Christopher Rush

The narrative structure of “Dear Peggy,” the tenth episode of M*A*S*H’s remarkable and crucial transitioning fourth season, is a complicated series of flashbacks and imbricated scenes held together by one of the series’ most enjoyable and popular narrative devices: the epistolary frame story. After the pilot episode’s extended opening minute and main titles, the series itself begins with Dr. Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce narrating over the action as if he is writing a letter to his father. Many other episodes in the early seasons are initially narrated as if they are letters, but it is not until the first season episode “Dear Dad” (the first of the series’ Christmas-themed episodes) that the epistolary frame story technique is used as the guiding and thorough narrative structure for the entire episode. The great advantage of such structured episodes is that the device allows for character-driven episodes without the need for a consistent, unified plot. The letter-writing episodes are usually “day in the life” episodes, in which the audience is shown diverse, brief character sketches of the 4077 gang involved in their own daily lives and experiences – and that is fundamentally what M*A*S*H (as with most successful television shows) is about: characters we come to know and love. We don’t care so much about what they do; we just want to spend some time with them, hanging out and enjoying ourselves, and that is what the epistolary frame stories and similarly-structured “mail call” episodes (in which we see various characters responding to mail they receive) of the series provide.

Most of these letter-writing episodes follow a non-linear re-telling of recent events or character moments, primarily through flashbacks. The discrete nature of the character moments affords a timeless quality (very useful in an eleven-season show about a three-year police action): because there is no cause-and-effect aspect to what each character is up to, when these character moments takes place is irrelevant. They are all, more or less, simultaneous occurrences (later honed by the “mail call” themed episodes). However, in season four’s “Dear Peggy,” the events that recent arrival Dr. B.J. Hunnicut describes are more interconnected and overlapping than most of the other letter-writing episodes, and thus the chronological order of events B.J. describes (and when he is actually writing about them, especially) becomes a necessary component to the storytelling itself.

Season four was, as mentioned above, a crucial season for the series. At the end of season three, Dr. Henry Blake was reportedly killed while flying back home after being discharged in one of television’s most shocking moments ever (the sound of the dropped surgical instrument, an accident, is one of television’s most memorable sound effects). When the fourth season begins, the audience, along with the series’ main character Hawkeye, soon learns that another mainstay of the show, Dr. “Trapper” John F.X. McIntyre has also been discharged and has gone home. Within fifteen minutes of programming, the series lost over 30% of its original cast. This new season, with two new characters replacing seemingly un-replaceable characters, would have to be an impressive mixture of new and old elements to keep the growing M*A*S*H phenomena alive. Fortunately, the creative behind-the-scenes team intentionally replaced the characters with opposing personalities, forever changing the make-up of the 4077 as we knew it – and it worked completely. Henry was replaced by Col. Sherman T. Potter, regular army and experienced leader. Trapper John was replaced by fun-loving yet family-oriented Dr. B.J. Hunnicut, fresh out of residency and ready to out-joke anyone in the camp. The new character types, as well as more serious plotlines and unique narrative techniques (such as Hawkeye’s solo episode “Hawkeye,” the classic newsreel footage interspersed “Deluge,” and the interview-driven season finale “The Interview”) propelled the series through many seasons and more cast changes.

It is easy for us today, over thirty years later, with the benefit of DVDs to take the direction of the series and, particularly for our purposes here, season four for granted. For the original audience, creative crew, and cast, however, they did not have such hindsight-laden advantages. “Dear Peggy” is the middle of three epistolary-framed episodes of the season (“Dear Mildred,” “Dear Peggy,” and “Dear Ma”), and, as noted above, is the most ambiguously ordered episode as far as the discrete plot elements are concerned. Coming half-way through the unusual season, the audience and all involved needed an episode to get to know B.J. Hunnicut better. Let us attempt to unravel the order of events both within the frame stories and B.J.’s letter-writing frame itself.

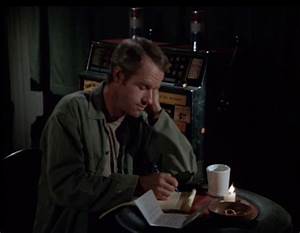

Scene 1 (S1) opens with the sounds of Father Mulcahy playing the piano, a rather jaunty tune; when we see him, he is clearly enjoying what he is doing. This may not seem like much at the time, but it could actually be crucial in determining the narrative order. Similarly, Klinger seems relaxed but tired, as evidenced by his attitude and sound of his voice when responding to Hawkeye’s initial jibe. Hawkeye is also tired and quite bored, not lugubriously so, but more so than usual. When B.J. first writes on screen, he quickly rubs his eyes, blinks, and stops writing, indicating how tired he is as well. After his tour around the room, Hawkeye approaches B.J. with an accusative “Writing home again? That’s your third letter this week.” B.J. does not correct him, indicating that during S1 B.J. is writing his third letter of the week – though “this week” seems more generalized, not directly per the calendar, since S1 is most likely a late Monday night. Hawk seems opposed both to B.J.’s letters and his stated reason for writing them (they are “the only way [he] can keep his sanity,” says B.J.), offering his own sanity as a substitute since he isn’t using it (“God knows” this, says Hawk, though Mulcahy calls him a “crazy agnostic” later in the episode).

S1 then focuses on B.J. again once Hawkeye makes his mildly theatrical departure, a somewhat symbolic representation of the entire season in microcosm. Believing Hawkeye’s accusation and B.J.’s lack of a correction, he is, indeed, writing his third letter of the week. However, the only written contribution to letter three (L3) he makes is his first line: “You can really go out of your mind here, Peg. There’s just nothing to do when you’re not working.” After he pens these sentences, he momentarily gives in to his tiredness. He stops writing, rubs his eyes and face, blinks, and stares off more or less at Radar and Nurse Kellye dancing. The rest of his thoughts are actually him remembering what he wrote in a previous letter, most likely the first of the week (L1). He is so tired he has to recall what he has already written so he does not repeat himself to his wife. In doing so, the audience learns snippets of his previous two letters. He recalls his reading of Justice Holmes, which leads him to think of Frank Burns, which then leads him to recall the first operation on Private Davis. His wording is crucial (as it is during the entire episode): “this morning,” says B.J., was the operation. It could not have been the morning of S1, clearly, and B.J. would not write that no matter how tired he is, so he can’t be internally writing L3 with these lines – he must be remembering a prior letter. The morning of the first Davis operation has to be at least 2 days before S1, as we shall see.

Scene 2 (S2) is the referenced morning of the first Davis operation. Hawkeye is operating one table over and seems tired already, but in a different way than in S1. B.J. is not noticeably tired, though undoubtedly his adrenaline kicks in as soon as he starts working on Davis as aggressively as he does. Frank gives up on Davis at the first loss of his pulse, though B.J. is unwilling to and saves him, using closed-chest massage he saw recently back in the States. Though B.J.’s voiceover disappears early in the scene, we must believe we are seeing what he writes about in L1, though he recalls it chronologically during the writing of L3.

Scene 3 (S3) begins with B.J.’s letter-writing voiceover telling Peg (and us) it is now “five in the morning.” He is sitting by Davis’s bedside, not on duty though in his coat, not able to sleep over the condition of Davis. Thus, S3 is a different day from S2 and S1, occurring between S2 and S1. During the rest of the day of which S2 was the morning, Klinger and Mulcahy learned about Davis, how tricky and unusual the operation was, and how little Davis has responded to both Frank’s half-hearted surgery and B.J.’s vociferous resuscitation. No doubt part of B.J.’s inability to sleep mixed with his tiredness is the loss of adrenaline working its way out of his system between S2 and S3. Because it is five in the morning, we may be able to assume the letter he is holding and writing is L1, since not enough time has passed between the remembered lines about Frank Burns and the Davis operation for B.J. to have finished a letter and begun a new letter with enough content for the “now” he writes (“It’s five in the morning now, Peg,” says B.J.) to make sense. The “now” clearly indicates a connection to the lines about the operation, making this still L1, though the first time we have actually seen it. B.J.’s ability to sit by Davis’s bedside helps prove his forthcoming statement “there’s just nothing to do when you’re not working,” though it is has already been spoken in the episode. Hawkeye wrote a similar idea to his father in an earlier episode, declaring their “greatest enemy is boredom.” When B.J. says he “was” worried about Davis in the past tense, he is only talking about his emotional state that motivated him to go to his bedside, not a temporal connection between the time he did it and time he wrote it to Peg.

Klinger’s dialogue helps place the position of S3. If, as is sometimes thought, S3 occurs after S1, and the letter B.J. is writing in S3 is a continuation of the letter he is writing in S1, how could Klinger have had time to not only win an egg in a poker game “last night” (considering how late and tired everyone is in S1)? Perhaps he could have had time for the dream of going home with Major Houlihan, but since Klinger also seems to be volunteering this early in the morning (considering he says he is about to go eat his egg for breakfast) and is rather cheerful and active, it is highly doubtful he is so filled with vigor and can remember a dream he had in so little time between S1 and S3. Klinger may be on duty, though, and just telling Mulcahy and B.J. what he is planning on doing later, considering how much time passes between S3 and S4.

Mulcahy also helps place the position of S3. In S1, he seems rather care-free. Knowing what we do about Mulcahy taking his character from multiple seasons, he is a bit of a worrier – he’s no Piglet, and he’s a fine priest to be sure (his doctrinal purity needs exploring another time, though), but it seems quite unlikely that if Mulcahy knew he was about to be visited and observed the next day by Colonel Maurice Hollister, Divisional Chaplain, he would not be up late, smiling and playing a merry tune, enjoying some harmless banter with Hawkeye. Also, since S1 seems to be a Monday or Tuesday, B.J.’s line in S3 about not needing Mulcahy “’til Sunday” would make more sense if it were closer to an upcoming Sunday, and we are positing S3 as early Saturday morning. (Of course, this is rather tenuous, considering Sundays occur with great regularity, even in Korea.) B.J. might have said “not until tomorrow,” if Sunday was the next day, but since it is only five in the morning and B.J. hasn’t gotten much sleep, his seeming stock response is acceptable (his rather knee-jerk offering to prescribe some drugs for Mulcahy’s nerves may be due to his tiredness, but it is somewhat worrisome, though fortunately never repeated). Some might argue the reason Mulcahy is also awake at five in the morning is because he is already nervous about Hollister’s impending visit (“this afternoon” he says) – this is rather likely, but it is doubtful still that he would be playing the piano and smiling only a few hours earlier then suddenly get nervous when Saturday begins. Thus, S3 takes place before S1, making the letter B.J. is holding in S3 different from the letter he barely works on in S1, thanks to Hawkeye’s reaction.

S4 clearly takes place later the morning of S3. Hawkeye enters the Swamp (B.O.Q. 6, though two-thirds of the residents in that tent are married), mildly disgusted with the noise and crowd that had gathered to see Klinger eat his fresh egg. The PA announcement then heralds a forthcoming cockroach time trials final at 1330 hours, thus S4 occurs between 0500 and 1330 hours – granted, eight hours is a fairly broad span of time in which to locate a brief scene, but other indicators might help specify its position. In response to Hawkeye’s announcement of Klinger’s crowd-observed egg eating, B.J. says he “just wrote that to Peg” in L1, assuming he is still working on L1, since it has only been a couple of hours from his earlier contributions to that letter. Since he is already in the Swamp, having opened Peg’s package, he seems fairly entrenched in his work, so B.J. probably wrote the content of S3, that Klinger told him he won the egg, not that he ate it. Hawk’s general tiredness continues as he takes a nap shortly after being introduced to the contents of Peg’s first overseas package. B.J. then relates to Peg that Hawkeye had read in Life magazine “that morning” about the world record for people stuffed in an automobile. Thus, Hawk’s reading took place between S3 and S4, and when B.J. says Hawkeye “thought” (past tense) they could beat the record, he is only referring to Hawk’s initial reaction of reading the article, not referring to their actual fulfillment of that, since the jeep-stuffing scene could not have yet happened when B.J. writes to Peg here in S4. Since Hawkeye had the idea “that morning,” S4 clearly is a different day from S1 and S2. It is logical to assume Hawkeye came directly from the crowd that gathered to see Klinger eat his fresh egg, but since B.J. needed time to go through Peg’s package, Hawkeye needed time to have read his magazine, leave the Swamp, get annoyed by the crowd, then come back to the Swamp “starved,” already aware that Peg had sent B.J. a cake in that package, it seems Klinger did not get the chance to eat his egg until lunch – perhaps that adds to his motivation to try to escape the Army so many times in the next couple of days. This places S4 after lunch but before 1330 hours. Why Hawkeye is starved after lunch is uncertain, though his frustration with the lack of sleep, lack of things to do, and the noisy crowd may have made him lose his appetite – though it becomes a trope in later seasons of M*A*S*H that they never got much good food at all (which is why Klinger makes such a big deal over a fresh egg).

Hawkeye’s nap must have helped his tiredness and frustration, since he is very enthusiastic for the jeep-stuffing in S5a. Scene 5a has to be the same day shortly after S4, since Hollister arrives at the conclusion of the photograph, and S4 is the same day as S3, when Mulcahy says Hollister is coming later that afternoon. It is likely after 1330 hours: even though Hawkeye had no interest in the cockroach time trials, he wouldn’t compete with that, especially to get so many people to squeeze into the jeep, and he needed time to get a camera and a crowd after his nap. Also, based on later information from season five’s opener “Bug Out,” B.J. has a vested interest in the 4077’s cockroach race system – potentially, his involvement with Blue Velvet, his racing cockroach, begins this episode, but it’s understandable he wouldn’t write that to his wife. Some might argue that because B.J. is not around when the jeep-stuffing camera shot occurs, it is happening the same time as the cockroach trials, but that is still unlikely for the reasons given above. When does the recounting of this story occur? Most likely in L2, with the majority of the Col. Hollister information, which B.J. has begun by the time of scene 7a. L1 seems to have been written during the Friday and Saturday of S2-5c; L2 the Sunday-Monday of S6-10.

S5b, the first of two mini-scenes of Colonel Potter confronting Klinger, clearly takes place concomitantly with the jeep scenes 5a and 5c. Season 4 of M*A*S*H uses a few tropes to help the audience acclimate to the major changes, as highlighted above. Various incidents of Col. Potter confronting Klinger over his attempts to escape from the army are one such trope, though it continues a tradition begun with Klinger and Henry Blake. That Col. Potter is ordering medical films with Col. Hollister’s arrival imminent leads one to suspect that only Mulcahy and B.J. know he is on his way. Additionally, Frank and Margaret do not object to Hawkeye’s jeep-stuffing on the grounds a VIP is coming – they, too, seem unaware of that. Knowing as the audience does how infatuated they are with big brass and VIPs, Margaret and Frank would have used that as a major argument (if you will pardon the Hawkeye-like expression). When Hollister arrives in S5c, Margaret recognizes him though she seems surprised he is there.

Based on the observation that the 4077 all go to a church service to support Father Mulcahy when he is being observed, it is possible to deduce that they would not hold cockroach time trial races (even the finals) when Hollister was there. Assuming, then, that the time trials occurred at its scheduled time of 1330 hours, it would not be possible for Mulcahy to go through a whole sermon and then spend time with Hollister before the 1400 hours mark in S7d; thus, the service Mulcahy conducts for everyone, most likely during a mid- to late morning (considering Radar still has fresh shaving nicks), in S6 takes place the day after S5a-c, most likely making it, appropriately, Sunday. Ironically, then, it wasn’t really B.J. who needed Mulcahy on Sunday, but Mulcahy who needed B.J. (and everyone else) to support him in front of Hollister, which they do (in a very over-the-top fashion). Considering this entire episode is a series of events B.J. relates to his wife Peggy (from various letters), one must ask how B.J. then knows about this post-service conversation between Hollister and Mulcahy. The best answer is that Mulcahy tells him after S1 ends, when B.J., Klinger, Radar, and Mulcahy are alone (with Kellye) in the Officer’s Club. Considering those three are in all the scenes in which B.J. is not (except for the first scene of Frank and Hawkeye teaching the Koreans English), clearly they tell B.J. about those episodes, either after Hawkeye makes his departure in S1 or some other time, though post-S1 is most likely.

Scenes 7a-7d must be later that morning or early afternoon, still most likely Sunday. Aside from the unfortunate fact that most visiting generals or VIPs to the 4077th either die or lose their rank and so Hollister is making a wise decision is leaving fairly soon, he has already spent most likely a day observing Mulcahy, so the time he spends “running [him] ragged” as B.J. calls it, is, ironically, on the Sabbath day, on which Frank and Margaret had to apologize to Hollister for working. The letter B.J. is now writing in the warm Sunday sun, observing Hollister and Mulcahy, is most likely L2. His attitude is different, the tone by which he writes is more upbeat, and the content is slightly different. He is reminded that Colonel Potter wanted to train Koreans to “work in the wards” so the “first step was to teach them English,” he tells Peg. The past tense “was” indicates that at the time B.J. writes this in S7a, not only the idea of teaching them English had occurred but also S7b, an evening time scene of Frank then Hawkeye trying to teach English to a handful of young Korean men. Frank, after a futile hour, finds some success teaching them Republican-sounding political cries; Hawkeye comes in and relieves Frank, though he quickly gives up the ward-related language in favor of verbal insults of Frank (most likely the “Frank Burns eats worms” expression is taught shortly after S7b ends). Because we only see the end of Frank’s time with the Koreans, most likely B.J. knows about it through Hawkeye, who tells him what he overheard Frank say and then what he “teaches” the Koreans. Remembering that the entire episode is predicated on what B.J. is writing Peggy, B.J. must have learned about the event himself, most likely from Hawkeye. When does S7b occur? Because the Koreans are in the night scene of S9c, the late night after the afternoon of S7a when B.J. is writing about it to Peg, S7b most likely happened quite recently, probably the night before, thus the Saturday night after S5c. If it was the night before, that could add to the supposition that B.J. is writing a new letter here in S7a. Since B.J. is wondering if he told Peg about the Koreans and doesn’t (or can’t) check back in the letter (which is something he immediately does in S7c), he is most likely telling her an event that occurred between the completion of L1 and the beginning of L2, its nearness in time suddenly coming back to his memory, unless he was prompted seeing Mulcahy and Hollister running around the compound, which would be an odd association.

S7c, back to B.J. in the warm Sunday afternoon sun, begins with B.J. reflecting that it has been two pages of L2 since he told Peggy how much he loved her. Why would two pages of telling his wife about Frank and Hawkeye teaching Koreans to speak English cause him to love Peg even more? Most likely it is because the teaching people to speak English reminds him of his daughter Erin, how he is looking forward to being with them again, teaching his daughter to speak and read, remembering how she is doing all of the rearing of their daughter alone, and thus leading him to love her even more. B.J. is, after all, predominantly the ideal family man character, in contrast to Trapper John.

S7d is predominately from Mulcahy’s perspective, again a scene he most likely related to B.J. after S1, when B.J. is eager to write something new to Peggy (thus he may have asked the other men in the Officers Club for details or perspectives on the recent days). In an episode built on letter writing, Mulcahy’s reticence to write a letter to Private Davis’s parents too soon is interesting. Adding to the multiple parallels, Hollister’s comments about “a strong, affirmative letter” being just what the Davis family needs is essentially what B.J. is doing with his letters to Peggy in order to keep his sanity, and Hawkeye and Mulcahy both play the part of the cynics who need to learn the lesson of positive thinking (adding to the great irony of the episode, considering they are usually the two characters who try to keep everyone else positive).

S8 is an anomaly, having no tangible connection to any other scene or event in the episode, other than its obvious parallel to S5b and S10. In S8, Klinger is captured once again by the MPs and brought into Potter’s office, this time with his bizarre inflatable raft plan. Klinger’s indifferent response to the havoc caused by his inflation of the raft, even knocking over his own commanding officer, may indicate his bitterness with the way Potter treated him the previous day in S5b (Klinger did storm out in S5b). His growing dissatisfaction and general tiredness demonstrated in S1 probably grew out of these two scenes and S10.

S9a takes place at 1800 hours, four hours after S7a-d, thus the same day since S6. Hollister’s final message is, in keeping with his character, “It’s your straggler who misses the Lord’s streetcar. ¡Vaya con Dios!” Mulcahy, keeping with his character, is not reassured by this, primarily because he is still nervous about Private Davis and his lack of desire to give false hope. Radar’s frantic message about Davis’s condition only appears to give credence to Mulcahy’s reticence. Klinger’s effort in S9b in getting Davis’s new x-ray belies his growing lackadaisical attitude to his role in the army. All sub-threads of the episode come together in S9b, as Mulcahy, Klinger, and the Korean ward people are all there to watch Hawkeye and B.J. fix what Frank refused to do in S2. S9c, later that night or early Monday morning, Mulcahy learns that B.J. and Hawk saved Davis’s life. This is another good scene about Mulcahy’s interesting behavior as a priest, though that will require a more specific examination at another time, considering it appears he doesn’t think of praying until hours into the operation. Mulcahy’s inspiration from Hollister in their private conversation at the end of S6 is incredibly short-lived, primarily because his own cautious nature overrides his temporary enthusiasm. Also, B.J.’s reaction to the Korean ward people saying “You tell ’em ferret face” indicates he knew about S7b prior to the occurrence of S9c.

The final scene, S10, opens with the sounds of Mulcahy playing the same song first heard in S1, though this scene takes place outside the Swamp, with B.J. and Hawk playing chess. It is another late morning or afternoon scene, most likely either the day that ends with S1 or a day or two before S1. B.J. is working on the end of L2. This is based on the fact Hawkeye is not mad that B.J. is writing this letter (though he is somewhat miffed at the third letter in S1). Again, B.J.’s language and tenses indicate the passage of time: “Things are pretty quiet right now,” he says to Peg, in preparation for S1. Private Davis pulled through (past tense), was shipped stateside (past tense), and Potter doubled the guard on Klinger who isn’t (present tense) giving him any trouble. Yet right after he writes that to Peg, Klinger is brought along by two MPs, disguised as a bush. This discredits B.J.’s statement and adds to everyone’s general downtrodden attitude in S1. Klinger’s reaction is the most angered of the three scenes of his escape attempts; by the end of the day, Klinger’s anger has dissipated to the quiet, mildly forlorn attitude of S1. Assuming that Mulcahy’s song can be heard because he is happy Davis pulled through (and is actually being played during this scene), S10 is the morning of S1, whether it is the day after S6-9 or multiple days later. The final capture of Klinger and the absence of anything going on (other than their chess game) wear on Hawkeye and B.J. until they are as despondent and tired as they are in S1. It is most likely afternoon, since Davis would have needed some time to pull through and get shipped out. That might require more time than just a morning, but they have shipped out patients with shorter turnaround time. Underscoring the general chronological disjuncture of the episode are the two chess moves B.J. and Hawkeye use in their game: B.J. opens with the 1910 Zuckertorts attack; Hawkeye follows it up with the 1906 Lapinsky move, an earlier move to counter a later move. As the episode closes, we have learned what brought the main characters to their states in S1, and that B.J.’s line “there’s just nothing to do when you’re not working” is, in fact, the last thing that happens in the episode chronologically. Here, then, is the episode in proposed chronological scene order:

S2: Friday morning, first operation on Private Davis

S3: Saturday morning, 0500 hours (L1)

S4: Saturday morning, c. 1200-1300 hours (L1)

S5a-c: Saturday afternoon, after 1330 hours, jeep scenes and Klinger’s 1st escape attempt

S7b: Saturday evening, training Koreans to speak English

S6: Sunday morning, Mulcahy’s service

S7a, c, d: Sunday afternoon, 1400 hours (L2)

S8: Sunday afternoon, c. 1400-1800 hours

S9a-b: Sunday afternoon: 1800 hours

S9c: Late Sunday night/early Monday morning

S10: Monday or Tuesday afternoon, chess game, depending on how long Davis took to recover (L2)

S1: Late Monday or Tuesday night (L3), with memories of (L1)

The theme of “Dear Peggy” is communication: B.J. writes three letters (of which we learn only parts); Col. Potter desires to train Koreans to speak English; Col. Hollister tells Mulcahy he is God’s “messenger” to these people at the 4077; Hollister convinces Father Mulcahy to write an affirmative letter (perhaps prematurely) to Private Davis’s parents; Klinger asks B.J. to interpret his dream for him; Radar brings news of Davis’s condition to Mulcahy and Hawkeye; Hawkeye tries to tell the world that the 4077th can break the world’s record for the number of people in an automobile at one time. Mulcahy learns that his lack of faith and reticence to communicate not only through prayer but also letter writing gave him nothing but unnecessary worry, so he is finally free to relax with happy music on the piano. Had he been God’s messenger like he should have, he would not have kept Hollister’s arrival a secret or hesitate to write Davis’s parents. Klinger learns (albeit temporarily) that his escape attempts are always futile, so he resigns himself to wearing a dress and hanging out in the Officers Club. Hawkeye doesn’t learn anything much, though he is reminded that momentary excitements such as stuffing more than thirty people into a jeep brings transitory happiness at best (in a way punished for trying to prevent B.J. from communicating – enjoining B.J. not to tell Peg about Klinger’s egg lest it get lost “in translation” and berating him for trying to keep his sanity by writing so many letters). B.J. learns the key lesson of the Korean War: there’s fundamentally nothing for a M*A*S*H doctor to do when he’s not working. The great irony of the episode (noted, as we’ve seen, laden with several ironies and parallelisms) is that it presents this theme of communication in the most structurally convoluted way any M*A*S*H episode presents its narrative: flashbacks within flashbacks, narrative imbrications, multiple letter writings, central character focus shifts, a non-linear narrative, a disjointed frame structure, and opening the episode with the chronologically last scene of the episode in a kind of inverse chiastic composition.

Even with all that confusion, “Dear Peggy” is a very enjoyable episode from one of the finest television series of all time. Season four does a remarkable job of adapting to the changes brought by actor departures and transforms the show from a generally light-hearted, hilarious, mildly risqué yet conventional program to a topical, narratively-diverse series. The complex narrative structure of “Dear Peggy,” once understood, only adds to the enjoyment and appreciation of this fine program. Finest kind, as Hawkeye says.