Christopher Rush

Moving into the ’70s (Sort Of)

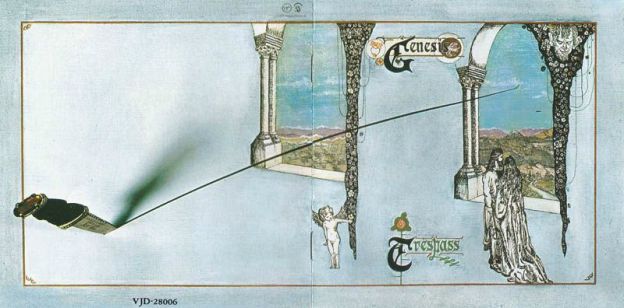

Genesis had parted ways with Jonathan King. John Silver had been replaced by John Mayhew on drums. The band was now signed with Charisma Records, a major source of progressive rock in the early 1970s. With Charisma came Paul Whitehead, the graphic artist who would create the covers of Trespass, Nursery Cryme, and Foxtrot (as well as several other covers for Charisma). Free from the constraints of Jonathan King, and having some studio recording and live performance experience under most of their belts, Genesis was poised to become one of the premiere prog-rock band of the ’70s. But first…

Trespassing Between Folk and Prog

Trespass has suffered slight disrepute and ignominy for years (though, perhaps even a bad reputation might be better than the near-total absence of a reputation that their clandestine debut album has), though the final song “The Knife” became the first real hit of the band, both critically and live on stage. Despite this, the album as a whole is the second part of their maturation process (their “teenage years,” if you will) — on the precipice of full-grown development. Some may argue that their third album, Nursery Cryme, is the culmination of their maturity, leading to the high-water greatness of Foxtrot, Selling England By the Pound, and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway before their next great self-reinvention after Peter Gabriel’s departure. To a degree that is true, and we will discuss Nursery Cryme more in our next issue, but it is an underappreciated album that bears more connection to the three great albums just mentioned than it does to the hybrid-like electric folk and mellotron-powered prog rock of Trespass.

Instrumentally, Anthony Phillips, Michael Rutherford, and Tony Banks have more diversity on this album: the acoustic twelve-string guitar is prevalent, as well as the dulcimer, nylon bass, and Banks’s mellotron (made most famous by the opening sound of Foxtrot). Without the synthesized strings and brass that mostly plagued From Genesis to Revelation (mainly because the band didn’t want them), the sound of the album is more genuine as a Genesis album. It has a folksy feel throughout, undeniably, but that isn’t necessarily a detrimental thing. Peter Gabriel’s vocal abilities shine through far more than they did on the limitations of their pop debut, reaching great emotional peaks during the album, especially in “Visions of Angels,” “Stagnation,” and “The Knife.” His flute work (and tambourine work) helps create the diverse woodsy, almost Tullian feel scattered throughout. Many critics consider the sound of the album as invoking the part-Romantic, part-Victorian idyll — though the end of “The Knife” is more of a police riot as the idyllic loss of innocence and natural purity comes to a dramatic conclusion.

The Paul Whitefield cover may not capture the essence of the album as overtly and succinctly as his covers for Nursery Cryme and Foxtrot do, but once you have listened to the album a few times (with the lyrics in front of you some of those times, though not necessarily the first time through) the relevance to the songs will make sense — it’s not a direct representation but a satisfying pastiche of many of the album’s major ideas. The dull blue/gray dominance of the cover art might account, in part, for the general dissatisfaction with the album as a whole, but the prevalence of the empty grayness has a great deal to do with the album’s general tenor: the vital, natural days of happiness are disappearing, only to be replaced by empty nothingness. The panoramic natural view from the window capture the idyllic aspects of the album, while the royal couple gazing upon it provide the narratorship for most of the songs here. The Cupid-like cherub could be one of the angels all around from “Visions of Angels,” and the floral curtains could be from any song. The mysterious face in the upper-right corner sometimes looks like a demon, sometimes a faun — perhaps you should figure it out yourself. The most obvious connection from the cover to the album content is the giant knife cutting a swath through the entire painting — though, of the several different bladed objects mentioned during the album, to which one it is referring (if not a combination of them) is the real question. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the cover is the knife itself, clearly a “real” knife cutting through the painting, adding an additional layer of reality to the complexity of Genesis’s transformation. Just as “The Knife” is about the end of life as we know it (at least the way we are used to it), the knife cuts through the final, forlorn gaze of the noble couple on the life they used to love (perhaps being blanketed by an angel and demon); superimposed on all of that Genesis itself is both cutting ties with its pop roots while also about to sever ties with the overt folk rock of Trespass in favor of all-out prog rock for the remainder of the Peter Gabriel era.

“Looking For Someone”

Genesis’s re-creation begins with an appropriate lyrical comment and attitude: “Looking for someone, I guess I’m doing that.” The band is definitely looking for a new beginning, certainly looking for an audience, and the lack of certainty in the narrator (“I guess”) fits the transitional nature of the album as a whole — better than From Genesis to Revelation but not yet the level of Nursery Cryme (definitely not Foxtrot or Selling England by the Pound). The narrator continues with “Trying to find a mem’ry in a dark room / Dirty man, you’re looking like a Buddha / I know you well — yeah.” The collage of unrelated images is confusing at best, but the “mem’ry” trying to be found for this album is an early glimpse of the antique scene depicted on the cover: the memory of days long ago, better days that have been destroyed by various factors — poor memory not the least of them. Doubtful it is that we are to associate the “I know you well” with the “Buddha,” as if the narrator has spent time searching out the mystical paths to Enlightenment and inner tranquility; one would suspect the narrator to be more self-assured were that the case — unless, of course, the narrator has spent time with Buddhism and is still confused. The uncertainty of the narrator continues as the need to “Keep on a straight line, I don’t believe I can” is followed by more difficult tasks ahead: “Trying to find a needle in a haystack / Chilly wind you’re piercing like a dagger / It hurts me so — yeah.” As mentioned above, the dagger is a pervasive image throughout the album, introduced here. The brief musical force of the previous line is dimmed subito for the great ironic line, “Nobody needs to discover me / I’m back again” — this is exactly what the audience must do! Genesis does indeed require the audience to discover them now that they are back again, now with an album more akin to their forthcoming mature sound and style. The melodic tendency to rapidly crescendo to dramatic hits is next demonstrated by the remainder of the chorus-like section: “You see the sunlight through the / Trees to keep you warm / In peaceful shades of green. / Yet in the darkness of my mind / Damascus wasn’t far behind.” The king and queen surveying the remnants of their territory on the cover of the album do behold a forested landscape that may well remind them of warmer, brighter days, roaming through forests free from care. If this album is an English idyll, perhaps the reference to Damascus places the time period of this opening song after the Crusades and Richard I’s defeat (of a sort) of Saladin at the close of the twelfth century, when the king and queen on the cover remember periods of both carefree days (“sunlight through the trees”) and days of war and loss — yet both of those periods are so long ago no one can remember them clearly today.

The time period jumps ahead. “Lost in a subway, I guess I’m losing time,” he says. “There’s a man looking at a magazine. / You’re such a fool, your mumbo-jumbo / Never tells me anything — yeah.” Not even periodicals and modern technology can restore the innocence and intelligence lost so long ago. The return of the chorus, now in its modern-day dress, brings more resolve on the narrator: no one needs to discover him because he is ready to be his own man. Genesis did not need the tutelage that led to From Genesis to Revelation, since they wanted to be their own band with their own style — perhaps that cry for independency continues through the rest of this version of the chorus: “You feel the ashes from the / Fire that kept you warm. / Its comfort disappears / But still the only friend I know / Would never tell me where to go.” All the direction given before has lead nowhere; it is time to be autonomous, to create one’s own style. The musical interlude that follows, the first real forceful musical outburst of Genesis’ album career, is the beginning of that autonomy (with rare tones from Peter Gabriel’s flute sprinkled throughout).

In Genesis’s attempt to find direction (“Looking for someone”), it has now found itself: “And now I’ve found myself a name” — the name of the band is the same, but the sound and direction are different (though still with the motifs and foreshadowed bits mentioned in the previous article), and the name “Genesis” is starting to become what it will mean during the rest of Gabriel’s direction. The rest of the lyrics of this song, “Come away, leave me / All that I have I will give. / Leave me, leave me / All that I am I will give” remind the audience of their initial invitation to join them in From Genesis to Revelation, but now that the band is breaking out on its own, it is willing to give of itself all it has, provided it is left alone to be itself. They are starting to trust their own musical and lyric instincts (still maturing though), and we are to do so as well.

“White Mountain”

“White Mountain” is as close to an E. J. Erichsen Tench fairy tale as rock music will ever get. The opening music of the piece is mildly reminiscent of medieval Christmas ballads, furthering the pervasive Victorian-idyll mood Trespass emits. From the opening verse (an inaccurate way to describe the narrative progression of Genesis’s material) we get the first reference to the title of the album: Fang, the traitorous wolf, has trespassed where only the leader of the wolves may go and learned of the secret crown and scepter of, perhaps, the king depicted on the cover of the album, placing the events of this song somewhere between the time periods covered in “Looking for Someone” (from the perspective that the songs on this album are connected). One-eye, the rightful ruler of the wolves, and his followers are out for retribution, and Fang is surrounded by a web and a sleeping fox: no matter how cunning he can be, it won’t be enough; he will soon be caught, trapped by his own importunate curiosity.

Fang soon encounters the steep path of the mountain, knowing that only descent will save him — but in this, too, he betrays his wolfish nature and clan rules: “A wolf never flees in the face of his foe,” and this is exactly what Fang does, cementing his guilt and forfeiting his life. One-eye and Fang face off in their climactic duel, but Fate has already decreed against Fang the usurper. One-eye is said to raise the scepter and use it against Fang, blurring the lines between animal and human — adding a lycanthropic aura to the characters and song. The next morning, the white mountain stained with Fang’s traitorous blood, One-eye buries the unlawfully uprooted crown and scepter of the gods and peace is restored in the wolf kingdom, the laurels of victory proclaiming One-eye’s rightful authority. The idyllic twelve-string strums and haunting whistling through the deserted blood-dimmed mountains send this unusual song into the ether.

“Visions of Angels”

The theme of lost innocence and lost youth returns here, straining against musically delightful tones. The narrator tries to look at the trees “but there’s not even one.” He runs to the smiling stream nearby “but the water’s dry.” He looks to his girl’s face and tries to take her hand but “she’s never there.” Why? We’re never told. “I just don’t understand / The trumpets sound my whole world crumbles down.” That’s pretty serious. After this realization of the complete absence of life-giving nature and love, the chorus proclaims “Visions of angels all around / Dance in the sky / Leaving me here / Forever goodbye.” Based on the propinquity of the declaration of the nearby dancing and utterly uninterested angelic realm to the declaration of the narrator’s world crumbling down, the cosmology of this world is getting increasingly desolate. The music accompanying the talk of angels is fitting for a heavenly realm, but the irony of the angels’ disinterest in the affairs of men is inescapable.

Desperation and despondency continues in verse two: “As the leaves will crumble so will fall my love / For the fragile beauty of our lives must fade / Though I once remember echoes of my youth / Now I sense no past, no love that ends in love.” The sentiment is clear enough. If the narrator is the king from the cover (which would make sense, but we are not here to force a thorough-going structure onto the album — even if the narrator of this song is unrelated to the cover or any other song on the album, the interpretation is similar enough), we are back in the decline of the Middle Ages. Not only are the warm, happy days gone, but also hope itself is fading quickly. The situation is becoming increasingly embittering to the narrator: “Take this dream the stars have filled with light / As the blossom glides like snowflakes from the trees / In vengeance to a god no-one can reach.” The impotent angelic realm is joined by an equally uninvolved deity. Happiness and hope are so far gone the king’s dreams are now just vitriolic attrition against the god that has allowed this destruction to occur. Musically, the song is part military cadence, part ballroom dance number — the confusion of sounds and styles is fitting for a song about conflicting emotions and reactions.

After another chorus reveling in the angelic realm’s disinterest in the affairs of men, the final verse sees the melancholy nostalgia of the narrator morphed into anger: “Ice is moving and world’s begun to freeze / See the sunlight stopped and deadened by the breeze / Minds are empty bodies move insensitive / Some believe that when they die they really live / I believe there never is an end / God gave up this world, its people long ago / Why she’s never there I still don’t understand.” Does the king think God is a woman? Perhaps — or that his thoughts have returned to his wife and her distance from him as well. His whole world has indeed crumbled down — and the angels keep dancing all around.

“Stagnation”

The preamble to this song returns us to the present age: “To Thomas S. Eiselberg, a very rich man, who was wise enough to spend all his fortunes in burying himself many miles beneath the ground. As the only surviving member of the human race, he inherited the whole world.” I’m pretty sure they made this guy up, but if not, he’s one of those eccentric rich British guys from a century or two ago; in other words, a rich British guy. The song itself is one of the more diverse and impressive on the album: it is probably getting tiresome to read comments about Genesis foreshadowing their future greatness, but this song, even more than the more popular “The Knife” at the close of the album, is a sign of the burgeoning diversity and musicality of the band.

The album thus far has been about stagnation: final glimpses of what is being lost and fading memories of what once was; yet, “Stagnation” is not about giving up and letting go. By the end of “Stagnation,” the king (again, assuming the narrator of this song is the king from the cover) is determined, like the narrator of Dylan Thomas’s most famous poem, not to go gentle into that good night. The song as a whole is Gabriel’s best lyrical work to date, unquestionably: “Here today the red sky tells his tale / But the only listening eyes are mine / There is peace amongst the hills / And the night will cover all my pride.” The synesthesia is delightful, coupled by the few moments of peace in the album; instead of another angry tirade against Fate, impotent supernatural beings, and Nature, we have the quiet acceptance of one’s downfall as so often brought about by hubris. “Blest are they who smile from bodies free / Seems to me like any other crowd / Who are waiting to be saved” ends the first verse-like section of this song. Is he referring to the stars smiling down, free? or the previous angels vindicated for their indifference? Perhaps — just as distant and uninvolved as people, waiting to be saved, too passive. And then comes the great turn. Musically the song has been fast, almost careering out of control. The realization of his connection with the natural world, and the fate of others, yields a pause in thought. The musical interlude is more Pink Floyd than Genesis, but only temporarily. When the hit comes again, powered by impressive sounds from Tony Banks, the king has a better self-understanding.

“Wait, there still is time for washing in the pool / Wash away the past. / Moon, my long-lost friend is smiling from above / Smiling at my tears. / Come we’ll walk the path to take us to my home / Keep outside the night. / The ice-cold knife has come to decorate the dead / Somehow.” The knife returns again, promising to destroy all that is known — but now the king will not idly give in. The queen whose fidelity has been questioned throughout may be back, though the king referring to it as “my home” might belie that — it matters little; what matters is the return of the resolution of the king to live and enjoy the day and keep the night of death at bay for as long as possible.

“And each will find a home / And there will still be time / For loving my friend / You are there / And will I wait for ever beside the silent mirror / And fish for bitter minnows amongst the reeds and slimy water.” This interlude, both emotionally and musically, is the real highlight of the album. It is a fine example of Genesis’s ability to becalm a situation and then build up to a powerful climax. “I, I … said I want to sit down. / I, I … said I want to sit down. / I want a drink — I want a drink / To take all the dust and dirt from my throat / I want a drink — I want a drink / To wash out the filth that is deep in my guts / I want a drink.” The climax of “Stagnation” rivals later Gabriel-era Genesis songs: Peter Gabriel’s vocal performance here is surpassed only by the unsurpassable finale of “Supper’s Ready” on Foxtrot (though, the greatness is comparatively short, and many other later songs as wholes are better than the whole of “Stagnation”). His flute work after the climax leads to a satisfying march-like resolution supplied by the ethereal chorus: “Then let us drink / Then let us smile / Then let us go.” The song winds down — though it certainly doesn’t stagnate — and dusk falls.

“Dusk”

“Dusk” is a good example of the band’s need to grow, especially Gabriel’s need to tighten up his lyrical creations. The song is simple enough, though hard to place in the dual chronologies of the previous songs. The Victorian idyll sound dominates with no break or contrary theme, which is not bad, since the song is so short it needs little variety. It is almost a call-and-response song, with Gabriel’s voice dominating the initial verses and the ethereal chorus replying with an impressively parallel pair of choruses (and a third chorus unlike the first two).

“See my hand is moving / Touching all that’s real / And once it stroked love’s body / Now it claws the past” is verselet one. The tone of Gabriel’s voice does not sound like the voice in previous songs, making the narrator of this song most likely a different persona from the album thus far. The thought of the lost past continues, as the hand that once touched the body of a loved one now can only claw at the past (a good verb, though the song as a whole reminds us clearly of Gabriel’s youth and relative inexperience at creating lyrics). The ethereal chorus responds with “The scent of a flower / The colors of the morning / Friends to believe in / Tears soon forgotten / See how the rain drives away another day.” The disjunction of the ideas is more reminiscent to us today of any typical contemporary “Christian” chorus of seemingly unrelated Bible words than the depth and brilliance of more mature Genesis lyrics. The musical interludes, though, help distract us away from the near-inanity of the lyrics, reminding us again of the maturing skill of Banks, Rutherford, and Gabriel (Phillips and Mayhew are maturing as well, but since they depart the band after this album, it almost doesn’t matter — Phillips has a very successful career later, but Mayhew sort of disappears into the mist).

Verse two: “If a leaf has fallen / Does the tree lie broken? / And if we draw some water / Does the well run dry?” The questions seem deep … but they aren’t, not really, especially since the connection to the ideas that begin the song is tenuous at best. The most impressive part of the song comes from the second chorus/response and its parallel to the first one, at least initially: “The sigh of a mother / The screaming of lovers / Like two angry tigers / They tear at each other. / See how for him lifetime’s fears disappear.” Are the sigh and scream the two angry tigers tearing at each other, or just the screaming of the lovers tearing at each other? I really don’t know, but I suspect neither does Peter Gabriel, so it’s okay. Another enjoyable yet brief musical interlude sets us up for the final vocals of this brief, ambivalent song.

“Once a Jesus suffered / Heaven could not see Him. / And now my ship is sinking / The captain stands alone.” We don’t need to get up in arms about Gabriel’s notion about Heaven unable to see Jesus — the brief references to a worse-than-deist god earlier in the album are far worse than this speculation; besides, it may be partially true that Heaven could not see Christ on the cross while He was bearing the sins of the world. The later couplet is more pertinent to the general direction of the album (since we know Jesus recovered far better than Gabriel could imagine — either of them, really). Instead of the kingdom sinking and the king standing alone as it has been thus far, now the narrator is a captain of a sinking ship, alone on the bridge. The chorus’s response is enigmatic but strangely fitting for this song: “A pawn on a chessboard / A false move by God will now destroy me / But wait, on the horizon / A new dawn seems to be rising / Never to recall this passerby born to die.” Despite the brief optimism, it is nothing like the strong renewed resolution in “Stagnation.” Here it is another aspect of Gabriel’s lyrical growing pains. A final twelve-string/piano chord-dominated finish leads us to the final (and one of Genesis’s most frenetic) song of this part-idyll, part-maturing transitional album.

“The Knife”

The original album jacket provides this dedication on this song: “For those that Trespass against us.” This is the only direct reference to the album’s title other than the lyrical reference to Fang’s trespass crime in “White Mountain,” but the “knife” reference has pervaded the album, leading to this modern metaphorical usage. Not since the ending of “Looking for Someone” have we been clearly in the contemporary time period on this album, but that changes with a stark reappearance of gun-shooting chaos by the close of this song. Moments ago, I mentioned that “The Knife” is one of Genesis’s most frenetic songs in its entire oeuvre, and that’s true — that’s not to say they never play fast-paced songs, they do; but the pounding nature of this song, mimicking a growing cacophonous riot between constabulary and a demagogue’s posse, is rare for this band. Even the pounding opening of “Watcher of the Skies” on Foxtrot (and sections of “Supper’s Ready” on the same album) does not reach the malevolent frenzy of “The Knife.” The previous “knife” references on the album have been about destroying and ending. Now, it is personified as a seemingly well-intentioned revolutionary who, essentially, is only using force to establish his own tyranny at the expense of others, bringing life as we know it to a more malicious close than the simple outright destruction of other daggers and knives. Additionally, it may be about law enforcement representatives who are likewise readily willing to use violence to solve problems and quell disturbances. Knives allow for little stagnation after all.

The danger of young radicals and their philosophies is delineated in the otherwise fine-sounding lyrics that spring forth with the rapid organ pounding of Tony Banks: “Tell me my life is about to begin / Tell me that I am a hero / Promise me all of your violent dreams / Light up your body with anger. / Now, in this ugly world / It is time to destroy all this evil. / Now, when I give the word / Get ready to fight for your freedom / Now — / Stand up and fight, for you know we are right / We must strike at the lies / That have spread like disease through our minds. / Soon we’ll have power, ever soldier will rest / And we’ll spread out our kindness / To all who our love now deserve.” Such is the rallying cry of most would-be tyrants and despots who, like Marius and Enjolras, think they are doing the right thing for the right reason. The problem with this line of “thinking” comes in Gabriel’s pointed couplet at the end of this tirade: “Some of you are going to die — / Martyrs of course to the freedom that I shall provide.” The motivation is clear: it is about power, not about justice or right — isn’t that often the way?

Any grip on morality is lost by the time verse two comes around: “I’ll give you the names of those you must kill / All must die with their children. / Carry their heads to the palace of old / Hang them high, let the blood flow. / Now, in this ugly world / Break all the chains around us / Now, the crusade has begun / Give us a land fit for heroes / Now —.” The “stand up and fight” chorus returns after this. It is clear the narrator does not truly want a land fit for heroes, since real heroes will in turn displace this power-motivated revolutionary, like Robespierre’s fate. The lyrics of this section were changed slightly during live performances, but those emendations are irrelevant here: the point of the song is the same on the album and live on stage.

Both of those verses come out in a rapid pace, and though the audience probably thinks the song is almost over based on the number of words Gabriel has just sung/chanted at them, we are barely two minutes into a nine-minute song. Suddenly the speed evaporates and the words disappear, and we are waiting for the mob of “freedom fighters” to attack the police barricade. Soon a quiet and menacing chant of “We are only wanting freedom” begins, supported by other chants the attentive listener will hear, followed by modern police/riot squad responses: shots are fired over their heads and the battle commences, slowly at first, then forcefully and rapidly. The pulsating tones during the “battle scene” help one realize why this song was so popular during early live concerts (though it sounds nothing like the “Battle of Epping Forest” forthcoming on Selling England By the Pound). Soon the rioters win, and we can only guess how many “martyrs of freedom” have suffered for this would-be patriot soon-to-be-dictator. Though we have come a long way from the idyll reverie of the medieval king from the cover, the pervasive knife of destruction was worked its way along the entire tapestry of the album.

“Tell Me My Life is About to Begin”

Though “The Knife” ends somewhat pessimistically, the album as a whole is a fine beginning to the real initialization of Genesis’s career. It is an optimistic album, with a sound unlike most albums of its time and certainly unlike most albums created today. Many more changes were about to occur in the life of the band: “The Knife” was soon released as a single, though the cover of it is anachronistic (an odd charge for the album just discussed, admittedly). The cover bears the five-member line-up of the “classic years” of Genesis: Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins, Mike Rutherford, Tony Banks, and Steve Hackett — even though Collins and Hackett did not play on “The Knife” or Trespass and only came on after its release to replace John Mayhew and Anthony Phillips, respectively. This line-up would create the seminal albums of Genesis’s Gabriel-era career: Nursery Cryme, Foxtrot, Selling England By the Pound, and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. Having gone through their lyrical and musical pubescence, Genesis was about to become what it wanted to be: the culmination of progressive rock in the 1970s, and one of the best rock bands of all time.