Christopher Rush

“Is U2 still relevant?” Child, please.

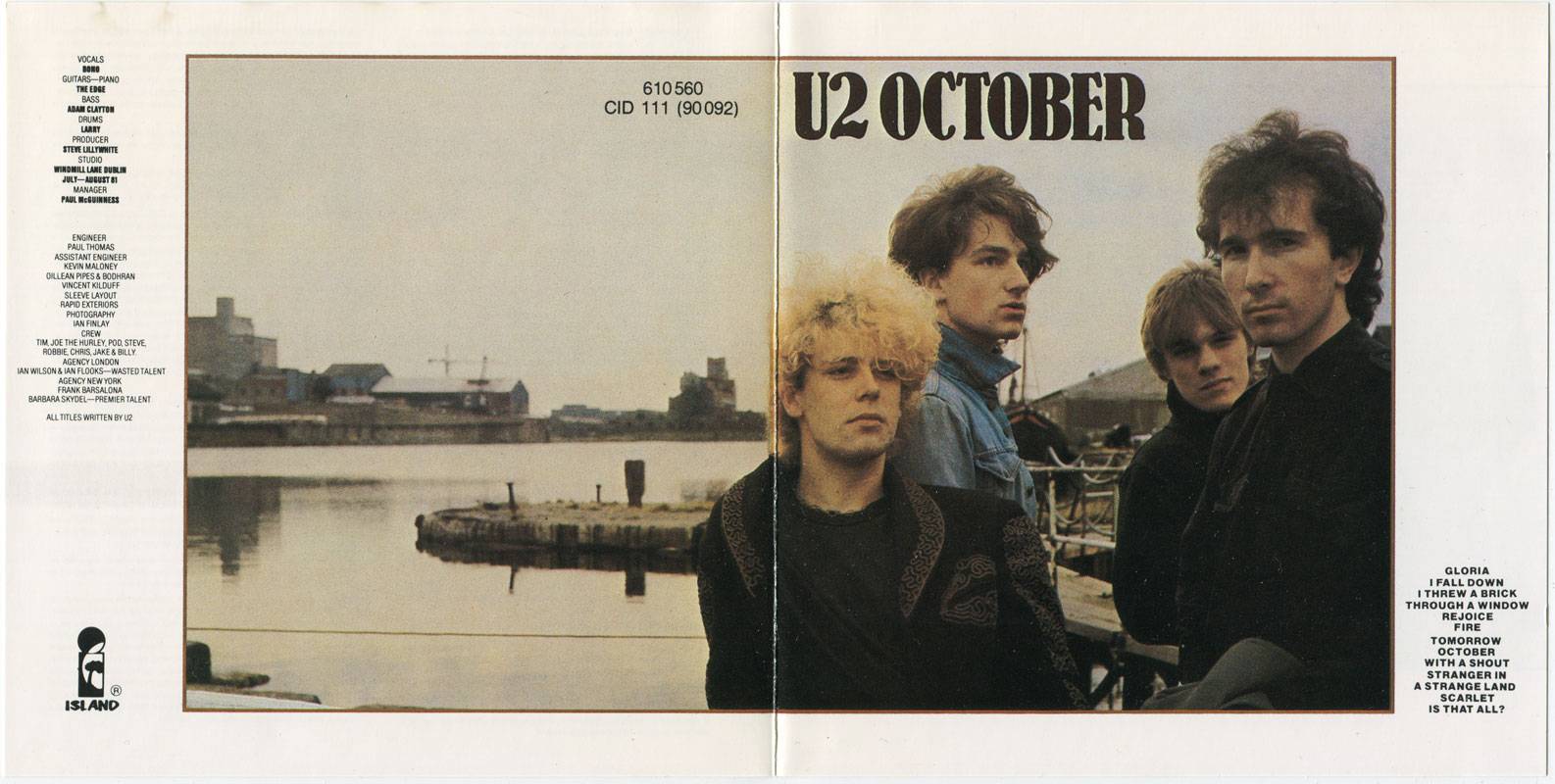

People are the worst. People today actually ask if U2 is still relevant. Based on their three most recent albums alone, it’s quite possible they are more relevant today than ever! Nothing in their output has become outmoded — nothing is dated (other than their hairstyles from the ’80s — but whose hasn’t?). Aung San Suu Kyi has been released from prison, but that doesn’t mean their campaign is yesterday’s news and tomorrow’s discount bin. U2 is one of the few bands with both real staying power and their original lineup still intact after over 30 years of work. Even though it’s possible they may actually be underrated as a whole, and all of their albums deserve continual presence before us, and even though we have just declared their most recent albums as key proof they are still relevant (more so than the question deserves), we should return to their second album, October, for a great example of how they have been relevant since the beginning, in part as well since it foreshadows many of the religious themes and concepts they have maintained throughout their career yet emphasized more overtly in their recent work.

“Gloria”

Few songs since the Enlightenment open an album with a more exultant, joyous mood than “Gloria” opens October. Some perhaps decry October because of the brevity and apparent simplicity of its lyrics. This is in part more understandable than most give the band credit, considering the adverse conditions under which the album was created (documentation of which is widely available and need not be rehashed here). As we have mentioned throughout the musical analytical career of Redeeming Pandora, “brevity and simplicity” are never deterrents to quality. More often, they are assets (if not integral components) to quality. Often the lyrics that seem “simple” are stylistically unadorned because they communicate the powerful passion the lyricist is laying bare for all to experience. (Admittedly, an overwhelming number of songs that look simple and sound simple are, in fact, simple, especially if accompanied by synthesized sounds, but this does not apply to “Gloria” or October … or ever in U2, really.)

“Gloria” is a straightforward mild lamentation of a man admitting before God and us despite his best efforts under his own mortal power he cannot succeed in life in any substantial way apart from God. Nothing he says apart from God is worth uttering or hearing, nothing he owns is worth owning unless it is used for the glory of God. Can anyone find anything wrong with these lyrics? Neither can I. I’m sure we know the Latin portion of the song, Gloria in te Domine / Gloria exultate” roughly translates into English as “Glory in you, Lord / Glory, exalt Him,” such that we are commanded to exalt God. Can one disagree? After the Adam Clayton slap bass solo, the rousing outro is among the best conclusions of any song anyone has ever done. The joyous mood and musical zeal combined with the command to exalt God is certainly rare, especially in what some call Christian musical circles. More often today one is given the impression the only time we are to be joyous is when thinking about what God has done or what we are allowed to enjoy or receive (either now or later), but hardly ever when singing about one’s responsibility or command to exalt God. U2 certainly sets a far more encouraging, positive tone than popular music provides today.

“I Fall Down”

As this article no doubt already intimates, I am incredulous when people cast (erroneous) aspersions upon U2 (an inanely “in” thing to do these days). Some of the unwarranted backlash against October, especially, appears to come in response to this second song, primarily because such people never take the appropriate time and energy to actually understand not only the actual content of the lyrics but actually also the actual meaning of said lyrics. These are the people who assume “faster is better,” and if something cannot be grasped in fifteen-second intervals (or even more tersely), such a concept is not worth grasping at all. History will of a certain categorize these people properly, but we should be observant, intelligent, and courageous enough presently to categorize them in our own day for who and what they are as well: people to whom no serious attention need ever be paid (the 21st-century equivalent of Alexander Pope’s “dunces”).

“I Fall Down” is a much more complex and relevant song than most people, as just indicated, credit it — and its relevance is unfortunately only increasing in potency, as the new Dunces continue to have their way in social, intellectual, political, academic, and aesthetic life. It is not just a raucous lament of one’s inability to actually ambulate to any specific or otherwise location without inevitably and unintentionally plunging into a prostrate position. Indeed, it is a plaintive appeal for solidity of identity and purpose. The parallels to Paul Simon’s “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” are uncanny (even more so since again no conscious awareness of them was present at the time both albums were selected for this investigation). Julie, the female protagonist of the song, expresses her dissatisfaction with life and her lack of enjoyable progress, pictured well by her acknowledged lack of connection with the natural world. This acknowledgement is made evident in a sort of flashback from her love John, who has apparently found her in some sort of stupor (it is unclear whether Julie has committed suicide or is just unresponsive — even in the nascence of their career, it is highly doubtful U2 would write about a suicide, especially on such an optimistic and otherwise joyful album). John comes to realize through the stark confrontation with Julie’s condition and self-assessment he, too, is not living a life worth living and is making no significant progress — not because life itself is intrinsically meaningless, but because he has heretofore attempted to live life solely in selfish terms, even while in a relationship with Julie. John, too, realizes life must be lived in community and for the benefit of others: when we live life for ourselves, we “fall down” and break ourselves in the attempt to live selfishly. We should be others minded: waking up when others wake up, falling down when others fall down, and living co-mutually. When seen accurately, the lyrics and musical progression of the song cannot be seriously faulted.

“I Threw a Brick Through a Window”

Continuing the theme of the importance of human connectivity and interactivity, “I Threw a Brick Through a Window” is far from what many consider the typical late ’70s-early ’80s Irish music scene dominated by punk rock such as from Bob Geldof’s The Boomtown Rats. It is not about rioting (though Larry Mullen Jr.’s drumming can evoke that somewhat), it is not about civil unrest or destruction of private property – it is about the need to escape isolation, escape individualism, and escape self-centeredness. The narrator has come to a self-realization all he has been doing (most likely for his entire life to this point) is talking to himself, and thus has not heard a word anyone else has said. This metaphorical representation of self-centeredness is just as appropriate today as it was when first offered at the onset of the Big ’80s. Similarly, all his effort, all his walking, has been for naught — his movement he mistook for progress, as so many do; he was so absorbed by self he walked into a window, mistaking it for a mirror (as we sometimes do, preferring to use it to see what we want to see, ourselves, instead of what we should be seeing — God’s creation). When he realizes the mirror is actually a window, he realizes, too, he has been “going nowhere.”

The sparse music of this song adds to its ethereal qualities — the whole thing is mildly reminiscent of Plato’s allegory of the cave in its evocation of sparseness. This sparseness is most evident in the lyrical bridge paralleling Jesus’s words to His disciples so often: “No one is blinder than he who will not see.” Now that he has eyes, he can see his predicament and his need for escape from his isolation and for community. This is a lesson we all need to learn, and the sooner we realize we are responsibility for not being able to “see” the truth of ourselves and our station, the sooner we can begin to live and rejoice.

“Rejoice”

Tempering the possible interpretation individuality is insignificant and only likeminded community is the path to salvation, Bono reminds us sometimes we all serve by standing and waiting. In a world that is tumbling down, and would-be heroes have delusions of grandeur (and some may have divine callings for worldwide significance and change, we should not doubt), the task for universal suffrage or world peace or cessation of hunger is too much for most of us to handle. Likewise, in the abundance of community, the individual and his responsibility to worship God and be who God has called him or her to be can easily be subsumed in the “good intentions” of collectivism. What is our response when the weight of the times confounds our activity and speech, when we don’t know what to do or say? The proper response comes from three of the best lines in the album: “I can’t change the world / But I can change the world in me / If I rejoice.” Sometimes it’s not about changing the external world but rather properly aligning our experience of it (not to indulge in too much subjectivity, mind you) — and the best way to do this is, of course, to rejoice. We don’t rejoice in the state of the world, obviously, and certainly not in our inability to solve its problems as if embracing chaos and diabolical anarchy were an underappreciated value. No, we rejoice in who God is, what He has done, what He will do, that He is in control, and who we are in Him. Authentic leisure indeed.

“Fire”

Continuing the lyrical motif of “falling” (the blending of ideas and lyrics on this album is remarkably insistent — I wonder sometimes if October would have been a lesser album had Bono’s lyrics not been stolen … not to imply God orchestrated a theft or anything … sheer speculation on my part), Bono brings the ideas of accurate self-awareness, inward conversion, and worship to a climax with the seemingly ambiguous “Fire.” The pervasive “fire” is an internal yearning, an irrepressible drive pursue this new life of worship and community while all around him the once-familiar universe tumbles into temporary disorder (while actually realigning properly for the first time in his experience of it). It truly is an unforgettable fire, which U2 elaborates on later in the album of that name (though it is supplemented with the band’s mid-’80s infatuation with American music and experience). I suspect if we took the time and energy to remember that fire we first experienced at our conversions Christianity and life would not seem so dull so frequently. It is a stunning end to the first half of the album, supported again by a sparse musical accompaniment appropriate for the intellectual engagement with the words but jarring to our complacent standards of what pop music should be. October as a whole is an unrelenting rejection of soulless musical and lyrical contrivances without descending into the inanities and banalities of the avant-garde (understood accurately in its derogatory sense).

“Tomorrow”

What was originally side two of the album begins with a much more somber mood. Bono has recounted several times without being aware of it at the time he was composing a song about his mother’s funeral. Melancholy and uncertainty dominate much of the song, both lyrically and musically. The Irish Uilleann pipes add a pathos to the song’s opening, setting the mood brilliantly. Eventually the uncertainty and unfamiliarity with the sorrow, the events of the funeral, the acclimation to loss are replaced by a growing dependency on God and a renewed strength and certainty. Ironically, this comes through questions not answers. “Who broke the window” (perhaps an indirect reference to “I Threw a Brick”?), “who broke down the door? / Who tore the curtain and who was He for?” The sudden transfer from seemingly mundane earthly concerns to the allusive-laden tearing of the curtain grabs the singer’s attention as it does ours. He knows who tore the curtain and how that act of destruction was the greatest act of restoration. It was the same God-Man who “healed the wounds” and “heals the scars.”

The asking of these questions leads not to vocalized answers, as intimated above, but a renewed comprehension of pre-existing understanding, leading to a growing enthusiastic expression of faith in God (a rekindling of the fire of conversion) coupled with a need for personal volitional action: opening the door (since Jesus stands outside knocking) “To the Lamb of God / To the love of He who made / The light to see / He’s coming back, He’s coming back / I believe it / Jesus coming.” If anyone doubted the intent of the album, or U2’s ontology as a “Christian band,” surely this song ends all doubt. Bono knows his mother is not coming back, but he knows Jesus is coming back — and he will be there with his mother again in some imminent tomorrow. Amen.

“October”

The eponymous track is, seemingly, the least representative of the album’s theme and temperament. Even so, it is a fitting transition from “Tomorrow” to “With a Shout,” though it’s possible it would have worked even better before “Tomorrow,” keeping the slower, somber music sections together (but it still works well here, as I said, once the feel of the second half of the album becomes more apparent). The song allows Dave Evans to take a break from his guitar and play the piano in what is certainly an atypical rock song. The piano solo is evocative of the barrenness of October, especially one experienced in Ireland or Iowa or other adjacent lots in the celestial neighborhood. As such, it is hard to describe in plainer terms: it is beautiful in a haunting way, but it does not try to be too beautiful, since it attempts (and attains) a sterility and timelessness reflecting the almost pessimistic lyrics. Initial listenings most likely lead one to suppose the “you” in the final line of the song is addressed to October itself, but taking the album as a whole (supplemented by knowledge of live performances), most likely the “you” is not an autumnal apostrophe but a worshipful address to God. True, October goes on while kingdoms rise and kingdoms fall, but so does God — it is not “Dover Beach,” and though the singer is apathetic toward the bareness of the trees, it is not out of pessimism and a lament about the absence of love in the world: Bono knows the trees will be reclothed in multifarious leaves again. Thus the song is actually quite representative of the album, predominantly in its sparse yet entrancing musical accompaniment and its atmosphere of despair and disillusionment redeemed at the close to one of worship and stability and the promise of future restoration.

“With a Shout (Jerusalem)”

“With a Shout (Jerusalem)” is an energetic complement to the interrogatory methods of renewed worship in “Tomorrow.” The second half of the album shows us to be a call-and-response mode, abetted by the disputatio-like lyrical elements of many of its songs. Having already found sufficient answers to the previous questions, Bono turns to the future with “where do we go from here?” with the only reasonable response considering the direction of the album: “To the side of a hill” where “blood was spilt” for the salvation of mankind — Jerusalem. The fire of worship has been rekindled to the point where not only is he now shouting about it, but also he wants to “go to the foot of the Messiah / To the foot of He who made me see / To the side of a hill where we were still / We were filled with our love.” Do we yearn for that?

“Stranger in a Strange Land”

Having made it to Jerusalem, the complementary tone and mood diminishes to contemporary disappointment combined with an odd disquiet. The title is likewise ambiguous: is the man to whom Bono is referring and singing the stranger? most likely not, since Bono is the one taking pictures, getting on a bus, sleeping on a floor, and writing a letter to a missed loved one — usually not the sort of activities one does in one’s own town or community, especially when joined with the plaintive “I wish you were here” chorus. The presence of the soldier likewise gives us the impression we are in a territory used to hostilities — most likely the Holy Land. It’s not the place now he thought it would be: it’s a strange land full of strangers and streets that are longer than they appear, alluding to the atmosphere of insecurity; even the natives appear to be strangers in a strange land. Most likely the guy about whom Bono is singing is correct: Bono is the one who should run — he doesn’t quite belong here, even with his rekindled fire of worship. It’s not the time, yet. Perhaps it could be applied to us a wayfaring Christians, but I’m not sure that would do credit to the song, even if the sentiment is similar. It’s a mysterious song, indeed.

“Scarlet”

One’s first impression of the song is it should be called “rejoice,” since that is the total of its lyrical output. On further reflection, however, such over-simplicity is beneath U2 even at this early stage in their career. Calling it “Scarlet” adds a momentous weight to the song: we rejoice because our scarlet sins are now turned white as snow. The music helps make this possibly the best song on the album, up there with “Horizons” and “Pretty Donna” — surpassing them, in fact. Delight in it forever.

“Is That All?”

The Edge wakes us from our reverie with a borrowing of the guitar riff from “Cry” (the original composer of the song is allowed to do that). Setting the stage thematically for War, U2 starts the transformation from their languorous worship album to their discontented social awareness album. Bono is not angry at God, but he’s not happy with Him either. What else is there? The questioning album finds time for one more question (repeated several times): “Is that all?” The real intent of the song and the question comes in the single time Bono elaborates: “Is that all You want from me?” Since he is angry, but not angry with God, Bono relates his growing discontent with the world: having seen the dilapidated condition of the Holy Land, he is still rejoicing in who God is, but the fire inside is now vivifying his social awareness — this can’t be all God wants from him. He must be here to do more.

No, It’s Not All

So is U2. 10 albums later (and counting), U2 has continued to be relevant and pertinent and a Christian band for better than most who have claimed those descriptions. Perhaps the lyrics and music of October are not as mature and rich as All That You Can’t Leave Behind, How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, or No Line on the Horizon (or even The Joshua Tree), but U2 made their second, most pressure-filled album a worship album, willing to alienate their new audience at the nascence of their career, overcoming difficulties few other artists have had to endure deserves far more attention and respect than it has received. Even in their perhaps unpolished state, the songs of October are as truly worshipful as any others in the history of music and Christianity. October is a forgotten gem and deserves our musical and spiritual attention.