Jared Emry

The Mayan civilization had a profound view of the world where everything was parallel, chiasmatic, and cyclical. The rising and falling of each star in the night sky are considered in their religion and their rituals are calendric. The traditional Mayan priest is known as an aj q’ijab’, which roughly translates to “day keeper” (Tedlock 7). For the Maya, the marking of time was sacred and all things had a proper place in time.

The central problem in writing histories of Mesoamerican people groups is the majority of written works by the people are now lost and various conquering groups tried to civilize the people by attempting to eradicate their culture and replacing it with their own. Many of the indigenous people also ended up being killed by foreign diseases or slaughtered for gold. Native scribes and scholars were targeted for persecution above any other demographic. The few western scholars who understood the importance of the indigenous literature faced persecution for their attempts to record the indigenous culture, like Fr. Andrés de Olmos and Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún who faced heavy censorship and the destruction or hiding of their manuscripts. Primary documents are scarce and translation is difficult. Many cultures relied on oral tradition. In most cases, the few remaining texts are simply unreadable because the written text hasn’t been deciphered. Fortunately, the Mayan language was fully writable and is now readable. Prior to 1952, the written language was known to be hieroglyphic and the hieroglyphic meanings of the words were known and the hieroglyphics could be translated, but in the process the words lost their parallel meanings. The Mayan language also uses a phonetic structure alongside or with the hieroglyphics. The written languages of surrounding civilizations, including the Aztecs, were pictorial in nature and thus incapable of carrying complex or abstract ideas; contrasting with the complexity of the Mayan texts that were more than capable of carrying the full range of the language. Despite many references to great texts that contained centuries of their history in the journals of the Spanish zealots who burned the books and defaced the writings that were placed in stone, only four incomplete codices are known to survive from the pre-Columbian times. Luckily, a few early translations into Latin texts by Mayan nobles and hidden by village elders for centuries (2-15). Out of the little that remains of Mayan literature, the most significant work is the Popol Vuh which was written by a handful of Quiche Mayans as they watched their civilization dismantled. It is an epic that contains their mythology, their culture, their history, and their philosophy mixed together for the purpose of preserving their heritage.

The Mayan creation mythology is recorded in chiastic structures. While chiastic structure is common in ancient writings, the Mayans mimic the chiastic structures in their religious rituals. It is one of the several forms of parallelism that the Mayans incorporated into their poetry. An example of this chiastic structure illustrates how this appears:

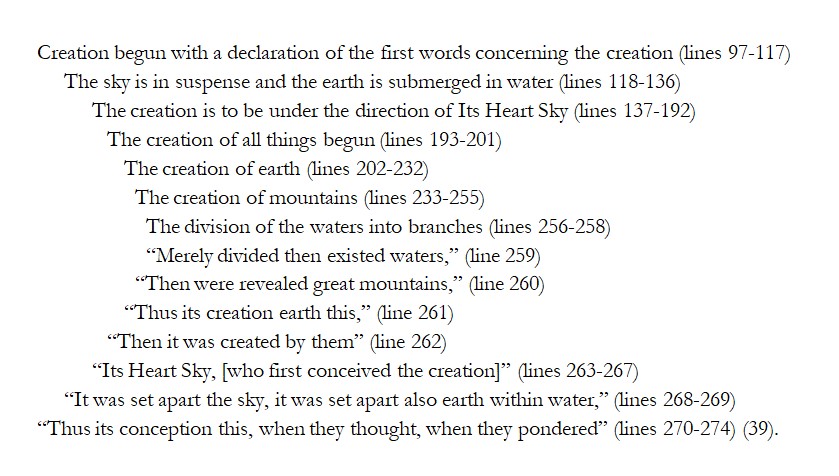

As is illustrated by the example, the story is reversed and told again once it is finished. The Popol Vuh is filled with such chiastic structures with each story being told in a manner and retold backwards. Another interesting factor about the stories are that they are told entirely in what translates to gerunds. It is present tense while the story weaves itself together — twisting and turning chiastically. It is a form of grammatical parallelism where all parts of the text are being taken to be in unity with each part. These parallels are then capped with a singular phrase that binds the sets of parallels together (37-40). Essentially the grammatical parallelism uses language to cause things to appear temporally equal.

Another form of parallelism found in the Mayan mythology is an association of two seemingly unlike things into a binding unity (39). For example, in the myth of the world tree, each compass direction is associated with a color and a god (Phillips and Jones 14). The world tree grew out of the center of the world and branched off in various directions. At the four corners of the globe (it might be noted here the Mayans knew the world was round), new trees would grow in association to new eras. Each era would have a new tree, a new color, and a new god associated with the tree. At the fifth era the cycle would begin anew. At the beginning of each era, more gods would appear and would need to be added to the pantheon.

In their mythology, the Pleiades are associated with protohumans, known as “The Four Hundred Boys,” who are revered as the gods of drunkenness (27). Due to the mythological connotations attached to the Pleiades, the Daykeepers watch the sky to see when the Pleiades rise and fall in order to divine when the proper rituals concerning that portion of the mythology should be done (Tedlock 89-93). Similarly, devotion to time is still found in their calendric divination practices (57, 68). The Daykeepers are known to spread maize over a calendar and to read the placement of the maize on the calendar as a form of divination.

The Mayan Calendar itself the divination would be performed on can be imagined as a series of three gears. The innermost gear would have thirteen notches each correlating to a day in one of the twenty months in the Sacred Almanac. An outer gear would have 20 symbols relating to each month, and they display the name of the day. It would take 260 days for the Almanac to complete itself. There is also a third gear, however, which could be imagined as being outside the other two gears but still attached to the outer gear. This large gear represents a 365-day cycle. This large gear contains a solar calendar of eighteen months that each have twenty days. An additional five days known as the “sleep” evened out the solar calendar. These two calendars in conjunction creates a fifty-two-year cycle that allows each day within the cycle to be uniquely named. This means that a day is only paralleled once every 52 years (Magnificent 31-31). The Mayans also kept other calendars, the most significant being a calendar of Venus. They used complex calculations (the Mayans had the number zero, which added to their astronomical and mathematical prowess) to map out the planet’s 584-day year and its gestation periods in order to properly merge it with the Sacred Almanac and the Solar Calendar (131). These calendars add significant amounts of parallels to time keeping due to the way new parallels may be found based off the combinations of the calendars examined. These parallels were considered sacred as they pertained directly to the mythical stories.

The parallels in the Mayan mythology and histories likely pertain to the parallels in their timekeeping. The Daykeepers spent their lives watching the calendars, and they were the ones who wrote the histories. The chiastic structures and the large amount of linguistic parallels in the ancient Mayan writings show the cyclical nature of the Mayan view of time. The calendars repeat themselves just as their mythologies do. They believed each and every action done could be predicted by their calendars and the proper timing for things were therefore integral to the nature of their world.

Bibliography

Goetz, Delia, Sylvanus Griswold Morley, and Adrián Recinos. Popol Vuh: the Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950.

The Magnificent Maya. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books, 1993.

Phillips, Charles, and David M. Jones. The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya. London: Southwater, 2006.

Spencer, Lewis. Mystical Books of the Mayans. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing, 2010.

Stuart, David. The Order of Days: The Maya World and the Truth about 2012. New York: Harmony Books, 2011.

Stuart, Gene S., and George E. Stuart. Lost Kingdoms of the Maya. Washington, D.C.: The Society, 1993.

Tedlock, Dennis. Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Thompson, J. Eric S.. Maya History and Religion. 1st ed. Norman: U of Oklahoma Press, 1970.