodrome, the Kynêgion, [similar to Rome’s Coliseum, used to stage hunting games or displays with large beasts as prey] and the theaters: her open, outdoor libraries.38

Theodora’s mother initiated Theodora’s career onto the stage. Theodora performed with her older sister Comito, dressed as a boy and following Comito around on stage. Both sisters were reportedly beautiful and this beauty apparently signified the acting career as one suitable for the sisters by their mother.39 As Theodora approached womanhood, she became a full-fledged actress. No longer in her sister Comito’s shadow, Theodora acted in shows in her own light but still in supportive roles. Theodora danced in shows as part of a group, but was not very adept at it, or at acting in general. Theodora was, however, exceptionally beautiful, and it was this singular beauty that made her mother decide Theodora was more conducive to the role of a courtesan, along with her inability to sing or dance, at least in proportion to her beauty.40 Theodora became, for all intents and purposes, a prostitute.

Theodora was not pleased with this career path; she sought something more stable, something that offered her protection and not exploitation. She put her beauty to work for her and managed to become the mistress of Hecebolus, an official, who took her to North Africa with him when he was appointed governor of a province there. The relationship went sour, and Theodora managed to flee from it to return to Constantinople. She stopped at Alexandria where she was introduced to the Monophysite sect of Christianity and was converted from her previous ways of life. Upon her return home she lived close to the palace and spun wool for a living.41 Although considered on the borderline of midlife at this time, Theodora must still have been exceptionally beautiful and her experiences with life, along with her previous educational experiences from the theater, provided her with all that was necessary to attract her neighbor the emperor. Browning summarizes what Theodora must have been like at the time of her acquaintanceship with Justinian: “She was still strikingly beautiful by all accounts, though her countenance bore the marks of her eventful life. Nature and experience had given her a quick and ready wit, an unfailing memory, and a talent for public appearance. Her self confidence was boundless, and she feared no man. Somewhere, somehow, she had acquired a wide, if superficial, culture….”42 Of course that culture had to have come from her introduction to theater and her life experiences among the people in the theaters and the Hippodrome. Justinian was an older man when he met Theodora, but he could offer her what no other man at that time could. By marrying Justinian, Theodora would have what she had desired: security and freedom from her past.

Justinian when he met her was about fourty, [sic] of medium height, with a rather heavy, somewhat florid face. On the surface rather a cold man, approachable but not sociable, he was a compulsive worker at state papers, with a meticulous attention to detail and a remarkable capacity for going without sleep. His ambition was boundless, his patience endless, his plans laid carefully for years ahead …. Theodora was his ideal complement. She had every social grace, she lived for the present, and she never lost her head in a crisis. He was devoted to her, and their confidence in each other was absolute.43

Browning succinctly sums up what Theodora ultimately meant to a man like Justinian. She completed Justinian, and after their marriage, and her ascension to power with him, they would be partners.

Partners in Power

Despite their being married in the day and age in which they were married, Justinian did not end up being an overlord to Theodora. Rather, their reign can be seen as a partnership. Justinian supported Theodora even when they did not see eye to eye. As has been previously touched upon Theodora was a Monophysite, and Justinian was an ardent Chalcedonian. Despite their religious differences, they cooperated and shared their power together. Theodora was an advocate of Severus, a Monophysite theologian who lived and worked in Alexandria.44 Hardy asserts Justinian and Theodora’s partnership despite their religious differences in, surprisingly, his article about Justinian’s policy towards Egypt. Hardy claims: “While Theodora’s Monophysite loyalties were genuine, and her influence not to be underestimated, it does seem that Justinian intentionally tolerated her pro-Monophysite actions, including the amusing support of a Monophysite monastery in the palace of Hormisdas, as a means of keeping in contact with a party which he could not completely suppress.”45

Theodora’s influence can also be seen in other aspects of Justinian’s management of the Empire as well, including the interesting removal of John of Cappadocia from court. Justinian highly valued John of Cappadocia’s work regarding the allocation of funds for Justinian’s projects. Unfortunately for John, Theodora hated him for his influence over Justinian and she further despised John because his fundraising methods were destructive to the general public.46 Theodora undertook in 541 A.D. to attempt to trick John into joining a sham conspiracy against Justinian. Theodora used political spin, intrigue, and deception to convince John to commit to the fake conspiracy and to get others to believe he was involved. Justinian reluctantly agreed to exile John, and during that exile Theodora pursued him with her agents, seeking his death in order to assuage her hatred. John was summoned from exile after Theodora’s death in 548 A.D. but he would hold no position of power.47 This might possibly have been due to Justinian’s respect for his deceased wife, and partly to the possibility John, having been a marked man by the Empress was not to be trusted in political circles.

Procopius

It is necessary here to discuss Procopius, an invaluable source for scholars working with Justinian who also happened to be a member of Justinian’s court, in that he was General Belisarius’ secretary. Procopius first appeared in written history when Justinian mounted the throne in 527 A.D. and left it around 560 A.D.48 It is necessary to discuss Procopius because he is one of the few exhaustive sources for the period of Justinian’s reign. It is also necessary because Procopius’ works, especially The Anectdota, may need to be taken with a grain of salt, or are exaggerated in their accounts. Evans seems to support this in his short work on Procopius, saying it seems paranoid in nature and Procopius’ treatment of Theodora does not match treatment of her by Byzantine tradition.49 Evans also claims Procopius might have written the scandalous things about Theodora written in The Anectdota in order to “titillate his readers.”50 Cameron’s work on Procopius also comes to a similar conclusion regarding his writings about Theodora. Cameron claims Procopius was suspicious of women in power, and he bore hostility toward Theodora because she gave protection to women under Byzantine law.51 It is for these reasons Procopius’ accounts in his Anectdota should be met with some skepticism, especially as they regard Theodora.

The Nika Riot

The Nika Riot of 532 A.D. is crucially important in consideration of Justinian’s management for several reasons: first, it demonstrates near failure in his management; second, as the riot progresses to its shocking conclusion, it shows Justinian as a triumphant victor as the manager of his Empire; lastly, it shows how deeply Justinian and Theodora were partners in that management. One can find accounts of the Nika Riot in primary form from both John Malalas and Procopius.

Malalas’ account begins with the arrest and hanging of various members of the two main political factions represented at the races in the Hippodrome, the Blues and the Greens. Malalas’ account claims two men survived the hanging, one a Blue and the other a Green, and having been found by certain monks, were taken by these monks to St. Lawrence, a church that offered sanctuary to those who sought it. The current prefect besieged the two men as they were kept inside the church.52 The Hippodrome held races three days after the hangings, and during the races members of both the Blues and Greens appealed to Justinian, who was present, to release the two escapees. Justinian did not answer the appeal and the two factions united temporarily in revolt, using the Greek term Nika (“conquer”) as a watch-word, to know who was for them or against them. The rioters demanded the release of the escapees, but Justinian, having refused to answer, was now faced with a full scale revolt in his capital.53 The rioters set fire to the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) and to the praetorium where the prefect worked. This fire also destroyed portions of the palace. Malalas’ account also claims the rioters called for the dismissal of John of Cappadocia and Tribonian along with the current prefect Eudaimon. They were dismissed, and Malalas’ account claims Belisarius was sent to quell the rioters. Malalas’ account claims the rioters began to kill people indiscriminately after Belisarius was dispatched to quell the riot.54 Justinian presented himself to the people at the Hippodrome and made a proclamation to them backed by an oath to follow its contents. Malalas’ account claims a portion of the rioters then claimed Justinian as their emperor, while others claimed one Hypatios, who, when Justinian had left, seated himself in the emperor’s place at the Hippodrome. Malalas’ account claims after this blatant act of rebellion, the Magistri Militum was sent to the Hippodrome to slay all who opposed Justinian, and Hypatios was put to death. Malalas claimed 35,000 people were slain in the Hippodrome.55

Procopius’ account differs from Malalas, as he includes more detail on the causes of the riot and the palatial goings on during the riot. The vital importance of Procopius’ account is he includes Theodora’s role during the revolt, and her influence over Justinian is credited by Procopius for Justinian’s confrontation of the people as accounted for by Malalas. Procopius’ account of the riot claims Justinian contemplated fleeing from Constantinople by sea, but Theodora convinced him to stay and confront the people.56 Theodora delivers a speech to stir her husband and partner in power to confront the people. Her speech is impassioned, and in it she acknowledges she does not wish to lose her position, nor does she wish for her husband to lose his. According to Procopius Theodora said in her speech:

My opinion then is that the present time, above all others is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that die on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats.57

This speech would have probably appealed to Justinian’s pride, and anyway, Procopius asserts it produced the results Theodora desired. Procopius claimed the speech placed new heart in all who heard it and they made ready to meet the challenge before them, even Justinian.58 This speech was the necessary motivation for Justinian to confront the people and meet their challenge to his authority with force.

Bury makes an interesting observation concerning the two accounts in his old yet informative article on the Nika Riot. Bury points out Malalas’ account of the riot and Procopius’ account of the riot may be different because they involve two different perspectives. Bury asserts Procopius’ account was taken from the perspective of one being inside the palace, observing what the emperor and his court heard and saw. Bury also asserts Malalas’ account came from the perspective of an eyewitness to events as they would have occurred in the streets of Constantinople.59 This would account for the differences in various aspects of their accounts of the Nika Riot. The important thing to note from the riot, however, is Justinian and Theodora chose to meet the threat in partnership. In the end 35,000 people may have died, and while this points to a failure on Justinian’s part as a manager, things could have possibly gone worse were he to have fled as he had first desired, or have allowed someone else like John of Cappadocia to take matters in their own hands.

Justinian’s Building Program

Up to this point, Emperor Justinian’s remarkable management of the empire in all of the domestic aspects dealt with by this work have been made manifest by the results the Empire received as a result of such management. Justinian has shown himself to have been a remarkable manager and administrator. Justinian selected qualified people to whom he could delegate work and it was done. The same management skills Justinian exercised with the domestic cogs and wheels of his Empire he devoted with even greater zeal to his building program.

Justinian changed Constantinople’s landscape dramatically, emptying the treasury of the empire to do so as his dealings with John of Cappadocia and his constant need of him should assert, just as effectively as his ineptly determined wars to expand the Empire did as well. Justinian built shrines and churches to saints, hospices, monuments, and numerous other public works on a massive scale. It is perhaps because of this massive public works building campaign Justinian is regarded as Justinian the Great.

Constantinople appears to have seen the greatest recipient of the huge public works building campaign Justinian waged throughout his reign. This makes perfect sense being the capital of the empire of course. According to Downey, Procopius was specially selected by Justinian to write a written record of these works. Procopius was ordered to produce an official work on the entire building program, which he must have written between 559 and 560 A.D. This work was first titled On the Buildings of the Emperor Justinian, but later copies are titled Buildings.60 The first portion of Buildings details the churches of Constantinople. The later portions discuss other edifications throughout the empire, mostly fortifications and aqueducts.

The Hagia Sophia

Perhaps Justinian’s greatest accomplishment of his building campaign was the reconstruction of the Church of Holy Wisdom, the Hagia Sophia, after its partial destruction during the Nika Riot. Procopius implies the destruction of the Church was allowed by God in order that Justinian could rebuild it more glorious than ever:

Some men of the common herd, all rubbish of the city, once rose up against the Emperor Justinian in Byzantium, when they brought about the rising called the Nika Insurrection…. And by way of showing that it was not against the Emperor alone that they had taken up arms, but no less against god himself, unholy wretches that they were, they had the hardihood to fire the Church of the Christians, which the people of Byzantium call “Sophia” an epithet which they have most appropriately invented for God by which they call his temple; and god permitted them to accomplish this impiety, foreseeing into what an object of beauty this shrine was destined to be transformed.61

Evidently Justinian thought the same, for as Procopius accounts, the church was rebuilt more grandly than before and perhaps more grandly than any other church of its time had been built.

Justinian assigned two craftsmen to design and oversee the construction of the new church. Justinian hired Anthemius of Tralles, whom Procopius describes as a highly educated man unsurpassed in the art of construction and architecture, and his associate Isidorius, another master builder and architect with great talent and expertise. Both architects delegated tasks to their workmen, and as Procopius asserts, Justinian and his two architects spared no expense on the construction of the new and improved Hagia Sophia.62

Procopius also points out Justinian’s great penchant for surrounding himself with capable and qualified people was the major reason for his success with Hagia Sophia’s reconstruction, as has been seen in other aspects of Justinian’s reign.

Indeed this also was an indication of the honour [sic] in which God held the Emperor, that He had already provided the men who would be most serviceable to him in the tasks which were waiting to be carried out. And one might with good reason marvel at the discernment of the Emperor himself, in that out of the whole world he was able to select the men who were the most suitable for the most important of his enterprises.63

This penchant, which Procopius evidently believed was God given, was to guide and prove highly resourceful for Justinian throughout the beginning of his reign. This has been evident before, but Procopius also was aware of its presence in Justinian’s management technique throughout the building program.

The Hagia Sophia is described in great detail by Procopius, from its height, its views to the city and from the city to the church, its decoration inside and out, and so forth. Procopius gives his readers a picture of the Church as it would have looked brand new. Procopius describes the church with passionate emotion, as if he were quite proud himself of Justinian’s achievement, perhaps even considering it Justinian’s greatest work. Procopius declares the impossibility on his part to do the church justice in its description:

But who could fittingly describe the galleries of the women’s side, or enumerate the many colonnades and the colonnaded aisles by means of which the church is surrounded? Or who could recount the beauty of the columns and the stones with which the church is adorned? One might imagine that he had come upon a meadow with its flowers in full bloom. For he would surely marvel at the purple of some, the green tint of others, and at those on which the crimson glows and those from whom the white flashes, and again at those at which Nature, like some painter, varies with the most contrasting colours. And whenever anyone enters this church to pray, he understands at once that it is not by any human power or skill, but by the influence of God that this work has been so finely turned.64

Procopius would match few others of Justinian’s works with such praise and impassioned description in his own works. It is the very first work accounted for in Buildings due to its importance in Procopius’ eyes, and, in terms of Justinian’s accomplishments, it was deemed necessary to likewise render Hagia Sophia’s reconstruction a prime position in this work as well.

Church of Eirenê, and the Houses of Isidorius and Arcadius

There is also the Church of Eirenê, which Justinian also rebuilt. Procopius accounts this church was also destroyed during the Nika Revolt and was rebuilt by Justinian so that it was second in the city and by default the rest of the Christian world only to the Hagia Sophia. Unfortunately Procopius says little about its appearance, other than it lay next to the Hagia Sophia.65

Justinian’s public works of a pious nature do not halt there. Justinian built large numbers of saints’ shrines and churches throughout the region around Constantinople. Two other interesting works accounted for by Procopius are the Hospices of Isidorius and Arcadius. Procopius refers to them as the House of Isidorus and the House of Arcadius, being two buildings erected by both Justinian and Theodora to serve as hospices to the people in the city of Constantinople.66 There are many other churches and shrines likewise rebuilt or built by Justinian within the capital city proper. Procopius accounts for each specifically in his account in the Buildings, including the church of St. Anna, the shrine of Pegê, the shrines of St. Sergius and Bacchus; many others are accounted for both as works by Justinian as emperor and as an administrator during the reign of his uncle Justin.67

The Bay: Justinian’s Healings

Along the shores of Constantinople, all along the shores of the three straits that divide the city from Asia to the east, north, and south of the city, Justinian built similar religious and public and private works. Procopius accounts for many of these particularly along the bay to the north of the city. It is on the shores of this bay Procopius accounts for two very interesting churches. They are interesting because both involve the healing of the emperor Justinian of serious illness or ailment.

Healing at Saints Cosmas’ and Damian’s Shrine

The first site of healing was a shrine dedicated to St. Cosmas and St. Damian. Procopius accounts Justinian lay at this shrine so ill he was taken for dead by his attendants and personal physicians. In a vision, both saints miraculously raised Justinian from his illness, and to recognize these saints for their miraculous work and as an act of faithful thankfulness, Justinian reconstructed the church holding their shrine.68

Healing at the Church of the Martyr Eirenê

Remarkable in and of itself, Procopius will also account for another healing upon the person of the emperor Justinian in the same coastal area. Justinian had reconstructed the Church of the Martyr Eirenê in this area. During excavation in the area for stone to build the church, the masons discovered the remains in a chest of forty holy men, believed to have been legionnaires who had served in Armenia in the Twelfth Legion long before. Up to this time Justinian had been suffering severe pain in his knees, for which Procopius asserts was due to weakness brought on by a harsh, self-inflicted fast Justinian was enduring during the period of fasting before Easter. When Justinian heard the relics had been found, he took it as a sign from God, that God was pleased with his church and Justinian in particular, so Justinian called for the relic to be brought to him and placed upon his knee. According to Procopius, because of Justinian’s faith in God, God caused the pain to cease immediately, and the chest overflowed with oil that soaked Justinian’s royal tunic, which was preserved to prove the event did indeed transpire and Justinian had been healed by God.69

The Convent Repentance

One of the more interesting of Justinian’s pious related public works was the Convent Repentance. Procopius claims both Justinian and Theodora set out to free the oppressed women bound to a life of prostitution by their state of destitution by setting up a convent where such women could flee, seek remission for their sinful pasts, and receive shelter within the convent. Procopius claims brothels were banned within the empire that plied the trade of prostitution, and the convent was funded and maintained by Justinian and Theodora. Any woman who came could stay, in order that she could remain free from a life supported by prostitution.70

The Palace and Senate House

Justinian also built his own palaces, and even reconstructed the entire palace area after it had been destroyed. Procopius does not give details about the palace, but states simply which portions were the works of the emperor Justinian: “this Emperor’s work includes the propylaea of the Palace and the so-called Bronze Gate as far as what is called the House of Ares, and beyond the Palace both the baths of Zeuxippus and the great colonnaded stoas and indeed everything on either side of them as far as the market-place which bears the name Constantine.”71 Procopius also asserts the entire residence of Justinian himself was completely brand new. Procopius implies its size and grandeur defy description, so he does not attempt to describe it, only its entrance. Procopius claims the entrance, called the Chalkê, is formed by arches that support its ceiling, upon which are pictures viewed from below of Justinian’s military victories won for him by his general Belisarius.72

The Basilica Cistern

Malalas’ account reports Justinian, after sacking John of Cappodocia and appointing Longinus as the new prefect in his place, also paved the central hall of the Basilica Cistern and built its colonnades in 542 A.D. Essentially Malalas’ account gives Justinian credit with either all of the construction for the Basilica or at least for its completion.73

Most of the rest of Procopius’ accounts concern fortifications built to guard the boundaries of his now far-flung Empire or aqueducts built to quench his thirsty cities. Procopius even asserts at the end of his Buildings there were many more structures Justinian was responsible for building, so much so it would be necessary for another to write of them.74

Conclusion

Justinian it would seem justifies the assertion he was indeed a capable manager, in the respect he was capable of attempting to carry out implementation of and, more often than not, completion of his vision for the Empire. This aspect of managerial talent displayed by Justinian and empress Theodora can be clearly seen through his restoration of lost Roman territory, his dealings with the Church to secure necessary religious and political ends for his vision of a unified Christian Empire, and with their joint handling of the Nika Riot, which expresses their partnership in power. Justinian’s building program alone would have required considerable managerial skills to oversee its undertaking to the scale Justinian attempted. Justinian’s military accomplishments may have been superfluous for his Empire, but his domestic accomplishments are extraordinary, especially when one considers they were all undertaken within the same period, along with the series of wars he waged. An Empire constantly at war under Justinian was still able to accomplish and build so much. It would only have been possible under managers like Justinian and Theodora.

Endnotes

1 Evans, J. A. S. The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power. New York: Routledge, 1996. 11-13.

2 Evans, J. A. S. The Emperor Justinian and the Byzantine Empire. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005. 41-42.

3 Ibid., p. 5.

4 Bell, H. I. “An Egyptian Village in the Age of Justinian,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 64, (1994): pp. 21-36. http://links.jstor.org., pp., 22-24.

5 Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 5.

6 Vasiliev, A. A. History of the Byzantine Empire, 2nd ed. vol. 1. Madison: UWP, 1964. 138.

7 Ibid., 141-142.

8 Evans, The Age of Justinian, 51.

9 Ibid., 51-52.

10 Teall, John L. “The Barbarians in Justinian’s Armies,” Speculum, 40, no. 2, (Apr., 1965): pp. 294-322. http://links.jstor.org, pp. 297-301.

11 Ostrogorsky, George. History of The Byzantine State, trans. Joan Hussey. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1957. 70.

12 Ibid., 70-71.

13 Ibid., 71.

14 Ibid.

15 Malalas, John. The Chronicle of John Malalas, ed. and trans. Elizabeth Jeffreys, Michael Jeffreys, Roger Scott, and Brian Croke. Melbourne: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies: Department of Modern Greek, University of Sydney, 1986. 264, 18:47.

16 Watts, Edward. “Justinian, Malalas, and the End of Athenian Philosophical Teaching in A.D. 529,” The Journal of Roman Studies, 94, (2004): pp. 168-182. http://links.jstor.org, p. 168.

17 Ibid., 169.

18 Ibid., 169-170.

19 Ostrogorsky, 53-54.

20 Ibid., 54.

21 Ibid., 55.

22 Ibid., 59.

23 Meyendorff, John. “Justinian, the Empire, and the Church,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 22, (1968): pp. 43-60. http://links.jstor.org, p. 47.

24 Ibid., 47-48.

25 Ibid., 47-51.

26 Ibid., 56.

27 Ibid., 57-59.

28 Barker, John W. Justinian And The Later Roman Empire. Madison: UWP. 1966. 72-73.

29 Ibid.,73.

30 Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 23.

31 Barker, 72.

32 Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 23.

33 Barker, 74-75.

34 Ibid.,75.

35 Ibid.

36 Ceasaretti, Paolo. Theodora: Empress of Byzantium, trans. Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. New York: Vendome Press, 2001. 25-41.

37 Ibid., 60-61.

38 Ibid., p. 61.

39 Ibid., 62-63.

40 Ibid., 72-73.

41 Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1987. 39-40.

42 Ibid., 40.

43 Ibid., 42-43.

44 Hardy, Edward R. “The Egyptian Policy of Justinian,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 22, (1968): pp. 21-41. http://links.jstor.org, p. 31.

45 Ibid., 31-32.

46 Barker, 74.

47 Ibid.

48 Evans, J. A. S. Procopius. New York: Twayne’s World Authors Series: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1972. 15-16.

49 Ibid., 87.

50 Ibid.

51 Cameron, Averil. Procopius: and the Sixth Century. Berkeley: U of California P, 1985. 81.

52 Malalas, 275.

53 Ibid., 275-276.

54 Ibid., 277-278.

55 Ibid., 278-280.

56 Procopius, History of the Wars, book 1. vol. 1, Procopius trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge: HUP, 1979. 231.

57 Ibid., 231-233.

58 Ibid., 233.

59 J.B. Bury, J.B. “The Nika Riot,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 17, (1897): pp. 92-119. http://links.jstor.org, pp. 93-94.

60 Downey, Glanville. Constantinople in the Age of Justinian. Norman, Oklahoma: U of Oklahoma P, 1960. 94-95.

61 Procopius, Buildings, vol.7, Procopius trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge: HUP, 1979. 11.

62 Ibid., 11-13.

63 Ibid., 13.

64 Ibid., 27.

65 Ibid., 37.

66 Ibid.

67 Ibid., 39-57.

68 Ibid., 63.

69 Ibid., 65-69.

70 Ibid., 75-77.

71 Ibid., 81.

72 Ibid., 83-87.

73 Malalas, 286.

74 Procopius, 393.

Bibliography

Agathias. The Histories. vol. 2. Trans. Joseph D. New York: Walter De Gruyter Press, 1975.

Barker, John W. Justinian And The Later Roman Empire. Madison: UWP. 1966.

Bell, H. I. “An Egyptian Village in the Age of Justinian.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 64, (1994): pp. 21-36. http://links.jstor.org.

Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1987.

Bury, J.B. “The Nika Riot.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 17, (1897): pp. 92-119. http://links.jstor.org.

Byron, Robert. The Byzantine Achievement: An Historical Perspective, A.D. 330-1453. New York: Russell & Russell Inc., 1964.

Cameron, Averil. Procopius: and the Sixth Century. Berkeley: U of California P, 1985.

Ceasaretti, Paolo. Theodora: Empress of Byzantium. Trans. Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. New York: Vendome Press, 2001.

Downey, Glanville. Constantinople in the Age of Justinian. Norman, Oklahoma: U of Oklahoma P, 1960.

Evans, J. A. S. “Justinian and the Historian Procopius.” Greece and Rome, 2nd Ser., 17, no. 2 (Oct., 1970): pp. 218-223. http://links.jstor.org.

—. Procopius. Twayne’s World Author’s Series. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1972.

—. The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power. New York: Routledge, 1996.

—. The Emperor Justinian and The Byzantine Empire. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Hardy, Edward R. “The Egyptian Policy of Justinian.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 22, (1968): pp. 21-41. http://links.jstor.org.

Honoré, A. M. “Some Constitutions Composed by Justinian.” The Journal of Roman Studies, 65, (1975): pp.107-123. http://links.jstor.org.

Lee, A. D. “Procopius, Justinian, and the Kataskopoi.” The Classical Quarterly, new ser., 39, no. 2, (1989): pp. 569-572. http://links.jstor.org.

Lopez, Robert Sabatino. “Silk Industry in the Byzantine Empire.” Speculum, 20, no. 1, (Jan., 1945): pp. 1-42. http://links.jstor.org.

Mainstone, Rowland J. “Justinian’s Church of St. Sophia, Istanbul: Recent Studies of Its Construction and First Partial Reconstruction.” Architectural History, 12, (1969): pp. 39-49 and 102-107. http:/links.jstor.org.

Malalas, John. The Chronicle of John Malala. Eds. and trans. Elizabeth Jeffreys, Michael Jeffreys, Roger Scott, and Brian Croke. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies: Department of Modern Greek, University of Sydney, 1986.

Mitchell, Stephen. A History of the Later Roman Empire: A.D. 284-641. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Moorehead, John. Justinian, Ed. David Bates. New York: Longman Publishing. 1994.

Meyendorff, John. “Justinian, the Empire, and the Church.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 22, (1968): pp. 43-60. http://links.jstor.org.

Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Early Centuries. New York: Alfred A Knopfe Inc., 1989.

Ostrogorsky, George. History of The Byzantine State. Trans. Joan Hussey. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1957.

Procopius. History of the Wars. Book 1. vol. 1, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars. Book 2. vol. 1, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars Book 3. vol. 2, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars. Book 4. vol. 2, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars. Book 5. vol. 3, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars. Book 6. vol. 3 and 4, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars. Book 7. vol. 4 and 5, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. History of the Wars. Book 8. vol.5, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979. 292pp.

—. The Anecdota. vol.6, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

—. Buildings. vol.7, Procopius. Trans. H.B. Dewing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1979.

Rosen, William. Justinian’s Flea: plague, empire, and the birth of Europe. New York, 2007.

Russell, Josiah C. “The Earlier Plague.” Demography, 5, no. 1, (1968): pp. 174-184. http://links.jstor.org.

Teall, John L. “The Barbarians in Justinian’s Armies.” Speculum, 40, no. 2, (Apr., 1965): pp. 294-322. http://links.jstor.org.

Theophanes the Confessor. Chronographia: A Chronicle of Eighth Century Byzantium. vol. 1, Sources of Isaurian History, 2nd ed. Ed. Anthony R. Santoro. Gorham, Maine: Heathersfield Press, 1982.

Ure, Percy Neville. Justinian and his Age. Baltimore Maryland: Penguin Books Ltd., 1951.

Vasiliev, A. A. Justin The First: An Introduction to the Epoch of Justinian the Great. Cambridge, Massachusetts: HUP, 1950.

—. History of the Byzantine Empire. 2nd ed. vol. 1. Madison: UWP, 1964.

Vyronis, Speros. Byzantium and Europe. Norwich, Great Britain: Jarrold and Sons Ltd., 1967.

Watts, Edward. “Justinian, Malalas, and the End of Athenian Philosophical Teaching in A.D. 529.” The Journal of Roman Studies, 94, (2004): pp. 168-182. http://links.jstor.org.

Whitby, Michael. “Justinian’s Bridge over the Sangarius and the Date of Procopius’ de Aedificiis.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 105, (1985): pp. 129-148. http://links.jstor.org.