Christopher Rush

No Line (or Apostrophe) on the Horizons

Genius is rarely recognized immediately. Foxtrot reached only #12 on the charts in England and did not chart at all in America. These nonsensical historical anecdotes aside, in 1972, Genesis gave us one of the greatest musical experiences of all time: Foxtrot. The band is in full stride here, continuing its mature sounds and lyrical creativities from the success (if not commercial success) of Nursery Cryme. If there was indeed a sense of subdued relief at the completion of the diverse and inaugural classic-lineup album, the energy has been refreshed and renewed, as evidenced by the initial archetypal sounds of Tony Banks’s mellotron.

“Watcher of the Skies”

For any fan of good music, all one has to do is hit the play button (or drop the tone arm into the grooves) and emit the unmistakable sounds of Tony Banks’s Mellotron Mark II, and after but one second of the sound everyone will know instantly that this is “Watcher of the Skies.” It is that recognizable. The introduction is very good, despite the progression through discordant chords — even Tony Banks detractors have great difficulty in rebutting this powerful and energetic introduction. The gigantic sound sets the mood for the cosmic powers at play.

The lyric of the song is a strange supernatural tale about a galactic observer (doubtful it’s a supreme being, more likely a cousin or friend of Uatu) who discovers planet earth, apparently at the point of man’s last gasp, almost as if man is about to leave Earth behind — either because he is exterminating himself or because he is about to journey to the stars (but his self-destruction by his own devising is more likely). The title is taken from John Keats’s delightful “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (the poem that also gives us Keats’s great description of the world of art, literature, and beauty: the “realms of gold”): “Then I felt like some watcher of the skies / When a new planet swims into his ken.”

The story is ambiguous, as indicated in the uncertainty above: at times the words indicate life is going and possibly has been gone from Earth for a long time; other verses indicate that mankind is about to progress to another advanced phase: “Think not your journey done / For though your ship be sturdy, no / Mercy has the sea, / Will you survive on the ocean of being?” The optimism of man’s potential shifts again in the final verse, along with the potential downfall and isolation to the point of extinction of the Watcher himself: “Sadly now your thoughts turn to the stars / Where we have gone you know you never can go. / Watcher of the skies watcher of all / This is your fate alone, this fate is your own.”

With the immense power of the music of this opening track, finishing up the weight and vastness of the Stephen Vincent Benét-like lyrics, Genesis has satisfied both the audience that believed Nursery Cryme was the cusp of greatness and the audience that knew Nursery Cryme was the beginning of the band’s peak output. Gabriel’s lyrical skill has surpassed its tentative forays from the early years, building upon his initial attempts at ambiguity mixed with concrete emotional evocation, and achieving the longed-for narrative skill the band needed to complement its musical talents.

“Time Table”

In a way, “Time Table” continues the pattern Nursery Cryme set by alternating the fast-paced epic songs with the more melodic, almost quaint English life ballads. However, the pattern is not complete, since “Time Table” has a stronger, more emphatic chorus than “For Absent Friends” and “Harlequin.” Further, “Time Table” is more reminiscent of Trespass — the talk of kings and queens of old draws one back to that sophomore (not sophomoric in any way) effort. The precision of the language is better than those days, though, especially in the chorus: “Why, why can we never be sure ’til we die / Or have killed for an answer, / Why, why do we suffer each race to believe / That no race has been grander? / It seems because through time and space / Though names may change each face retains the mark it wore.” Not only is it refreshing that Gabriel is answering his own questions (finally), but also the melodic shifts of the “answer” lines are unlike any other motifs in the song, furthering the band’s connection between the music and the lyrics as integrated and integral aspects of their poetic/musical output.

The verses are reminiscent of Tu Fu’s “Jade Flower Palace” with a dash of Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” Without trying to imply that Peter Gabriel is a better poet than either of those world masters, “Time Table” is a better lyric than those poems (though I admit I have only read “Jade Flower Palace” in translation — perhaps the original surpasses Gabriel). The fullness of the title itself is more creative than the simple declaratives of the other two titles. Initially is the extreme Britishness of the time table itself, harbinger of trains, schedules (with a “shed” sound, not “sked,” of course), and punctuality rivaled only by the Germans. “Here is a song of the passage of time, how it has been chronicled and organized since the days of Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” says the title.

Four words into the song, though, the title takes on additional layers of significance: “A carved oak table, / Tells a tale….” The time table is, in fact, an actual table, a carved oak table. The layering is doubly rich: not only have we the table itself telling the tales by evoking memories “[o]f times when kings and queens sipped wine from goblets gold,” but the table is of carved oak, recalling to mind the aspect of knowing a tree’s age by cutting it down and counting its rings, telling a tale of its age and the weather incidents that affected its development and trunk life. The title of this song is rich indeed.

The Britishness of the song continues, as the carved oak table tells the tale of English kings and queens and their glory halcyon days of old, when “the brave would lead their ladies out the room / To arbors cool. / A time of valor, and legends born / A time when honor meant much more to a man than life / And the days knew only strife to tell right from wrong / Through lance and sword.” The subtlety of Gabriel’s lyric is impressive: what starts out as a nostalgic look backward to medieval jousting combats, feasts, and castles suddenly becomes a diatribe against uncivilized barbarity. It seemed like a civilized time of honor and nobility, but their definition of glory (evinced by Ivanhoe himself) was, fundamentally, “might makes right.” The chorus, quoted above, furthers the political overtones of the song. Beyond the medieval imagery, the song is a universal denunciation of all xenophobic military mindsets, British or otherwise. The winsome music accompanying the “answer” section of the chorus turns out to be an almost ironic response, as if the answer is so self-evident it can’t be answered with a straight face: human nature (barbaric, aggressive) never changes.

Verse two is even more reminiscent of “Jade Flower Palace”: “A dusty table / Musty smells / Tarnished silver lies discarded upon the floor / Only feeble light descends through a film of grey / That scars the panes.” The narrator cannot even recall the scenes with zestful authenticity anymore; the oak table, once a sign of strength and security, is just a collector of dust. The cool arbors are replaced by musty smells. The refulgent gold goblets and chargers are scarring, miasmic, filmy grey memories. “Gone the carving, and those who left their mark, / Gone the kings and queens now only the rats hold sway / And the weak must die according to nature’s law / As old as they.” Gabriel works in another great subtle line, as the carved oak table (first carved as an example of craftsmanship, now carved as a memory bank of those who sat and dined, lived and loved there) is shown against the scarring light — the notches of conquests are now the scars of memories and the scars of faded glory. The strong warriors and leaders fell away, succumbing to the passages of time and the unconquerable reign of nature. The lament-filled chorus returns and the Trespass-like sounds soon play the memories into oblivion. The fading dulcimer tones are quite appropriate for the final moods of the song.

“Get ’Em Out By Friday”

In the vein of “Harold the Barrel,” “Get ’Em Out By Friday” is a multiple-narrator story, but the song as a whole is more complex (which does not imply “better”) and more social awareness-oriented like Selling England By the Pound. Without looking at the words the first time one listens to the song, one might suppose the song is about shipping clerks, but it’s not, unfortunately. The song has three main characters: John Pebble of Styx Enterprises, Mark Hall of Styx Enterprises (“The Winkler”), and Mrs. Barrow (a tenant). Not too much time passes before we realize Styx Enterprises is not about the band (especially since the band had not yet reached mainstream popularity) but the Underworld. Pebble and The Winkler are clearly in league with Satan, but the song is not as darkly supernatural as that accusation implies.

John Pebble is a landowning entrepreneur in the most acquisitive and degrading senses on the word: “Get ’em out by Friday! / You don’t get paid ’til the last one’s well on his way. / Get ’em out by Friday! / It’s important that we keep to schedule, there must be no delay.” Before the first verse is over, Pebble makes his priorities clear: profit is the supreme good. The well-being of people, even employees, is irrelevant. The legality of Pebble’s threat that his employees won’t get paid until they finish evicting all the tenants is suspect, but who knows what wage systems were in place in 1970s England.

Mark “Winkler” Hall follows orders. “I represent a firm of gentlemen who recently purchased this / house and all the others in the road, / In the interest of humanity we’ve found a better place for you to go-go-go-go-go.” The Winkler puts the most dangerous spin on economy: the interest of humanity. The real interest, of course, is Styx Enterprise’s profit interest. Mrs. Barrow, poor tenant, provides the typical human response (phrased in a typical British way): “Oh, no, this I can’t believe, / Oh, Mary, they’re asking us to leave.” Since The Winkler is asking them to leave, it’s possible that Styx Enterprises has no legal recourse to evict the people after all, especially since his supreme value of profit does not allow basic human sentiment. If they had the right to evict them, they would do so immediately, especially without bribing them to move.

Back at Styx Enterprises, Mr. Pebble is upset and flustered: “Get ’em out by Friday! / I’ve told you before, ’s good many gone if we let them stay. / And if it isn’t easy, / You can squeeze a little grease and our troubles will soon run away.” Like a typical Barney Miller slum lord, Pebble is concerned about immediacy of his plans and is willing to resort to a slightly smaller profit margin (with distributed bribe money) if it forestalls widespread public awareness of their methodology.

Mrs. Barrow’s response to The Winkler is confusing. She desires to stay in her home so badly she offers to pay twice her current rent, but she allows him to convince her to take 400£s and move to a flat with central heating based on a photograph. She even admits they’re “going to find it hard” at that place. Now that Pebble has his way, acquisitiveness rules again: “Now we’ve got them! / I’ve always said that cash cash cash can do anything well. / Work can be rewarding / When a flash of intuition is a gift that helps you excel-sell-sell.” I’m not certain acquisitiveness is either a gift or a flash of intuition, but pecuniary-minded people think strangely about reality. The Winkler informs Mrs. Barrow that her rent for her new place has been raised, to which she responds, “Oh, no, this I can’t believe, / Oh, Mary, and we agreed to leave.”

A musical interlude indicates the passage of time, during which Styx Enterprises disappears, and Mr. Pebble has been knighted and now works for United Blacksprings International. I suspect Styx Enterprises has transformed into UBI, since “Blacksprings” is too like the river Styx to be anything but infernal. Now that the year is 2012 (in the song), a modern, futuristic name is needed to hide its diabolical business. In this futuristic world run by Satan’s Pebbles of the world, Genetic Control has declared that people will only be four feet tall, in order to fit more tenants in UBI’s tenements. The new representative of the common man, Joe Ordinary, who frequents the Local Pub-o-rama (definitely a British expression of the future), recognizes their shady and unscrupulous practices. As Gabriel sang in “Time Table,” the names have changed but the motivations and methods never do: “in the interest of humanity,” says Joe Ordinary, “they’ve been told they must go-go-go-go.” The interest is not of humanity, of course, but of the Blacksprings. Sir John de Pebble rouses The Winkler from some sort of dormancy (is he, after all, a spirit?): he has more work to do.

The end of the song is another layered ambiguity from the lyrically mature Peter Gabriel (whose name is incredibly ironic concerning this song). According to the liner notes, the last two lines are a memo from Satin Peter of Rock Developments Limited. Whether “Satin” is an accidental misspelling of “Saint” is unclear, though it could be an intentional Saint/Satan ambiguity (or Gabriel could be prefiguring Bryan Earwood’s typical spelling of “Satan”). I doubt Gabriel is positing Peter and Satan are the same, and as mentioned before, the song is not as overtly diabolical as this brief treatment may make it seem. Gabriel’s intelligence is shown by having Peter work for Rock Developments Limited, since, if it is really Saint Peter, Gabriel’s knowledge that he is the rock is impressive, even if he is somewhat derogatorily saying the developments of the rock (perhaps the church herself) are a “limited” enterprise, especially in contrast to the dominance of United Blacksprings International. The memo itself is again Blakean: “With land in your hand you’ll be happy on earth / Then invest in the Church for your heaven.” You can figure that one out for yourself.

“Can-Utility and the Coastliners”

Genesis’s range of source material has clearly transcended its scriptural From Genesis to Revelation beginnings. Trespass gave us, among others, the beast fable of Fang the wolf. Nursery Cryme showed their penchant for classical myth and Victorian fantasy. Here, on Foxtrot, Genesis extends their mythical range to the Viking King Canut (Cnut the Great) of Denmark, Norway, England, and parts of Sweden who ruled shortly before the Norman Invasion destroyed most of pre-1066 history. Cnut’s invasion of England was complete by 1016. By 1027, Cnut ruled the rest of those northern Norse men territories. Within a few years of his death in 1035, Edward the Confessor reigned, setting the stage for William the Conqueror thereafter. The apocryphal story has variations, of course. Supposedly King Cnut once placed his throne on the shore, tired of his sycophantic court, and commanded the waves to part and not wash upon his throne or his robes to demonstrate his true power (and mock his courtiers who believed the waves would heed him). Of course the waves did not honor his request and lapped around him. Some accounts, such as Henry of Huntingdon’s, declare Cnut then placed his crown on a crucifix and gave the glory to the God of the Bible as the deity whom the natural world obeys. Gabriel’s version here does not have that sort of climax, but it does relate a similar story as a whole.

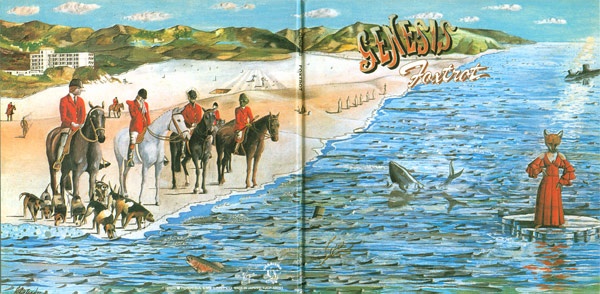

Gabriel personifies the natural setting, and the musical accompaniment at the beginning is as mellifluous as anything Genesis ever did, opening with one of the most evocative opening lines in their canon: “The scattered pages of a book by the sea, / Held by the sand washed by the waves.” No more mention is given of what this book was, though it may be fair to assume it is a book about King Cnut. “A shadow forms cast by a cloud, / Skimming by as eyes of the past, but the rising tide / Absorbs them effortlessly claiming.” The clouds as “eyes of the past” is a wonderful image, one of Gabriel’s best metaphors. As the verse continues, the shifting vocalizations and musicality increase as the tide and Cnut’s disappointment swell, leading into one of the most dynamic musical interludes not just of the album but in Gabriel’s entire tenure. Referring to Cnut as “Can-Utility” is impressively ironic again, since the entire story is about what Cnut could not do, though he was desperate for useful followers and worshippers, not mindless flatterers. The story follows the climax of Cnut’s experiment, as Hackett and Rutherford’s contributions mimic the waves and Cnut’s emotions. From reaction to worshipful declarations, the diversity in this song is most impressive. Instead of the Christian conclusion though (as can be supposed), Gabriel ends with a mysterious tag: “See a little man with his face turning red / Though his story’s often told you can tell he’s dead.” Much like “Time Table,” “Can-Utility and the Coastliners” (the Coastliners are most likely the unheeded flatterers who resemble fox hunters/hounds on the cover) reminds us of the passage of time during which the power and reigns of even the mightiest and proudest rulers will eventually conquer mortal rulers, no matter how often their stories are told (or re-imagined, as Genesis does here).

“Horizons”

Little needs be said about possibly the most beautiful song of Genesis’s career. Though the re-mastered cd release calls “Horizon’s,” the title has no apostrophe. Steve Hackett’s masterful work is a marvelous prelude to the epic “Supper’s Ready,” making the B-side of Foxtrot probably the best B-side in the history of music recording. It has been noted that Hackett begins with the central theme from Bach’s cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, but he soon progresses to his own baroque-influenced song. Like all the great soft Genesis numbers, one is almost left with the impression that it is too short, that there should be more song, but that, of course, misses the point entirely. It is a precisely-structured musical expression of the soul in a beautiful world — any more would be over-indulgence to the point of aural gluttony. We must re-train ourselves to appreciate and enjoy what is there and ask for no more.

“Supper’s Ready”

Oh, boy. Time for the great supernatural epic, one of the top-tier songs that defines Genesis’s career (by those aware of the Gabriel era, that is). Various accounts credit very bizarre sources for the inspiration of this mighty work (many of which do not have the same tone and direction that the song itself has), and the reader can seek those out at his leisure. Gabriel’s intro of the song in concert gives it a different context as well. At the outset of this series I indicated we were going to focus solely (as much as possible) on the lyrics and music of the songs themselves — admittedly, though, we have used some liner note stories and other historical references to explain some of the allusions where appropriate, and we will need to do a bit more of that here. As for The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway next issue…well, we’ll cross that bear when we get to it. Though we won’t utilize all the interviews and dvd bonus material available for simplicity’s sake, we will use quotations from the 1972-73 concert tour handout that explains (in typical covert Gabriel fashion) the story. The nearly twenty-three-minute musical epic is divided into seven sections, in a variation of the sonata form.

I. Lover’s Leap

The opening scene of the magnum opus is a calm, quiet evening in a British home of two typical British young lovers (since the episodes that influenced the writing of this song were from Gabriel’s wife, we shall call the main characters a married couple, one woman and one man). The simple melody and restrained accompaniment hearken back to the folk days of Trespass. The couple seems to be newly reunited (“I’ve been so far from here, / Far from your warm arms. / It’s good to feel you again, / It’s been a long, long time. Hasn’t it?”), but it could also (or instead) be a metaphorical separation that is being bridged. The song opens with the male narrator turning off the television and looking into his wife’s eyes, perhaps for the first time in quite a while, thus necessitating the repeated encouraging line, “Hey my baby, don’t you know our love is true.” Outside this familial scene the supernatural is coming to life: “Out in the garden, the moon seems very bright, / Six saintly shrouded men move across the lawn slowly. / The seventh walks in front with a cross held high in hand.” Additionally, the wife is also going through supernatural transitions: “I swear I saw your face change, it didn’t seem quite right.” The mystical work outside completes the transformation of the couple inside. The guide summarizes this quiet scene of transformation nicely: “In which two lovers are lost in each other’s eyes, and found again transformed in the bodies of another male and female.”

II. The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man

“The lovers come across a town dominated by two characters; one a benevolent farmer and the other the head of a highly disciplined scientific religion. The latter likes to be known as ‘The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man’ and claims to contain a new secret ingredient capable of fighting fire. This is a falsehood, an untruth, a whopper and a taradiddle, or to put it in clearer terms, a lie,” says the guide. The melodic line of this section is recalled at the climax of the song in part seven, though the lyrics there are much more Biblical and life-affirming than the lyrics are here. The pacing and melody of the sounds in this section, though, are great. The challenge of this section is to discern whether Gabriel is satirizing (a gentle word for it) Jesus and Christianity (since he wore a crown of thorns during this portion of the song for some live performances); though Gabriel is not an overt Christian, I posit that he is not denigrating Christianity itself but the materialistic, “scientific” versions of it (such as televangelists and others of that ilk), primarily because of the biological science references. I hope I am not being credulous.

I don’t know if anything should be made of another farmer reference, though it is interesting that Genesis often speaks of farmers (“Seven Stones” from Nursery Cryme, “The Chamber of 32 Doors” from The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, among others). The farmer doesn’t seem to have much to do in this section of the song, though; after the brief mention of his skill and concern for his task caring for the natural world (in a Chaucer-like description), the focus shifts entirely to the GESM. I have no knowledge if Gabriel has read Fahrenheit 451, but it is clever that his fireman, the GESM, “looks after the fire” and doesn’t put out fires. The guide, quoted above, intimates the secret ingredient to fight fire is some sort of salvation, if the fire is the eternal fires of damnation from the Lake of Fire. This might contradict my earlier position that the GESM is not an attack on Jesus, but I don’t think it does. We know that Jesus does not provide falsehoods, untruths, whoppers, and lies about the afterlife — even if the GESM is an attack on the Bible, Gabriel would be wrong, and there would be no need to be concerned, provided we then explained this misconception rationally and thoroughly. If the GESM is just a type of false gospel promoter, Gabriel is thoroughly correct that the technological, scientific “secret” is “a lie.”

The quiet chorus after the final lyrical and musical climax of this section is difficult to understand: “We will rock you, rock you little snake, / We will keep you snug and warm.” The quietude of the conclusion transforms into a flute recapitulation of the “Lover’s Leap” melody. This in turn prepares the way for the third section of the work.

III. Ikhnaton and Itsacon (Its-a-con) and Their Band of Merry Men

“Who the lovers see clad in greys and purples, awaiting to be summoned out of the ground. At the GESM’s command they put forth from the bowels of the earth, to attack all those without an up-to-date ‘Eternal Life License,’ which were obtainable at the head office of the GESM’s religion,” according to the guide. Ikhnaton is none other than Akhenaten, the Egyptian pharaoh and husband of Nefertiti, whose “Great Hymn to the Aten” we read in 10th grade. The GESM conjures him and Its-a-con (furthering the song’s antipathy toward false religion and pseudo-scientific-intellectualism) and a mighty battle rages, as evidenced by the faster pace, louder percussion, and interaction and interplay of Tony Banks’s organ and Steve Hackett’s guitar. The arpeggiated musical break is one of the musical highlights of the entire album (and Genesis canon).

The verses of this section further the song’s satiric approach to such a diversity of subject matter, this time war. “Wearing feelings on our faces while our faces took a rest, / We walked across the fields to see the children of the West, / We saw a host of dark skinned warriors standing still below the ground, / Waiting for battle.” I’ll admit I don’t know who the “children of the West” are, nor do I fully comprehend what “wearing feelings on our faces while our faces took a rest” means, though I suspect it also connects to the attacks on hypocrisy throughout the number. Reminiscent of most battle songs from Genesis (“The Knife,” especially), Gabriel points out the paradox of war: “Killing foe for peace… / Today’s a day to celebrate, the foe have met their fate.” Like Homer, though more acerbic, Gabriel reminds us that “war, no matter how much we may enjoy it, is no strawberry festival.” The admixture of war satire with religion satire (“And even though I’m feeling good, / Something tells me, I’d better activate my prayer capsule”) makes the mostly music-driven section lyrically full. Once the battle is over, the momentum is rapidly lost, and the section virtually slams to a halt, despite the final line, “The order for rejoicing and dancing has come from our warlord.” (I’m pretty sure the live performances change it to “from Avalon,” but I could be wrong.) The rejoicing and dancing do not appear.

IV. How Dare I Be so Beautiful?

The battle is over and only chaos is left, chaos and Narcissus. “We climb up the mountain of human flesh, / To a plateau of green grass, and green trees full of life.” The transformed couple climbs a mountain of war-struck corpses to find Narcissus admiring his beauty in a pool in a forest sitting by the pool. Suddenly “He’s been stamped ‘Human Bacon’ by some butchery tool. / (He is you) / Social Security took care of this lad.” This brief interlude of a number hearkens back to the ambiguous lyrics of From Genesis to Revelation, which is ironic since the phrase “How dare I be so beautiful” was a favorite expression of the band’s manager at the time, Jonathan King. The connection of the “Human Bacon” stamp on Narcissus is most likely a reference to the battle carnage over which the couple has just ascended, since the “he is you” line furthers the representational nature of the previous section. It is rather nice that the government took care of its fallen soldiers through social security, though the sparse musical accompaniment of this section belies the sincerity of the words. It is a remarkably quiet section, but it is appropriate as the aftermath of such a battle. Similarly appropriate with the music is the couple’s quite reverent non-participation (only as observers) of the transformation of Narcissus into a flower, according to Ovid’s version of the myth. Like Narcissus (especially in variations on the myth), the couple are pulled down into the pool and the inane world of Willow Farm, resulting in a drastic shift from the direction of the song thus far.

V. Willow Farm

“Willow Farm” was a separate song worked in to “Supper’s Ready,” helping to distinguish it from other lengthy, unified narratives such as “Stagnation,” according to Tony Banks. This portion of the number gave us one of Gabriel’s most iconic moments during live performances: the flower mask. Lyrically, the song is diverse and often called Python-esque for its verbal wordplay (though it may be more Sellers-esque, if not Goon Show/Beyond the Fringe-esque). The couple has by now climbed out of the pool into a different existence, an unusual world that makes Wonderland seem like the Reform Club.

The opening section has the feel of being welcomed by Kaa the python into his lair — Gabriel’s voice has all the unctuous charm of impending doom for the listener. It is from this section we get a rare reference to a fox (“Like the fox on the rocks”), though the fox is not trotting, nor is it wearing a red dress like the fox on the Paul Whitehead cover of the album (Gabriel would sometimes wear a fox head and red dress during some Foxtrot song performances in concert). Perhaps the narrator is a Reynard the Fox character, since the fox reappears again in the next section of the song. The verbal rigmarole includes political commentary (“There’s Winston Churchill dressed in drag, / He used to be a British flag, plastic bag, what a drag”) and fable references (“The frog was a prince, the prince was a brick, the brick was an egg, and the egg was a bird / Hadn’t you heard?”). Gabriel even includes a sly self-reference to “the musical box.” Suddenly, a whistle blows, diverse sound effects occur, and the garden/woodland scene transforms into a typical British daily life tableau reminiscent of “Harold the Barrel.” The verbal flummery continues (“Mum to mud to mad to dad / Dad diddley office, Dad diddley office, / You’re all full of ball / Dad to dam to dum to mum / Mum diddley washing, Mum diddley washing / You’re all full of ball”), based more in the sounds of the words than in their denotative sense (perhaps precursoring A Bit of Fry and Laurie — the British love their intelligent, verbal humor, and their non-intelligible verbal humor, that’s for sure). Gabriel’s original narrative voice (mixing Grima Wormtongue with Uriah Heep) returns for the final few lines, and the menace grows until, just like the sudden climax before, the whistle blows again and the scene transforms: “You’ve been here all the time, / Like it or not, like what you got, / You’re under the soil, / Yes deep in the soil. / So we’ll end with a whistle and end with a bang / And all of us back in our places.”

VI. Apocalypse in 9/8 (Co-starring the Delicious Talents of Gabble Ratchet)

Unlike the peaceful follow-up to the abrupt end of “Ikhnaton and Itsacon,” the musical interlude between sections five and six does not fit with any previously-heard musical motifs, and its ominous timbre is not encouraging. Instead of “Gabble Ratchet,” the guide indicates the co-stars are wild geese, a version of the “hounds of Hell.” The ominous interlude quickly transmogrifies into a full diabolical performance as the rhythm section beats out a disjointing 9/8 rhythm. Gabriel dons a geometrical headdress for a Magog costume, and the apocalypse is upon us.

“At one whistle the lovers become seeds in the soil, where they recognize other seeds to be people from the world in which they had originated. While they wait for Spring, they are returned to their old world to see Apocalypse of St. John in full progress. The seven trumpeteers cause a sensation, the fox keeps throwing sixes, and Pythagoras (a Greek extra) is deliriously happy as he manages to put exactly the right amount of milk and honey on his corn flakes,” says the guide, which actually makes matters worse in its obfuscatory George S. Kauffman-era Marx Brothers style. We have traveled from seven shrouded saintly men from the garden to seven trumpeteers “blowing sweet rock and roll.” The apocalyptic language is a mixture of Revelation, folktale, myth, and William Blake, both here and in the final section. The musical variations during this section are more grinding and fretful than enjoyable, which is appropriate after a fashion for an apocalyptic climax (Tony Banks has commented that his organ solo was a parody of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer). Couched within the diabolical imagery is the essential warning of the song: “You can tell he’s (the Dragon, Satan) doing well, by the look in human eyes. / You better not compromise. / It won’t be easy.” The relevancy of Gabriel’s warning is even more relevant in the soul-siphoning digital age than it was during the uncertainties of the 1970s.

As Pythagoras writes out the lyrics to a new tune in blood (it’s doubtful Gabriel is equating geometric equations with the apocalypse, but he could be), the diabolical rhythms draw to a close, and we (and the couple) are saved from a disastrous fate as the opening melody from “Lover’s Leap” returns. As Dante’s successful navigation through the Underworld resulted in his restoration to Love and Truth, so, too, does our heroic couple’s journey restore their love. In a declaration reminiscent of Donne’s classic “Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” the journey has only strengthened their union: “And it’s hey babe, with your guardian eyes so blue, / Hey my baby, don’t you know our love is true, / I’ve been so far from here, / Far from your loving arms, / Now I’m back again, and babe it’s going to work out fine.”

VII. As Sure as Eggs is Eggs (Aching Men’s Feet)

The “Lover’s Leap” motif transforms directly into “The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man” motif, but the lyrics are much more uplifting than before. Though there are some elements of William Blake in there, the feeling the song evokes is pure Biblical catharsis. This is as great an ending to an epic as any out there in any medium. “Above all else, an egg is an egg,” says the guide. In pure British simplicity, the self-evidence of the conclusion both discards the symbolic language of the entire song and allows us to believe exactly what the words are saying, at face value. In simple logic, the tautology of the section title reminds us “as sure as eggs is eggs,” good will conquer evil, God will conquer Magog and the Dragon, and light will conquer darkness. (The “aching men’s feet” line is probably just another admission that the journey is done, the album is over, and the band is tired out again.) This is a great song, with an ending that puts to shame most (if not all) contemporary “Christian” music that gives us a pale, shoddy version of the glories of the life to come. As Phil Collins presses his climactic snare roll, Gabriel sheds his Magog costume for an angelic white costume declaring the victory of goodness over evil. “Jerusalem,” says the guide, “= place of peace.” What else is needed? Now we know what the title of the song means: the armies of the Dragon are defeated, and the angel (in Revelation 19:17) invites the birds to feast on the flesh of the wicked. Supper’s ready not just because the lovers are reunited, and not just because He has prepared the victory feast of His enemies, but more importantly because the Messiah (the Mighty One) has returned to prepare His marriage feast with His Bride, the Church.

Gabriel’s voice is as epic as it gets here. “Can’t you feel our souls ignite / Shedding ever changing colors, in the darkness of the fading night, / Like the river joins the ocean, as the germ in the seed grows / We have finally been freed to get back home. / There’s an angel standing in the sun, and he’s crying with a loud voice, / ‘This is the supper of the mighty one,’ / Lord of Lords, / King of Kings, / Has returned to lead His children home, / To take them to the new Jerusalem.” Now that’s a song.

“Now I’m Back Again, and Babe It’s Going to Work Out Fine”

By this point, the greatness of Genesis, especially in the Peter Gabriel era, should be evident to all. They were diverse and talented lyrically and musically. They told stories of apocalyptic battles and ballads of couples enjoying life and love. Their melodies and harmonies, vocally and instrumentally, can still surpass just about anything today. Their reputation commercially and in concert after the release of Foxtrot was no longer a well-kept secret. Foxtrot was their first album to break the top 20 in England, and most of these songs became staples of their concerts for years to come. Foxtrot is a great album from the first mighty chords of Tony Banks’s mellotron of “Watcher of the Skies” to Peter Gabriel’s worshipful exultations at the cathartic conclusion of “Supper’s Ready.” Listening to Foxtrot is a great experience that should be enjoyed again and again. Even for those who doubt the greatness of Nursery Cryme, Foxtrot is an uncontestable work of genius, cementing the greatness of Genesis.