Jared Emry

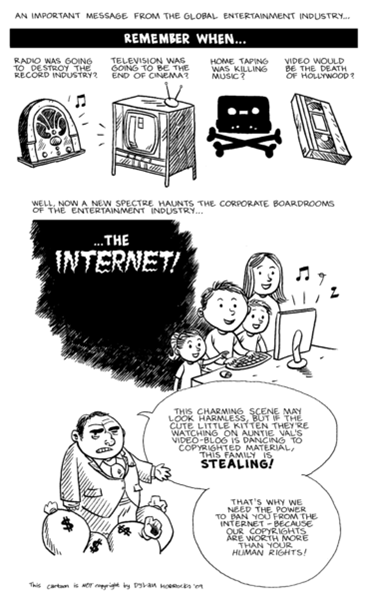

Online piracy has been a subject of heated debate throughout the world for the past several years. Governments around the world have attempted to legislate against online piracy with little success. The most famous legislation in the United States was the Stop Online Piracy Act, or SOPA, but it failed after a widespread protest from many major corporations. Wikipedia even went so far as to temporarily blackout the English version of their site in protest to the legislation. The legislation is meant to be greater enforcement of the copyright law. The government views copyright infringement as a serious crime punishable to twenty years in prison, but millions of people worldwide continue to pirate. Even with the mass proliferation of copyrighted material, serious critiques of the law as a whole are scarce. It is time for a critique of the copyright law.

Copyright was first instituted in 1710 in Britain in order to protect authors from having the content in their books stolen without being paid royalties, and it has since come to cover almost any form of expression or media. Copyright law makes the most sense for reference books, like dictionaries or concordances. The reason is these reference books often could not be produced if they would later be able to be reproduced freely. However, copyright only makes sense for reference books, and these reference books are the only significant justification for the law. Copyright law didn’t enter the United States of America until 1890s. The idea of copyright is a relatively recent phenomenon. The right over how one’s work is copied is a recently invented right and is not directly protected under the Constitution.

Sometimes it is assumed copyright is a moral issue and breaking the law is piracy, plagiarism, or theft; however, this is not the case. When the copyright law is broken, it is not broken for a profit. A modern definition of piracy is to infringe on copyright law, but the word piracy has a connotation of stealing and reselling something for a profit. Online piracy does not have the same connotation, because it rarely involves reselling or profit making. While it may still be considered piracy, it is not the same, and it seems it is only wrong if copyright is moral. The distributers of the pirated material aren’t pirating for money, just reputation. When people say online piracy is wrong, they meant to say it is theft. Online piracy isn’t theft. It isn’t theft, because it isn’t taking money from the copyright owner’s pockets. Hypothetically, if I pirate something online, it probably means I would go without it if I couldn’t pirate it. If someone does not want to spend money on something, they probably won’t. Whether or not it is available for piracy they wouldn’t be getting their money, because the pirate wouldn’t see it as worth the money. Online piracy is also used by potential buyers to see whether or not they like what it is they might buy. Many potential buyers will illegally try the product to test its worth. In this case, online piracy merely acts like quality check. If the product is worth the price, it is bought. Scenarios like this also have a secondary effect on the wallet of the person who created the pirated item, or the originator. Many pirates are also potential buyers who wouldn’t buy the program if they couldn’t test it out. This concept can best be seen in the recent shutdown of one of the Internet’s most popular sites, Megaupload. After Megaupload was shutdown by the government, box office revenues declined. In the end, piracy generated more income for the originators. Theft normally doesn’t give profit to the victim, which by itself implies online piracy isn’t theft! The copyright law is shown here to be harmful to the originators. Also, online piracy isn’t plagiarism, because it rarely involves claiming that someone else’s work is one’s own. Online plagiarism is a completely different topic, but many people mix it in when arguing for copyright laws.

Copyright law harms both parties most of the time and is often the essence of the law being divided against itself. Firstly, it allows for unnaturally high prices of goods which in turn cause fewer consumers. Fewer consumers mean the person’s ideas do not travel around as far or as fast. An artificial bubble occurs that allows second-hand dealers in ideas to exist and prosper. Economically speaking, a forced scarcity is imposed by the copyright law. F. A. Hayek stated, “I doubt whether there exists a single great work of literature which we would not possess had the author been unable to obtain an exclusive copyright for it.” Quite simply, the copyright law does not provide any incentive for original work. There often arises cases in which the original writer too often be forgotten as a footnote, especially in nonfiction. The forced scarcity has never been shown by any study to benefit society as a whole.

There is a simple illustration between forced scarcity and real scarcity. Imagine a typical candy store. It has a certain and definite amount of candy in it, and once the candy is eaten, it cannot be replaced until the next shipment. In this candy store, if one was to take a piece of candy without paying, it would be theft. In this candy store there is real scarcity, so it costs the owner of the store to replace it, and it deprives him of what he deserves for the candy. Now imagine another candy store almost identical to the previous one; however, now all the consumers have the ability to infinitely duplicate each piece of candy after purchase and do what they want with those duplicates. In this second store, the only scarcity is in the human imagination. Several customers would buy some candy, copy it, and hand out duplicates in a variety of ways. Unfortunately, a third party called a government steps in and legislates duplication is illegal without a license from the shop owner. The owner sees less people copying and more of those previous copiers buying and assumes his business is doing better in this false scarcity. However, his candy is reaching a smaller crowd of people, and thus he is actually having less customers than what he could have, and he receives less of a profit from them. This illustration may have a few shortcomings, but it does provide an adequate view of the economics behind the false scarcity. The false scarcity not only causes the shopkeeper to lose profit, it causes the entire society to be impoverished. Copyright law is not about candy, though; it is about ideas. Copyright law keeps society intellectually impoverished. Also, wouldn’t the originator who really cares about the ideas he or she is proposing in their work want their ideas proliferated? Even if they make less virtual money through proliferation, their ideas would reach more people. It is only virtual money, because it is merely a theoretical sum based off flawed assumptions.

There are also great flaws in the copyright law. In America, the copyrights prior to 1972 on music won’t expire until 2065, long after the creators and their children are dead. That means it will take 177 years for the earliest American copyrights to expire. Not only will the copyrights keep the music out of the public domain, it causes a greater chance much of the music will be forgotten and possibly even lost. The 1972 copyrights were only given 95-year copyrights. Copyright law prohibits all audio preservation as illegal. Preservation only happens because the law is not strictly enforced and people are breaking the law. Also, the audio preservation laws apply to more than just music, such as speeches and everything else audio-recorded. This potentially means one might not be able to listen to a J. F. Kennedy or Martin Luther King Jr. speech, because one would need a license to listen. In essence, the copyright law has the ability to censor almost all forms of expression. The only thing copyright needs to control speech and thought is stricter enforcement. The copyright pirates deserve quite a bit of thanks for helping to preserve media (whether or not it is their intention). The piracy often allows originator’s legacies to be formed by the proliferation of their ideas and preservation of those ideas. Which is better for the artist? To have a little extra temporary pocket money that in itself is just virtual numbers based off flawed assumptions? Or to have a greater chance of impacting more people, having their product last longer and be remembered longer, and possibly create a bigger legacy for themselves?

The infringement of copyright law is probably the hardest so-called “crime” governments face in the realm of enforcement. Online piracy is by nature nearly impossible to eradicate. The current idea behind stopping online piracy is by having the Internet service providers, like Cox or Verizon, to block pirate sites with their proxies. SOPA was meant to legislate this concept and was rejected by major corporations because of how a strictly-enforced copyright law could be used. Facebook, Wikipedia, Twitter, and many other companies rejected the legislation because it would allow all their sites to be potentially blocked if any of their users posted copyrighted material without a license. The corporations lobbied Congress to keep it from passing. However, if new legislation exempts their companies, they will gladly accept, because it would bring them all closer to monopoly. New legislation is reappearing even though the majority of Americans disapprove of this entire genre of legislation. The U. N. even has a resolution meant to do the exact same thing as SOPA, PIPA, ACTA, and other legislation. Even though many governments attempt to pass this legislation, the efficacy of such legislation has never been proven. The United Kingdom passed legislation that forced ISPs to block the notorious Pirate Bay. However, the day after the ISPs blocked the site, Pirate Bay had a massive increase of traffic from the United Kingdom. Approximately two million more UK users accessed the Pirate Bay by bypassing the proxies; the problem still has not been resolved. Also, whenever a piracy site is taken down by a government, a backlash occurs. These backlashes are typically denial of service attacks on government websites. After Megaupload was shutdown, Anonymous launched massive attacks against many government sites and all major media corporations who badmouthed Megaupload. Also, in response to their own shutdown, Megaupload ironically hired actors from Universal Studios to create a video defending them. The cost of these backlashes and lawsuits must be large, which shows yet another flaw in the copyright law. The copyright law is almost exclusively enforced for the people with the money, and the average Joe can’t afford to protect against lawsuits from large corporations.

The copyright law is inherently flawed, and enforcement always has lead to more trouble. It also is unpopular and causes many economic problems in any developing society. It continues to impoverish all people and reduce profits. Regardless, copyright law is a dangerous weapon that opens up many excuses for frivolous lawsuits.

Sources

Hayek, F. A. Individualism and Economic Order. Chicago, 1948, pp. 113-14.

Hayek, F. A. Fatal Conceit, 1988, p. 35.

Peukert, Christian and Jörg Claussen. Piracy and Movie Revenues: Evidence from Megaupload. 22 Oct. 2012. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2176246 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2176246