Jared Emry

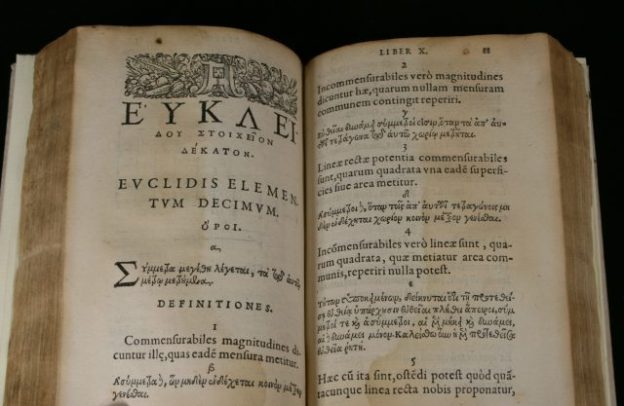

In Euclid’s Elements, Euclid follows a certain architecture for how he structures his logic. Mathematics at its core is pure logic. It is not bound to anything but itself. The logical architecture is in itself the framework of any particular theoretical mathematical reality. In math, the framework can be endlessly changed, but everything else is based upon extrapolation of that framework. Euclid provides a framework and much extrapolation upon the framework throughout the elements. Although this structure can be seen throughout the Elements, focus will be drawn to the first book. And due to space and time constraints, the structure will mainly be focused on the context, up to the twelfth proposition, in relation to the whole, from the definitions to the postulants and from the common notions to the propositions.

When Euclid begins to set up the theoretical reality of the Elements, he begins with three fundamental types of truth. The first of type of truth is definition. The definitions are truths of the factual level. This is this and that is that. It identifies basic parts of his theoretical reality in the same way a scientist tries to reduce the universe into fundamental scientific facts or laws. The first definition is a point is that which has no part. The second definition is a line is a breathless length. These two definitions are fundamental to Euclid’s Elements. They are not based upon each other and can be seen as foundational laws. We also see extensions to some definitions in later definitions. The definitions are the basis on which geometry is extrapolated and other fields in math are based. However, these definitions should not be seen as constant; they are free to be changed to create a new theoretical reality of mathematics.

The second of the three fundamental types of truth are the postulates. A postulate can be defined as a fundamental principle accepted as self-evident without proof. The postulates are claims to be considered true regardless. These can be thought of as a special revelation the same a religion may claim special revelation from a God. Euclid’s postulates are necessary for his theoretical reality to make sense. Some philosophers thought the foundations of reality are ultimately unknowable and only the individual can decide what foundational theory is true for them. Similarly, mathematics in general can have postulates that may seem to concur with reality or not. Since mathematics is pure logic, it is not constrained by any physical reality. Euclid provides in his Elements a definite special revelation of the foundations of his theoretical reality with these postulates. The postulates can almost be viewed as a form of religious dogma or worldview Euclid uses to explain the operations of his theoretical reality. They are Euclid’s five commands. They dictate certain things are possible and these things be considered fact. The first of these is to draw a straight line from any point to any point. This could be said differently as it is possible to create a straight line between two points. The second in the same fashion could be said differently as it is possible to create a straight line so it is straight. However, these slight rephrasing may disrupt some of Euclid’s nuances.

The third of the three fundamental types of truth are the common notions. The common notions are generally accepted logics. They are common for they are generally understood by human sentience. And they are notions because they are abstract reasoning. The common notions reflect the general revelation of man. Man understands the universe he lives in has general rules for functioning. In Euclid’s Elements, these are those rules. For example, the fifth common notion is the whole is greater than the part. It makes sense to the common understanding of sentience a whole is greater than the part, because it is not known to them an example otherwise. The common notions could be left out and more could be added. They act more as a shove toward logical extrapolation, a gentle guide toward the laws of the theoretical reality Euclid is creating in his Elements.

The fourth part of Euclid’s Elements is the propositions. Propositions are hypotheticals that can either be disproven or proven. An assertion is examined through the use of the common notions in the light of the definitions and the postulates. It takes the provided truths and logically analyzes them to see whether or not another truth can be extrapolated from them. Each proposition expands upon the foundation to create multiple and exceedingly more profound layers in the theoretical reality. This profoundness can be seen through the elegance of the each proposition alone, but they can also be overlaid to show their interactions and how they have built upon each other. Each proposition adds to the complexity of raw extrapolated logic. It is from this superposition of the layers Euclid’s theoretical reality can be seen as truly elegant. Euclid takes the layers a step at a time, first proving one thing, and all necessary corollaries and other needed propositions on the layer, before taking the next step up. The ultimate layer of the first book is with proposition forty-seven, the Pythagorean Theorem. The Pythagorean Theorem is well known for being mindlessly memorized as a2+b2 =c2. Although the Pythagorean Theorem taught in that simple algebraic form, it is based on tons of logical extrapolation from several dozen propositions. It should be remembered there are no numbers or variables in the Elements and it is built only by extrapolation and inquisitive shape line arrangements. The Pythagorean Theorem is proven by comparing lines together in context of the previous propositions. Euclid’s Elements are intuitive at their core.

Euclid’s logical architecture in the Elements provides insight to the complicated, because it is the process from the simple to the complicated. It is easier to climb a staircase one step at a time rather than trying to jump from the bottom of a staircase to the top. The book leaves the reader to find the theoretical universe behind the words but gives the reader freedom for his own intuition to guide him. In Euclid’s Elements, intuition is the only path to understanding. To be intuitive with logical frameworks is to find the heart of mathematics. Euclid makes it easy to grasp and to love the pursuit for that reality. On this staircase, each step is provided, but the steps have to be made not memorized. Unlike the bulky mimic taught in many math classes, mathematics is imaginative, fantastical, and intuitive. In this elegance lies the heart of beauty itself, for mathematics is best defined as “the art of expression.”

Bibliography

Devlin, Keith, Ph.D. “What Is Mathematical Thinking?” Devlin’s Angle. Mathematical Association of America, 1 Sept. 2012. Web. 02 Feb. 2015.

—. “Will the Real Geometry of Nature Please Stand Up?” Devlin’s Angle. Mathematical Association of America, 2 Sept. 2014. Web. 02 Feb. 2015.

Lockhart, Paul, Ph.D., and Keith Devlin, Ph.D. A Mathematician’s Lament: How School Cheats Us Out of Our Most Fascinating and Imaginative Art. Jackson: Bellevue Literary, 2009. Print.