Elizabeth Knudsen

The media have a way of taking history and rewriting it to create a tale more easily sold to the public. Most recently, this has been done with the Bible, like in Noah, A.D., and many others. But even more often a historical figure is misrepresented entirely — like Pocahontas in Disney’s classic, who was supposed to be around 10 or 11 years old and had no romantic connection to John Smith whatsoever. However, this paper isn’t another bout with Disney. Instead, the decline of fiction is shown through the portrayal of another historical figure: Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII.

Anne was born in Norfolk and appears to have been the dutiful daughter expected of 16th-century England. In other terms, she, along with her father and brother, worked vigorously for the family’s interest in the court of King Henry VIII. They were known to be early acceptors of the “New Religion” — or Protestant interpretation of the New Testament from Germany — and Anne in particular shared these views with precise, deep, and learned zeal. She had been educated in France since she was six years old, and thus not only became fluent in French but also was gifted with exposure to Renaissance classicism and fashion. The fervor she held for the Reformation was most likely first introduced to her through Marguerite of Angoulême, who later became known as the Queen of Navarre; Gillaume de Briçonnet, her Reformist bishop; and Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, the humanist Bible translator and influential polymath. Indeed, “Lutheran” ideas came to France through these three individuals. Anne’s delight in the French language — it being the third principal language of the movement — became her primary source of the Reformation.

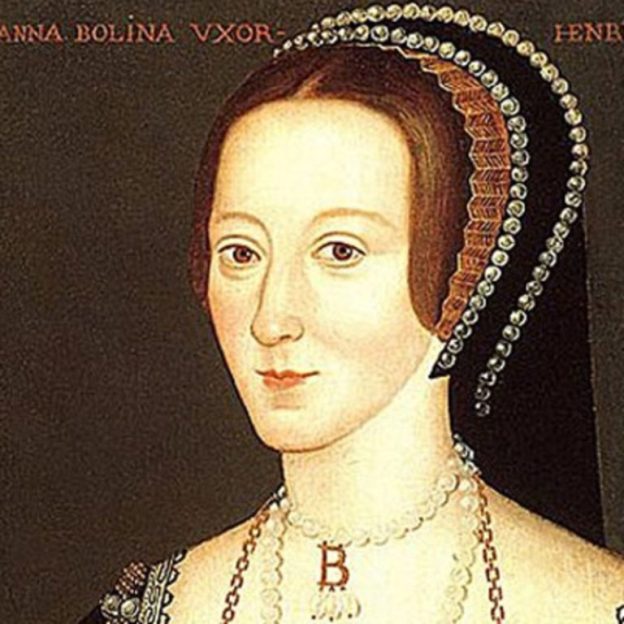

Her relationship with Henry Tudor began with the English king’s impatience for a male heir. Despite the fact the physical descriptions of Anne are not particularly flattering, her vivacity and personal confidence caught Henry’s eye. Around 1526, Henry began courting her. The story of Henry VIII’s break with the church over the annulment of his previous marriage is a well-known one, and it ultimately ended with his marriage to Anne in 1533. Three years later, Anne was executed on grounds of treason, having failed to produce a male heir because of multiple miscarriages. She remained steadfast in denying the charges against her and was equally resilient in holding to her faith.

Enter Natalie Dorman, starring as Anne Boleyn in Sony’s The Tudors television series. It would admittedly be unfair to pin the blame on the actress. For many actors, a job is a job, and they need it. The writers and the production company, however, have no way to escape criticism. The Tudors depicts Anne as a hot-tempered, French-taught seductress and schemer. It follows the basics of her life — her children, her marriage to King Henry, and her death — but in between the glimmers of truth are deep shadows of eroticism. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, it downplays Anne’s faith and magnifies her sexuality. One of the most poignant examples of this is possibly in how Anne’s refusal of Henry’s sexual advances is portrayed. In the TV series, it is presented as one more way she seduces Henry. She encourages him and then refuses him, all the time making him all the more infatuated with her (which was her aim in the first place). However, it is recorded Anne really did refuse to be Henry’s mistress saying she would only be his wife. And if she was, as is believed, a Christian, wouldn’t this refusal be a no-brainer?

So once again, the media are seen portraying a female as a character “more befitting” to the screen. Why is it a singing self-actualizer or a fiery-tempered temptress are better than a noble heroine or a leading figure in the English Reformation? The world’s values have shifted drastically, and not for the better. These shifted values are most prominently shown through the decline of fiction.

Bibliography

BBC History. BBC, n.d. Web. 3 Mar. 2015. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/people/anne_boleyn/>.

Zahl, Paul F. Five Women of the English Reformation. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2001. 10-26. Print.