Christopher Rush

From There to Here

Līve’s fourth studio album, The Distance to Here, is a very full, high-quality album. Many of course will think it inferior to their sophomore effort (while called Līve), Throwing Copper — and it is difficult to disagree, in one sense. It is hard to compete with “Lightning Crashes,” “Pillar of Davidson,” “All Over You,” “Iris,” et al. Though, as we saw last time with Sting’s Mercury Falling, it’s just quite possible this effort from Līve, despite the lesser critical acclaim, may be a better, more solid album. Certainly the “lows” of The Distance to Here are not as low as the “lows” of Throwing Copper. Even if the “highs” of The Distance to Here are not as high as the “highs” of Throwing Copper, it would still be a more balanced, thoroughly solid album — but again, the point is not to place albums from the same artist in competition with each other. The point here is to remind ourselves of forgotten gems, one of which is certainly Līve’s 1999 album The Distance to Here.

“The Dolphin’s Cry”

The initial a capella opening is gruff enough and soulful enough to remind us the reasons why Līve were so popular: the band itself was a mix of pounding rhythms and driving sounds, more often than not coupled with intelligent and imaginative lyrics — it is music, after all. The figurative language lead singer/songwriter Ed Kowalczyk invokes in this song are particularly appealing, in a mysteriously intriguing way: “rose garden of trust,” “swoon of peace,” for examples. As with so many high-quality songs, the main theme of this debut song is love: “Love will lead us, all right / Love will lead us, she will lead us.” I see no problem personifying Love as a female for this song: Wisdom is personified as a woman throughout Proverbs. Kowalczyk further reminds us of the importance of living wisely while we are alive, driven by love — quite reminiscent of St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 13: “Life is like a shooting star / It don’t matter who you are / If you only run for cover, it’s just a waste of time. / We are lost ’til we are found / This phoenix rises up from the ground / And all these wars are over.” It’s hard to argue with the veracity of these ideas: it’s unlikely Kowalczyk didn’t have “Amazing Grace” partially in mind, but even if he didn’t, that we think of it when listening to this song supports its own worth. In a way, we are all like phoenixes, needing to be reborn through love, as the war-like enmity between us and God is ended through this rebirth (as St. Paul emphasizes in Ephesians 2). That the song is accompanied by a varied, driving music line is a nice bonus.

“The Distance”

I hesitate to say this song is anti-religion. Religion has gotten a bit of a rough treatment of late, and we would do well to remember “the place where religion finally dies” is Hell, not Heaven. Even so, there is undeniably an emphasis on personal experience — not necessarily “religious” in a watered-down, meaningless way we sometimes have when skeptically talking of “religious experiences,” but in a personalized, individualized, isolated event in which the Ruler of Heaven reaches down to the narrator in a palpable way. “I’ve been to pretty buildings, all in search of You / I have lit all the candles, sat in all the pews / The desert had been done before, but I didn’t even care / I got sand in both my shoes and scorpions in my hair,” says the narrator in verse 1. In a way he is right: it’s not always the right thing for us to do to mimic the experiences or lifestyles of other people who may have had some version of “success” in such a way (what does Jesus say to Peter, after all, but focusing on following Him the way Peter is supposed to, not just mimicking or worrying about how John is supposed to follow Him?). The chorus explains the narrator’s realization in trying to do faith simply by copying the motions and superficially understood lifestyles (i.e., not understood at all) of “religious people”: “Oh, the distance is not do-able / In these bodies of clay my brother / Oh, the distance, it makes me uncomfortable / Guess it’s natural to feel this way / Oh, let’s hold out for something sweeter / Spread your wings and fly.” I hesitate, likewise, to say the chorus is in favor of some ascetic rejection of the physical — more likely the song is reminding us genuine spirituality is not just a superficial “going through the motions,” “do what they do” sort of life. From a purely physical/material perspective, the distance between us and God should be frightening — it truly is unsurpassable simply by our own finite, physical endeavors. What the narrator (and we all) needs comes to him in verse 2: “My car became the church and I / The worshipper of silence there / In a moment peace came over me / And the One who was beatin’ my heart appeared.” The parallel to Elijah’s post-mountaintop experience is inescapable. Few better descriptions of God (“the One who was beatin’ my heart”) exists in rock music. Kowalczyk reminds us it isn’t the expensiveness of the pilasters or the amount of sculptures adorning the walls that make a building a church: it’s the presence of God that makes a lost soul a dwelling place for the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Peace, the One who is beatin’ all our hearts. The final outro thoughts, “This distance is dreamin’ / We’re already there,” are certainly true for a post-justification regenerate Christian. In a real way, the distance between us and God is no longer genuine distance — we only experience it, dreamlike, in a mirror darkly, because we are not fully glorified yet. We have dwelling in us a down payment of Eternal Life. We are already in Heaven tonight in a significant way. This is a truly great song.

“Sparkle”

“Love will overcome / This Love will make us men / Love will draw us in / To wipe our tears away.” That is self-explanatory, isn’t it? Any song about turning from hate to faith, driven by Love, declaring “the Giver became the Gift” (again, what exquisite ways Kowalczyk, for all his faults, describes God), encouraging us not to wait for more miracles or more Messiahs or wasting more chances — but see and embrace this Love now … how can it go wrong? It can’t. This one doesn’t.

“Run To the Water”

After three superb songs, it would be difficult for any band not from Dublin or Stockbridge to continue the streak. Līve, somehow, does it superlatively with “Run to the Water.” Superficially, the song sounds like a Cosmic Humanist/pantheist sort of ditty — but I refute such a claim. The chorus is too much like Isaiah 55:1 to be anything but truth: “Run to the water and find me there / Burnt to the core but not broken / We’ll cut through the madness / Of these streets below the moon / With a nuclear fire of love in our hearts.” I hope someday I have a nuclear fire of love in my heart for God and the things above (the things of Love). The bridge makes the veracity of the song doubly clear: “Yeah, I can see it now Lord / Out beyond all the breakin’ of waves and the tribulation / It’s a place and the home of ascended souls / Who swam out there in love.” The outro again, if a third witness be necessary, solidifies the intellectual, emotional complex of greatness that is this song: “Rest easy, baby, rest easy / And recognize it all as light and rainbows / Smashed to smithereens and be happy / Run to the water and find me there, oh / Run to the water.” I’m starting to realize I don’t listen to this album enough myself.

“Sun”

We sometimes get the impression songs that are too fast can’t have much depth to them, in part because the tempo and most likely the duration of the song preclude much profundity of insight — or, if any impressive bits of terse erudition occur, the brevity of the song prevents much if any development of said terse inkling. Such is the case with “Sun,” but its brief treatment of undeveloped thoughts works well somehow. Musically, it is an appreciated variation being so quick and driving, especially since after this number the album mellows out tempo-wise for most of its remainder. Lyrically, considering the Biblical parallelism so much of the album thus far has displayed, it would not be amiss to think the repetition of “sun” should not allow us to also think of “Son,” at least once in a while — nor would it be reading too much into the song to think Kowalczyk is also thinking of Jesus as the light of the world, especially in the chorus: “Sun sun merciful one / Sun sun / Sun sun won’t you lay down your light on us / Sun sun.” Certainly it would be easy to ridicule such a spiritual treatment of the chorus, favoring a literal interpretation, solely (if you’ll allow the expression). The verses, though, have too much (albeit brief) intellectual leaning toward a richer experience of the chorus: the verses are all about the need to recognize the material world (and this present incarnational experience of it) for what it is, allowing it its limitations and demanding we look beyond it to something more spiritual, more celestial, more meaningful, driven by “the force and the fire of love / That’s takin’ over my mind / Wakin’ me up / Obligin’ me to the sun / Obligin’ me to the sun” the narrator says at the end of verse two. In verse three, we are enjoined to satisfy our earthly, human desires in an appropriate way while we are in this incarnation, “But don’t eat the fruit ‘too low’ / Keep climbin’ for the kisses on the other side” — the other side of existence, the spiritual side of life. The end of the song says “All we need is to come into the sun / We’ve been in the dark for so long / All I need, all we need, all I need, all we need, yeah!” That isn’t inaccurate. So far it is at best difficult to find fault with this album.

“Voodoo Lady”

And then comes “Voodoo Lady.” Admittedly, the low point of the album, though only because of the inexplicably salty lyrics. At least it isn’t as bad as “Waitress” from Throwing Copper, which is admittedly a mild backhanded sort of compliment. Musically, the song is skillfully done and musically distinct from the rest of the album; it captures a Bayou Voodoo sinister mysterious atmosphere well without descending into too much darkness (it is still melodic and digestible, musically) — it is darker than Graceland, but not too dark. The lyrics, though, are off-putting. “It’s got that word in it,” as Frank says. Again, we aren’t here to super-spiritualize this album and “make it safe” by tacking on Bible verses. The earlier songs, though, are too close to the verses mentioned to be over-spiritualizing it. This song reminds me of King Saul’s encounter with the witch of Endor, but I’m not claiming Kowalczyk had that in mind. It seems to have that same sort of feel: dark, inappropriate, sinful, yet something true and surprising happens in the midst of all this haze and no one was really prepared for it, even if it was supposedly what they said they wanted to happen. Still and all, you wouldn’t hurt my feelings if you skipped this one. I usually do, since I’ve heard it before.

“Where Fishes Go”

This song does an impressive job of both maintaining the mood of the previous, somewhat disappointing, song while also reviving the better lyrical mentality of the songs before it. Though the tone of the song is one of irritation (in that the narrator has “found God / And He was absolutely nothin’ like me”), we shouldn’t be surprised when people find God does not match their inferior expectations — not everyone reacts with an upsurge of beautification. Some are, justly to an extent, even more downcast and frustrated, confronted with the realization their perceptions of reality have been altogether incorrect for the entire duration of their lives heretofore. Light dispels the darkness; it doesn’t make it feel better. The sad part of the song is that we are to understand the unfortunate nature of the narrator’s somewhat cowardly reaction — fleeing from the Light of God to hide in the sea “’cause that’s where fishes go / When fishes get the sense to flee.” We take the part of the chorus: “Whatcha doin’ in this darkness baby? / When you know that love will set you free. / Will you stay in the sea forever? / Drownin’ there for all eternity / Whatcha doin’ in this darkness baby? / Livin’ down where the sun don’t shine / Come on out into the light of love / Don’t spend another day / Livin’ in the sea.” On another note, this album was actually among the first ideas I had for journal articles over a year ago when we began Redeeming Pandora, but as the lyrics of this song (and the pervasive beach/sea/ocean motifs throughout the album) indicate, I knew it would be too soon, considering Brian’s death. Even almost two years later, it is still difficult to write about lyrics such as these, but we press on, knowing both the utter correctness and necessity of thinking about these ideas, comforted in part by the knowledge Brian is much better off than we are anyway. Don’t let the people you know stay out in the sea of darkness any longer. As Stevie Smith reminds us elsewhere: they aren’t waving … they’re drowning.

“Face and Ghost (The Children’s Song)”

The tempo slows down again quite a bit, as much of the latter half of the album does. Lyrically, the song is another impressive collection of tensions, conflicting perceptions, ambiguities, and paradoxes. The pervasive motifs of the sun, turning from darkness to light, the distractions of the ocean and the void, the mysterious place where the sky meets the land, all come again in this reflective yet yearning-filled song. The chorus of questions is something we all long for, perhaps increasingly so the further away from the simplicity of youth (innocence) we get: “Can you hear the children’s song? / Can you take me to that place? / Do you hear the pilgrim’s song? / Can you take me there?” We all want to go “high above the lamentation upon the desert plane,” where “the darkness turns to light.” I told you this album was worth listening to.

“Feel the Quiet River Rage”

With a brief return to a fast pace and driving lyrical presentation, Līve grabs us out of our wistful pensiveness with a reminder sometimes pain and water are good things: let’s not be afraid to “suffer the wound” and “never turn from love” and “never turn to hate.” We need to tear down the walls we construct to hide from the storm of living in a world that hates and fears us — that can do more harm to others than it can do good for us. “Tear it down and suffer the wound.” The River of Life, the River of Love has done the saving — let it flow; remember it is still flowing, even though the world is trying to be too loud for us to hear the quiet river rage.

“Meltdown”

Most likely the most abstruse song on the album, “Meltdown” also makes good sense if taken from the hermeneutical perspective we have taken thus far (that Līve is speaking truth more often than not). God is a consuming fire, is He not? Moses and the burning bush? the Pillar of Fire by night for the Israelites in the wilderness? Perhaps the song is about the revivifying effects of being in a committed relationship with a woman — but that doesn’t take away from the possibility that “We’re in a spiritual winter / And I long for the one who is / Fire!” makes a good deal of sense spiritually as well. “How could it be you’ve graced my night? / Like a pardon from the Governor / Like a transplant from the donor / Like a gift from the one who is / Fire! / Amongst the dreamers / You are in my heart.” Sounds pretty much like spiritual justification to me. That would make the eponymous “meltdown” actually a good thing (perhaps the best thing) — the spiritual winter, the heart of stone, all has been melted down by the One who is Fire.

“They Stood Up for Love”

Regardless of what the music video implies (since we all know much if not most of the time music videos are out of the creative hands of the artists themselves), this song is a completely true and possibly the best song on the album, which is a bold claim considering the insufficient praise given the album thus far. “We spend all of our lives goin’ out of our minds / Looking back to our birth, forward to our demise.” Instead we should be the people who “stood up for love,” who “live in the light.” I want to be the person who says “I give my heart and soul to the One.” We are inheritors of a great obligation, from Jesus and Stephen through the Apostles and generations of the Cloud of Witnesses who have stood up for Love, to the kids at Columbine and Virginia Tech and all our brothers and sisters around the world living a much more difficult life for Love than we can even conceive. Let us not let them down. Home, indeed, is where the heart is given up to the One.

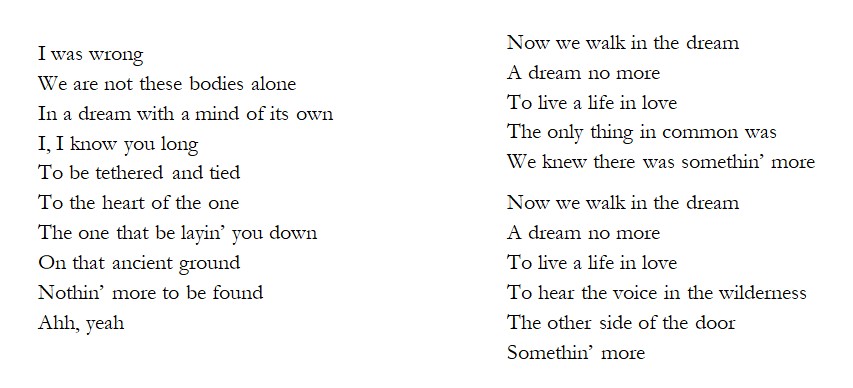

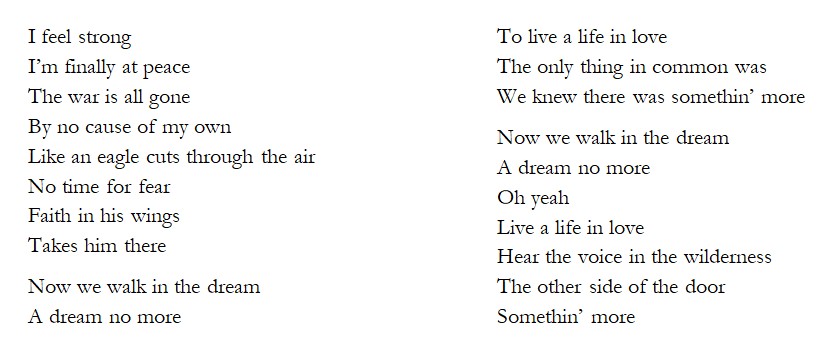

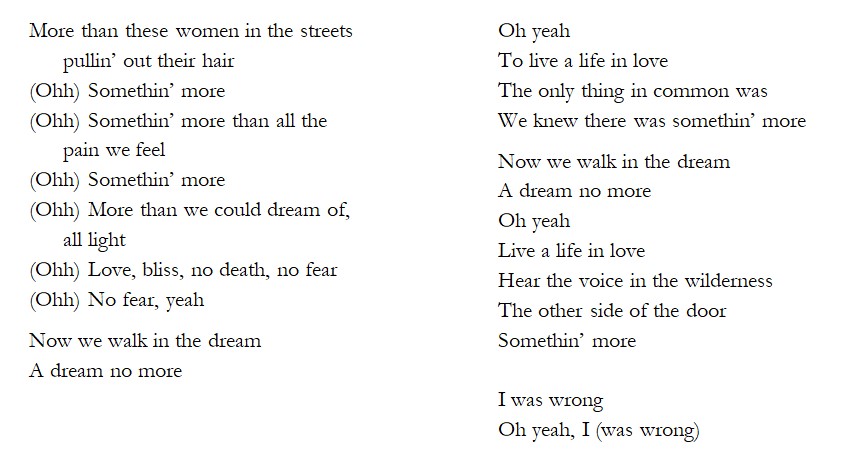

“We Walk in the Dream”

The more I am trying to convince you how great this album is the more I am proving it to myself. For this penultimate song, I’ll just let the lyrics of Ed Kowalczyk do the talking (you can imagine how much better it is when accompanied with the rest of Līve’s music — but then stop imagining by actually listening to this song and the rest of this forgotten gem of an album):

“Dance With You”

It would be awfully disappointing for this album to end with a Cosmic Humanist sort of number, making us rethink all the interpretations and seemingly genuine lyrical offerings we have enjoyed throughout this outstanding album. And it is easy to feel that here: we can too easily get distracted by Kowalczyk’s use of “goddess” and “karmic” and wag a finger and say “nope, not Christian. Karma and goddesses are not Christian.” There’s no arguing that, but I don’t think Kowalczyk is using “goddess” for “God” — I’m pretty sure it’s just a nice way of referring to the lady he’s with — if it is an anthropomorphic description of the setting sun … well, so what? Tolkien, Homer, everybody calls the sun a woman once in a while. Why not Ed Kowalczyk this one time? And “karma” means “action.” Do we dispute the notion our actions in this life affect the life to come? After an album of oceans and rivers in conflict, the narrator is sitting on the beach, finally at peace, at one with God and nature (that can’t be a bad thing to desire, can it?), “aglow with the taste / Of the demons driven out / And happily replaced / With the presence of real love / The only one who saves.” You can’t truly find fault with that, can you? Read the chorus: “I wanna dance with you / I see a world where people live and die with grace / The karmic ocean dried up and leave no trace / I wanna dance with you / I see a sky full of the stars that change our minds / And lead us back to a world we could not face.” I’m pretty sure I want that, too. And if it takes the language of India to recognize this, what’s wrong with that? Verse two is an excellent description of the futility of life without God: “The stillness in your eyes / Convinces me that I / I don’t know a thing / And I been all around the world and I’ve / Tasted all the wines / A half a billion times / Came sickened to your shores / You show me what this life is for.” That last line is definitely one of my favorites of all time. The bridge continues this notion: “In this altered state / Full of so much pain and rage / You know we got to find a way to let it go.” We have to face this world now, while we are here — but that does not stop us from seeing the world, the life, the love to come.

And Back Again

I think I have just convinced myself The Distance to Here is a better album, with only one weak link (how many albums are truly elite from beginning to end, even “greatest hits” albums?), than Throwing Copper . Perhaps that is a bold claim, and as we’ve said throughout, we aren’t trying to set up any artists’ oeuvre against itself in competition, but I think the album supports such a claim (their sixth album, Birds of Pray, is good as well — very Trekian, the way their even-numbered albums are considered better than the odd). Nor do I think it is too much to claim listening to this forgotten gem of an album (with or without “Voodoo Lady”) is an act of worship. If you haven’t yet listened to and enjoyed and worshiped God through Līve’s The Distance to Here, you should get on that now. You will be better for it.