Christopher Rush

The Lamb Lies Down and Gabriel Bows Out

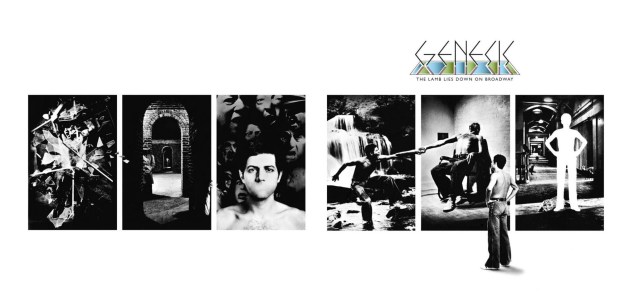

After the success of Selling England By the Pound, the follow-up album would be an important landmark in the direction of Genesis. Unfortunately, a variety of factors contributed to the end of the Golden Age of Genesis. For the first time, the creative process was changed: Peter Gabriel wrote most of the lyrics for Lamb apart from the band, as they wrote most of the music separately. When the two sides came together, the joining of lyrics and music was not as seamless as it had been before. Though some members of the band were somewhat relieved that the thematic content of Lamb was different from the mythical, mystical stuff that dominated so much of their previous albums (at least, for the most part), the collaboration process brought more frustration than camaraderie. Additionally, Gabriel was absent for much of the creative sessions, helping his wife during her debilitating pregnancy. Though this was admirable and certainly the right thing to do, it helped strain the relations of the band. Before the tour even began, Gabriel’s time with the band was technically over, though he did stay around long enough to complete the tour. This helped to further the rifts in the band, since Gabriel’s on-stage characters and costumes overshadowed, at least critically, the musicianship of the other band members. The lengthy Lamb Tour, in effect, finished off the Golden Age of Genesis. As he sings in “In the Cage,” the sweat (not sweet) has turned sour. They have come, in an odd, unfortunate way, full circle since From Genesis to Revelation.

In order to give The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway an appropriate tribute and analysis, frankly, we would need an entire issue of Redeeming Pandora solely for that purpose. If you thought “We Didn’t Start the Fire” takes a lot of footnotes to explicate, that is nothing compared to the voluminous amount of annotation necessary to delve into the mysteries and wonders of Gabriel’s fecund erudition. Lamb almost makes Joyce and Eliot seem obtuse. Without trying to sound proud, I don’t even understand it all myself, though I’m doing my best. For the sake of time, and an attempt to give some semblance of respect to what is rightly considered one of the best concept albums of all time, we shall offer an admittedly superficial exploration of some of the main ideas explored throughout the album. If time permits (and the journal continues), look for a more elaborate analysis of this monumental work in the future. Certainly more consideration needs to be given to the fantastic musical aspects of the album in addition to the lyrical narrative outline with which we will concern ourselves for now. In the meantime, listen to the album (many, many times) and read Gabriel’s story in the liner notes to tide you over until we meet again.

Part One

Lamb is a concept album, as mentioned before. The concept is much larger and expansive than a simple declarative sentence can encapsulate, but the basic story is the journey of self-discovery of Rael, the Imperial Aerosol Kid, Puerto Rican graffiti artist in New York City, though he thinks he is trying to save his brother John. Against that basic frame story, we meet mystical creatures like Keats’s Lamia, Lilywhite Lilith, and the Colony of Slippermen. Sprinkled throughout this mystical, mythical tale, Gabriel alludes to Wordsworth (“I wandered lonely as a cloud”), Motown (“I got sunshine”), and classical comedy (“Groucho with his movies trailing”), and just about everything else under the sun and subway.

The liner notes tell us “a lamb lies down. This lamb has nothing whatsoever to do with Rael, or any other lamb — it just lies down on Broadway.” Eh. Maybe. It might not be Van Eyck’s lamb, but it probably means something (everything in this album does, right?). Rael emerges from the steam and shadows, spray-painting R-A-E-L, as part of his attempt to make a name for himself. Discontent with his seemingly purposeless life, and that no one notices him and his work Rael wonders if it might be better to be a fly waiting to smash into a windshield. Soon, mists arise and Rael finds himself in a cage. His brother John appears but turns away and won’t help him. The cage disappears, and Rael spins down underground to see the Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging (mankind, obsessed with materialism and consumerism). He tries to save his brother John from turning into a lifeless advertisement, but suddenly he is back in New York City, at least he thinks he is. During his confusion, we get some of Rael’s backstory: his reform school days, his pyrotechnic tendencies, his time running with a gang, his commitment to being tough (pictured by shaving his hairy heart and cuddling a porcupine), and his first “romantic” encounter, which, despite the fine instruction he got from a book on how to succeed in such endeavors, ended in total failure. Romeo kissed by the book; Rael did everything else by it — neither ended well. These reflections come to a close; John is nowhere to be found.

Suddenly Rael is in a corridor with lambswool under his naked feet (far too many lamb references for it to mean nothing). One cannot hide from the present in one’s memory, Rael decides. He spots some people crawling along the carpet in the direction he must go, heeding the call: “We’ve got to get in to get out.” He follows the carpet crawlers (people, not bugs) up the stairs into a chamber of 32 doors. Looking at all of these doors, Rael ponders what he needs in life, deciding he needs “someone to believe in, someone to trust.” His whole life has been one of rebellion and individualism; it’s time for a change. It’s not about wealth: he can’t really trust either rich men or poor men. Countrymen seem more trustworthy than townmen, for diverse reasons. Every door seems to lead him back here, to a waiting room of fearful, solitary indecision. Priests, magicians, academics, and even his parents send him in different directions, “[b]ut nowhere feels quite right.” Rael decides that he’ll trust someone “who doesn’t shout what he’s found. / There’s no need to sell if you’re homeward bound.” Rael finally accepts he can’t live in fear anymore. He’s ready to trust — but whom?

Part Two

“The chamber was in confusion — all the voices shouting loud.” Rael sees Lilith, a pale, blind woman who needs Rael’s help as much as he needs hers. He leads her through the crowd into more darkness, and she leaves him to face his fear. “Two golden globes float into the room / And a blaze of white light fills the air.” Rael is blinded, tosses a stone in front of him in defense against an approaching whirring sound, glass breaks, the cavern collapses, and Rael is trapped in the rubble. This is where the album really gets weird.

Rael finds himself in the waiting room of the Supernatural Anaesthetist, who happens also to be a fine dancer. The gas he emits leads Rael down a long passageway until he enters a new magnificent chamber. “Inside, a long rose-water pool is shrouded by fine mist.” From the waters rise three Lamia, beautiful women with snake tails below the waist. Entranced by the anesthetic and their beauty, Rael “trusts in beauty blind” and enters the pool. Initially it seems the Lamia die and give their carcasses to Rael for food. Soon we discover it was all a trick. Rael glides along like the Lady of Shallott until the water around him “turns icy blue” and he arrives at the Colony of Slippermen.

The Slippermen are slimy, bumpy creatures — all victims of the Lamia’s ploy, and Rael is becoming one of them. The Slippermen point Rael in the direction of his brother John and the only cure for becoming a full Slipperman: castration by Doktor Dyper. Rael and John are reunited and quickly agree to the rather drastic “cure.” What’s left over after the operation is placed in “a yellow plastic shoobedoobe,” a storage tube, so what was removed can be used again in emergency situations. Suddenly, the dark cloud that first captured Rael in New York City returns, this time morphing into a giant Raven that steals his shoobedoobe. Rael goes after the Raven, but John abandons him again for the “safety” of the underworld. Rael is about to catch up with the Raven when he drops the tube into a river in a ravine. Rael watches it float away.

Rael decides to chase after it; just as he’s about to catch up with it, he sees the way out of this surreal underground prison: a window opens up back to New York City. Rael heads for the exit only to hear his brother cry for help down below in the ravine. Faced with the most important decision of his life, Rael plunges into action: abandoning the way back to freedom and home, he, like Huck Finn, risks staying “forever in this forsaken place” to rescue his brother. After an exciting and dangerous chase, Rael finally pulls his brother to safety … only to find he has not rescued John but Rael himself. The epilogue to the album, “it.,” intimates that “Rael” is a minor anagram of “Real.” Broadly speaking, the concept for this concept album is about living one’s life wisely and selflessly — but choose wisely, because the time to decide is now. Certainly some parallels exist to Pink Floyd’s The Wall, but enough differences exist for the two monumental albums to be considered separate entities, both of great value beyond diverse aesthetic experiences. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway reminds us of important truths about the brevity of life and the importance of making wise and selfless decisions in the time we are given.

“It’s Only Knock and Knowall, but I Like It”

Lest they be taken too seriously, though, Gabriel closes the album with the last of his Genesis-era multi-layered ironies: “Yes it’s only knock and knowall, but I like it.” A subtle Rolling Stones allusion conveys Gabriel’s mission (if I may use such a weighty word) on not only The Lamb but also his entire Genesis career: satire (knock) and erudition (knowall) have been combined to present serious ideas in an enjoyable musical medium, combining great lyrics for slow, moving emotional songs and lengthy epic-like narratives (both apocalyptic and diverting) with masterful musicianship (far too often overlooked at the time and even today). The album and Peter Gabriel’s tenure with the greatest progressive rock band of all time fade out, putting a knowing smile on our faces. He wouldn’t have it any other way.

With Peter Gabriel’s departure from the group, the course of Genesis took a major turn to survive … but survive it did. Like M*A*S*H had to adapt to the departures of Henry Blake and Trapper John, Genesis adapted (as it already had, with its early line-up changes before the classic lineup) for a new time and a new direction. After a lengthy search and no suitable replacement found for Gabriel, Phil Collins became the official frontman of the band, and the rest, as they say, is history. The next two albums, A Trick of the Tail (one of my favorites) and Wind and Wuthering (influenced by Wuthering Heights), continued the concept album approach for which classic Genesis is so noted. It was not until Steve Hackett’s departure before …And Then There Were Three in 1978 that Genesis began to fully morph away from the king of progressive rock into the radio-friendly creator of pop rock smash hit singles in the 1980s many people think of when they hear the band’s name.

Hopefully this brief survey of the Peter Gabriel era of Genesis has inspired you to go back to the band’s progressive rock roots and hear for yourself (perhaps not for the first time) the creative beginnings of the band before it was defined by “Invisible Touch.” Genesis is one of the most enjoyable and moving bands (lyrically and musically) of the modern musical era, with a history far richer than you may have known. Start from the beginning, and work your way to the end. And then do it again. You will be glad you did.