Christopher Rush

Those Eggs are Now Scrambled

Fresh from the success of the greatness of “Supper’s Ready” and Foxtrot, Genesis was poised to create their most successful album (according to certain systems of measurement) with the nonpareil Selling England By the Pound: at once a culmination of the pastoral motifs and ideas as far back as Trespass and a full maturation of the band’s musical abilities. I have admitted already Selling England By the Pound is my favorite Genesis album; hopefully that does not hamper your desire to listen to it or any other Genesis albums. Some of the nostalgia factor may be in evidence here, not only in the compositions by the band, but also in the universal recognition of the quality of the album, since this is the last typical Gabriel-era Genesis album, considering the unusual nature of his last effort, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. Though it seems they did not know at the time this was to be their last such classic album, enough heart and soul are poured into every song on this album to make their lack of prescience irrelevant. Much more politically satirical than they’ve been before, Selling England By the Pound is truly Genesis at its best.

“Dancing with the Moonlit Knight”

Though this is the last “typical” Gabriel-Genesis album (by which I mean the last album driven by epic narrative songs of radio-unfriendly length), it begins differently than all the others: with the voice of Peter Gabriel, a capella, singing/calling “‘Can you tell me where my country lies?’ / said the unifaun to his true love’s eyes.” From the first we are brought into a midsummer-night’s dream-like world of political satire, mythical beasts, and economic uncertainty. “‘It lies with me!’ cried the Queen of Maybe /— for her merchandise, he traded in his prize.” England is resting with the Queen of Maybe, uncertain where it is going, perhaps forgotten what it is and has been. The Wordsworthian assault on trading one’s prize for the merchandise of Maybe echoes the poet’s searing line “We have given our hearts away — a sordid boon” too much to be ignored (except by those Gabriel is satirizing). Despite the Elizabethan/idyllic music that begins to accompany Gabriel here, before the end of the first stanza of the album we are confronted with a pessimism even sadder (despite its much smaller scope) than the overpowering sorrow of “Watcher of the Skies” — perhaps because the music is so simple and soft the pathos is even more palpable. Sic transit exordium.

Immediately the scene shifts to another Genesis prototypical British scene: “‘Paper late!’ cried a voice in the crowd. / ‘Old man dies!’ The note he left was signed / ‘Old Father Thames’ — it seems he’s drowned; / selling England by the pound.” Newsies hawk their papes, youth and age continue their cycles, the water flows, and England fades into the twilight — if nothing is done to stop the acceptance of life just existing, sacrificing the important, the beautiful, on the altars of productivity, technology, and utility. It’s not right to make money off stories of people in unfortunate circumstances — by doing so, we are selling our own dignity. A culture with too much license start to consider themselves “Citizens of Hope and Glory,” and as “Time goes by” they think “it’s ‘the time of your life.’” This sort of overly-simplistic thinking meets with appropriate caution: “Easy now, sit you down. / Chewing through your Wimpy dreams, / they eat without a sound; / digesting England by the pound.” Life is not about having enough to get by, enough to enjoy for the day — enough food for today cannot be the standard for “the time of your life,” in part because it is too self-centered a perspective to be genuinely good. The “Wimpy dreams” is an allusion both to the Wimpy fast-food chain in the United Kingdom as well as the George Wimpey housing company for dream homes.

The change of tune at this point makes for a good bridge between the early musical motifs and the clangorous (but in a good way) chorus to come. In this bridge, Gabriel expresses the conflicting (and both erroneous) perspectives on what makes “the time of your life.” “Young man says ‘you are what you eat’ — eat well. / Old man says ‘you are what you wear’ — wear well.” Again the point is made that immaturity believes the only thing important in life is to enjoy the physical sensations of the moment; if bodily desires are satiated, nothing else is important for life is transitory and ephemeral — so says invincible youth. Old age, conversely, believes the good life is about one’s status in society, evidenced a great deal by one’s appearance, particularly by the name-brand apparel one wears. The mediating voice neither rejects nor approbates either point: instead, Gabriel simply enjoins the audience to do both: eat well and wear well — neither is “the right answer,” but neither are they bad advice as component parts of “the time of your life” as it truly is in relation to others and the well-being of society as a whole. Beyond intake and appearance, a more crucial factor is knowing who you are or “what you are,” not placing as much importance on what others think or say, “bursting your belt that is your homemade sham.”

The chorus is a rousing return to the multi-layered aspect of this opening song, back to the metaphorical characters framing the counter-point of typical British life: “The Captain leads his dance right on through the night — join the dance… / Follow on! Till the Grail sun sets in the mold. / Follow on! Till the Grail is cold. / Dancing out with the Moonlit Knight, / Knights of the Green Shield stamp and shout.” Britannia, the Moonlit Knight takes us on a cosmic turn to the past and present of merry old England. The Green Shield stamp is a subtle allusion to the Green Shield Trading Stamp Company designed to encourage consumerism by enabling the purchase of gifts through the stamp system (a kind of precursor to the credit card rewards programs so popular today).

Speaking of credit cards, after the fast-paced musical interlude, Gabriel uses a different voice for the slightly menacing carnival-barker bridge: “There’s a fat old lady outside the saloon; / laying out the credit cards she plays Fortune. / The deck is uneven right from the start; / and all of their hands are playing a part.” The juxtaposition of tarot cards and credit cards is even more applicable today than it was forty years ago, as we are ever-increasingly saturated with the farcical notions of credit. The best credit score is actually 0, since it means you don’t owe anyone anything and thus are not a servant to the lender. Perhaps the sub-zero prime mortgage crisis could have been averted had more people heeded Genesis’s warning that Fortune is not based on credit any more than a crystal ball can tell your future: the deck of credit cards is uneven, not in your favor. Paying with money that does not exist is not a sign of wealth — it is a sign of folly. The multiple meanings of “hands” after that is another example of Gabriel’s fully-mature lyrical skill. In few words he has brought several layers of meaning through his symbols.

From that mystical scene we return to the chorus, blending, like a merry-go-round, clanging band music and medieval/pastoral animal imagery: “You play the hobbyhorse, / I’ll play the fool. We’ll tease the bull / ringing round and loud, loud and round.” The album is now a game, lightening the mood while subverting our attention away from the political and social satire that will undoubtedly continue. “Follow on! With a twist of the world we go. / Follow on! Till the gold is cold. / Dancing out with the Moonlit Knight, / Knights of the Green Shield stamp and shout.” Intentionally our views of the world will be twisted and the gold will cool (so much currency talk in this song) and no more coinage to go in the pay slots. The music then mirrors this predicted winding down; after another rousing and different musical break, the momentum fades and decrescendos into another musical box-like cadence, like stars twinkling out in the ending night.

“I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe)”

The fading guitar sprinkles meld into Tony Banks’s Mellotron hum imitating a lawnmower. “I Know What I Like” is Genesis’s first commercial single success, essentially the only one of Gabriel’s career as their front man. Though Phil Collins’s turn in the years ahead would see the band’s shift to a more radio- and commercial-friendly incarnation with many single hits, “I Know What I Like” helped form the nascence of that forthcoming mutation, so those who “blame” Genesis’s transformation on Phil Collins ignore the earlier evidences of that progression. This song remained popular in the band’s live concert repertoire, eventually becoming the framework to the enjoyable lengthy medley of tunes from the Gabriel and early Collins years later in the band’s career.

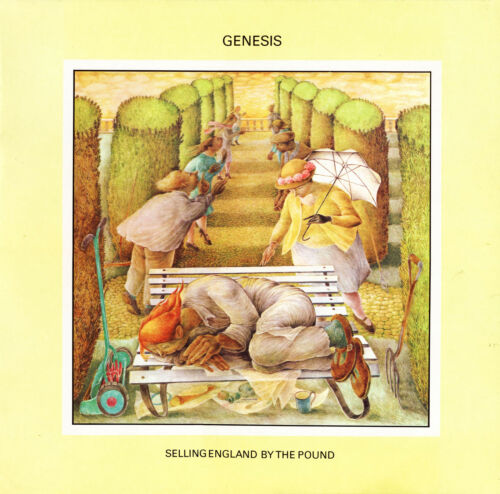

Like so many others in their early canon, this song is a frame story. The lawn mower lies down for a lunchtime nap, recalling the conversations he overhears both during his lunch break and, most likely, throughout his workday as a whole. The song is based on the cover painting The Dream by Betty Swanwick (the band had her add the lawn mower machine to it; it was not in the original version of the painting).

The chorus, preceded by the utilitarian motto of the lawn mower “Keep them mowing blades sharp…” is the most recognizable couplet to the passive Genesis fan from the Gabriel era: “I know what I like, and I like what I know; / getting better in your wardrobe, stepping one beyond your show.” It’s a rather occluded couplet: why the lawn mower knows what it is in the wardrobe of the people whose lawns he mows is never explained. If he’s spending so much time observing their outfits, can he really be that good of a lawn mower, ever distracted by his customers’ speech and apparel? Being unfamiliar with colloquial British expressions, I am incapable of sussing out what “stepping one beyond your show” truly means; I suspect it has something to do with the ever-increasing appearance of affluence of the members in the neighborhood, but I am completely open to correction.

Further in the lawn mower’s lunchtime reflections, he recalls segments of a previous phone conversation with Mr. Farmer: “Listen, son, you’re wasting time; there’s a future for you / in the fire escape trade. Come up to town!” That the lawn mower overhears so many different snippets of conversation throughout his workday indicates he is a popular lawn mower (despite the contradictions indicated above). This is further demonstrated by the phone call asking him to make a better life for himself in what is suggested to be a more lucrative, and thus better, position in what only the British would call “the fire escape trade.” Despite the seeming advantages in such a movement, the anonymous lawn mower rejects such an offer, after recalling an even older memory of advice he had received in his youth: “Gambling only pays when you’re winning.” Though he may consider himself “a failure,” and should logically jump at the chance for a better job, he considers the fire escape trade a gamble that will not pay off, so he resigns himself to his present position. His life as a lawn mower will forever be recognized, failure or not, by the way he walks. The unusual Eastern beat and melody fades out of this unusual, quirky song slightly reminiscent of “Harold the Barrel” but much more humorous and lighthearted.

“Firth of Fifth”

A play on the common name of the River Forth in Scotland (the “Firth of Forth”), “Firth of Fifth” is about as quintessential “Genesis sound” as any one of their numbers in the Gabriel era gets. Here, the full maturity of the band’s musical skills is in evidence from the downbeat. Tony Banks’s introduction surpasses even “Watcher of the Skies” in proficiency and downright impressiveness. The mixture of 2/4, 13/16, and 15/16 time signatures reminds us piano dilettantes what the instrument is capable of in expert hands. Additionally, Steve Hackett’s guitar work and Peter Gabriel’s flute work complement the complex and driving melodic lines throughout all nine minutes of this mighty piece.

Lyrically, the song has not aged as well as others in the Gabriel era, but it is better than most seem to recall. It is a return to the over-ambiguous lyrics of the very early days, admittedly, but it still has enough coherent connotations to make its mythical subtext enjoyable and believable. Deeper assessment of the words discovers that it can be read as a mixture of Psalm 23, Isaiah 53, and John 10 (with a sprinkling of Romans 1): the people of the world are sheep, who, despite the obvious signs and demarcations in place from the foundations of the universe, refuse to travel the path to freedom. The sheep are overcome by many dangers in nature and myth (Sirens, Neptune), until the great Shepherd returns to save them fully. The most coherent aspects of the lyrics are the beginning and end of the words, true. The middle sections are rather opaque and should probably be taken as furtive aspects of the impressive (if not rationally comprehensible) creative accomplishments of the Shepherd Himself. As a whole, this song can be one of the most enjoyable of Genesis’s entire output, despite the elusive lyrics at times — their progressive rock skills musically overpower any confusion about the words. The words that do make sense are Biblically sound and encouraging, despite the seemingly pessimistic final couplet: “The sands of time were eroded by / The river of constant change.” Consider it another grouping of words going more for the aural effect than the rational cohesion of their denotative meaning, especially with the rest of the song. By themselves, they are akin to the apocalyptic language of “Watcher of the Sky,” but almost don’t seem to fit fully in this song, which may account in part why Banks doesn’t consider this lyric with much fondness. They are still comparatively young lads at the apex of their initial popularity, after all, and the song, as mentioned above, as a whole is great.

“More Fool Me”

The second Genesis song led by Phil Collins (the first, as you recall, was “For Absent Friends” from Nursery Cryme), “More Fool Me” is the sparsest number on the album with only Collins’s vocals and Mike Rutherford’s acoustic guitar. It is a highly enjoyable change of pace on the album (not that the other songs aren’t enjoyable), especially coming before the lengthy British satire “The Battle of Epping Forest.” It is a relaxing, folk-like ballad about an optimistic young man who, with a self-effacing humor, believes that everything with his girlfriend who has just walked out on him will end up all right. It’s probably the quietest of the quiet Gabriel-era songs, especially at the beginning. It needs no further comment: listen and enjoy.

“The Battle of Epping Forest”

“Taken from a news story concerning two rival gangs fighting over East-End Protection rights,” according to the liner notes, “Epping Forest” is a mixture of “Giant Hogweed” and “Harold the Barrel,” with the medieval-modern British satirical tone pervasive throughout the present album. The album as a whole oscillates between border-line cynicism and tongue-in-cheek optimism. “Epping Forest” leans more toward the latter, until the climax of the song. The song is overtly self-explanatory, even for social criticism. It certainly doesn’t need the extensive footnoting that T.S. Eliot or even Jonathan Swift requires. It’s a lengthy song and some may justifiably conjecture that it is too lengthy — a lot of words are sung by Gabriel in these almost twelve minutes. The quirkiness of the song allows Gabriel to use a variety of personas during the different combat scenes, as well as the neighborhood episodes. The comedic tensions of gangs fighting to “protect” the poor, with the multiple meanings of “protection” throughout the song, are among the highlights of the lengthy number. The diverse musical motifs and tempos also provide good variety, without which the song would become tedious (some may say “even more tedious,” but that’s unnecessarily harsh).

The various scenes display the album’s blending of modern and antique England. The “Robin Hood” scene is the cleverest lyrically; the Reverend looking for used furniture following the “Beautiful Chest” sign leads to near Benny Hill-like comedy, though Gabriel rescues it (to a degree) from sheer objectification. The musical breaks during the different vocal sections are further signs of the band’s musical skill. Were “Epping Forest” not on the same album as “Firth of Fifth” and “Cinema Show,” it would probably have achieved more notoriety. The ending is a lyrical pyrrhic victory matched by the music: the story is unsure who wins the fight (since both sides essentially wipe each other out), and the ambiguous and uncertain melodic irresolution demonstrates that well. This is one of the better unities of the lyrics and music during the song; it isn’t always so appropriately blended. Altogether, it’s a clever song that occasionally (and only then briefly) suffers from the weight of its own vast and sundry intentions.

“After the Ordeal”

I do not understand why Tony Banks and Peter Gabriel were against including this song on the album; I can understand why Steve Hackett would eventually quit, since the other band mates seemed to consider his compositions (such as this one) so poor. Did they forget about “Horizons”? This is a great song, doubly so since it is a completely believable transition from the end of “Epping Forest” to “Cinema Show.” Without this, the transition would be fine, but with it, the album has another lyric-free achievement celebrating their musical greatness. Gabriel even gets some keen moments of flute solo work in. Regardless of the band’s derisive assessment of it, “After the Ordeal” is an enjoyable, cathartic musical number.

“The Cinema Show”

With a harpsichord-like introduction recalling to mind strains of “The Musical Box,” Genesis begins the last (and arguably best) of its Gabriel-era epic numbers. The sweet, dulcet tones supporting the gentle lyrics at the start of the song may even surpass the beginning of “Supper’s Ready” (nothing surpasses its ending, of course). The satire here is devoid of cynicism, which is a bit of a relief after the lengthy “Epping Forest.” The clever multi-layered diction is here in full, and the names of the characters evoke both Shakespeare and e.e. cummings: Juliet and Romeo are prototypical Britishers. Gabriel’s impressive but all-too rare synesthesia ability returns as well: “Home from work our Juliet / Clears her morning meal. / She dabs her skin with pretty smells / Concealing to appeal.” Gabriel couples both his sensory word play (skin is usually about touch, but here it’s about the source of her perfume) with his clever paradoxes as seen with the battle to preserve peace in “Epping Forest” (“concealing to appeal,” certainly one of the most intelligent lines in all of Gabriel’s tenure with the band). “‘I will make my bed,’ / She said, but turned to go. / Can she be late for her Cinema show? / Cinema show?” Juliet, despite being a lovely, typical girl (in no derogatory way), has enough procrastination in her to make her even more appealing. Who wouldn’t want to hang with a girl more concerned with enjoying genuine leisure than incessant cleanliness, willing to put the bed making off until after a movie?

The Romeo of “Cinema Show” is like Shakespeare’s Romeo, once he has seen Juliet at the Capulet party at the end of act 1. This song, in fact, could easily be a musical version of an understood scene between acts one and two, with modern accoutrement. The contrast of Juliet waiting to make her bed (as in, put the sheets back in order) because she’ll just get back in it by herself after the movie, with Romeo’s desire to make his bed with Juliet (as in, have Juliet in it, too), is yet another great example of Gabriel’s subtle lyrical skill (though Banks and Rutherford wrote the song, admittedly). Describing Romeo as a “weekend millionaire” is a trenchant commentary on the dating scene. Yes, Juliet is a part of it with her “concealing to appeal” perfume, but we have no reason to believe she is looking to spend her post-motion-picture evening with anyone or anywhere but her yet-to-be-made bed. Gabriel’s final observatory question, “Can he fail, armed with his chocolate surprise?” is a fitting end to the gentle send-up of this aspect of contemporary British life (a scene still relevant today, even in America, much more so than “Epping Forest”). How could a typical lothario possibly not succeed by offering a woman chocolates, a completely original idea!

The music picks up speed and motion, and Gabriel changes the scope of the exploration of modern love (in Elizabethan garb — or the other way around, if you prefer). From Shakespeare we travel further back to Ovid. Much has been said of the influence of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land — no doubt Banks and Rutherford (and the others) read it in school growing up in 1950s-60s England, in addition to the classics they must have read in public school, perhaps good old Charterhouse School, where Genesis was formed. Even so, the lyrics are not intended to be as obfuscatory as Modern Eliot was. Ovid’s Tiresias is helpful enough to understand the gist of what Gabriel is saying. (If you have not read either The Waste Land or Metamorphoses, you should do so after finishing this journal.)

Father Tiresias, we are told by all sources, spent time as both a man and a woman: “‘I have crossed between the poles, for me there’s no mystery.’” For this experiential perspective on the differences between the genders he lost his eyesight, according to some. What is not so clear in this song, we are told by some critical sources, is the meaning of Tiresias’ encoded language next. “Once a man, like the sea I raged. / Once a woman, like the earth I gave. / And there is in fact more earth than sea.” At first hearing it may seem Tiresias is commenting on the sheer population difference between men and women in the world: women outnumber men on the earth. (Not even Tiresias would literally think the globe consisted of more land than sea, would he?) However, the meaning, we are told, is something different: “there is in fact more earth than sea” means that women enjoy making love more than men do, on a physical level at least. If that’s true (the right interpretation of Tiresias’ words, not necessarily the authenticity of the interpretation), the fact Juliet is not interested in any physical conclusion to the cinema date with Romeo who is very much looking forward to such an encounter, makes the tale full of humorous and unexpected twists and turns.

The other great aspect of this final epic number from Gabriel’s tenure as Genesis’s front man and flautist begins at the seven-minute mark. The final four instrumental minutes of the number begin with one of Banks’s finest melodic/solo lines. Without trying to sound too effusive, the line is soaring, evocative, and uplifting. The rhythm section soon buttresses Banks’s work with a catchy, driving, syncopated support. Eventually, the motif works its way through enough variations to everyone’s satisfaction, winding down as so many of Genesis’s lengthy numbers do, returning from its 7/8 beat to its original 4/4 time. The melodic line returns to a variation of “Dancing with the Moonlit Knight,” bookending the album brilliantly and blending into the final epilogue number. Since “Aisle of Plenty” was not played on tour, the live concert version of “Cinema Show” received a new, self-contained ending, just as good in its own way.

“Aisle of Plenty”

As a reprise of “Moonlit Knight,” “Aisle of Plenty” is clearly a coda for Selling England By the Pound, uniting the album as one of the best concept albums of the progressive rock genre. In fewer than one hundred seconds, Gabriel demonstrates his uncanny lyrical ability to pun and satirize in rapid fashion. It’s doubtful Tess is the Queen of Maybe, thus making the connection to the first song musical and thematic, not directly lyrical/character-driven. The idea of being lost away from home is clearly a thematic premise throughout the album.

“‘I don’t belong here,’ said old Tessa out loud. / ‘Easy, love, there’s the Safe Way Home.’ / — thankful for her Fine Fair discount, Tess Co-operates / Still alone in o-hell-o / — see the deadly nightshade grow.” Gabriel sings of three different grocery store chains (Safeway, Fine Fair, and Tesco) as well as the large Co-op (The Co-operative Group) that dominates British retail life. Though Safeway and Fine Fare do not exist anymore, Tesco is the second-largest profitable grocery chain in the world (after Wal-Mart). I can attest to the reasonable prices and fine quality of their goods (the last time I had some shepherd’s pie from Tesco, it was quite tasty and filling and cost only 69p, VAT). The title of the song is another example of Gabriel’s multi-layered diction, though this time the pun is more overt. The “sceptered isle” of England, having traded in its prize for the merchandise of the Queen of Maybe has become the grocery store “aisle” of cloying affluence. The seeming pessimism is furthered by the final lines, “Still alone in o-hell-o / — see the deadly nightshade grow.” The nightshade, kin to the essential foodstuffs of British living (potatoes, tomatoes, and eggplants), is the poisonous member of that family, which is slowly and maliciously taking over (somewhat reminiscent of “Giant Hogweed” two albums before). Also, the nightshade could be another double-meaning reference, in that Tess, satisfied that she has her goods and safety, closes the nightshade on her window to the dangers and economic/social factors in turmoil outside. If Tess represents mainstream England (and what is more “mainstream” than commercial grocery store chains), it has clearly not learned its lesson. At the dawn of a new day, the hawkers return in full force:

ENGLISH RIBS OF BEEF CUT DOWN TO 47p LB

PEEK FREANS FAMILY ASSORTED FROM 17 ½p to 12p

FAIRY LIQUID GIANT — SLASHED FROM 20p TO 17 ½p

TABLE JELLYS AT 4p EACH

ANCHOR BUTTER DOWN TO 11p FOR A ½LB

BIRD’S EYE DAIRY CREAM SPONGE ON OFFER THIS WEEK.

Peek Freans was a biscuit and related-confectionary brand, now subsumed under United Biscuits and Kraft Foods. Fairy Liquid is a Procter & Gamble washing-up liquid now genericized (like Xerox and Kleenex) to mean any liquid washing-up product in the United Kingdom. Anchor is a New Zealand dairy company popular in the United Kingdom (and other places). Bird’s Eye is the international frozen foods magnate, of course (though I’m not sure what a “dairy cream sponge” is).

“It’s Scrambled Eggs”

“It’s Scrambled Eggs” are the final words from the liner notes. We must go on living, but we can’t be solely concerned about the price of living in our own little communities, as if our own material needs are the only causes worth investigating and fighting for. Selling England By the Pound does not offer many direct solutions to any of these problems, but it does give us strong reminders of the dangers of living only for ourselves. The music of the album is among the best of Genesis’s career; the lyrics likewise display the great skill (for the most part) of the band’s mature output. Collectively, the album is a phenomenal work.

With this album, Genesis clearly eradicates any doubts about their greatness not only as a progressive rock band but as musicians and writers at large. The unity of the album is stupendous, maintaining and morphing its satirical needs brilliantly throughout a variety of subjects. As the last of the typical Gabriel-era albums, Selling England By the Pound proves that by abandoning the limiting restraints of their initial management, Genesis could incorporate myth, satire, literature, and imagination into something astounding. Though they may have burned up their reserve of epic music, scrambling all their lengthy creativity eggs, it was well worth it. With a combination of pungent social satire, classical allusions, and pervasive self-effacement (“You play the Hobbyhorse, I’ll play the Fool”; “More fool me”), Selling England By the Pound is as close to a perfect album as any can get, and it is undoubtedly worth listening to and enjoying again and again.