Christopher Rush

The following is the mildly-edited final document I wrote for my Master’s Thesis. It has only been edited to keep the focus on the content, eliminating the extraneous elements required concerning the process of writing the work itself. Part Two and the conclusion will be printed in the forthcoming issue. (Unexpurgated copies are available on request for a small nominal stipend or honorarium, whichever you prefer.)

Introduction

The ancient epics of Greece are foundational to Western Civilization’s literary heritage. From the poets collectively known as “Homer,” operating in an oral culture, come the Iliad and the Odyssey, two contrasting yet connected examples that set the standard for the Western epic. After the exploits of Achilles and Odysseus, other stories and heroes come from a variety of cultures, crafted in new ways representing different values and ideals, each new epic and poet/author remaking and expanding the epic genre itself. Peter Toohey, author of Reading Epic: An Introduction to the Ancient Narratives, declares the ancient world knew several different kinds of epics: mythological, miniature, chronicle, commentary, didactic, and comic are examples of the diverse sub-genres of the epic (2-6). With such variety in authors, cultural background, purpose, and content, it is perhaps impossible to define “the epic” in any satisfactory manner that will account for so many differences. Thus, in order to make this present examination manageable, I focus solely on the two epic poems of Greece, the Iliad and the Odyssey, as the pattern of the epic of Western Civilization refashioned by Babylon 5.

Before examining the texts of the Iliad, Odyssey, and Babylon 5, some initial, albeit broad, definitions of what constitutes the Western epic will help introduce the specific genre of narrative discussed throughout this paper. Charles Rowan Beye, author of Ancient Epic Poetry, a work surveying the genre, provides a valuable historical perspective on the beginnings of the Western epic:

The term epic has come a long way from its origins as the Greek word epos, from the verb eipein, “to utter,” “to sing,” thus, the utterance of the song. Over time, a professional guild of singers cooperated in the evolution of the Iliad and the Odyssey narratives as well as in a host of others now lost to us. The Greeks understood the epic to be a genre of long narratives in dactylic hexameter telling stories that encompassed many peoples, many places with sufficient detail and dialogue to give depth, psychological complexity, and, most important, a historical context. These epic poems contained their history, the history of peoples, the history of the world (284, emphasis in original).

Emphasizing the oral origin of the epic, Beye’s definition begins this understanding of epic as a sensory enterprise: epic was not originally a reading experience but an aural experience for the audience, which Babylon 5, as a television program, similarly provides, while adding a more precise visual component. More significantly, Beye indicates the Western epic is a substantial work that contains “depth, psychological complexity, and … a historical context.” To these essential components Toohey adds that it “concentrates either on the fortunes of a great hero or perhaps a great civilization and the interactions of this hero and his civilization with the gods” (1). Thus the context of the Homeric epics concerns not only the human element of the heroes involved, but also humanity’s interaction with something transcendent: fate, destiny, the divine, and the importance of understanding oneself and one’s place in the universe.

These definitions, taken together, provide a meaningful conception of the major components of the Western epic: 1) a lengthy narrative with a definite structure and shape; 2) a defined central hero surrounded by and relating to other significant, defined characters; 3) a plot of historical significance for the characters and their world; and 4) a thematic element of how the characters come to a better, transcendent understanding of themselves, reality, and their connection to society. The Iliad, Odyssey, and Babylon 5 all utilize these basic epic elements (and more). My purpose, however, is not simply to highlight elements of Babylon 5 as if it is an allegory of the Homeric epics, such as declaring “this character is like Achilles,” or “these episodes resemble a journey like the Odyssey.” The similarities presented are not allegorical but instead serve as examples of Babylon 5’s utilization and reinvention of the various components of the Western ancient epic genre.

In demonstrating the epic natures of the Iliad, Odyssey, and Babylon 5, this thesis utilizes formalist criticism and historical analysis. Through these two analytical tools, I examine the texts of the poems and the episodes of Babylon 5, aided extensively by secondary sources. The Homeric epics have a long history of analysis, though much has focused on their authorship and construction as oral narratives. As that is extraneous to this present examination, I rely predominantly on the content-based historical analyses of the authors who helped define the epic above, Toohey and Beye. Additionally, informing much of my understanding of the structure of epic poetry used throughout the first part of this paper are the narrative composition ideas from Cedric Whitman and the archetypal journey insights from Joseph Campbell.

Drawing upon extensive research (his single-spaced bibliography is twelve pages long), Toohey’s Reading Epic provides an introductory chapter about the general content and style of what constitutes the ancient epic, in addition to the aforementioned history of the epic as a literary genre. Its pertinence and utility are apparent. His emphasis on the heroic code, additionally, which contrasts Achilles and Odysseus as different kinds of heroes, provides several helpful insights for this investigation. Toohey’s knowledge of and extensive research on the subject is clear throughout his work.

Beye’s Ancient Epic Poetry is even more beneficial for my particular focus on the constituent elements of the epic. Offering a more recent work (2006) than Toohey’s (1992), Beye’s commentary provides several useful ideas about Achilles and Odysseus as epic heroes, in addition to the heroic code highlighted by Toohey. Unlike Toohey’s simple bibliographic list, Beye offers a narrative history of Homeric and other ancient epic scholarship. He discusses the aforementioned dominant topic of composition in the field of ancient epic scholarship, citing landmark critics Friedrich August Wolf, Milman Parry, and C.M. Bowra (among several others). Beye laments the dearth of scholarship on the Argonautica and Gilgamesh, though his revised 2006 edition addresses some of the advancements made since his first edition in 1993. His motivation in including commentary on the Argonautica and Gilgamesh, as rectifications of previously-ignored important works, mirrors the motivation of this present inquiry in analyzing Babylon 5 as a serious literary text in the media of televised science-fiction and contemporary epics.

Supplementing the major ideas of Toohey and Beye, the earlier Homeric scholarship of Cedric Whitman provides additional criticism. His Homer and the Heroic Tradition supplies most of the ideas about the dominant structure of the ancient epic, though his focus is admittedly on the Iliad. Like Toohey and Beye, Whitman is clearly fluent in Homeric scholarship. His work is a frequently-cited landmark in the field, though I concentrate primarily on his poetic structure commentary here. Further implementation of his work would only benefit any examination of the epic genre.

Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces is cited heavily concerning the archetypal epic journey used throughout the chapters on the Odyssey and Babylon 5. Campbell’s theories are based in part on the archetypal criticism of Carl Jung, for whom the archetype was a fluid exploration of the “collective unconscious” of a people. Jung’s notions about archetypes as processes are quite fitting not only for Campbell’s epic hero journey pattern but also for Babylon 5 as a whole, whose primary heroes embark on archetypal journeys. Like Whitman, Campbell offers more insight into the epic genre than can be adequately incorporated here, so the focus is intentionally limited.

Other critics cited throughout this thesis such as noted scholars Gilbert Murray, Northrop Frye, and Peter J. Leithart of New Saint Andrews College supply additional helpful ideas, though not to the extent of Toohey, Beye, Whitman and Campbell.

Much of the research cited throughout this work comes from easily accessible sources to the lay reader (Beye makes a similar point in his annotated bibliography). Secondary sources used to supplement the formalist analysis of the individual episodes of Babylon 5 come predominantly from recent interviews and bonus features on the dvd releases of the individual seasons of the series. As the creator of the series, J. Michael Straczynski offers pertinent insight into the television show, its structure, and its message. With the exception of rare, out of print magazine articles and Internet websites (such as “The Lurker’s Guide to Babylon 5,” which provides episode analyses, Straczynski’s commentary, and interaction with the series’ fans), few secondary sources exist analyzing Babylon 5 as a serious, significant literary artifact, which has in part inspired this investigation. The recent interviews of the series’ creative team and cast, from the dvd releases, provide interesting (albeit biased) ideas for this thesis, supplementing analysis of the specific episodes themselves. Other important reference works not cited below include David Bassom’s behind the scenes books such as Creating Babylon 5 and The A-Z of Babylon 5 and Jane Killick’s episode guides, one for each of the five seasons. Their interviews with cast and crew members provide similar backgrounds to the show, but as they are not pertinent to Babylon 5 as a rebirth of the ancient epic, they are acknowledged here only in passing. (Editor’s note: though the original bibliographic information came at the conclusion of the entire work, the works cited throughout part one will be listed at the close of this issue.)

While the Homeric poems themselves are unquestionably worthwhile for any literary analysis, and have been for thousands of years, some critics may question the serious value in attempting to elevate a television show to their status. My thesis posits an affirmative response that it is. Babylon 5 reforms the Homeric epic in style and content, and there is great value in analyzing and understanding it. Babylon 5 gives witness that the influence of the Western ancient epic genre still exists, that the elements that created the ancient epic still resonate in new cultures, new settings, and new media. Their similar hopeful messages of the importance of life given by the responsibility to live well and make wise choices apply to all cultures and all times. The human condition, mankind’s struggle to find a place in the universe despite mortality, resonates as strongly in Homer’s epic past as it does in Babylon 5’s epic future.

Part one of this thesis examines the various contributions of the Iliad and Odyssey to my initial four-part definition of the ancient epic. I do not spend time arguing about the identity of “Homer,” but rather accept the content of the poems as available to the lay reader today through translations. The differences in transmission between an oral culture and the audio-visual medium of television are so apparent that they would distract from the content-driven emphasis of this present work. Chapter one defines the epic elements specific to the Iliad, while chapter two focuses on the Odyssey.

Part two of this work analyzes Babylon 5, how it utilizes the foundational epic components listed above, as well as how it modifies those elements in the ever-changing (yet stable) epic form. Babylon 5 is the major emphasis of this paper, as I seek to contribute to the nascent body of serious criticism on science fiction as a meaningful genre. Part two, likewise, has two chapters. Chapter three addresses the characters: first the two main epic heroes, Commander Jeffrey Sinclair and Captain John Sheridan; and second, alien ambassadors Londo Mollari and G’Kar as different kinds of characters distinct from Babylon 5’s epic heroes. Chapter four addresses the remaining three elements by which I define the Western ancient epic. First are the series’ structure and shape and its plot of historical significance. The grand scale of the program, combined with several layers of internal and external conflicts, makes the show very complicated but cohesive, much like the structured ancient poems. Babylon 5’s dominant transcendent themes of accurate self-understanding and finding one’s place in the universe culminate this exploration of the series as a refashioning of the Western epic genre in a new medium.

Finally, the conclusion focuses on how the fundamental message of hope permeating Babylon 5 at once connects it to the human, mortal core of the Iliad and the Odyssey and also offers a relevant message for all audiences: that life is meaningful and worth fighting for, even with all its flaws and brevity. Babylon 5, like the Homeric epics, engages the audience in the importance of making choices and facing the consequences of those choices with responsibility. Only through accurate self-understanding and a proper knowledge of the nature of reality and one’s place in it can bring a right perspective on the importance and value of all life. In this way Babylon 5 transcends its Western epic foundation and transforms the genre into what its original epic heroes wanted but were denied: the ability to shape one’s own life through free choices.

Part One: The Western Ancient Epic

Chapter One – The Iliad

Structure and Shape

The unifying narrative structure throughout the Iliad is a device interchangeably called “ring composition” by some critics and “chiastic arrangement” (after the Greek letter χ, the chi) by others. The narrative that employs ring composition comes “full circle” in the sense that its end was sufficiently foreshadowed by the beginning of the tale, which essentially returns to the point at which it began. The necessities of plot, even for an epic tale, demand progress and movement, so the nature of the return or completion is sometimes more symbolic than literal, but this does not detract from the efficacy of this narrative technique. This pattern pervades the Iliad in each facet of its structure, from the overarching schema of the entire work to the order of scenes within individual books.

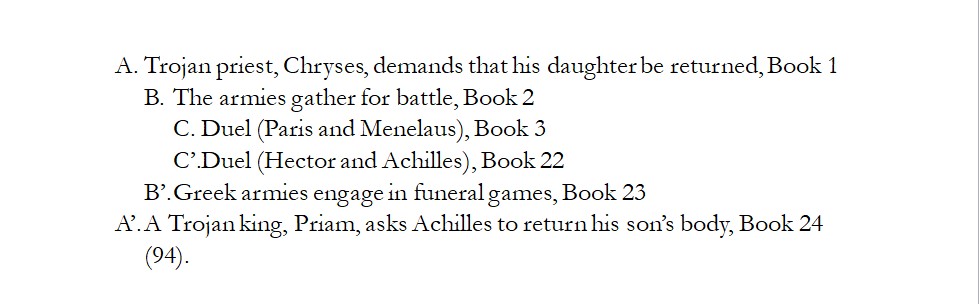

Peter Leithart provides the following diagram, which summarizes many of Cedric Whitman’s ideas about the arrangement of the Iliad:

According to Leithart’s diagram, the poem clearly ends in a similar place to where it began: a Trojan requesting a child from an Achaean. The plot requires the particulars of each request to be different, but the formal structure of the poem is a unifying ring. The cleverness of such a device allows the necessary progression of plot and character movement (even if only internally) while still providing the appearance of similarity in shape and content. Such parallel events bring familiarity and the sense of completeness without the banality of exact repetition. It is this creative structure that gives form to the Western epic genre.

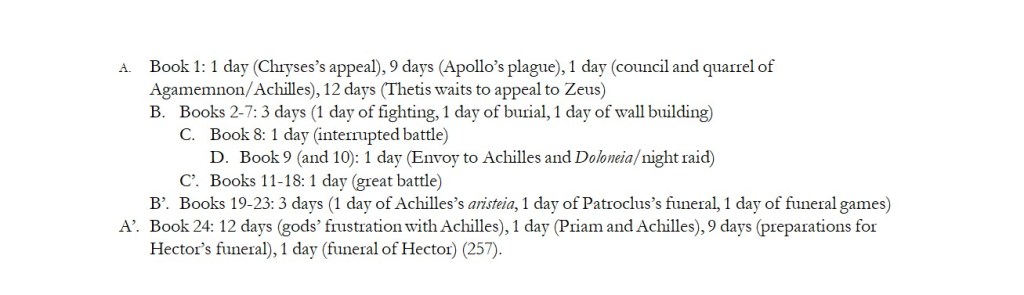

Ring composition guides the progression of time in the Iliad in addition to the direction of its overall plot. Whitman provides a similar diagram delineating the chronology of the poem. The shape of these diagrams resembles an “x” or the Greek χ, hence the term “chiastic” structure.

Again, though the plot content is not precisely identical, the ring similarity concerning the chronological length of the mirrored episodes is remarkably consistent. The length of the mirrored episodes in its written form does not need to be identical — such a limitation would unnecessarily hamper the poem. The key is the mirrored/ring nature of the time as well as the plot itself, which Whitman sufficiently proves.

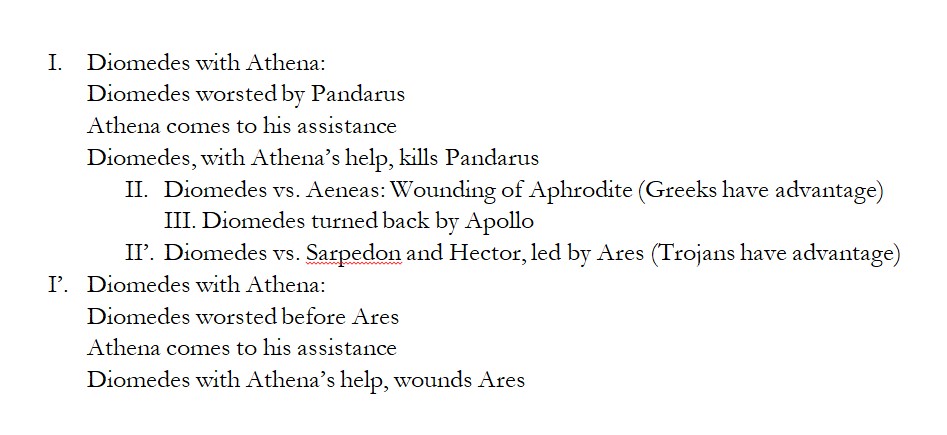

But ring composition does not just inform the overarching structure of the Iliad. It can also be seen in smaller sections within the poem. Book five, relating Diomedes’s mighty battle exploits while Achilles is away from combat, similarly depicts such a pattern in another diagram from Whitman:

Whitman further explains that book five, “[l]ike so many parts of the Homeric narrative, falls into four primary phases, each developed with smaller episodes, and these lie symmetrically on either side of the brief meeting of the hero with Apollo” (266). That Diomedes’s key scene in the poem revolves around his interaction with one of his gods foreshadows here the key epic theme of interacting with some transcendent element of the universe, but since he confronts the gods with physical force and not transcendent understanding, he gains only a temporary (and ultimately inconsequential) victory. This example, as Whitman says, is one of many throughout the poem and thus serves to illustrate clearly that the Iliad uses ring composition or chiastic structure from its overarching plot and time to its individual scenes or episodes.

Ring composition, then, is a fundamental component of what constitutes the Western ancient epic genre. As the first example of this genre, the Iliad’s guiding structure and shape set the pattern for the narrative structure Western epics use to tell their tales, whether as a unifying device or simply in discrete episodes. Regardless of whether the Iliad is a series of stitched-together, disparate tales from an oral composition heritage, the extant poem we have now called the Iliad, as demonstrated by Leithart and Whitman, employs such a narrative structure. Now, the Iliad is a cohesive tale bound together through ring composition, the narrative base for the Western epic. Each epic poem is different and contributes unique variations to the genre, and not all epics utilize ring composition to the extent the Iliad does. Even so, the Iliad, the Odyssey, and Babylon 5, as examples of the Western epic genre, all employ this key narrative structure.

A Central Hero amid Others

Without question, the central hero of the Iliad is Western literature’s first and (perhaps) greatest hero: swift-footed Achilles. Despite his lengthy disappearance in the middle of his poem, the Iliad is Achilles’s story, a story Richmond Lattimore considers a tragedy, which is an unusual thought, considering Achilles survives the Iliad, and his actions in slaying Hector portend the downfall of Troy. Harold Bloom agrees with Lattimore adding that while Achilles “retains the foremost place, [he] cannot overcome the bitterness of his sense of his own mortality. To be only half a god appears to be Homer’s implicit definition of what makes a hero tragic” (70). Son of the human Peleus and the divine water nymph Thetis, Achilles believes at the outset of the Iliad he has inherited only the worst trait from his heritage: mortality. The Homeric Achilles has no invulnerability, and he knows it only too well.

Achilles is continually reminded of his mortality throughout his poem, most notably when his dear friend and kinsman Patroclus is killed by Hector. This sudden loss forces Achilles to seriously ponder his own mortality, especially since Patroclus was acting as Achilles’s proxy on the battlefield — even wearing Achilles’s armor — at Achilles’s insistence. Two other essential scenes, Agamemnon’s envoy to Achilles in book nine and Priam’s plea for Hector’s corpse in book twenty-four, include appeals to Achilles’s mortal father to guide his actions. The envoy and loss of Patroclus contribute to what Bloom calls “the bitterness of [Achilles’s] sense of his own mortality.” By the time of the climactic confrontation with Priam, Achilles is no longer bitter over his mortality. Achilles’s struggle with his mortality, his place and purpose in the universe, his relation to fate and the gods is a significant theme of the Iliad and will be addressed below. Suffice it to say here, the majority of Achilles’s story is a tragedy because of his struggle with mortality and, though he makes peace with it (and Priam) by the end, he knows he will soon die. Yet it is not only his pressing mortality that makes Achilles a tragic hero.

Achilles, as a hero and a mortal, makes free will choices and decisions (though without the ability to shape his destiny). Achilles has a tragic flaw (which Lattimore considers noble), part pride, part occasional subservience to anger, and yet this flaw does not negate Achilles’s freedom to make choices. These choices lead to disaster, culminating in the loss of Patroclus, and this, too, contributes to Achilles’s tragic nature.

Achilles, though, within the confines of the Iliad at least (if not the portentous nature of its tragedy), partly overcomes his own tragedy through the sheer greatness of his personality. Superficially, Gilbert Murray sees him as “young, swift, tall, and beautiful” (206), and though his physical attributes help distinguish him from his fighting comrades (Odysseus’s shortness is frequently mentioned, for instance), there is certainly more to him than that. Lattimore adds that Achilles “is a man of culture and intelligence; he knows how to respect heralds, how to entertain estranged friends. He presides over [Patroclus’s funeral] games with extraordinary courtesy and tact. He is not only a great fighter but a great gentleman” (49). Perhaps, then, Achilles did inherit some positive mortal attributes. Certainly the gods of the Iliad are not characterized by “extraordinary courtesy and tact,” even in their best moments. Even Thetis herself seems only interested in effecting glory and a kind of justice for her son (though some might argue she is being a good mother, her willingness to sacrifice many of her son’s compatriots as attrition for her son’s justice exceeds proper motherly behavior). True, Achilles is not always characterized by “extraordinary courtesy and tact,” but the battlefield is certainly not the place for that. When Agamemnon arbitrarily steals from Achilles and disparages his honor in front of all his fighting peers, Achilles prepares to commit regicide. Since Agamemnon unjustly sullies his honor in a culture that values honor so highly, Achilles may well be within his rights to kill him. Athena intervenes — not because killing Agamemnon is wrong, but because patience will be more beneficial to Achilles later. That he freely yields to Athena (if only for the promise of future gain) exemplifies both his ability to make choices and his heroic connection to the transcendent gods of his universe. As Lattimore describes, Achilles’s “tragedy is an effect of free choice by a will that falls short of omniscience and is disturbed by anger … and his character can be invaded by the human emotions of grief, fear, … and, above all, anger” (47, 48). His anger is thus an essential component of his character and his function as a tragic hero.

The poem wastes no time in bringing up Achilles’s anger: it is the first word in the Greek text. The Iliad is the story of Achilles’s anger: what causes it, what happens because of it, and how it is satisfied and released. His anger “is the anger of pride,” says Lattimore, “the necessary accompaniment of the warrior’s greatness” (48). Because he is great, not only militarily, Achilles knows when his greatness is being challenged, which Agamemnon does. His wounded pride kindles his anger and begins the epic. Though he later treats Agamemnon’s envoy cordially, even greeting them enthusiastically, his response to their entreaties is “clouded” and he “acts uncertainly” Lattimore explains (48) because he is still angry. Appealing to Achilles’s father and, hence, his mortality, does not help as his anger has not yet been satisfied. He rejects their offers and their multifaceted avenues of restoration with Agamemnon. After the death of Patroclus, Achilles transfers his anger from Agamemnon to Hector, transmuting it from a reaction to disgrace into a desire for vengeance, but not even killing Hector slates his anger. It is not until Achilles reconciles with his own mortality that the final appeal to his father by Priam moves him to dissolve his anger and return Hector to his father. Achilles’s anger — what Barry Powell specifies as “the destructive power of anger” (115) — as a unifying motif of the Iliad connects the poem’s ring composition with the nature of the epic hero. The poem opens with a king breaking fellowship with a warrior and concludes with the warrior gaining restoration with not only the king but also the kingly father whose son he brutally murders in anger. Achilles’s anger results in Patroclus’s death, but Achilles is not free from culpability because of an emotion. It is Achilles’s choice to withdraw from battle and send Patroclus out in his stead. That ability (and responsibility) to choose even in his anger also relates to the epic’s theme of the hero understanding his place in society and relationship with the gods, discussed below.

Lastly is Achilles’s motivation. More than his anger, which primarily occurs as a reaction to circumstances, and his struggle to cope with his mortality, Achilles’s fundamental goal in the Iliad explains C.M. Bowra “is not ease, but glory, and glory makes exacting demands. A man who is willing to give his life for it wins the respect of his fellows, and when he makes his last sacrifice, they honour him” (58). By choosing to stay at Troy and ending his short-lived embargo on fighting, Achilles demonstrates that he is a man of action, a warrior, and desirous of his culture’s supreme good: battlefield glory. Vengeance for Patroclus is only part of Achilles’s motivation to return. He knows he can only fully regain his sullied honor by gaining it where it is earned, in combat. He desires to reunite with his culture, as can be seen by his acting as judge and gift giver during Patroclus’s funeral games. He wants to be a part of society, knowing it will soon kill him, since he desires eternal fame, which can only be won on the battlefield. Toohey calls this yearning for glory the “heroic impulse” (9). Though he would prefer to be immortal or at least change the impetuous gods, he realizes he cannot, so he willingly chooses to regain his status and personal glory through combat. For want of glory he allows his comrades to die during his retreat. For the restoration of his eternal glory he willingly chooses the path he knows will result in his own death. Achilles cannot change the end of the heroic impulse in his culture; neither can Odysseus, who similarly follows the Homeric heroic impulse to the restoration of culture through combat. The heroes of Babylon 5 do have the ability not only to change their universe but also the heroic impulse itself. Achilles, unfortunately for him, is forced to resign himself to his mortality and the heroic impulse of his warrior culture, which he willingly embraces after all.

The greatness of Achilles as a hero and member of the warrior culture is depicted in juxtaposition with the other characters in the Iliad. Both the Achaeans and Trojans are heroic, but not to the degree of Achilles, since it is his story. His greatness is pronounced and heightened by the quality of those he overcomes, most notably Hector.

As the Trojan’s last, best hope, Hector provides the best test of Achilles’s greatness. Lattimore explains that unlike Achilles, who willingly abnegates the community of warriors and the heroic impulse for a time, Hector “fights finely from a sense of duty and a respect for the opinions of others” (47). The hero of Troy is caught up in the heroic ideal and heroic culture of combat and glory-winning, but unlike Achilles who tries not to be concerned with the opinions of others, Hector only lives and dies by others’ esteem. That attachment to others is part of his subordination to Achilles and his doom. Lattimore continues, “Some hidden weakness, not cowardice but perhaps the fear of being called a coward, prevents him from liquidating a war which he knows perfectly well is unjust. This weakness, which is not remote from his boasting, nor from his valour, is what kills him” (47). Achilles is not brought down in the Iliad by ignorance or weakness. He chooses willingly what will eventually bring him down. Hector, however, can live only as long as he is deemed valiant by those he defends.

A second major distinction between Achilles and Hector is found in Hector’s key scene of book six, in which Hector leaves the battlefield and returns behind the walls of Troy. Hector, the general by necessity not nature, is normally more comfortable here at home with his parents, wife, and child, yet this farewell scene is fraught with impatience and unease. Hector has not the time to socialize with his family, even though it is clear he would stay here if he could. Hector sacrifices his happiness for his fundamental motivation of fulfilling his duty as the personified final defense of Troy. Hector is more clearly associated with hearth and home than the battlefield, however, and his scenes in book six show this. Certainly, as Bloom notes, “we cannot visualize Achilles living a day-to-day life in a city” (69). As the embodiment of the life Achilles ultimately rejects, Hector is an essential counterpoint to the poem’s hero. Hector is recognized and beloved in the city, i.e., culture, and is fit more for the Odyssey than the Iliad. Since he is in Achilles’s poem, though, he is doomed from the start. James Redfield furthers this representational conflict: “The action of the Iliad is an enactment of the contradictions of the warrior’s role. The warrior on behalf of culture must leave culture and enter nature. In asserting the order of culture, he must deny himself a place in that order. That others may be pure, he must become impure” (91). Achilles, as untamed, uncivilized nature, is an unstoppable force on the battlefield. Hector, since he acts contrary to his true character, has no chance of victory. By itself, that gives no positive reflection on Achilles’s greatness — he is not impressive if his enemy has no chance to beat him. What makes Hector a worthy adversary is his sacrificial character. Hector’s sense of duty (even if driven by a fear of being considered a coward) overrides his desire for comfort, ease, and family living, much like Achilles’s desire for glory overrides his desire for long life and comfort. Achilles meets his inward match in Hector. Hector sacrifices his identity as a father and husband to be a general, assuming his society’s heroic impulse, though futilely. Achilles may not enjoy the heroic impulse either, but he has no satisfactory alternative like Hector does. Unfortunately for Hector, the society of the Iliad values the natural character over the character of culture. Under prepared and overmatched, Hector cannot defeat Achilles.

By conquering his Trojan counterpart, Achilles asserts both his own status as the hero of the poem and his own attributes as the desirable heroic qualities, if not the qualities that simply succeed in this incarnation of the epic heroic impulse. Achilles understands that by choosing to follow the heroic impulse again, even if he would prefer a different life, his fate is an imminent death. He accepts it and faces the consequences of his decision (though others suffer the immediate consequences in the poem itself). Hector, in his final moments with his family, likewise foresees the results of his choice to face Achilles. Unlike Achilles, Hector does not embrace the doom of Troy he presages with his death, including the heartbreaking fate of his wife and child, and tries to avoid it, failing utterly. Hampered by his need to be what others want him to be and his fear of disappointing them (and being considered a coward), Hector’s otherwise admirable self-sacrificial character comes to naught. Despite his greatness, Hector is no match for who Achilles is and what he represents, ensuring Achilles’s place as the epic hero of the Iliad.

Plot of Historical Significance

Little needs to be said here, surely, about the plot of the Iliad. Its chiastic/ring structure in the narrative construction, as well as its thematic cohesion through the rise and fall of Achilles’s anger, shows much of its content. It is possible the lay reader is more familiar with what is not in the Iliad than what is in it. The Iliad does not mention the Golden Apple and the judgment of Paris (except perhaps briefly at the beginning of book twenty-four), Tyndareus’s oath (Helen’s father) of Helen’s suitors to protect her if she is ever abducted, Agamemnon’s sacrifice of Iphigenia, Achilles’s vulnerable heel, or the wooden horse gambit used to end the war.

Essentially, the Iliad concerns only a few days of fighting highlighted by the deaths of Patroclus of the Achaeans and Hector of Troy, bookended by forty-six days (twenty-three and twenty-three) days of virtual inactivity. This occurs in the tenth year of a siege by the Achaeans on Troy, following nine years of coastal plundering, most recently the area of Chryseia. The perplexity (if not part of the beauty) of the Iliad is that its storyline does not fundamentally concern the Trojan War itself — it is more about the rise and fall of Achilles’s anger, and Achilles himself is not even terribly concerned with the war. As he makes clear in book one to Agamemnon and those listening, he has no personal stake in the Trojan War other than surviving and gaining glory and plunder. The cause behind the war, Paris’s abduction of Helen, is only briefly referenced. As a tale of war, combat dominates the middle section of the poem through several duels and large-scale melee battles, especially during Achilles’s absence. When he returns to the foreground, everything else becomes subordinate to the choices and actions of the dominant hero of the epic.

Even though he is the best warrior and the superlative hero of the poem, his own personal journey of choosing glory and accepting his fate is not as momentous a tale as the entirety of the Trojan War itself. What gives the poem historical significance, then, comes from its ancillary components: its background of large-scale conflict, the internal significance to the characters’ personal attachment to the circumstances in which they find themselves, and the poem’s thematic element dealing with the transcendent.

Michael Wood, noted British archaeologist and author, proffers the notion whether or not the Homeric story is real, evidence exists for the possibility of “a” Trojan War, if not “the” Trojan War, and that this conflict between Achaea and Ilios seems to conclude the Bronze Age and the Mycenaean Empire. More recent archaeology supports his ideas, thus his general conclusions about the aftereffects of an empire’s destruction will illuminate the historical significance of the Iliad’s background as a story of what happens/could happen when one people (try to) destroy another:

The central political organization collapses or breaks up; its central places (“capitals”) decline; public building and work ends; military organization fragments…. The traditional ruling elite, the upper class, disintegrates…. The centralised economy collapses…. There is widespread abandonment of settlements and ensuing depopulation (244).

Agamemnon’s merciless attitude (cf. book six) will not be satisfied after ten years with anything less than the destruction of Troy. Since Wood’s summary of what happens to cultures after such destruction is relevant, the Iliad has great historical significance, regardless of the poem’s historical accuracy. As a tale of the fall of a kingdom (through the destruction of Priam’s home and progeny), the Iliad concerns not only the mortality of the individual but of social institutions at large. Additionally, every level of society present in the poem takes its events seriously: this is life and death in palpable form.

The fate of so many characters in the poem is tied to the fate of Troy: once Hector falls, Troy is essentially doomed and so are its inhabitants; Achilles’s choice to stay and kill Hector seals his personal destiny; Agamemnon (as attested to throughout the Odyssey) will have an unwelcome (and brief) return to Mycenae, despite his military victory. The events of the Iliad are meaningful to all its characters, not the least of whom are the dozens of men whose rapid deaths are lamented in the several battle scenes of the poem. As warriors, their lives are given extra significance by their battlefield glory. The terse biographical sketches of so many warriors humanize the poem while simultaneously reminding the reader that the epic poem is fundamentally about humanity in all its facets — vengeance, love, strength, and sacrifice. Mortality and its significance are ever-present in the Iliad. Summarily, the disparate characters react to the grand tale of war in different ways, and each character contributes something different (even if only minutely) to the poem’s overall significance not only as a tale of war but also as a tale of individuals caught up in such a conflict, trying to understand themselves and their world.

A Theme of Transcendent Understanding

The final component of what constitutes the Western ancient epic genre is its thematic element of transcendent understanding. More than just a long, well-structured tale with a mighty hero doing mighty things that transform a culture, the epic features the essential struggle of mankind trying to understand itself, its purpose, and how to interact with the immaterial forces at work in the universe such as fate, destiny, and the divine. The Iliad focuses on how Achilles comes to understand himself, his culture, his fate, and his relation to the gods. Some comments on the Homeric gods themselves will provide a context before examining Achilles’s struggle with the reality beyond the material world.

Few critics see much good within the gods of the Greek pantheon, at best viewing them as amplified humans full of pettiness and greed. Because the sovereign deities of the Iliad universe are licentious, Beye declares they provide “no ideal to which mankind should strive” (57). It is little wonder that Homeric heroes are forced to judge the importance of their lives by tangible standards such as public renown and the amount of booty plundered in war. The gods do not genuinely care for the mortals who do virtually everything on behalf of them; not even Zeus, who supposedly operates throughout the poem for Achilles’s best interest and glory, truly cares for the people. He regrets being forced to allow Sarpedon to die, but he is only “forced” because he esteems fate more than humanity. Aphrodite saves Paris and Aeneas from death, more for her pleasure than because she truly loves them — even though Aeneas is her son. The gods are a significant component of the epic, but their ultimate importance is limited as Powell states because they “are unconstrained by the seriousness of human life … [because] their immortality cheats them of the seriousness that attends human decisions and human behavior. Our acts count because we are going to die, but the gods are free to be petty forever” (47). Powell emphasizes again the importance of free choice as a mark of quality life — the heroes of the Iliad are responsible for their actions because the gods, according to Lattimore, “do not change human nature. They manipulate [the characters], but they do not make them what they are. The choices are human; and in the end, despite all divine interferences, the Iliad is a story of people” (55). The significance of being a free mortal human manipulated by the gods is what Achilles struggles with throughout his poem.

As the central hero of the poem, Achilles’s struggle with his identity and culture is the most significant struggle of this kind. Diomedes’s encounters with the gods affect him, but he soon disappears from the story. Hector has the ability for a time to know himself and his future, but he does not accept what he sees and so is destroyed. Redfield makes this point clear, that this transcendent ability is central to the Western epic genre:

It is a peculiarity of the epic that its heroes can, at certain moments, share the perspective of poet and audience and look down upon themselves…. Achilles tests the limits of the heroic; when he commits himself to the killing of Hector, he sees his own death also before him and accepts it. He is thus an actor who both acts and knows his own actions as part of an unfolding pattern (89).

Achilles, Odysseus, and the characters of Babylon 5 thus have a unique ability as epic heroes: they can, when the time is right, see beyond their own situations and know where they fit in with their reality. Epic heroes such as Achilles are aware that their actions are choices, that those choices have consequences, and that they must face those consequences with responsibility for having freely chosen to do what they do. Not all characters in the Western epic are aware of themselves and their place in their culture — only heroes have that ability, what Lattimore calls prescience, to see beyond themselves.

In order to understand himself, his culture, and how he fits in, Achilles must first be separated from his culture, which occurs when he chooses to leave the battlefield after Agamemnon insults him in book one. Because Agamemnon cares only for his material wealth and status, he has no chance of understanding his culture (he accepts it readily) or transcending it, and so he cannot be a true epic hero like Achilles. Achilles is so upset with Agamemnon’s insult that he eschews the culture and heroic impulse that drove him to Troy nine long years ago. As a warrior withdrawing from battle, notes Toohey, “Achilles begins to reject the heroic world; as a way of life … it is suddenly making demands upon him that he cannot tolerate” (124). If the heroic impulse allows a leader who is only a leader because of material prosperity and not inner quality to steal property and besmirch honor in front of those who bestow such honor, Achilles will have no more of it, and so “he retreats from his society to take refuge in what is left, his individuality” (125), allowing him to slowly come to know his culture from an external vantage, and thus can become a full, unique epic hero.

When he learns of Patroclus’s death, and that he has tarried from the battlefield and his heroic culture too long, Achilles the epic hero gains his first moment of heroic prescience or transcendent understanding. Achilles is aware that his response to the death of his friend (his freely made choice) will seal his fate at Troy in what Murray calls his “special supernatural knowledge that his revenge will be followed immediately by his death” (142). As a hero, he is both bound by fate and a partial maker of his own destiny through his choices. Having spent enough time away from the heroic culture, Achilles knows that it is flawed, but he accepts at last that it is the only way of life for him, but he now understands it, unlike the other mortals. He never claims that the heroic impulse lifestyle is morally wrong or fundamentally uncharitable; he simply realizes that it is terribly costly, and, knowing the cost, chooses to return to the heroic world.

Achilles’s greatest militaristic achievement in the Iliad, the slaying of Hector, is bookended by his two heroic moments of heightened understanding. During the action, he has not the time to think or philosophically observe — that is part of the tension of his function as an epic war hero; he can understand his actions and himself before and after what he chooses to do, but he also has to act. Once he accepts his mortality and his fate by choosing to kill Hector he loses his transcendent understanding for a time (as evidenced by his mistreatment of Hector’s corpse) but regains it again at the close of the poem when Priam asks for the return of his son’s body.

Achilles’s confrontation with Priam is a remarkably different scene and tone compared to the beginning confrontation with Agamemnon, though it fulfills the ring composition structure of the poem. Instead of the anger of book one, Achilles responds to the Trojan’s request with a silent, introspective gaze. Priam appeals to Achilles’s father, reminding him again of his mortality, but Achilles has already accepted this. Murray elucidates that this quiet deliberation again “enables Achilles to know his situation and no longer merely experience it. What was baffling in its immediacy becomes lucid at a distance. Achilles surveys and comprehends his world and himself” (87). There is no longer any need for anger, since Achilles the epic hero finally understands his role in life and accepts his own mortality. As he makes clear to Priam, he has even begun to understand the gods themselves, at least from his limited, mortal perspective.

Before returning Hector’s body, Achilles tells Priam a story of Zeus’s two jars, one of good and one of evil, which Zeus sprinkles out indiscriminately on humanity. According to Achilles, humanity can get no grace, no direction, no hope from the gods. His frustration is ironic, considering Zeus has been manipulating the events of the Iliad to help Achilles regain his glory. Zeus refutes Achilles’s notion early in the Odyssey when he declares humanity blames the gods for their misfortunes when they actually receive what they deserve based on their free choices. Achilles’s logic is flawed, but his final conclusion is correct: mankind is responsible for its actions, regardless of the gods. He understands this as an epic hero. He chooses to return Hector to Priam just as he chose to kill Hector earlier, even believing the heroic world is flawed and ruled by disinterested deities. He cannot do anything to change it, since only he understands it, but he does what he can and returns Hector to his father, easing a fellow mortal’s suffering.

This is not to say Achilles is a completely changed person. Epic heroes are essentially monolithic. They learn the true nature of themselves, the universe, and mankind’s place in it, and they make decisions and face the consequences of their actions, but they are not inwardly transformed. Achilles returns to his flawed heroic world because it is the only culture around — and he truly values it, even after he more fully understands it and mankind with all its faults. Epic heroes do not always understand themselves or their universe — it is an attribute they must learn and develop — but when they face their most critical decisions, epic heroes distinguish themselves from their companions not only by their superior physical traits but also their superior mental awareness and transcendent understanding.

The Western epic explores the important questions of life, such as meaning, purpose, and destiny, and epic heroes grapple with these issues, sometimes with, sometimes against the gods of their universe. The gods do what they do, but so do humans. As mortals, humans have a limited time to live meaningfully, and heroes of the Western epic embody the importance of life lived well. Mankind is responsible for his choices, and Achilles’s acceptance of that responsibility is part of what makes the Iliad a meaningful story about the worth of humanity, in part because of its ability to make choices and live well in what little time it has.

Chapter Two — The Odyssey

Structure and Shape

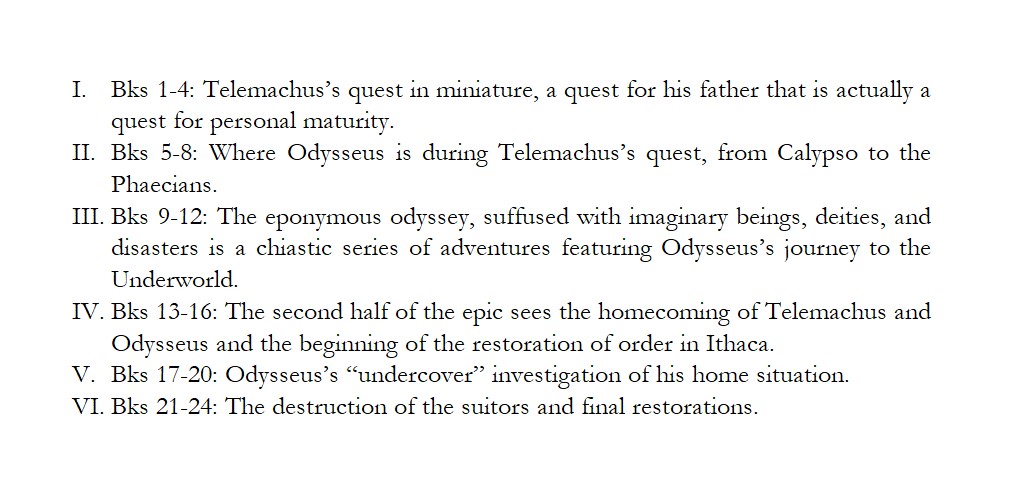

Unlike the Iliad, the Odyssey does not have the same over-arching ring composition or chiastic structure, though the most famous part of it — Odysseus’s magical journey — does have a loose chiastic arrangement in which each hostile episode is followed by an equally dangerous peaceful episode, all attempting to prevent Odysseus from returning home, according to Leithart (cf. 180-181). This makes sense, as the Iliad is a grand war poem whose characters do not physically go anywhere and the Odyssey is Western literature’s archetypal journey story. The Odyssey is a series of six quartets in the chapter/book arrangement in which the poem exists today. Without belaboring the plot synopsis here, it is possible to define the structure of the epic with another diagram:

As a journey story whose theme is restoration from disorder to order, it makes sense the ring composition technique is not as applicable to the Odyssey. If Odysseus ends where he begins, even in a symbolic way, then he has failed in his quest and his epic poem is a complete disappointment. Even with little of the ring composition that dominates the Iliad, the Odyssey is a lengthy tale with a definite structure and shape. It is a journey toward restoration of both Ithaca and its king’s family.

A Central Hero amid Others

In addition to its limited use of ring composition while incorporating a new narrative structure, the Odyssey’s hero also expands the nature of the Western epic begun by the Iliad. Odysseus is the antithesis of Achilles. Instead of the emotional hero who gains understanding and reconciliation, Lattimore explains that “Odysseus has strong passions, but his intelligence keeps them under control” (51). Odysseus never acts out of uncertainty or confusion. Throughout the Iliad Odysseus distinguishes himself from his compatriots. He restores order when Agamemnon’s test of the troops backfires; he upbraids Achilles twice, privately and publically. He is deemed responsible as a spy and warrior during the night raid, and he is trusted as the diplomat to return Chryseis to her father. As a different kind of man, Odysseus takes the epic hero role in a new direction.

Odysseus, as a different kind of man, survives both the battlefield and the different obstacles on his supernatural journey back home. By choosing mortality and war-won glory, Achilles’s peace at the end of the Iliad is tenuous at best, and since he is fit only for the battlefield, he would not survive the world Odysseus conquers. Odysseus’s goal is to return home and restore his kingdom, and when he does, the reader is left with the sense that Odysseus’s line is secure in the person of Telemachus, his son. In order to survive his return and complete his restoration, the new hero must use his cleverness and guile — Achilles-like brute strength will not defeat Sirens or a Cyclops.

Through his mental cleverness, Odysseus frees his men from the cave of the Cyclops. Knowing brute strength would never enable them to remove the stone barrier keeping them captive, Odysseus tricks the Cyclops into both believing he is “nobody” so no consequences will come from his identity and also drinking too much wine so they can effect their escape. Odysseus’s identity, which he frequently abandons during his journey, is the Odyssey’s key theme of dealing with the transcendent: self-knowledge in a world of transformative magic and death. Similarly, Odysseus’s cleverness allows him to keep his men safe from the Sirens’ song. While he allows himself to hear their beautiful song and is tempted to follow it, his cleverness ensures his security. Strength cannot conquer the call of the Sirens; only a new kind of epic hero with wits to supplement prowess can survive the post-war challenges of the Odyssey.

As an epic hero, Odysseus is multifaceted, just as Achilles was more than just an angry warrior. Not just a clever survivor, Odysseus is also a liar. Beye translates this otherwise nefarious trait into a necessary element for Odysseus as a survivor in such a dangerous, complex world: “Never a straightforward person, he is cunning and always suspicious” (149). Beye sees Odysseus’s liberal use of deception as his “greatest strength” (149). In a world dominated by amoral deities, it is understandable that an epic hero is not bound by any inner or external compunction of morality. “Everybody lies,” says Commander Sinclair of Babylon 5. Odysseus rarely tells the truth because survival is key, not being “good.” As a survivor of a different kind of battle (the voyage home), Odysseus expands the limits of the Western epic hero by using whatever resources he needs (such as cleverness and moral liberality) to overcome any situation in order to survive. Like Achilles, Odysseus chooses to be the hero he must be in his circumstances. Achilles must follow his heroic impulse back to the battlefield; Odysseus must follow his heroic impulse to complete his epic journey. Odysseus’s journey is not only an important variation of the epic story but also a key aspect of his heroic nature. Joseph Campbell’s delineation of the various paths of the archetypal hero journey in The Hero with a Thousand Faces demonstrates Odysseus’s epic path in three main stages: departure, initiation, and return.

Departure

The hero’s journey begins with his departure from what he knows, heeding what Campbell refers to as the “call to adventure” (36). Odysseus and his companions heeded Agamemnon’s call to adventure ten years before, beginning the Trojan War. Odysseus now heeds the call to return home. As an epic poem, the Odyssey begins in medias res (in the middle of things), so Odysseus has already begun his return home when the poem begins. The next phase of the departure is the advent of supernatural aide or “protective figure” (69). Athena provides this function for Odysseus throughout both Homeric poems, most notably by transforming him into an unrecognizable old beggar upon his return to Ithaca so he can reconnoiter his situation secretly.

Even with divine assistance, Odysseus encounters many conflicts during his journey, especially while on his magical journey of fantastical creatures recounted in books nine through twelve (the section using ring composition). It is during this phase of his journey that he has no divine help from Athena, allowing his true greatness as a new kind of epic hero, utilizing strength, cleverness, and deceit to shine. The final element of the departure is the “belly of the beast” (69), which Campbell describes as a passage into “a form of self-annihilation” (91). This is fitting, since meeting the Cyclops is Odysseus’s first test of preservation by non-physical means, and here Odysseus begins his thematic journey of self-understanding in his world through his ever-changing identity. By calling himself “Nobody” or “No-man,” Odysseus further distinguishes himself from Achilles as an epic hero who outwits his opponents instead of simply out fighting them, simultaneously fulfilling Campbell’s “self-annihilation” by destroying or disguising his true identity throughout his journey.

Initiation

Few literary protagonists encounter stranger characters and trials than Odysseus does in his poem, especially during his return section, which Campbell calls “a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms” (97) and a “long and really perilous path” (109). Odysseus, as a hero unlike Achilles, cannot solve his problems by accepting his fate and killing his foes. Leithart considers Odysseus on his journey “a ‘man of twists and turns,’ who wears disguises and assumes false identities, who adapts himself and waits patiently for his opportunity to strike … [as] a man of cunning words” (150). The battlefield never changes; Achilles only changes in his understanding of it. Odysseus’s journey changes at every stop, and he must change and adapt too quickly during his initiation phase for transcendent self-understanding or prescience to do him any good.

The next sub-phase of the initiation according to Campbell is the confrontation with the Mother Goddess figure or the Temptress, and Circe fulfills both of these roles well. Campbell describes the Goddess as “the paragon of all paragons of beauty, … the incarnation of the promise of perfection” (110, 111). Circe beguiles Odysseus’s men, and Odysseus willingly beds her to restore his non-clever crew. This is another example of Odysseus’s readiness to be and do whatever is necessary to achieve his amoral goal of returning home. Despite his claims of love and faithfulness to his wife Penelope, Odysseus chooses to abandon physical fidelity to restore his family. As the Temptress, Circe temporarily succeeds in delaying Odysseus for her pleasure, but he eventually resumes his return; Circe then acts as the Mother Goddess figure, directing Odysseus to the next source of guidance and information: Tiresias in Hades.

Odysseus’s encounter with Tiresias represents a metaphorical fulfillment of the next aspect of Campbell’s hero adventure, the “atonement with the father” (36-7). It is metaphorical because Odysseus reunites and atones with his literal father at the end of the poem. Here, Tiresias represents wisdom and lucidity, attributes clever and guileful Odysseus needs. By making a sacrifice that appeases Tiresias, yielding to his nature and wisdom, Odysseus recognizes that he does not have everything alone he needs to complete his quest. He will need Athena’s help later, and here he needs the advice and guidance of Tiresias to reach his destination and become a full, self-aware epic hero.

After the reconciliation with the father, Campbell recognizes the archetypal hero achieves a kind of apotheosis, a “divine state to which the human hero attains who has gone beyond the last terrors of ignorance” (151). Odysseus travels into the Underworld, gains wisdom and advice from Tiresias, and safely navigates out. He is about to lose his crew and possessions, but he surpasses the fears of ignorance and knows where to go and what to do, which is for him the last phase of the initiation, the “ultimate boon” (37). Odysseus will not be fully satisfied until his quest is complete, but he knows how to do it.

In an ironic way, Odysseus is offered the enjoyments of the ultimate boon without fully returning home. After losing his crew and possessions, Odysseus encounters Calypso, another Temptress figure who succeeds in wooing Odysseus for seven years with the ultimate boon of a home and rest from his journey. When his resolve to return home to his family overcomes his desire to be through with his journey, Odysseus again receives the supernatural aid of Athena, and he begins the final phase of his quest.

Return

Odysseus’s final phase begins when he receives what Campbell calls “the rescue from without” (37), which come in the forms of King Alcinous and the Phaecians. This final stop before Ithaca completes the ring structure section of the Odyssey. Odysseus arrives at Troy with nothing and leaves with the spoils of war; he arrives at Phaecia with even less (no army, not even clothes) and leaves with more treasures than he earns at Troy and, more important, a better understanding of himself and his limitations.

Completing the symmetry of the hero’s journey, Campbell refers to the “crossing of the return threshold” (37), adding that it is a brief time of reflection in which “[m]any failures attest to the difficulties of this life-affirmative threshold” (218). Odysseus loses his crew, his Trojan plunder, and twenty years with his wife and child — Telemachus’s lifetime. He uses his cunning, strength, and guile to succeed, even relying on supernatural and human aid to return home. Yet his work is not done, for according to Campbell the “returning hero, to complete his adventure, must survive the impact of the world” (226). For Odysseus, this is his confrontation with the suitors.

Having learned what he needs to learn as an epic hero, Odysseus is finally able to slough off all of his hidden identities and resume his place as husband of Penelope and ruler of Ithaca. With his son’s assistance, Odysseus mercilessly eradicates the suitors and his disloyal servants. He fulfills Campbell’s penultimate sub-phase of the return as the “Master of the Two Worlds” (37), as master both of his physical territory and family and master of his sense of self and place in the world. With Athena’s intervention in eliminating any retribution from the suitors’ families, the knowledge that his son will be a worthy successor, and restoration with his wife and father, Odysseus completes his quest and ends his heroic journey with what Campbell calls the “freedom to live” (37). He knows who he is and restores his kingdom, but he has not lost his guile. Epic heroes do not change. Odysseus, finally at home, will live fully content with his unchanging nature.

Like Achilles, Odysseus is surrounded by complementary characters who further distinguish his status as the epic hero of the poem. In a tale of household restoration set against the backdrop of the heroic world, it is fitting to contrast Odysseus as a hero at the end of his quest with his son Telemachus the burgeoning hero.

Telemachus is a hero in miniature, and through him the poem demonstrates how Western ancient epic heroes are made. Not every man in the ancient world is a hero, as this poem shows distinctly through the self-centered groups of Odysseus’s crewmates and Penelope’s suitors. Growing up surrounded by women, servants, and un-heroic gluttons, Telemachus has no initiation into the life of the hero until he embarks on his own quest to find his father. In doing so, he also seeks himself, his identity as a warrior’s son in a heroic world, for he cannot learn what it means to be an epic hero in his childhood company at home. Beye points out that “Telemachus emerges from the perversion of human behavior that the suitors are enacting in his childhood home to encounter proper behavior at Pylos and Sparta” (183). By literally leaving his home, he figuratively leaves behind childish things, including the immature lifestyle of indulgence and lasciviousness of the suitors. Under the experienced tutelage of Menelaus at Sparta, Nestor at Pylos, and Nestor’s son Peisistratus who models what Telemachus should be, the son of an epic hero and warrior, continues Beye, Telemachus “becomes more aware of his heroic parentage, [and] he does achieve heroic stature himself” (155).

But epic heroes are not made in the classroom; Telemachus needs an opportunity to apply his newfound heroism, and reuniting with his father is not enough. The destruction of the suitors is Telemachus’s passage to manhood and final preparation for the heroic life. By the end of the poem, Telemachus puts his mother in her proper place, unites with his father, and rebukes the suitors before aiding his father in slaughtering them all as a warrior. The Ithacan line is secure with a third generation epic hero.

Plot of Historical Significance

The historical significance of the Odyssey comes more from its thematic components than the direct plot itself: battling Cyclops and Sirens are not commonplace, and slaughtering suitors is not a typical method of restoring one’s home and family. One key theme of the Odyssey with substantial ramifications today is its expression of social behavior. The Iliad portends the causes and effects of the destruction of a city and civilization; the Odyssey exemplifies how people live together and restore civilization.

The demonstration of hospitality is the Odyssey’s main expression of proper social behavior. Each member of the Ithacan royal family encounters the improper abuse and proper use of hospitality in many ways: the Cyclops’s dearth of hospitality results in the death of seven of Odysseus’s crewmen; Circe’s and Calypso’s surfeit of hospitality result in the wastage of several years during Odysseus’s quest to return home; the suitors’ abuse of Penelope’s hospitality is the major trial she must overcome in the poem and motivates Telemachus to begin his quest for maturity. The Phaecians’ hospitality to Odysseus ensures his safe return to Ithaca. Through their hospitality, Odysseus’s faithful servants distinguish themselves from those loyal to the suitors. Because of her hospitality to him while he is disguised as a beggar, Odysseus gains hope that Penelope is still faithful to him. Telemachus receives much hospitality from Nestor and Menelaus, and through their actions he becomes a proper hero in a proper society, a man who is kind and generous to strangers and others in need. The Odyssey clearly emphasizes hospitality as a distinguishing aspect of proper society. Those who abuse it, the suitors and Odysseus’s crew, are all punished, usually with death. As a theme of society’s right conduct, the Odyssey’s message of the importance of hospitality is still significant today. Choosing to be gracious and hospitable, especially to strangers and those in need, is an admirable quality worth emulating, and helps maintain a proper society.

A Theme of Transcendent Understanding

More than their historical value, proper hospitality and social conduct — how to live in society — are part of the Odyssey’s theme of transcendent understanding. The poem from beginning to end is about restoring broken societies. Ithaca at large is crumbling and must be mended; Ithaca’s ruling family also needs to be reunited. This tension is continually compared to Agamemnon’s failed family and his son Orestes’s slaying of his own mother and her lover. Orestes’s actions are praised throughout the Odyssey, and Telemachus is often enjoined to be like him if it becomes necessary. Not only do the heroes of the poem require proper social conduct, but the gods do also. Toohey claims “that Zeus does indeed desire a just world and that he will act through heroes such as Orestes and Odysseus … to establish this state” (46). The restoration of proper social conduct, with correct hospitality as one crucial aspect of it, then, is mandated by Olympus. Orestes is praised for avenging his father’s murder. Odysseus is praised for eliminating the suitors because they abuse hospitality and proper social conduct. Odysseus’s crew is justly killed because they transgress divine social boundaries by eating Helios’s cattle. The greatest injustice in the Odyssey is the abuse of proper social conduct, which is punished by the gods through the free agency of mortal heroes.

Those who choose to obey and restore right social relationships are the epic heroes of the Odyssey, joining the poem to the Iliad. Achilles separates himself from his peers in part because he hates Agamemnon’s abuse of hospitality when he takes something that was rightfully given to him by his peers; in one sense Achilles restores the proper social structure by his generosity to the combatants in Patroclus’s funeral games in book twenty-three and, most significantly, by returning Hector’s body to Priam at the end of the poem. Achilles learns that his connection to the gods and his society is intertwined with proper social behavior, which he demonstrates by his actions. Similarly, Odysseus and Telemachus learn the connection of the epic hero to society and the gods through proper social action. Hospitality is a choice made by epic heroes because they understand the nature of their world better than non-heroic people; they know their choices have consequences for themselves and others, and only through proper human interaction can society be maintained. Odysseus spends twenty years returning home after a great social injustice (Paris’s kidnapping of Helen); he is certainly motivated to choose to restore right social interaction, especially in his own home.

Choice is essential in the Odyssey. Beye notes that “Athena gives Telemachus advice, but he acts upon it and gets the story moving” (151). As a nascent epic hero, Telemachus quickly learns the importance of choices and facing their consequences. Since he is a hero, separate from his fellows, his responsibility is greater, in part, because he, like all epic heroes, understands the universe and his place in it better than others. As a man and future ruler of a kingdom, he learns to be generous and hospitable to those in need, not just because the gods prefer it, but because it is the proper way for society to interact, especially epic heroes who understand society better than non-heroes do.

Odysseus, as an epic hero, chooses to restore order and punish those who abuse proper social conduct. He does this not only as an epic hero who knows the gods and the nature of the universe (clearly better than his crew does), but as a hero who, like his son, is on a quest for self-knowledge. Achilles knows himself when he knows his place in the universe and chooses to stay and fight, spending most of his time willingly apart from society. Odysseus, however, spends most of his poem trying to get back to society while eschewing his identity. Beye says of Odysseus that he “is a man whose need to reinvent himself motivates his stoic determination to get home and resume the mantle of husband, father, squire as much as it does his notable artistry in creating new identities whenever he is asked who he is” (203). Odysseus’s multiplicity of identities may be more ubiquitous in the Odyssey than lessons on hospitality. He tells the Cyclops he is “No-man,” he is transformed into an old beggar by Athena; he creates a persona within that persona to test his servants. He even creates false identities to test Penelope and his own father at the close of the poem despite the fact he has already secured his kingdom. Clever, guileful Odysseus utilizes trickery and deception throughout to achieve his ends.

Twice, at crucial points in his journey, he is prevented from using his usual tactics, and both times Odysseus recovers his true identity and gains self-understanding. The first is his encounter with Tiresias in the Underworld, when he must acknowledge he needs wisdom and advice beyond his own ability to succeed. Odysseus’s second encounter with self-understanding is with the Phaecians, when he is directly asked the important question of identity, “who are you?” Having just wept at a song of the Trojan War, Odysseus can no longer hide his identity. Toohey comments that “[r]eliving the past forces him, first to disclose his identity, and second to emerge from the shell of self-pity, negativism, and self-interest caused by the loss of his fleet and his companions” (52). Like with Tiresias, Odysseus gets the assistance and reward necessary to complete his return home, but only after he abjures his false identities and guile and reveals himself with complete honesty. He already understands his universe of hospitality and proper social structure and enjoys mostly uninterrupted harmony with the gods on his journey. Self-knowledge, and his acceptance of it, is Odysseus’s transcendent path to success.

In different but equally important ways, Achilles and Odysseus as epic heroes successfully embrace the Western epic’s theme of transcendent understanding: Achilles learns the true nature of his society, his gods, and his place in the universe; Odysseus learns and accepts his identity and self-awareness, choosing mortality over isolated immortality, with all of its (and his) shortcomings. Epic heroes make choices, for good or bad, and face the consequences of those choices as representatives of all humanity, knowing that others do not have the transcendent heroic understanding to know what is necessary to live the full, heroic life. The Western ancient epic asks important questions about life, the value of mankind, and proper understanding of reality. These questions, like humanity itself, have not changed since the Homeric epic age. They are still relevant today. Babylon 5, the rebirth of the Western ancient epic for a contemporary audience, asks them again in a new way.

Works Cited In Part One

Beye, Charles Rowan. Ancient Epic Poetry: Homer, Apollonius, Virgil with a Chapter on the Gilgamesh Poems. Wauconda: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc., 2006.

Bloom, Harold. Where Shall Wisdom be Found? New York: Riverhead, 2004.

Bowra, C.M. “Some Characteristics of Literary Epic.” Virgil: A Collection of Critical Essays. Twentieth Century Views. Ed. Steele Commager. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1966.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 2nd Edition. Bollingen Series XVII. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1968, 1949.

Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. Chicago: U Chicago P, 1951.

—. The Odyssey. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Lattimore, Richmond. Introduction. The Iliad. By Homer. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1951.

Leithart, Peter J. Heroes of the City of Man: A Christian Guide to Select Ancient Literature. Moscow: Canon Press, 1999.

Murray, Gilbert. The Rise of the Greek Epic. 4th ed. New York: OUP, 1960.

Powell, Barry B. Homer. Blackwell Introductions to the Classical World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Redfield, James M. “Nature and Culture in the Iliad: Purification.” Modern Critical Interpretations: The Iliad. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Toohey, Peter. Reading Epic: An Introduction to the Ancient Narratives. London: Routledge, 1992.

Whitman, Cedric H. Homer and the Heroic Tradition. New York: Norton, 1958.

Wood, Michael. In Search of the Trojan War. Updated Ed. Berkley: U California P, 1996, 1985.

“… Babylon 5’s utilization and reinvention of the various components of the Western ancient epic genre.”

Fascinating! I’ll have to come back and finish reading this after I post my next Minbari Monday review.

Shira

LikeLike