Alice Minium

The Intervening Variable of Here and There

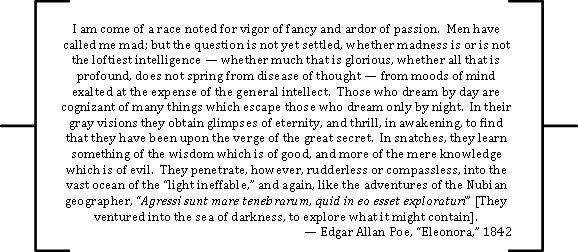

I write to you equipped with the story of a phenomenon of nature that I will share with you — it is a keyhole through which we may peer into the nature of the human psyche, the nature of our minds, the nature of art and aesthetics, the nature of reality, and the truth about transcending the ordinary limitations of human consciousness. It is a story that has cyclically endured throughout history, from the era of Aristotle to the drastically different era in which we live today. It is a truth indicative of human nature, and it bequeaths unto us an essential, largely untapped understanding of psychology. It is a circumstance of nature that it is vital for you to know, so that you may fully understand and know yourself. Understand the nature of your mind and why things are the way they are. Allow your thought processes to flow as fluid, flexible, and unrestrained, and allow yourself to be enlightened — but don’t get too lost in yourself. Don’t lose touch with the outside world. Think too much and you might go crazy … or maybe you already were. Maybe you know what it feels like. Maybe it’s always lingering in the back of your mind, in that dark corner into which you shove all the ugly things you cannot let the world see. You loathe the lurid black hole monster that has taken up residence in your brain like a tumor that is not a tumor, but a finger — a natural part of you from which you cannot escape. You loathe that black hole monster. But it is he who sweeps you up in his storm of intoxicating emotion that leaves beautiful, elegantly-crafted sonnets behind as the rubble. It is his provocation that inspires the intricate sketches that fill your notebook. You lose yourself in him, or perhaps you truly know yourself, or perhaps you truly know some things about life that people were just not supposed to know. There is so much in your head, and it secretes as art. Maybe creation is the only tactic you know to help you stay sane. Creation is dangerously similar to destruction.

Creativity is dangerously similar to madness.

As the human race, one thing we are most classically ignorant about is ourselves — and what it means to be a human. This is a topic on which most of us know very little. The relationship between creative genius and psychological instability is obvious, but not completely understood by us at all. We find ourselves in a chicken or the egg scenario. Here I will explain both that the chicken and egg are of the same nature and exactly how they are related to one another. I will be exploring many different theories upheld by many different individuals, but I will not present you with my own personal speculation as a means of hopefully convincing you this is true. The case I present here will rely fully and completely on logical deductions and factual evidence, including over ten clinical studies conducted by highly educated, highly reputed psychological experts. Ultimately, I encourage you to view the case I will present with objective, unpresuming eyes, and take from it what you will. The verdict is yours, but I will lay the evidence before you, encourage you to trace the validity of my arguments, and I stand here fully confident that you will reach the same conclusion that I did myself.

Personally, I find any standard dictionary to be habitually ineffective at encompassing the full essence of a concept with its overly formal and unspecific definitions. I have drawn upon a few other sources that will give us a more complete grasp of the meanings of the two essential words I would like to clearly define for you — the first is “creativity,” or, in other words, “creative genius.” Dr. C. E. Shalley, author of the psychological journal article “Effects of Productive Goals, Creativity Goals, and Personal Discretion on Individual Creativity,” defined creativity as “comprised of three major components: the required ability or expertise in a particular field, the innate or intrinsic motivation towards further exploration and development, and the cognitive processes to conceive and synthesize novel ideas.” Dr. Prentky, a fellow psychiatrist featured in the same psychiatric journal, elaborated by saying that “the main primary traits of creativity are fluency and flexibility of thinking, originality, redefinition, and elaboration.” When he says “elaboration,” he is referring to the unconscious process of expanding, embellishing, and simultaneously extrapolating a minute detail, usually one of the repressed psyche. There are many components to creativity, but these two definitions are an accurate basic skeleton on which we may rely. I will expand more on its nature, its features, and its origins when I present my major points of argument.

The second term that it is essential we define is “madness.” In this presentation, “madness” may be interchangeable with the term “psychological abnormalities” or “mental illness.” These words can mean many different things, so I would like to define them for you as clearly as possible. Dr. Caroline Koh from the National Institute of Education at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore is an expert at research on this topic, and she conjured up a very accurate and efficient explanation of these terms: “Madness is commonly described as an altered, abnormal, deviant state of mind or consciousness. The various forms of mental disorder are generally of two kinds. The first being the condition of neurosis, which describes the milder forms of mental disorders such as phobias, depressions, obsessions, compulsions and hypochondria. The second type of aberrant mental condition, psychosis, includes severe forms of mental illnesses, whereby the patient loses contact with reality and shows irrational and irresponsible behavior. Psychotic afflictions include delirium tremens, manic depressive disorder and schizophrenia.” In this presentation, we will be dealing more with psychotic afflictions than neurotic afflictions. However, both branches of psychological abnormalities are relevant and applicable to this case.

The relationship between creativity and psychopathology is tied together by artistic temperament, or, in other words, the moods, personality, and the way artists see the world. The artistic temperament, or condition of the artist, is what determines the psychological risk. You could call the artistic temperament the intervening variable of the relationship. An intervening variable is a hypothetical internal state that is used to explain the relationship between observed variables when they do not appear to have a definite connection, but simultaneously have no existence apart. In other words, we cannot say for sure whether creativity drives you crazy or if madness inspires you to be creative, but we can acknowledge the two are connected in a certain way based on the condition of the artistic temperament — if the artist is very mentally ill, she may also find herself bursting with creativity, or vice-versa, depending on other situational and circumstantial determinants in addition to her brain chemistry. The concept of an intervening variable is difficult to understand at first — a few other examples are intelligence, motivation, and intention, if that helps you to grasp the concept any better. Either way, the nature of this relationship will become clearer as we progress.

The correlation between madness and mental illness actually has a name: the Sylvia Plath effect. Psychologist Dr. James C. Kaufman coined this term in 2001 to refer to the phenomenon that creative writers suffer disproportionately from severe mental illness — more so than other types of writers, and more so than any other types of people. 2001 is fairly recent, but Kaufman was not the first to acknowledge this pattern in human psychology. Plutarch, Greek historian who lived from 46 to 120ad, described in his annals the Greek hero Archimedes from an intriguing perspective: “Archimedes was a combination of natural endowment, hard work, and divine inspiration — a personality which indulges in behavior which is distinctly unusual … in anyone else, we would be rather tempted to call it mad.” A fellow Greek, the great Aristotle, seemed to agree with Plutarch, writing, thousands of years ago, that “No great genius has ever been without some divine madness.” Almost two thousand years later, William Shakespeare echoes their tune: “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet are of imagination all compact.”

Enough with the quotations. It is simply a fact that a remarkably great percentage of our favorite innovative artistic geniuses have been afflicted with dark psychological pain. No expert on the topic will deny that. But now let’s get to the important part — why?

The first point of argument I will make is that the thought processes of exceptional artists and the mentally ill are similar in their operations and appear to be of a similar origin. I will prove this point by explaining the ideas of translogical thinking, conceptual overinclusiveness, Janusian thought processes, and homospatial thought processes. I will also touch on the influence of Dr. Albert Rothenberg, a psychiatrist who has published books on the topic and is considered an expert, and his colleague, Dr. Prentky. Finally, I will elaborate on a neurological study conducted at Harvard University and the University of Toronto in September 2003 that gives us a concrete biological basis for the connection of creativity to mental illness by testing something called Latent Inhibition. I will explain what Latent Inhibition is, how it works, and why it is incredibly significant to this case.

Dr. Prentky is one of many psychologists who has devoted his career to the understanding of this topic. Like the others, he postulates that the creative and the mad operate the same way on a neurological level. “Creativity and psychopathology share a similar origin,” he explains, “hence the biological link; that creative individuals and psychotics have some common personality traits and thinking reflecting a predisposition to psychosis. One of them is vague, highly intuitive thought processes, and imprecise and inappropriate speech.” Other common personality traits Prentky could have mentioned are peculiarity, introversion and an inclination to solitude, rejection of common cultural standards, a tolerance for irrationality, oft-disturbed moods, and the tendency to connect concepts in an unusual or unexpected manner.

Prentky declares that the most significant similarity between creatives and psychopaths is the loose, unrestricted boundaries of their thought processes. In other words, their perception of the world is not restrained by the limitations of cultural prejudices that intellectually suppress most people in any given period of time. You could say our creatives and psychopaths think “outside the box.” This could be for many reasons. Prominent among possible reasons is the fact that both of these people groups are comprised of individuals very different from their peers in very important ways. Even if they manage to have healthy social relationships, they are still, always, unlike everybody else in their psychological tendencies and the way they think (or, brain chemistry). When one feels like an outsider, one is not sucked up into the blindness afflicting everyone who has bought into the massive ruse. Many “crazy” artists in the past have had ideas way beyond their time (for one example, Leonardo da Vinci), because, abstinent from the habitual worldviews and mindless conditioning of their neighbors, they were more in touch with their inner consciousnesses and were capable of perceiving truth and concocting ideas that others could not comprehend and would have, in no way, dreamed of.

A more technical and precise term for this unique cognitive process they have in common is the term “translogical thinking.” Dr. Albert Rothenberg concluded from years of studies that this is definitely a psychological trait creatives and psychopaths share. Translogical thinking, as you may have deduced from its name, is a type of conceptualizing in which thinking processes transcend the ordinary mode of logical thinking. It involves two different thought processes, the first being the Janusian and the second being homospatial.

Janusian thinking is the process of combining paradoxical or antagonistic objects into a single entity. The homospatial process is, in Rothenberg’s words, “the essence of a good metaphor.” It involves superimposing or uniting multiple, discrete objects. These two processes constitute the method of creative thinking.

Although the creative and the psychopathological share these significant traits, obviously, there are characteristics to distinguish them from one another, and they are important to note. The fundamental difference between the creative and the mentally ill is the amount of control the individual has over his or her thought processes. The creative thinker is deliberate with her thought processes and is capable of deftly managing them. The psychotic thinker’s thought processes are sometimes inexplicably capricious, and she is incapable of controlling them; rather, they can easily overpower her at any time.

This might sound like a dramatic difference, and it is, but creatives and psychotics have more fundamental similarities than incompatibilities. Perhaps the most compelling chunk of evidence for this argument is the 2003 Harvard-Toronto study involving Latent Inhibition.

Latent Inhibition is defined (by the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology) as an animal’s unconscious capacity to screen from conscious awareness stimuli previously experienced as irrelevant to its needs. You are surrounded by a near-infinite amount of stimuli at all times, and there is no way you could consciously take notice of all of those things. Toronto Psychology Professor Jordan Peterson says, “This means that creative individuals remain in contact with the extra information constantly streaming in from the environment. The normal person classifies an object, and then forgets about it, even though that object is much more complex and interesting than he or she thinks. The creative person, by contrast, is always open to new possibilities.” The lower one’s LI is, the lower the ability to filter out irrelevant stimuli that interfere with focused thought processes. Consequently, the study showed, the lower one’s LI is, the more exceptional cognitive flexibility he or she displays, which leads to creative achievement. This study was groundbreaking, because, for the first time, the scientists were able to conclude that highly creatives and people suffering from psychotic illness both were characterized by very low levels of Latent Inhibition. Instead of connecting thoughts by basic logic, translogical thinking comes into play, and their neurons transmit signals to several other neurons people would not normally associate with one another, and they interpret information a different way.

The low level of Latent Inhibition is a concept that explains so much about the relationship between creativity and psychological abnormalities. Low LI can also be a characteristic of many forms of psychoses, including the early stages of schizophrenia. As one’s LI decreases, one may become fixated on meaningless ideas that feel almost religiously important, and one starts to slip away from reality.

Harvard researcher Shelley Carson thinks this makes perfect sense. “Scientists have wondered for a long time why madness and creativity seem linked. Many of us hypothesize that Latent Inhibition may be positive when combined with high intelligence and good working memory, but negative otherwise. It seems likely that low levels of Latent Inhibition and exceptional flexibility in thought could predispose to mental illness under some conditions and to creative accomplishments under others.”

Low LI could explain someone’s unique ability to discover something beautiful or spectacular within what most people consider unremarkable or potentially not even notice. It explains the ability to perceive the world with intensified acuity, the ability to transcend the mental or psychological inhibitions of a culture or time, and the ability to interpret stimuli differently to extract unique abstractions from seemingly dissimilar concepts.

Pablo Picasso, the legendary Spanish artist from the early twentieth century, preferred to live amongst chaos rather than a clean, organized home environment. He attested his reason to be that objects, when strewn about, appeared to have unusual visual relationships to each other. Picasso considered this artistically stimulating, as he did not perceive his surroundings in a typical manner — a clock as a clock, or a shoe as a shoe, but instead, his brain interpreted the objects as they appeared to him at that time in color and form, not as objects purely related to the functionality of his everyday life.

One of his most well-known sculptures, Bull’s Head, was an arrangement of the seat and handlebars of a bicycle that Picasso envisioned as shaped like the head of a bull. He was able to transcend his mind’s human instinct to interpret handlebars as “rods upon which you exert force in order to control the direction or maintain stability of a vehicle,” and uninhibited by that instinct he was able to see the essence of handlebars for what they were — elongated cylinders. Out of their ordinary context, he equated them to the existence of other similar objects, such as a bull’s horns. This example parallels the science behind a low Latent Inhibition and a high creative ability to see the world in an abnormal way.

Anne Sexton, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, practiced a similar albeit more abstract approach to transcending our natural instinct to overpass and not analyze stimuli that are not relevant for survival. Dr. Mary Baures, a psychologist who personally spent time with Sexton, recalls her methodology. “She taught us about images and metaphors. They were more powerful when you found connections between unlike things — a fist and a fetus, eyelids and riding boots, a tongue and a fish, flies and small black shoes, a girl curled like a snail. She showed us how to ‘image-monger’ by spewing out a torrent of metaphors in a process she called ‘storming the image.’ We would ‘unrepress’ by creating an unconscious for an object, like a can of Coke. The more we ‘unrepressed,’ the more rapid our associations became.”

Creativity is fundamentally dependent on communication with the inner psyche, although it is usually not conscious unrepressing. It brings you, in an artistic sense, to intelligence with your deepest, most unacknowledged, most primitive thoughts and feelings. Abandoning thought-association patterns ingrained by your environment simplifies and, in a way, purifies the way you experience the essence of a thing. Raw simplicity and awareness like this brings you back to the most basic, fundamental brain activity, to which every person can relate. The catharsis of connecting with and unrepressing these deeply repressed elements is what might make one feel “moved” by a particularly effective specimen of art or music.

This is also the idea behind the form of expressive psychotherapy called art therapy, in which the emotionally damaged patient will draw, paint, sculpt, write, or compose his own creative art to begin to heal and indirectly address the patient’s deeply repressed psychological tensions. Art therapy shows us that creative thought and emotional pain are deeply intertwined, which brings me to my second major argument.

Art and creativity require utterly consuming devotion and deeply personal contact with one’s primitive self (cravings, feelings, and emotions), which naturally puts one at the constant risk of walking the edge of sanity and insanity — because inner turmoils breed excellent, passionate art.

The twentieth-century poet John Berryman said it exceptionally well: “I do strongly feel that among the greatest pieces of luck for high achievement is ordeal. Certain great artists can make out without it, but mostly you need ordeal. My idea is this: The artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business. Beethoven’s deafness, Goya’s deafness, Milton’s blindness, that kind of thing. And I think that what happens in my poetic work in the future will probably largely depend not on my sitting calmly on my ass as I think, ‘Hmm, hmm, a long poem again? Hmm,’ but on kinds of other things short of senile dementia. At that point, I’m out, but short of that, I don’t know; I hope to be nearly crucified.”

This is a fact all creative individuals know very well. Tragedy results in excellent creative output. Even any amateur writer would admit that his writing is more poignant and powerful when he has been through an emotional disaster, or just had a bad day. Anne Sexton said, “Poetry led me by the hand out of madness.” Creativity is very healing for the mentally ill and is often a coping mechanism, but constant contact with one’s inner psyche and the total immersion in one’s work that is characteristic of both the creative and the psychopathological when involved in projects, produces an increased chance for one to slip out of touch with reality and into disillusion. Dr. Maureen Neihart elaborates, “Creativity involves a regression to more primitive mental processes, that to be creative requires a willingness to cross and recross the lines between rational and irrational thought. Inspiration always requires regression and dipping into irrationality in order to access unconscious symbols and thought.”

By nature, individuals in artistically creative professions must be more sensitive, unlike scientists, who work with logic. Art, on the other hand, is raw humanity. Creative individuals are more susceptible to a greater spectrum of emotions and perceptions, which makes them more susceptible to all emotions, especially the violent ones, because they are the ones that fuel artistic inspiration.

Skill is one part talent and ninety-nine parts blood, sweat, and tears. People who wholeheartedly devote their lives to creative endeavors might sacrifice just as much as people who devote their lives to Olympic sports. With creative work, it’s not obvious when you over-exert yourself or drive yourself crazy from isolation, pressure, and immersion in the fantasy world you are forced to inhabit. For child prodigies, or any adults who throw themselves into their work, it is easy to lose touch with the real world. If you are straining yourself mentally, your risk for danger is even more glaring than that of the Olympic athletes. If you damage yourself mentally, the consequences will be so much more detrimental. It’s all the same thing, except in this instance, the game is inside your head.

I would now like to refute an alleged objection to my thesis: the argument that creativity is a product of logic, and mental illness, by definition, is characterized by a lack of rationality.

At first glance, this argument looks like a reputable objection — until you stop and think about it. First of all, creativity does not come directly from logic. Logic leads to practicality, and if creativity was based on logic, it would be a function of practicality, which is incompatible with its primary concern being not survival, but innovation and aesthetics. Creativity is the ability to transcend the ordinary. Also, in complete contradiction to this point, it could be said that artistic creativity, in a way, actually stems from illogic — it is characterized by a disconnect with reality, and its lack of concern for logical things and greater interest in creating beauty serves no survival purpose whatsoever, which supposedly goes against our evolutionary nature as humans, which makes it perfectly compatible with mental illness.

Or, if you want to approach it in a slightly less brash manner, you could refute the statement “creativity is a product of logic” with the already affirmed statement “creativity is a product of translogic.” Therefore, even if mental illness does encompass irrationality, it also encompasses translogic, what is needed for creativity and what truly matters. You have to look at it from a broader perspective.

Another objection to my thesis that has been raised by many is this: “Not all creative prodigies are crazy, so there is not necessarily a correlation between creativity and being crazy.”

I would like to respond to this objection with the results of a scientific study performed by a certain Dr. J. Eysenck in the 1980s. After testing 21 males for a correlation between their level of creativity and their level of psychological abnormality, he found a mostly positive correlation, except not an exclusively positive correlation. Dr. Eysenck concluded that creativity and psychosis have a greater probability of being connected, but not in all circumstances.

“Psychosis” is the condition of being psychotic, but “psychotism” is the ability to potentially develop psychosis under certain situations. While psychosis and creativity were not always linked, psychotism and creativity absolutely were. Eysenck’s final word was that creative individuals are naturally predisposed to insanity, but they are not necessarily insane. Today this is known as “Eysenck’s P-factor.”

Obviously not all creative geniuses are mad, but that does not change the fact that a great percentage are, and the rest of them are at least genetically predisposed to it as a result of their exceptional creativity, whether it is active or not. Famous Impressionist Salvador Dalí knew this indeed when he said, and I quote, “The only difference between me and a madman is I am not mad.”

There is no consistent pattern of which one induces the other. Creativity and madness mutually reinforce each other, according to their natures as inherently related essences. Now, we have established that the processing styles of creative and psychotic brains are methodically similar and similar in origin, as understood by conceptual overinclusiveness, translogical thinking, and the evidence of the Latent Inhibition effect. We have also affirmed that the nature of art puts one in danger of intense emotional experiences, because that enhances art, so psychological vulnerability is and always will be an associated risk. I have refuted the objection that creativity and madness are not related because creativity is logical and madness is illogic by firstly explaining that creativity is not a product of logic, and by secondly explaining that creativity does not require logic but translogic. I also refuted the allegation that creativity and madness are not related because not all creative people are crazy, and not all crazy people are creative, so they cannot be intrinsically tied together. I shared the results of a scientific study in which they determined that creativity and madness, if you suffer from one, make you highly likely to be predisposed to the other, and that all the creative are not necessarily actively psychotic, but all of the creative are psychotismic — capable of developing psychosis under the right given circumstances. Therefore, the connection holds irrefutable and strong.

I would like to say I understand every aspect of this phenomenon, but the truth is, we actually only know so very little. And if these creative geniuses, these exceptional and elite, are of a higher consciousness than us average humans — who are we to judge the estate of their psychological health? We know so very little. But at most, we can cherish what we have learned about art, about suffering, and about humanity itself. And we can constantly strive to learn more. Not everyone gets to be exceptional, and you will never be the most beautiful poet, the most talented pianist, the most up-and-coming graffiti artist, and for a moment, that kills you inside. But, actually, maybe being a prodigy entails a whole lot more than I imagined. Marcel Proust said, “Everything great in the world is created by neurotics. They have composed our masterpieces, but we don’t consider what they have cost their creators in sleepless nights….”

The almost-prophetic whisper of the gifted novelist Janet Fitch reminds us, “Nobody becomes an artist unless they have to.” Yet each one of us secretly yearns to venture out into the sea of darkness, to explore what it might contain…

Be an artist. Fear no pain.

Bibliography

Barron, Frank. The Creative Personality: Akin to Madness, 1972.

de Manzano, O., et. al. “Thinking Outside a Less Intact Box: Thalamic Dopamine D2 Receptor Densities Are Negatively Related to Psychometric Creativity in Healthy Individuals.” PLoS, 2009.

Eysenck, H. J., Genius: The Natural History of Creativity. Cambridge: CUP, 1995.

Koh, Caroline. “Reviewing the Link between Creativity and Madness: A Postmodern Perspective.” National Institute of Education: Nanyang Technological University Singapore, 25 Sept. 2006. Web.

Marano, Hara Estroff. “Creativity and Mood: The Myth That Madness Heightens Creative Genius.” Psychology Today, 2007.

Neihart, Maureen. “Creativity, the Arts, and Madness.” Talentdevelop.com. Social and Emotional Development of Gifted Children, 1998. Web.

Prentky, R. A. “Creativity and Psychopathology — Gamboling at the seat of Madness,” in J. A. Glover, R. R. Ronning, and C. R. Reynolds, eds., Handbook of Creativity. New York: Plenum Press, 1989.

Richards R., et. al. “Creativity in Manic-depressives, Cyclothymes, Their Normal Relatives, and Control Subjects.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1988.

Rothenberg, A. Creativity and Madness — New Findings and Old Stereotypes. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1990.

Shalley, C. E. “Effects of Productive Goals, Creativity Goals, and Personal Discretion on Individual Creativity.” Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 76, 1991.